Red ear syndrome (RES) is a syndrome of neurovascular origin that is probably underdiagnosed. It poses both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

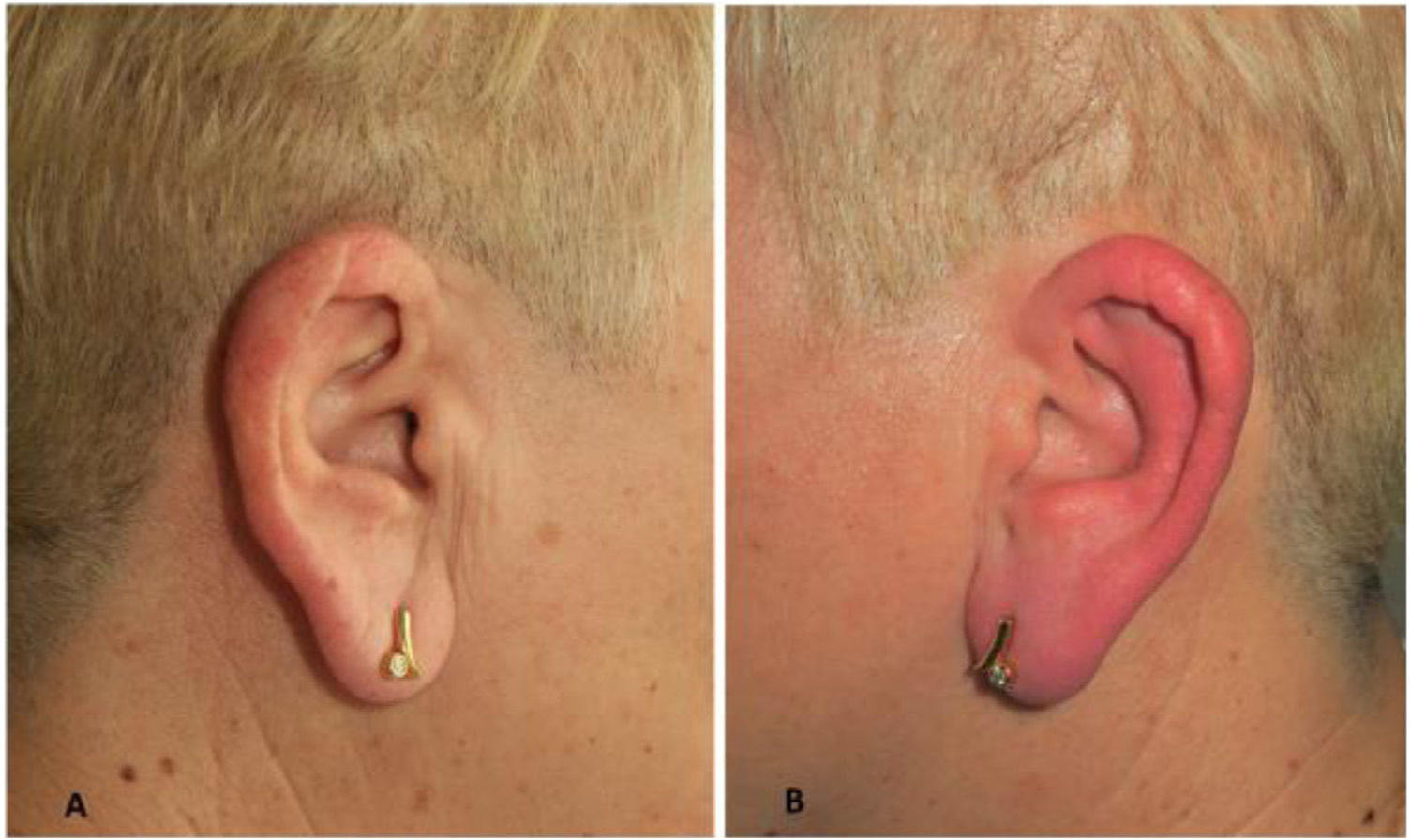

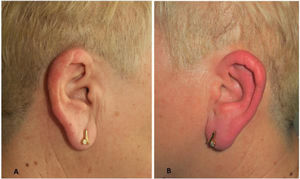

A 66-year-old woman allergic to penicillin presented with a 10-year history of left external ear pain, redness, and swelling that resolved spontaneously within hours or days. The episodes had become more frequent in the previous 6 months, and she was now experiencing 5 a month. Her past medical history included surgical treatment of an ipsilateral jaw fracture 40 years earlier. She had no systemic symptoms, denied use of topical and systemic drugs, and was unaware of any other possible triggers. Physical examination revealed redness and swelling of the left external ear (Fig. 1A and B)

Based on the clinical findings and exclusion of other causes, a diagnosis of RES was made. The patient responded well to conservative treatment with physical measures (including the local application of cold) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

RES was first described by Lance1 in 1994. It is clinically characterized by paroxysmal episodes of redness of the external ear with pain or a burning sensation that can radiate to the ipsilateral cheek, jaw, or occipital area. Attacks can be unilateral (60%), bilateral (30%), or alternating (10%). They usually last between minutes and hours, and their frequency is variable. They occur spontaneously or are triggered by physical stimuli such as hair brushing, teeth cleaning, chewing, ear manipulation, and mobilization of the cervical vertebrae.2

The sensory innervation of the ear is complex. The anterosuperior region of the ear and the tragus are innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve (collateral branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve). The lobe and posteroinferior region are innervated by the greater auricular nerve (branch of the superficial cervical plexus, which is formed by anastomosis between the branches of the C2–C3 cervical spinal nerves). Vascular supply is mainly provided by branches of the external carotid artery (middle temporal and posterior auricular arteries), which, in turn, is sensorially innervated by the trigeminal nerve.3 Vasomotor control of the skin of the outer ear is regulated primarily by variations in sympathetic tone and secondarily by variations in parasympathetic tone. The flushing seen in RES is probably due to excessive vasodilation secondary to activation of parasympathetic fibers and inhibition of sympathetic tone.2

RES can be primary or secondary. In 2013, Lambru et al.4 proposed a series of clinical criteria for diagnosing primary RES (Table 1). Primary RES usually occurs in young women with migraine, during either the prodromal phase or the attacks. Dysfunction of the peripheral cervical nerves or the central nerves of the trigeminal-autonomic pathways has been attributed a possible role in the etiology and pathogenesis of primary RES. Secondary RES, by contrast, is more common in older women without a history of migraine. It can occur in association with intracranial or cervical spine lesions, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, thalamic pain syndrome, herpes zoster, pleomorphic adenoma of carotid body, and toxicity due to drugs such as cytarabine.5

Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Red Ear Syndrome.

| A. At least 20 attacks fulfilling criteria B–E |

| B. Episodes of external ear pain lasting up to 4 hours |

| C. The ear pain has at least 2 of the following characteristics: |

| Burning quality |

| Unilateral location |

| Moderate to intense severity |

| Triggered by cutaneous or thermal stimulation of the ear |

| D. The ear pain is associated with ipsilateral redness |

| E. Attacks occur with a frequency of ≥1 a day, although cases with lower frequency may occur |

| F. Not attributed to other underlying causes |

Source: Adapted from Lambru et al.4

RES must be distinguished from relapsing polychondritis, contact dermatitis, herpes zoster, and erysipelas.6 Pressure urticaria and flushing should also be considered in the differential diagnosis (Table 2).

External Ear Redness and Swelling: Differential Diagnosis.

| Red ear syndrome | Relapsing polychondritis | Contact dermatitis | Herpes zoster | Erysipelas | Pressure urticaria | Flushing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms: P, B, I | P, B | P | B, I | P, B | P, B | I | – |

| Duration of episodes | min/h | Days | Days | Days | Days | min | s |

| Frequency of episodes | Variable | Variable | Variable | Single episode | Single episode | – | – |

| Ear involvement: U or Bi | U>Bi | Bi>U | Bi>U | U | U | Bi>U | Bi |

| Skin signs other than redness and swelling | – | Chondritis | Scaling and blisters | Blisters and crusts | Suppuration and port of entry | – | – |

| Systemic manifestations | – | Fever, nasal or airway chondritis, polyarthritis | Eczema in other body locations | – | – | – | – |

| Triggers | Physical stimulus in area | – | Topical products | – | Seborrheic eczema or insect bite | Pressure | Stress, alcohol, temperature changes |

Abbreviations: B, burning; Bi, bilateral; I, itching; P, pain.

Treatment is based on addressing the underlying cause and achieving symptomatic relief. Results, however, are generally unsatisfactory. Conservative measures include physical therapy, local application of cold or manual compression several times a day, head movements, and use of dental plates. Topical treatments include emollients, corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic treatments are usually reserved for highly symptomatic cases or episodes associated with migraine attacks. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonergic agonists and antagonists, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, antiepileptic drugs, and oral ivermectin have also been used. Invasive procedures involving botulinum toxin injections and nerve blocks with local anesthetics have been used in more severe cases.7

In conclusion, RES is a rare disease that is little known to dermatologists. Exclusion of other clinical entities and possible causes through a detailed physical examination and a targeted history, including medical and surgical history, is crucial.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.