A 26-year-old woman with no relevant medical history consulted because the hair in some areas of her scalp had been gradually falling out for the previous 2 years and the rate of hair loss had increased in recent months. She was diagnosed with alopecia areata (AA). Treatment with mometasone and vitamins produced no improvement.

The patient had long, wavy hair, which she wore loose on the day she came to our clinic. For the previous 4 years, she had been using a tight elastic headband and styling gel because, as a cook, she was required to wear her hair up at work (Fig. 1).

Physical ExaminationPhysical examination revealed 2 symmetrical ovoid plaques of alopecia with diminished capillary density in the temporal regions, measuring 12×6cm and 10×8cm, with a positive hair-pull test at the borders and hair casts (Fig. 2). There was also a small, poorly defined frontal plaque with diminished capillary density, measuring 3×2cm. Trichoscopy revealed empty follicular orifices and areas without follicular orifices. Black dots, hyperkeratosis, and perifollicular erythema were not observed.

It was observed that the elastic headband causes traction in the areas in which alopecia was present.

Additional TestsBiochemistry profile, complete blood count, ferrokinetics, and thyroid-stimulating hormone were normal.

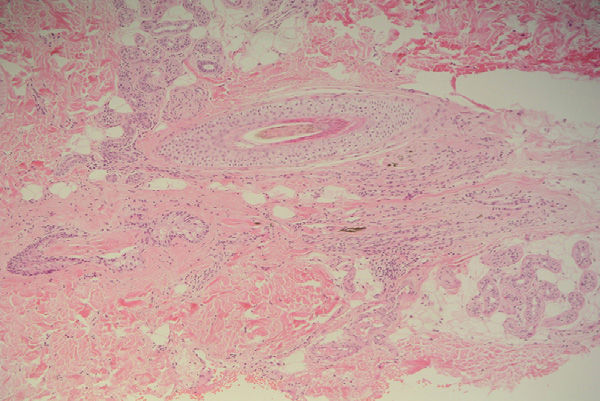

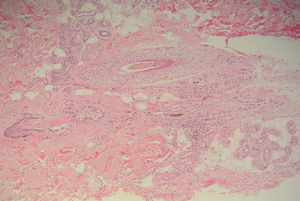

HistopathologyAnalysis of transversal and longitudinal sections revealed fibrous tracts of follicular regression with clumped melanin. Direct immunofluorescence was negative (Fig. 3).

What Is Your Diagnosis?

DiagnosisPartially scarring traction alopecia (TA) secondary to long-term use of an elastic headband during work.

Clinical CourseWe recommended that the patient stop using the headband and prescribed clobetasol and minoxidil. Repopulation was not initially achieved. However, 20 weeks after advising the patient to stop using the headband, partial repopulation of the 3 plaques—especially the frontal one—was observed, although patchy areas without follicular orifices persisted.

CommentTA is a mechanically induced type of alopecia. The most widely recognized cause of TA is prolonged and/or repeated tension on the hair over a long period of time, caused by various types of hairstyles—tight braids, ponytails, buns, extensions, and hair straightening—or by traumatic manipulation.

TA is characterized by elongated or linear plaques of alopecia, usually in the temporoparietal and/or frontal region of the scalp, the areas where tension is greatest.1–4

Hair casts observed by trichoscopy indicate active traction, but are not always present.4 No other specific trichoscopic signs are known. Trichomalacia and accumulations of pigment (incontinentia pigmenti) are suggestive, but not specific, histopathologic findings. Characteristically, the number of terminal hair follicles is reduced and no inflammatory infiltrate is present. In advanced stages, terminal hair follicles can be replaced by fibrosis.2

TA is relatively common in African American women, and very tight African-style braids (cornrows) are the most common cause of the condition.5 TA is rare in white women because of the different racial characteristics of their hair and, especially, because of their different hairstyling habits. In white women, TA is associated, very rarely, with wearing ponytails or tight buns regularly for years.1,4

If the hairstyle responsible for the condition is not evident at the time of consultation, the physician may erroneously diagnose AA because both conditions are characterized by similar plaques and because there are generally no clinical manifestations of inflammation.3,4 The differential diagnosis also includes lichen planopilaris and other mechanical alopecias (trichotillomania and friction alopecia).

TA can occur in 2 phases. In the initial phase, it can be reversed if the patient strictly avoids all traction and manipulation (the only effective treatment). If the cause persists, permanent follicular destruction occurs and the condition progresses to irreversible scarring alopecia, also known as end-stage TA or follicular degeneration syndrome.1–7

The time needed for scarring TA to develop is unknown. It is therefore essential to assess the possibility of TA in patients with temporoparietal or temporofrontal plaques of alopecia by asking the patient specifically about his or her hairstyling and manipulation habits.3,4

Occupational cases of TA caused by uniforms—such as nurses’ caps or nuns’ coifs—were more common years ago.1 Nowadays, the cause of TA is usually cosmetic, namely, traction-inducing hairstyles. The cause in our patient—the use of an elastic headband at work—suggests occupational TA.

Please cite this article as: Ézsöl-Lendvai Z, Iñiguez-de Onzoño L, Pérez-García L. Placas alopécicas en una cocinera. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:340–341.