Medical professional liability is defined as the obligation of physicians to provide satisfactory reparations for the consequences of voluntary and even involuntary actions, omissions, and errors, within certain limits, committed in the exercise of their profession.1

Patient rights unquestionably include the right to make a claim if a patient has suffered damages. This situation can give rise to a number of administrative and legal complications of which we should be aware.

The first thing to do is to determine what is meant by damage and when this damage is deemed to be as a result of medical action. Damage or injury may be physical or psychological and liability may lie with any health care professional. The most common cases tend to be the following: an incorrect diagnosis and, therefore, incorrect treatment; inadequate follow-up of the patient after an intervention; premature or late medical discharge; insufficient importance placed on a patient's symptoms with failure to admit the patient; leaving surgical material inside a patient.

Within the spectrum of culpability, we should distinguish between malicious intent and negligence.2 A person acts with direct first-degree malicious intent when they are aware that they are acting, know that the action is illegal and will cause the result in question, and directly pursue that result. For example, a physician, out of enmity, decides, in the exercise of his or her functions, to take advantage of the fact that a patient is anesthetized to damage their spinal cord in order to leave them paralyzed. Direct second-degree malicious intent (sometimes called indirect malicious intent) is when the subject does not pursue the result, but does pursue the means that will inexorably produce said result. For example, a physician wants a patient not to be able to attend an event because they may be a potential competitor of the physician's friend. The physician decides to cause injury to the patient or aggravate their condition so that they spend more time in hospital. What the physician pursues directly is for the patient not to attend the event but does so by causing harm. Finally, gross negligence means that the subject does not directly or indirectly pursue the outcome but considers it likely that the outcome may occur through their behavior and, nevertheless, carries out that behavior. For example, a physician uses a new CO2 laser to operate on lesions close to the eye, with no eye protection and using parameters outside those established in the guidelines. The physician seeks to enrich themselves and considers the damage to be somewhat likely but nevertheless carries out the action.

This is in opposition to negligent action. In this case, the subject does not pursue the outcome and, if they had known that the outcome would arise, they would not have acted in that manner. Negligent action includes carelessness or acting recklessly, doing something you should not do even though you do not necessarily know that it may produce the outcome, or you consider the outcome to be very unlikely. For example, you cause a patient with a very poor prognosis to undergo an operation when they should not have been operated on and they die, but you were seeking to cure the patient. Negligence: not doing what you should do, knowing that you should do it. For example, not giving thromboembolic prophylaxis to a bedridden patient. Incompetence: doing something that you do not know how to do and causing an outcome (damage, in our case) as a result. For example, performing a lumbar puncture without the appropriate theoretical and practical knowledge. Once the damage has been determined and the potential malicious or negligent behavior of the physician determined, we establish different routes by which a patient may file a claim.3

Civil RouteThis route may be used when medical malpractice has taken place in a public or private health center or hospital. The objective is to obtain economic compensation, not to convict the physician. It is initiated by filing suit. It is not, therefore, the appropriate route if the negligence takes place in a public health center and the claimant wishes to file a claim directly against the authorities. In the civil route, the cost of the procedure his higher for the patient, as a solicitor and barrister are required, together with a report by a medical expert.

Criminal RouteThis route may also be initiated when medical malpractice has taken place in a public or private health center or hospital. The criminal route is usually used in cases where the negligence has caused severe injury or death to the patient and the aim is to convict the physician with a prison term and have their medical license revoked, as well as obtaining economic compensation. The procedure is initiated when a complaint is filed against a specific physician, team, or health care center. Plaintiffs have a maximum of 3 years to avail of this route. It is a very long procedure and, in general, leads to very few convictions.

Contentious Administrative RouteThis route may be initiated when medical malpractice has taken place in a public health center or hospital. The complaint is filed with the authorities through the center's insurer. It is initiated by filing a complaint or suit with the center's customer-service department. If this department does not respond or if the patient does not agree with the response, an administrative complaint is then filed. The medical center may respond by claiming that it is not liable for the incident. In this case, the patient can initiate a suit with a lawyer, barrister, and medical expert. There is no deadline within which the authorities must respond. In this route, as in the civil route, the aim of the complaint is to obtain economic compensation, not to obtain a criminal (prison) conviction of the physician or have their license revoked or suspended. The authority to which the physician is answerable responds to the claimant. Regardless of whether the authorities satisfy the compensation claim, the claimant has recourse against its agents if they have committed gross negligence or negligence with malicious intent.

How to Prevent ItWhile error is unforeseeable and “to err is human”, there are a number of steps that we must take to ensure that our actions are considered diligent and free of any legal liability. Here, we set out a number of recommendations taken from the literature.4,5

- –

Always act as honestly and professionally as possible. Be thorough in your examination and analysis of the situation and the problem.

- –

Communication with the patient and those accompanying them is essential. Try to show empathy and listen to the patients.

- –

Be careful in the use of language and do not speak disparagingly of the work of other colleagues. Remember, the last doctor to see the patient has the easiest experience.

- –

Do not use expressions such as “I guarantee”, “sure”, etc. Medicine is uncertainty, even in cases that seem clear-cut.

- –

Ensure good, informed consent. Standard consent is not sufficient – it must be as personalized as possible. Give the patient time to understand and think about the decisions and offer your help to ensure that this is the case. If you have any doubts regarding whether something requires written consent, ask for it.

- –

Always remember that it is the patient who decides and make sure they understand this. Explain all the options to them, including the option not to treat, and do not become frustrated or annoyed if the patient does not choose the option that you prefer, if you have explained it correctly and the patient has understood it.

- –

Try to stay up to date. Follow evidence-based medicine and the guidelines set out by recognized protocols. Trust to experience but remember that the exception does not replace the rule.

- –

Exercise care with very novel treatments or treatments far removed from academic orthodoxy. If you are using a drug off-label, this should be indicated in the patient's records, after clearly explaining to the patient the benefits, risks, and evidence, and obtaining the patient's consent.

- –

Ask for advice if the case is beyond your ability. Explain it honestly to the patient and ask your colleagues for help or study the case and suggest a new appointment.

- –

Be very careful when writing up clinical records. Indicate everything and ensure that everything is documented.

- –

Take all legal precautions in the case of patients who appear to be potentially litigious. If treatment is not urgent and/or essential, it is possible to refuse to treat a patient with whom a relationship of trust is absent.

- –

We must know which clinical actions tend to generate more complaints and take the utmost care.

- –

It is important to be able to acknowledge mistakes and apologize for them.

- –

Good civil liability insurance is essential and may be our salvation in the event of litigation.

- –

Having a minimum of medico-legal knowledge in order to practice is very important.

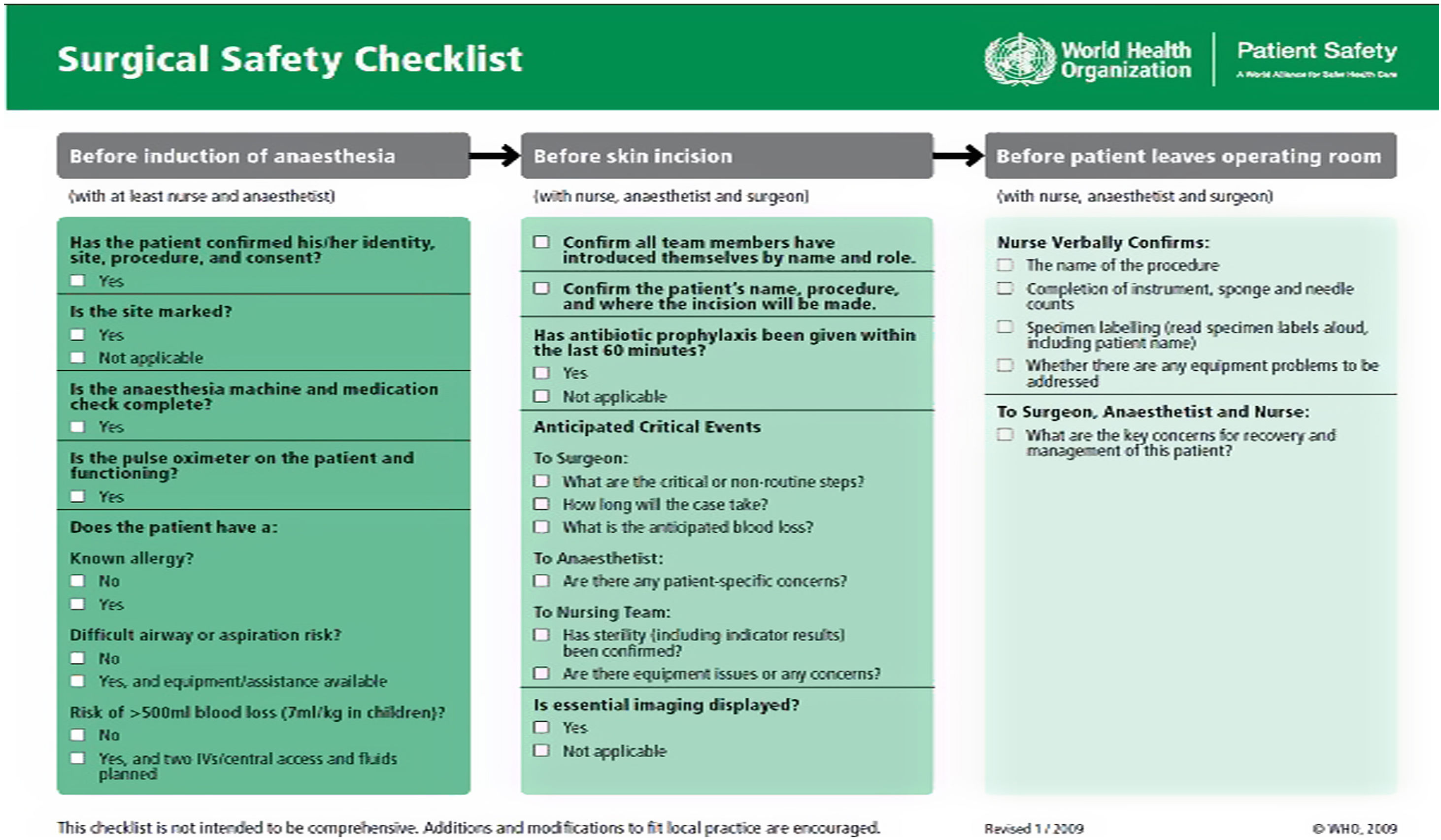

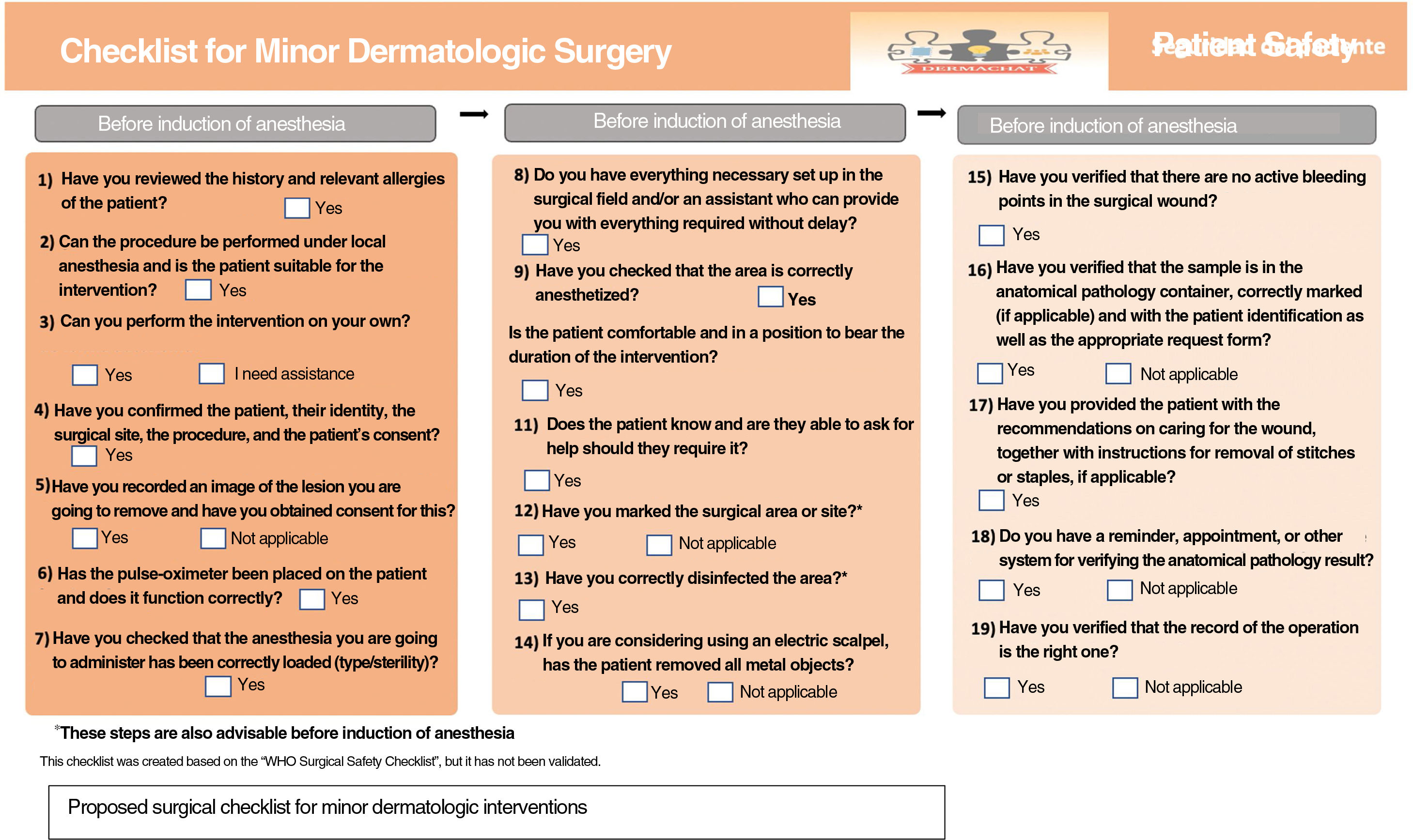

Another very useful tool in surgical specialisms such as ours is the World Health Organization surgical checklist (Fig. 1). This checklist, however, is perhaps restricted to major interventions and we have therefore drawn up a dermatologic checklist (Fig. 1), which is better suited to the needs of our specialism, in the case of biopsies or small interventions (Fig. 2).

How to Deal With ItIn the unfortunate event that you become involved in legal proceedings, here is some advice and useful information.

- –

In the event of a suit, notify the management of the hospital or private center and the civil liability insurance policy issuer, and look for a lawyer who is an expert in the matter as quickly as possible.

- –

Gather all the information possible. Review clinical records, consent, any other persons involved who can prove your innocence, etc.

- –

In most cases, settling out of court is preferable to a trial but always take legal advice in these cases.

- –

Assume that any encounter with the plaintiff may be recorded and that saying “I’m sorry” may be interpreted as an admission of guilt. Therefore, seek advice before holding any conversation of this kind.

- –

Try to avoid the criminal route wherever possible by means of an economic compensation agreement that does not involve a sentence of disqualification or prison.