The simplified psoriasis index (SPI) was developed in the United Kingdom to provide a simple summary measure for monitoring changes in psoriasis severity and associated psychosocial impact as well as for obtaining information about past disease behavior and treatment. Two complementary versions of the SPI allow for self-assessment by the patient or professional assessment by a doctor or nurse. Both versions have proven responsive to change, reliable, and interpretable, and to correlate well with assessment tools that are widely used in clinical trials—the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and the Dermatology Quality of Life Index. The SPI has already been translated into several languages, including French, Brazilian Portuguese, Dutch, Arabic, and Thai.

ObjectiveTo translate the professional and self-assessment versions of the SPI to Spanish and to field test the translations.

MethodA medically qualified native Spanish speaker translated both versions of the SPI into Spanish. The Spanish translations were discussed by comparing them to blinded back translations into English undertaken by native English speakers; the Spanish texts were then revised in an iterative process involving the translators, 4 dermatologists, and 20 patients. The patients scored their own experience of psoriasis with the self-assessment version and commented on it. The process involved checking the conceptual accuracy of the translation, language-related differences, and subtle gradations of meaning in a process involving all translators and a panel of both Spanish- and English-speaking dermatologists, including a coauthor of the SPI.

ResultsThe final self-assessment and professional Spanish versions of the SPI are presented in this manuscript.

ConclusionsCastilian Spanish translations of both versions of the SPI are now available for monitoring disease changes in Spanish-speaking patients with psoriasis under routine clinical care.

El índice de psoriasis simplificado (SPI) fue desarrollado en el Reino Unido con el fin de proveer un resumen métrico para monitorizar los cambios en la gravedad de la psoriasis (SPI-s) y su impacto social asociado (SPI-p), junto con su comportamiento y tratamiento previo (SPI-i). Existen 2 versiones complementarias, una para profesionales de salud, incluidos médicos o enfermeras (proSPI) y otra para la autoevaluación de los pacientes (saSPI). Ambas versiones han demostrado tener una variabilidad al cambio, ser confiables y tener una buena correlación con los instrumentos más utilizados en los estudios clínicos, como el PASI y el DQLI. El SPI estaba ya disponible en versiones adaptadas del francés, portugués (Brasil), holandés, arábigo y tailandés.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del proyecto actual era producir y probar traducciones del proSPI y saSPI al español.

MétodoUn médico hispanohablante realizó la primera traducción de ambas versiones al español. Ambas versiones fueron comparadas con sus contratraducciones al inglés de hablantes nativos, y luego fueron ajustadas en un proceso repetitivo de múltiples pasos conducidas por traductores, 4 dermatólogos y 20 pacientes quienes colaboraron con la evaluación del saSPI. Se verificó cuidadosamente la exactitud conceptual al revisar las discrepancias lingüísticas o diferencias sutiles en los significados en un proceso que involucró a todos los traductores y panel incluyendo dermatólogos de habla inglesa como hispana incluyendo a un cocreador del SPI.

ResultadosSe presentan en este manuscrito las versiones finales acordadas del SPI en español.

ConclusionesLas versiones del SPI en español (castellano) están ahora disponibles para monitorizar clínicamente a los pacientes con psoriasis.

More than 40 scales currently exist to assess severity and response to treatment in patients with psoriasis.1 The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) is the most popular clinical scale in clinical trials and is widely used as the standard benchmark for scoring the severity of psoriasis. This scale, however, has certain disadvantages, such as its complex arithmetic, interobserver variability, low sensitivity in detecting changes in the limited disease, and a lack of standardized cutoff values for categorizing the severity of the disease.2 This is why there is still need for a global consensus to determine the best way to assess psoriasis and its response to treatment. Despite this, many regulatory bodies continue to recommend the use of PASI, although in some cases supplemented with other tools such as the change in global assessment of the disease.3 As well as the potential to underestimate the severity of the disease, the use of PASI also ignores the involvement of special areas, such as the face, palms, soles, genitals, and scalp, its psychological impact, and its impact on quality of life. For this reason, dermatologists must take into consideration the locations of the skin disease and the quality of life in order to achieve a more appropriate and effective assessment.4

The simplified psoriasis index (SPI) was created based on the Salford Psoriasis Index, which was originally designed in the late 1990s with the goal of providing a concise but comprehensive summary of the severity of psoriasis for use in routine clinical practice.2,5,6 The instrument is divided into 3 components that include individual indicators of current severity, psychosocial impact, and past history. When combined, these components contribute to the overall burden of the disease2,3,5–8 (Table 1). The instrument was designed in a dermatology center specializing in psoriasis and later submitted to a group of world experts at the Outcome Measures in Psoriasis Workshop.5

Explanation of the 3 Components of the Simplified Psoriasis Index.

| SPI-s: (current severity) |

| This section considers the functional and additional psychosocial impact on special areas such as the scalp, face, hands, feet, and anogenital area. The extent of the 10 areas assessed is given a score of 0 if the disease is absent or minor, 0.5 if it is obvious, or 1 if it is widespread. Significant nail involvement is included in the severity score of the hands and feet. The current severity score, SPI-s, is the product of the extent score and a general assessment of the severity of the plaque scored from 0 to 5 and reflects the average of all the affected areas.2,3,5–8 |

| SPI-p: (psychosocial impact) |

| The second component (SPI-p) indicates psychosocial impact using a visual analog scale from 0 to 10.3,5–8 |

| SPI-i: (past history and interventions received) |

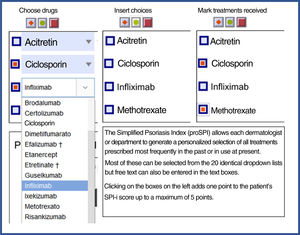

| Finally, the third component was designed to reflect the past history, including duration of the disease and number and type of interventions received. This section includes 4 questions relating to the past history of the disease and 6 relating to prior treatments.3,5,7,8 Templates are available with drop-down fields and free text to produce personalized forms that show the most relevant drugs for each region or department 4). |

The first component reflects current severity (SPI-s) and replaces PASI and percentage BSA.5 This section considers the functional and psychosocial impact on special areas such as the scalp, face, hands, feet, and anogenital area. The extent of the 10 areas assessed is given a score of 0 if the disease is absent or minimal, 0.5 if it is evident, or 1 if it is widespread. Significant nail involvement is included in the severity score of the hands and feet.2,3,5–8 Thus, the SPI-s differs from PASI in that it does not require an estimation of percentage body surface area affected by the psoriasis, which has been shown to be practically impossible to carry out with any degree of accuracy.6,9 The second component (SPI-p) assesses psychosocial impact using a visual analog scale from 0 to 10.3,5–8 Finally, the third component was designed to reflect past history including duration of the disease with a maximum of 4 points, number and type of interventions undergone, with a maximum score of 6 points.3,5,7,8

The SPI is available in 2 versions: the first for use by health care professionals (proSPI) and the second for self-assessment by patients (saSPI).2,3,5–7 Both versions are available for free online.2,5 The sections of the SPI on current severity (SPI-s) and the psychosocial-impact component (SPI-p) correlate significantly with PASI and the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DQLI), respectively, according to studies carried out.2,3,5–8 Those studies support its validity for use in routine clinical practice, as well as its acceptability, reliability and distribution (broad response) for both the proSPI and the saSPI.2,6,7 The good correlation between proSPI and saSPI opens up the possibility of using saSPI to monitor patients remotely.8

Versions are also available in Portuguese (Brazil),10 French,1,8 Dutch,11 Thai,6 and Arabic.12–14 Studies have been carried out to validate the instrument in patients undergoing therapies including phototherapy7 and secukinumab,8 and its use has also been validated in children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis.11

The objective of this project was to produce Spanish translations of proSPI and saSPI and field-test them with Spanish-speaking physicians and patients with psoriasis.

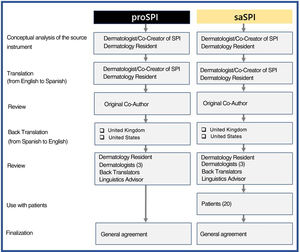

MethodsInitially, a physician whose native language is Spanish translated both versions from English into Spanish. Both versions were then reviewed together with one of the joint creators of this score. Blinded back translations into English were then produced by native English speakers from the United Kingdom and the United States, as described in the adaptation guidelines.15 Both versions were then compared and modified as necessary by a team consisting of translators, an expert in linguistics, 4 dermatologists, including the initial translator, and 20 patients who had volunteered to test and comment on saSPI. All the authors were then able to reach a consensus on the reliability of the 2 translations (proSPI and saSPI) Following are the different stages, tasks, and participants involved in the production of the translations (Fig. 1). The original version and all translated versions of the simplified psoriasis index remain the property of the University of Manchester, which grants free and unrestricted access for the use of the index.

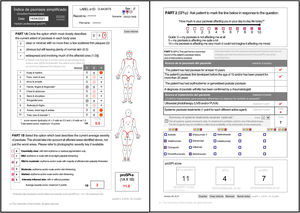

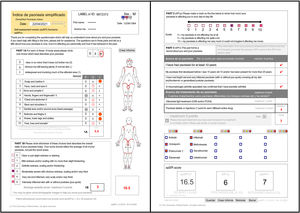

ResultsFollowing is the result of the translation process and the field trials of both versions of the simplified psoriasis index. We show the version of the simplified psoriasis index (proSPI) for professionals (Fig. 2A and B) and the simplified psoriasis index for self-assessment (proSPI) (Fig. 3A and B).

The SPI is divided into 3 sections and, here, we provide a brief explanation of each section.

SPI-sThis section considers the functional and additional psychosocial impact on special areas such as the scalp, face, hands, feet, and anogenital area. The extent of the 10 areas assessed is given a score of 0 if the disease is absent or minor, 0.5 if it is obvious, or 1 if it is widespread. Significant nail involvement is included in the severity score of the hands and feet.2,3,5–8

SPI-pThe second component (SPI-p) indicates psychosocial impact using a visual analog scale from 0 to 10.3,5–8

SPI-iFinally, the third component was designed to reflect the past history, including duration of the disease and number and type of interventions received. This section includes 4 questions relating to the past history of the disease and 6 relating to prior treatments.3,5,7,8 Templates are available with drop-down fields and free text to produce personalized forms that show the most relevant drugs for each region or department (Fig. 4).

Proforma for selecting treatments received. Both versions are available for free online for download. * They can be downloaded from the website: https://globalpsoriasisatlas.org/ under the “SPI” tab (https://www.globalpsoriasisatlas.org/en/simplified-psoriasis-index). * The original version and all translated versions of the simplified psoriasis index remain the property of the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, which grants free and unrestricted access for its use.

The translations were carried out in an iterative process of several stages that involved all the authors with a careful comparison of the back translations with the original instruments.

The most significant point of discussion was the translation of “scale”, a term used deliberately in the SPI to indicate that the thickness of the scale is the relevant parameter for assessment rather than the flaking of the scale. The PASI clinical score has never been revised to clarify this aspect and, therefore, the misleading term desquamation is used as a substitute to assess the thickness of the scale. It was also decided to maintain the terms “escamas” (scales)7 and “descamación” (scaling or peeling) because they were easier terms for patients to understand.

Several linguistic ambiguities were also identified. For example, the term hairline was initially translated as “pelo” (hair) but, after discussion, it was more accurately translated as “línea de implantación del pelo” (hairline). Furthermore, 2 terms, “compromiso” (involvement) versus “extensión” (extent) appeared in Part 1A; after discussion, it was decided to use the term “extensión actual” (current extent). In Part 2 (SPI-i), it was suggested that “con mayor afección” (with greater effect) be changed to “estar más afectado” (being more affected). In Part 3 of the saSPI, it was decided to maintain the sentence “Seleccione cata tratamiento que alguna vez haya recibido” (Select each treatment you have ever received), including the term “alguna vez” to reflect the translation of “ever” in order to cover the entire pharmacological history of the patient. Patients found the interactive version to be “very easy to use”. Four patients suggested a small change to record their gender more simply and these changes were implemented in the final version. Finally, the term “gravedad” was used instead of “severidad” as a better linguistic translation of the term “severity” in the original form.

DiscussionIn this article, we introduce an instrument translated into the Spanish language as a clinical measurement scale for use in routine clinical practice and in clinical trials. This tool has shown a good correlation with PASI and DQLI, both commonly used by dermatologists. The advantages compared to its predecessors include the inclusion of special body sites, giving them a major role in the overall assessment and makes it possible to assess the past history of the disease with treatment history and duration of the disease. Two versions of the scale are available: one for use by health care professionals and the other for self-assessment of the disease; both versions have a significant clinical correlation.

The SPI is an easy-to-use instrument that is available for free and its use has been validated in previous studies, including in special populations such as pediatric patients and patients undergoing treatment with phototherapy or biological therapies. Both Spanish-language versions of the SPI may be downloaded from the Global Psoriasis Atlas website (https://www.globalpsoriasisatlas.org/en/simplified-psoriasis-index), where they can be completed electronically using the interactive PDF files (see figures) or personalized and printed for completion by hand. This scale is also available in English, French, German, Dutch, Portuguese (Brazil), Arabic, and Thai.

The limitations of this project include the fact that the instrument was tested in a relatively small number of patients. The authors invite the dermatology community to experiment with the use of this instrument, which as well as being scientifically validated, provides additional advantages over other well-known scales. In particular, the self-assessment version allows patients to take part in the treatment of their disease and provide their physician with periodic assessments of their response to treatment, and this can be done remotely, if necessary.

FundingNo funding exists for this project.

Conflicts of InterestA.G. Ortega-Loayza is a consultant for Janssen and BMS.

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.