Sirsasana is one of the most common inversion postures in yoga and is proposed to increase blood flow to the brain, improving memory and other intellectual functions.1,2 When practicing this posture the body weight rests on the central-parietal region of the cranium. Beginners should maintain this posture for 1min, subsequently increasing to 5min. The posture should be performed under the supervision of an instructor to avoid injury.2

We describe a reactive skin injury caused by long-term practice of Sirsasana.

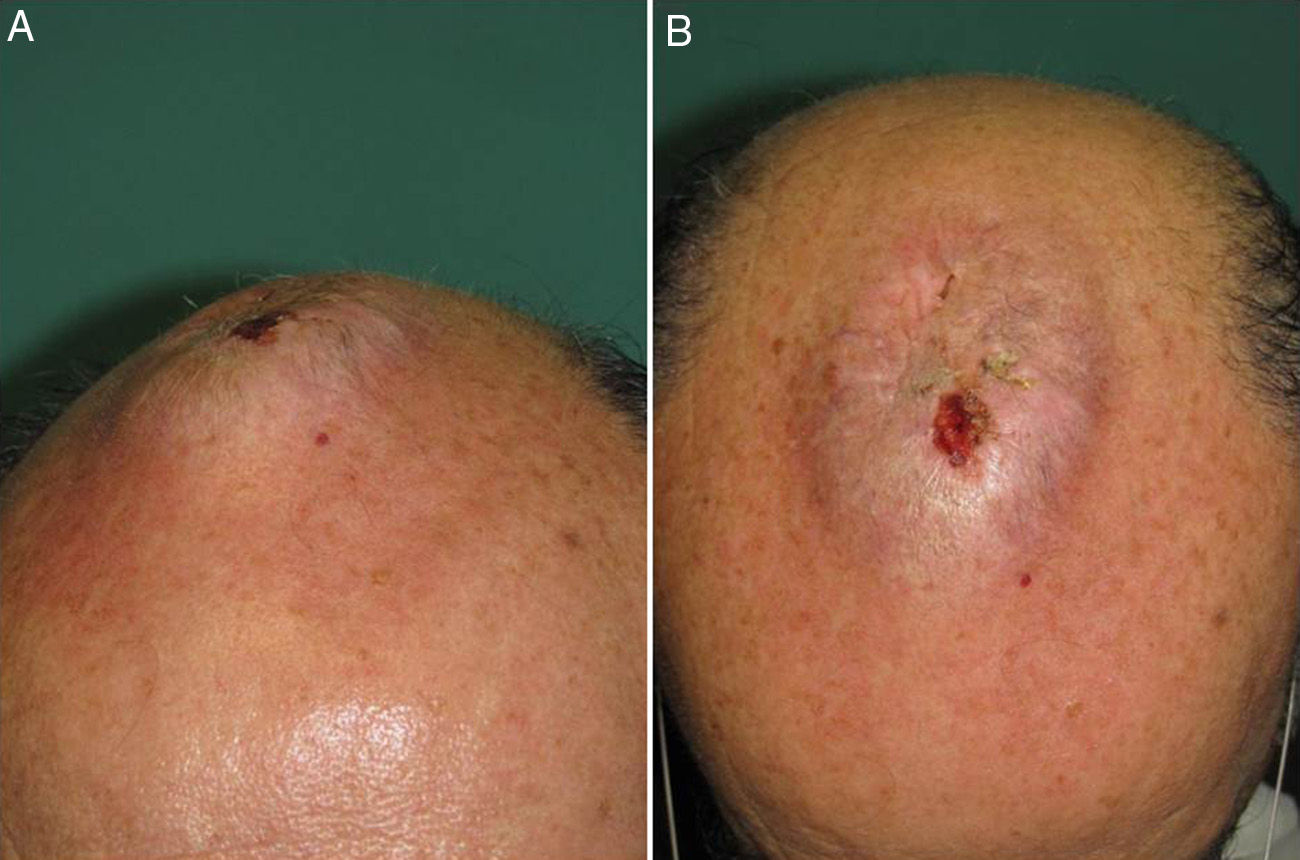

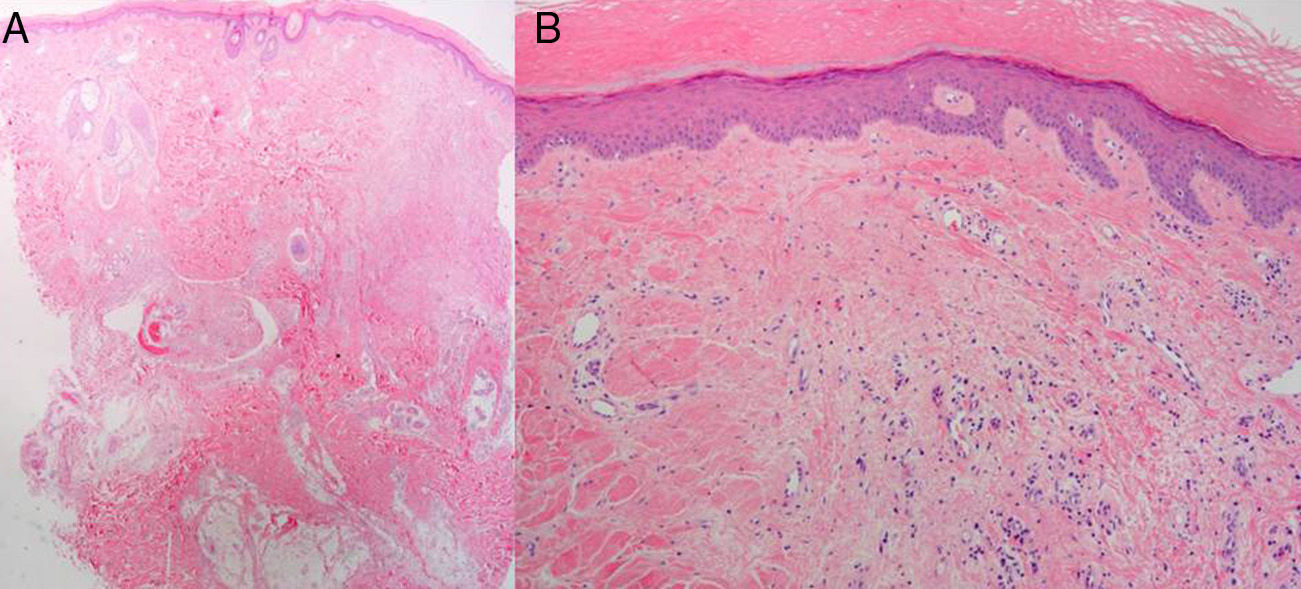

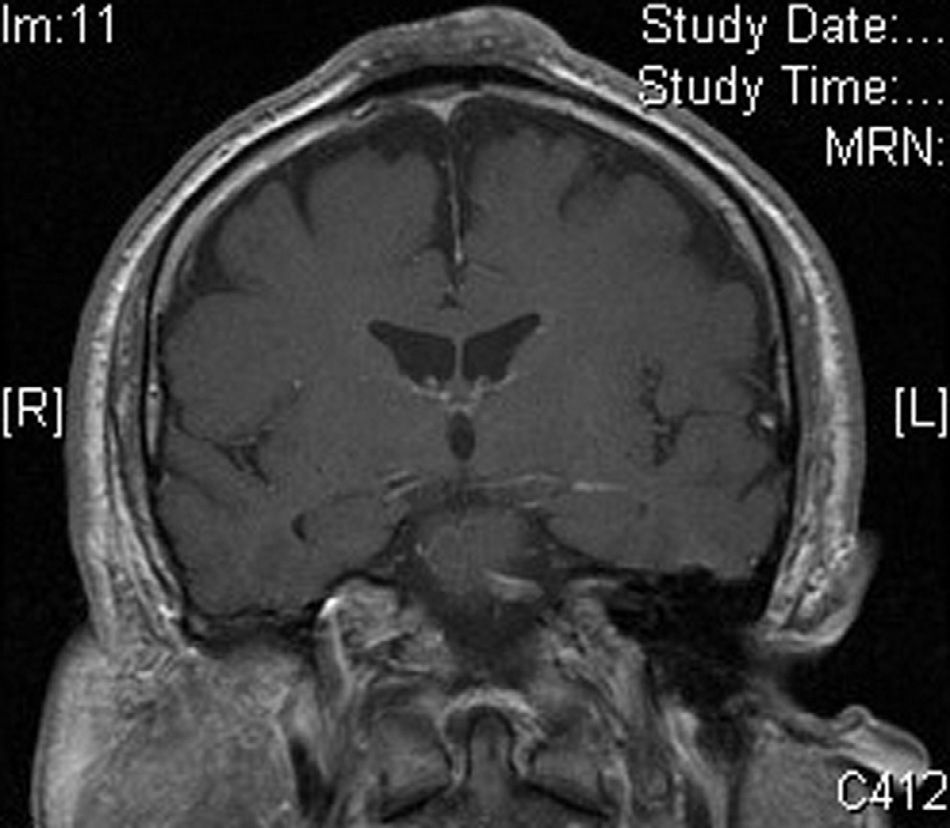

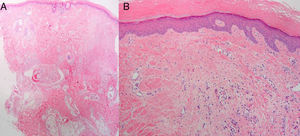

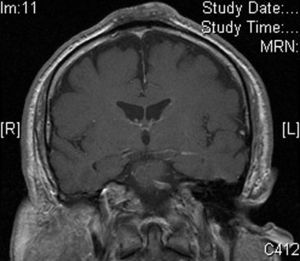

The patient was a 62 year-old man with no relevant past medical history other than the practice of an inverted yoga posture for 30minutes several times a day since the age of 15. He presented with a persistent, asymptomatic, raised lesion in the interparietal region that had appeared more than 20 years previously. The size of the lesion had increased during the first few years and then subsequently stabilized. Occasional ulceration and infection of the lesion resolved spontaneously or after antibiotic treatment for approximately 10 days. Physical examination revealed a hard, oval-shaped, tuberous lesion in the interparietal region of about 10cm in anteroposterior length and 6cm in width with a centrally eroded surface (Fig. 1,A and B). Blood tests revealed no significant abnormalities. Radiograph of the skull showed an increase in soft tissue in the parietal region and associated periosteal reaction. Based on these findings, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the brain was performed, revealing an extracranial soft-tissue mass in the upper frontal convexity along the midline, with discrete underlying periosteal reaction and no clear involvement of the outer table of the diploe, consistent with a reactive process. Skin biopsy showed marked orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild epidermal acanthosis. The dermis showed focal fibrosis with proliferation of small vessels, dense perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, and isolated siderophages (Fig. 2,A and B). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed thickening of extracranial soft tissue at the level of the coronal and sagittal sutures and the external table. The latter showed hypointensity in all sequences indicating sclerotic bone reaction. These findings were consistent with fibrotic changes affecting the extracranial soft tissues and sclerotic bone reaction in the underlying cortical bone (Fig. 3).

A, Biopsy of the parietal region of the scalp (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×2; panoramic image) B, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×4. Histopathological findings: marked orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild acanthosis; focal dermal fibrosis with proliferation of small vessels and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates.

The patient continues to practice yoga at the same frequency and intensity, despite being warned of the probable link between that activity and the lesion.

The lesion remains stationary after 24 months of follow-up.

In the diagnosis of frequently ulcerous, tuberous lesions of the cranium, the first step is to rule out soft-tissue tumor. The majority of soft-tissue tumors present clinically as deep, slow growing masses, and the differential diagnosis is established based on histopathology.3 Imaging tests allow for better delineation of the lesion and help to determine its relationship with adjacent structures, and thus should be performed before conducting histological studies.4 Once a tumoral origin is ruled out, various reactive lesions should be considered, particularly nodular fasciitis5 and cranial fascitis.6 Both are benign fibroblastic proliferations of unknown etiology, sometimes associated with previous trauma.7 These lesions present clinically as firm, well-defined masses that initially grow rapidly and then stabilize,7 as seen in our patient. Both forms of fasciitis share similar histological features, with loose, disorganized bundles formed by the proliferation of large spindle cells, myofibroblastic differentiation, no pleomorphism, and abundant non-atypical mitoses.5,7 In our case the biopsy ruled out fasciitis, leading to a diagnosis of reactive lesion secondary to long-term practice of Sirsasana. We believe that the development of this lesion was mainly due to the dedication of our patient to his exercises, which considerably exceeded the recommended daily duration.

Although yoga exercises are usually safe and promote health, some risks are associated with certain poses, such as inverted postures.1 From the dermatological point of view we have not found an association between skin lesions and the practice of yoga. However, some problems have been described in connection with the practice of Sirsasana. For example, intraocular pressure can be increased in healthy individuals, an effect that is reversed after cessation of the inverted posture (this increase may be more pronounced in people with glaucoma or optic neuropathy secondary to glaucoma,8 and may be associated with the progression of glaucoma9). Moreover, the central retinal vein can become occluded due to vascular thrombosis caused by an intermittent increase in conjunctival venous pressure and a decrease in venous drainage.2 Finally, cervical compressive myelopathy and cervical listhesis can be caused by the biomechanical alterations induced by the inverted posture.10

Given the steady increase in the number of people practicing yoga daily, we believe that the dermatologist should be aware of the possible complications associated with this practice and should be alert to associated skin problems that may occur.

Please cite this article as: García-Martín P, Llamas-Velasco M, Fraga J, García-Diez A. Lesión tuberosa parietal secundaria a Sirsasana, una postura de yoga invertida. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:724–726.