Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer in humans and its incidence is both underestimated and on the rise. cSCC is referred to in the literature as high-risk cSCC, locally advanced cSCC, metastatic cSCC, advanced cSCC, and aggressive cSCC. These terms can give rise to confusion and are not always well defined. In this review, we aim to clarify the concepts underlying these terms with a view to standardizing the description of this tumor, something we believe is necessary in light of the new drugs that have been approved or are in development for cSCC.

El carcinoma epidermoide cutáneo (CEC) es el segundo tumor más frecuente en humanos y tiene una incidencia creciente e infraestimada. En la literatura nos encontramos con términos como CEC de alto riesgo, CEC localmente avanzado, CEC metastásico, CEC avanzado y CEC agresivo, que pueden dar lugar a confusión y que en algunas ocasiones no se encuentran del todo bien definidos. En esta revisión pretendemos aclarar estos conceptos con la idea de lograr homogeneidad en su descripción, algo que parece necesario a la luz de los nuevos fármacos aprobados y en desarrollo para este tumor.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer and its incidence is underestimated and increasing.1,2 The number of cases of cSCC has increased between 50% and 300% over the last 30 years,3 and in 2030 its incidence is projected to double in European countries.4 Whether this increase is real or corresponds to early detection of the disease is subject of debate.5 The increased incidence is, nevertheless still apparent in studies that exclude cases of in situ cSCC.6 While recognizing that data on the cSCC incidence may be unreliable, it is estimated that the risk of developing cSCC at some point in an individual's life lies between 7% and 11% in the Caucasian population7 (between 9% and 14% in men and 4% and 9% in women).8 In Spain, studies that analyze raw incidence rates estimate values of 38.16 cases per 100 000 inhabitants per year,9 although there are no registries that allow a true estimate. The incidence is somewhat greater than that reported in other European countries (see review by Lomas et al.1)

Ten years after surgery for cSCC, survival is greater than 90%, the rate of lymph node metastasis is around 4%, and mortality is around 2%, although the tumor is an important public health problem responsible for a large number of deaths given its high incidence.10 In fact, cSCC is the second most frequent cause of death due to skin cancer after melanoma and is responsible for most deaths due to skin cancer in indivduals aged over 85 years.3 In some areas of the United States, mortality rates are comparable with renal carcinoma, oropharyngeal carcinoma, or melanoma.3

In recent years, several authors have focused their research on analyzing factors associated with worse prognosis in cSCC. The literature refers to terms such as high-risk cSCC, locally advanced cSCC, metastatic SCC, advanced cSCC, and aggressive SCC. These terms can give rise to confusion and are not always well defined. This review aims to clarify these concepts and thus standardize description of this tumor, something we believe is necessary in light of new drugs already approved and those in clinical development.

Prognostic Factors in Cutaneous Squamous Cell CarcinomaClinical Prognostic FactorsTumor-Related FactorsThe horizontal spread of the primary tumor is a well-known prognostic factors in cSCC.11–22 A diameter greater than 2cm has been associated with a 3-fold greater risk of recurrence and 6-fold greater risk of metastasis.22 The most specific cutoff for determining high risk associated with tumor size has been set at 4cm.23

Certain sites are associated with worse prognosis in cSCC.3,11,13,15,16,19,24–30 Traditionally, the outer ear and lower lip have been considered sites of high risk, with a 2-fold increase in the risk of metastasis,12,15 and in one systematic review, the temples were associated with an even greater risk of recurrence and metastasis. The vermilion border of the lower lip is associated with a 5-fold greater incidence of lymph node metastases compared with involvement of the skin of the lip alone; cSCC located on the cutaneous part of the lip have lymph node involvement rates similar to those of other areas.31 The risk of lymph node spread is not as high in the nose or internal canthus of the eye, although local progression is an important problem in these areas.

Recurrence of the primary tumor has been associated with a greater risk of lymph node metastasis.12,13,24 In addition, recurrent cSCC appears to be more aggressive than primary cSCC and has been associated with a larger tumor size and greater risk of perineural and lymphovascular invasion, as well as invasion of subcutaneous cell tissue.14 Presence of involved borders after the initial excision is also considered a risk factor (recurrence in 50% of cases).

Clinical evidence suggests that rapid growth rate (GR) is an important risk factor for cSCC and this is reflected in the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.32 An old study had already found an association between rapidly-growing tumors and worse prognosis.33 More recently, it has been observed that GR>4mm/month in the long axis of the tumor is associated with worse disease prognosis and a greater risk of lymph node metastasis.34

Finally, the association of neurologic symptoms with cSCC is a clinical marker of poor prognosis that is usually associated with presence of perineural invasion (PNI) (see Histopathologic Prognostic Factors below). Symptoms associated with PNI in cSCC include above all pain and paresthesia, although itching, stinging, and, more rarely, motor nerve paralysis may be present.32,35 Moreover, pain seems to be a key symptom in the identification of cSCC in solid organ transplant recipients.36

Patient-Related FactorsImmunosuppression is a risk factor for the development of cSCC. cSCC is particularly common in solid organ transplant recipients, most frequently affecting those who have undergone heart transplantation. This group of patients is followed by recipients of lung, kidney, and liver transplants37; those with hematological malignancies, particularly chronic lymphatic leukemia and small cell lymphocytic lymphoma38; those receiving chronic immunosuppressant treatment, particularly cyclosporin39 and azathioprine40—especially after exposure to UV radiation40,41; and those positive for HIV.42 The cumulative incidence of cSCC increases progressively with duration of immunosuppression,43,44 and, in general the tumor is more aggressive in immunosuppressed patients.15,42,45–47

Worse prognosis has been demonstrated in cSCC that develops on long-standing scars, particularly those caused by burns48,49 and on previously irradiated skin.50,51 cSCC is also more aggressive in some genodermatoses, particularly bullous epidermolysis, where it is the leading cause of death.52 cSCC is more frequent in other hereditary diseases, such as xeroderma pigmentosum,53,54 oculocutaneous albinism,55,56 congenital dyskeratosis, Bloom syndrome,57 Rothmund-Thomson syndrome,58,59 Werner syndrome,60 keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness syndrome,61,62 Ferguson-Smith syndrome,63,64 Muir-Torre syndrome,65 and Lewandosky-Lutz syndrome,66 among others. Although there is no information to support the affirmation that cSCC is more aggressive in all these diseases, and indeed in some of them the tumor tends to show a reasonably good prognosis, the high risk requires strict management protocols in these patients.67,68

Histopathological Prognostic FactorsThickness has been related to prognosis of cSCC in several studies,11,12,14–17,21,22,25,69–72 and it has even been identified as the most important predictive factor for metastasis.16 The probability of metastasis is almost nonexistent if the thickness of the tumor is less than 2mm, approximately 6% in tumors of 2 to 6mm, and 16% in those more than 6mm thick.16 Thickness should be measured from the stratum granulosum of normal skin adjacent to the tumor to the last invasive cell.23 This approach may be difficult when measuring thickness of exophytic lesions.

Tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat is another prognostic factor that has received attention in recent years.10,17,18 Presence of such invasion has been associated with a 7-fold greater risk of recurrence and an 11-fold greater risk of metastasis.22 Assessment of invasion beyond fatty tissue may, however, be more useful compared with tumor depth in some aspects. On one hand, it is useful in Mohs micrographic surgery, which assesses horizontal cuts in the surgical piece, in which the tumor thickness in millimeters cannot be assessed. In addition, the difficulties associated with assessing tumor depth in exophytic lesions are obviated and, furthermore, this assessment can justify the poor prognosis in some lesions that invade muscle despite having a moderate thickness.

Poor differentiation has been associated with poor prognosis of cSCC in several studies.11,16,17,19–22,25–27,69–79 According to published series, between 8%76 and 25%16 of cSCC are poorly differentiated. Differentiation has been associated with a 3-fold greater risk of local recurrence and a 5-fold greater risk of metastasis,22 as well as earlier recurrence.

PNI is present in 2.5% to 10% of cSCC and is associated with other histopathological features of poor prognosis.14 Studies have consistently recognized its implication in poor prognosis and it has been associated with a 4-fold greater risk of recurrence and a 5-fold greater risk of metastasis.22 More recently, it has been established that PNI should be considered as high risk when nerves with a caliber ≥0.1mm are involved.10,17,18 Moreover, PNI of deep nerves (located below the dermis) and extensive PNI are considered PNI features also associated with poor prognosis.80 It is necessary to differentiate between PNI and perineural dissemination. The former corresponds to histological detection whereas the second, by definition, is a more advanced stage that can be detected clinically and radiologically and is the pathway for invasion of the central nervous system by the tumor.81

Other histopathological risk factors in cSCC are lymphovascular invasion,25 infiltrative growth pattern,82 desmoplasia,16,83,84 defined as least 30% of the desmoplastic stroma associated with the tumor, and budding,85,86 defined by the presence of nests of 4–5 cells at the invasive front, although a clear consensus is lacking on this point.87 In addition, worse prognosis has been associated with certain histopathological variants of cSCC, particularly acantholytic cSCC,88,89 and adenosquamous cSCC,90 although recent series seem to suggest that the prognostic relevance of these features could be limited.91 The presence of an eosinophil-rich infiltrate and plasma cells has also been assessed,26 but more studies are needed to characterize inflammatory infiltrate associated with cSCC and relate the findings more reliably to prognosis. Some markers, such as EGFR,92,93 D2-40,94,95 and epithelial to mesenchymal transition markers96 have been associated with unfavorable prognosis in cSCC. Recently, expression of PD-L197–99 has been linked to a higher risk of lymph node metastases.

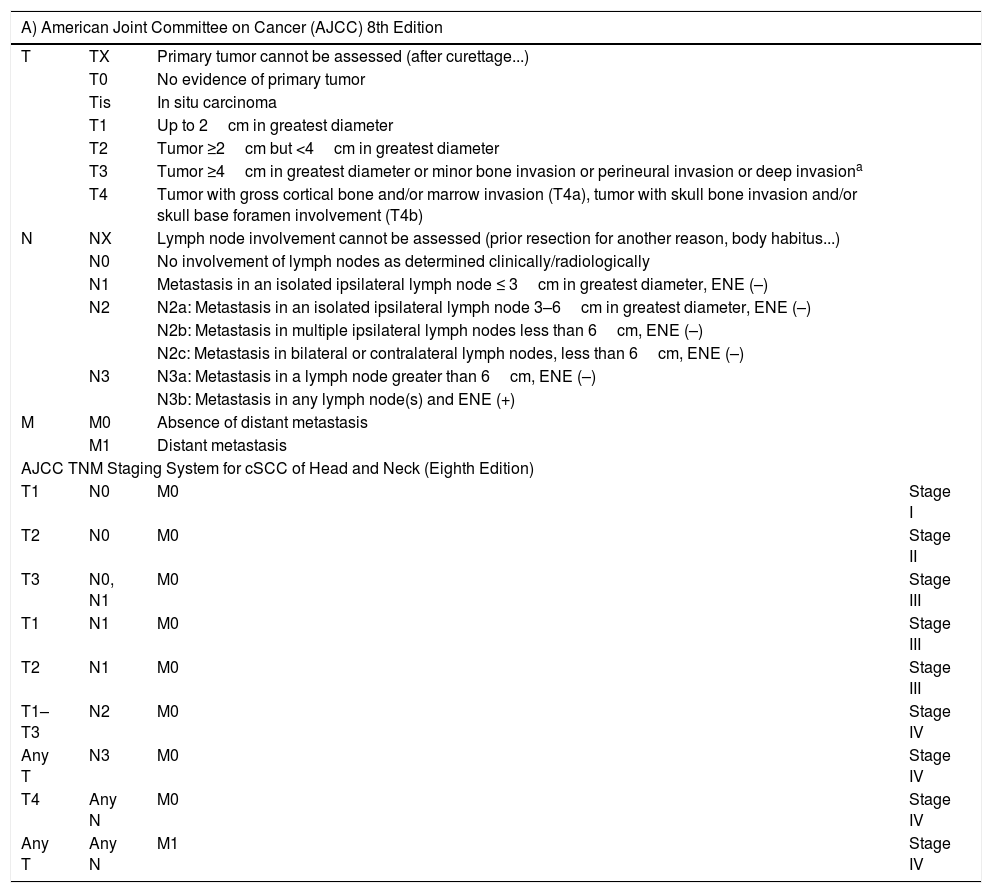

The staging systems use a combination of risk factors to define the different risk groups in. For cSCC, the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system and the alternative system of the Brigham and Women's Hospital are used. The characteristics of these systems are shown in Table 1.

Staging of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

| A) American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th Edition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| T | TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed (after curettage...) | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis | In situ carcinoma | ||

| T1 | Up to 2cm in greatest diameter | ||

| T2 | Tumor ≥2cm but <4cm in greatest diameter | ||

| T3 | Tumor ≥4cm in greatest diameter or minor bone invasion or perineural invasion or deep invasiona | ||

| T4 | Tumor with gross cortical bone and/or marrow invasion (T4a), tumor with skull bone invasion and/or skull base foramen involvement (T4b) | ||

| N | NX | Lymph node involvement cannot be assessed (prior resection for another reason, body habitus...) | |

| N0 | No involvement of lymph nodes as determined clinically/radiologically | ||

| N1 | Metastasis in an isolated ipsilateral lymph node ≤ 3cm in greatest diameter, ENE (–) | ||

| N2 | N2a: Metastasis in an isolated ipsilateral lymph node 3–6cm in greatest diameter, ENE (–) | ||

| N2b: Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes less than 6cm, ENE (–) | |||

| N2c: Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, less than 6cm, ENE (–) | |||

| N3 | N3a: Metastasis in a lymph node greater than 6cm, ENE (–) | ||

| N3b: Metastasis in any lymph node(s) and ENE (+) | |||

| M | M0 | Absence of distant metastasis | |

| M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

| AJCC TNM Staging System for cSCC of Head and Neck (Eighth Edition) | |||

| T1 | N0 | M0 | Stage I |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | Stage II |

| T3 | N0, N1 | M0 | Stage III |

| T1 | N1 | M0 | Stage III |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | Stage III |

| T1–T3 | N2 | M0 | Stage IV |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | Stage IV |

| T4 | Any N | M0 | Stage IV |

| Any T | Any N | M1 | Stage IV |

| B) Brigham and Women's Hospital Alternative Staging System | |

|---|---|

| T1 | 0 high-risk factors |

| T2a | 1 high-risk factor |

| T2b | 2–3 high-risk factors |

| T3 | 4 or more high-risk factors/bone invasion |

| High-risk factors for BWH staging system | |

| Diameter of 2cm or more | |

| Poor degree of differentiation | |

| Perineural invasion of nerves ≥0.1mm in caliber | |

| Tumor invasion beyond subcutaneous fat (excluding bone invasion, which upgrades tumor to BWH stage T3) | |

A) AJCC 8th Edition: includes site on lower lip; excludes eyelid carcinoma. Tumors of the vulva, penis, perineal region, and other sites other than the head and neck are excluded. ENE (extranodal or extracapsular extension) defined as extension through the lymph node capsule into adjacent connective tissue, with or without stromal response. B) Brigham and Women's Hospital Alternative Staging System.

Deep invasion defined as thickness greater than 6mm or invasion beyond subcutaneous fat. For a tumor to be T3, perineural invasion should be in nerves greater than 0.1mm in caliber, nerves beyond the dermis, or clinical and radiological involvement of nerves should be present without involvement or invasion of the base of the cranium.

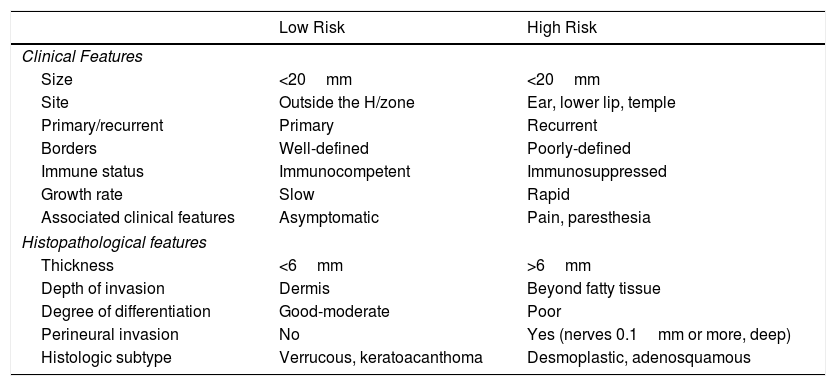

In practical terms, the presence of one of the factors of poor prognosis is what defines a cSCC as being of high risk (Table 2). However, the prognostic relevance of each factor is not the same and the combination of several is known to confer a greater risk than the presence of each by itself.18,100–102 Thus, a better definition of high-risk cSCC would require a better understanding of the prognostic relevance of each of the risk factors on one hand and their combination on the other. According to the current staging system23 and the alternative BWH system,100 high-risk cSCC would be considered as T3/T4 tumors as per the AJJCC-8 system or T2b/T3 as per the alternative BWH staging system. However, many tumors staged according to these systems are not going to be particularly aggressive.

Prognostic Factors in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC): Low-Risk and High-Risk cSCC.

| Low Risk | High Risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Features | ||

| Size | <20mm | <20mm |

| Site | Outside the H/zone | Ear, lower lip, temple |

| Primary/recurrent | Primary | Recurrent |

| Borders | Well-defined | Poorly-defined |

| Immune status | Immunocompetent | Immunosuppressed |

| Growth rate | Slow | Rapid |

| Associated clinical features | Asymptomatic | Pain, paresthesia |

| Histopathological features | ||

| Thickness | <6mm | >6mm |

| Depth of invasion | Dermis | Beyond fatty tissue |

| Degree of differentiation | Good-moderate | Poor |

| Perineural invasion | No | Yes (nerves 0.1mm or more, deep) |

| Histologic subtype | Verrucous, keratoacanthoma | Desmoplastic, adenosquamous |

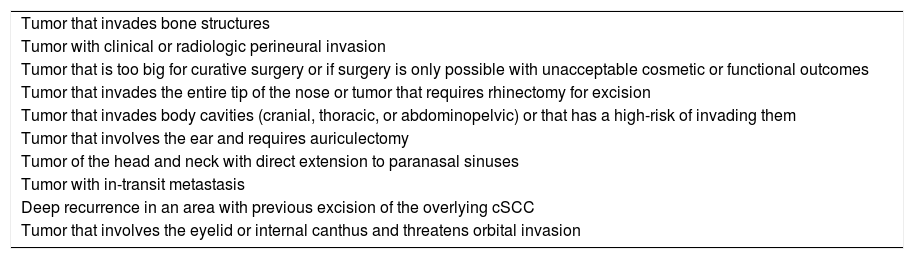

There is no standard definition of locally advanced cSCC, although all definitions do have points in common. These tumors have been defined as those not potentially curable or that are unlikely to be cured with surgery, radiotherapy, or combination treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) after consultation in a multidisciplinary committee.103 This definition is routed in clinical practice and has also been taken as a reference in some clinical trials in other types of nonmelanoma skin cancer, specifically basal cell carcinoma.104

The criteria for considering cSCC as locally advanced in a trial of the anti-PD1 drug recently approved for cSCC was that patients were not candidates for surgery for the following reasons: recurrence after 2 or more surgical procedures and curative resection was considered unlikely or because surgical treatment would lead to substantial complications or deformity.105 It is more difficult in theory to define which patients with cSCC cannot be considered candidates for conventional treatment. Those cases with extensive bone involvement, in view of the availability of new drugs, could be considered to benefit. Table 3 shows some clinical scenarios that would allow classification of cSCC as locally advanced.

Clinical Scenarios That Allow Classification of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma as Locally Advanced.

| Tumor that invades bone structures |

| Tumor with clinical or radiologic perineural invasion |

| Tumor that is too big for curative surgery or if surgery is only possible with unacceptable cosmetic or functional outcomes |

| Tumor that invades the entire tip of the nose or tumor that requires rhinectomy for excision |

| Tumor that invades body cavities (cranial, thoracic, or abdominopelvic) or that has a high-risk of invading them |

| Tumor that involves the ear and requires auriculectomy |

| Tumor of the head and neck with direct extension to paranasal sinuses |

| Tumor with in-transit metastasis |

| Deep recurrence in an area with previous excision of the overlying cSCC |

| Tumor that involves the eyelid or internal canthus and threatens orbital invasion |

Metastatic cSCC is defined as cSCC that has spread from its primary site in the skin. In most cases, metastasis is to lymph nodes or the parotid gland, and to a lesser extent to other organs. In transit involvement in the skin in cSCC, defined as a presence of foci of tumors differentiated from the primary tumor and before the first draining lymph node,106 could be considered a form of locoregional metastatic cSCC, by analogy with melanoma, although no change to the N category occurs in staging of the cSCC.107

Approximately 5% of cSCC are thought to progress to metastasis,108 although to date no exhaustive registers have been available to derive a true estimate. In 2013, in England, the automated registries included cSCC and metastatic cSCC, thereby enabling study of data at the population level for the first time.109 During 15.5 months of follow-up, 2.1% of the patients with cSCC developed metastatic disease,109 although the authors considered that the rate could be an underestimate given that International Classification of Diseases, 10th version, did not include specific codes for metastatic cSCC. Of these metastatic cSCC, metastasis occurred within 3 years of diagnosis of the primary tumor in 90% of cases.109

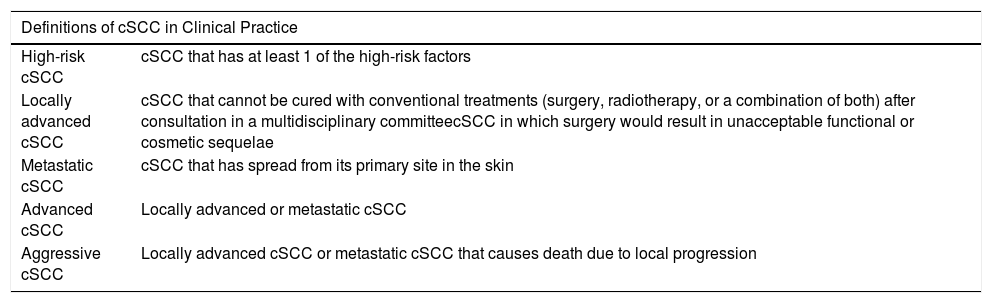

Advanced cSCC and Aggressive cSCCIn practice, the terms advanced cSCC and aggressive cSCC have been used to refer to more general clinical situations. Thus, the term advanced cSCC has been used to group locally advanced cSCC and metastatic cSCC.105 The term aggressive cSCC, in contrast, has been used to refer to metastatic cSCC and cSCC that leads to death due to local progression.45 The terms advanced and aggressive, however, may be nonspecific and, therefore, when they are used, it is appropriate to define the clinical context to which they refer. The following terms are related to poor prognosis in cSCC: aggressive cSCC, locally advanced cSCC, metastatic cSCC, advanced cSCC, and aggressive cSCC (Table 4).

Definitions of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC) With Poor Prognosis in Clinical Practice.

| Definitions of cSCC in Clinical Practice | |

|---|---|

| High-risk cSCC | cSCC that has at least 1 of the high-risk factors |

| Locally advanced cSCC | cSCC that cannot be cured with conventional treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, or a combination of both) after consultation in a multidisciplinary committeecSCC in which surgery would result in unacceptable functional or cosmetic sequelae |

| Metastatic cSCC | cSCC that has spread from its primary site in the skin |

| Advanced cSCC | Locally advanced or metastatic cSCC |

| Aggressive cSCC | Locally advanced cSCC or metastatic cSCC that causes death due to local progression |

Conventional surgery is the treatment of choice for most cases of cSCC, with differences in the margin depending on whether the tumor is low-risk cSCC (4mm) or aggressive cSCC (10mm).110 Mohs surgery is reserved for recurrent cases and for high-risk sites in which the safety margins might lead to significant functional compromise or unacceptable cosmetic outcomes. Adjuvant radiotherapy of the primary tumor is reserved for cases with PNI, particularly clinical, radiographic, extensive, involvement of nerves with caliber 0.1mm or more, of deep nerves, and for cases with positive margins that cannot be operated again safely to leave the patient tumor free.80 In inoperable patients, elective radiotherapy and both destructive and intralesional treatment can be an option.32,110 The usefulness of selective lymph node biopsy has yet to be established, although it might be beneficial in certain patient groups.111

Management of locally advanced cSCC is complex. In general, surgery by itself is insufficient or is inappropriate given the cosmetic and functional repercussions. New anti-PD1 drugs are now available and cemiplimab has been approved for the treatment of locally advanced cSCC105; this drug may be considered the option of choice provided the patient has an acceptable performance status at baseline. If the systemic option is not possible given the circumstances of the patient, palliative treatment can be considered. It is not clear whether systemic treatment is beneficial for reducing tumor mass and enabling surgical treatment with fewer sequelae for the patient (neoadjuvant setting).

In the case of metastatic cSCC, surgery is recommended whenever possible, followed by complementary radiotherapy.80,112,113 In inoperable cases, if the patient has a good performance status, systemic treatment, currently with anti-PD1 agents, is the preferred option. Despite the age of the affected population, a significant proportion of patients with advanced cSCC have a clinical situation that allows systemic treatment.103 Cemiplimab is the only agent approved for the treatment of metastatic cSCC and locally advanced cSCC.105 In patients with inadequate performance status and inoperable patients who are not candidates for or who do not respond to systemic treatment, palliative treatment is an option to be considered. Given that management of metastatic cSCC and locally advanced cSCC is fairly similar, the term advanced cSCC can be used to refer to those clinical scenarios.

ConclusionCurrently, there is no consensus definition for locally advanced cSCC and, given the imminent arrival of new drugs, such a consensus would seem necessary. The working group has concluded that locally advanced cSCC could be considered a tumor that cannot be cured with conventional treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, or a combination of both) after consultation in a multidisciplinary committee or cSCC in which surgery would involve functional sequelae or unacceptable cosmetic outcomes. Metastatic cSCC is defined as cSCC that has spread from its primary site in the skin. Advanced cSCC includes cases of locally advanced cSCC and metastatic cSCC, while cases of metastatic cSCC and locally advanced cSCC that cause death due to local progression (which could be considered cSCC that gives rise to major events) can both be termed aggressive cSCC. High risk cSCC is cSCC that has high-risk clinical or histopathological features, although this definition may be too broad given that it groups tumors that probably would not lead to unfavorable outcomes, and so better staging of these tumors will be needed in the future.

FundingJ.C. was partially funded for the projects: PI18/000587 (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, cofunded by FEDER grants) and GRS 1835/A/18 (Regional Health Service of Castille and Leon).

Conflicts of InterestThe authors have received honoraria as members of an Advisory Board for Sanofi.

Please cite this article as: Cañueto J, Tejera-Vaquerizo A, Redondo P, Botella-Estrada R, Puig S, Sanmartin O. Revisión de los términos que definen un carcinoma epidermoide cutáneo asociado a mal pronóstico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:281–290.