Dermal melanocytosis includes a wide variety of congenital and acquired, histologically indistinguishable entities characterized by an intradermal proliferation of fusiform pigment-bearing melanocytes in the absence of melanophages.1,2 Clinically the lesions appear as brown or bluish macules, depending on whether the melanin pigment is located predominantly in the superficial or deep dermis. Congenital dermal melanocytosis includes Mongolian spots and nevi of Ota and of Ito. Nevus of Ota (nevus fusoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris) typically develops on the face in the area of distribution of the trigeminal nerve, whereas nevus of Ito (nevus fusoceruleus acromioclavicularis) affects the shoulder and neck region. These nevi, which are present at birth in around 60% of cases, rarely disappear in later years. Mongolian spots occur on the lower back or buttocks and are also usually present at birth, but generally regress in the first years of life.3

Acquired dermal melanocytoses are rare. Hori et al4 first described acquired bilateral Ota-like nevus in 1984. Although acquired melanocytoses tend to affect the face, they have also been reported on nonfacial sites (the upper and lower extremities, back, hands, and feet). Prevalence is highest among Asian women, and appearance in white individuals is very rare.5

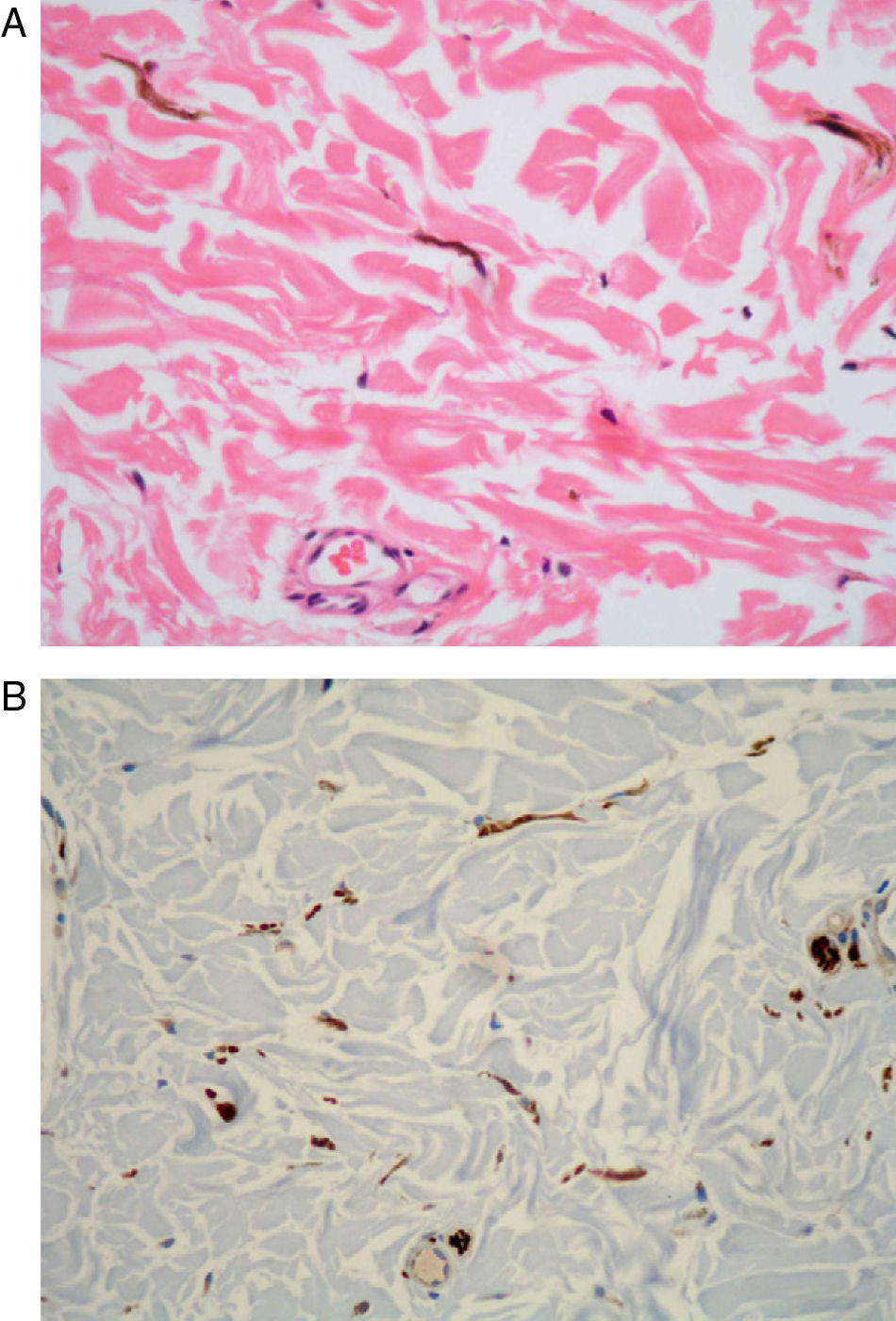

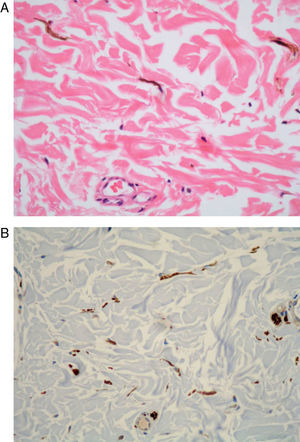

We describe the case of a 49-year-old woman with an 8-year history of an asymptomatic bluish-gray skin lesion, 25cm in diameter, located on the right side of the upper back (Fig. 1). The patient stated that she was taking no drugs and that she had not experienced any trauma or inflammatory disorders in the affected area. Two years before the consultation, she had undergone surgery for Astler-Coller stage B2 colorectal cancer. Two biopsies of the skin lesion were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for conventional histology study. Both samples revealed a proliferation of pigmented fusiform dermal melanocytes between collagen bands (Fig. 2A). Staining was positive for Melan-A, HMB-45 and S-100 (Fig. 2B). There was no evidence of an increase in epidermal melanocytes or of melanophages in the dermis. These histologic findings confirmed our clinical diagnosis of acquired dermal melanocytosis.

Nonfacial acquired dermal melanocytoses are very rare, particularly in white persons. There have been fewer than 30 cases reported, of which only 3 were in white individuals.6 The disorder predominantly affects middle-aged adults, typically Asian females. Malignant transformation of these lesions has occasionally been described.7

The pathogenesis of acquired dermal melanocytosis is uncertain. The existence of latent dermal melanocytes resulting from abnormal migration from the neural crest or from the hair bulbs or epidermis (a process known as “dropping off”) has been suggested as a possible cause.4,8,9 The dormant melanocytes may be reactivated by exogenous agents such as solar radiation, local inflammation, trauma, drugs, hormone therapy with estrogen or progesterone, or other, as yet undefined, stimuli. We could associate none of these factors with the development of the dermal melanocytosis in our patient. Colorectal cancer was the only relevant element in the patient's personal history. Dermal melanocytosis associated with malignancy has only been described in 2 cases of bladder cancer.8,10

We are of the opinion that the dermal melanocytosis in our patient was not linked to the adenocarcinoma, as the skin lesion was present many years before the cancer was excised. The data at our disposal are insufficient, in any case, to establish a clear link between dermal melanocytosis and visceral malignancies.

Please cite this article as: Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Melanocitosis dérmica adquirida extrafacial. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2011;102:556-57.