Anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors constitute a new, efficacious therapeutic weapon in the treatment of cancer. Nevertheless, these drugs produce immune-related adverse effects, inherent to their antitumor mechanism of action, which often involve the skin and can lead to their withdrawal. Dermatologic toxicity due to anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 may manifest in highly varied ways, including psoriasis.1 The pathogenesis of psoriasis induced by anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 appears to be attributed to an overactivation of Th1, Th17, and Th22 lymphocytes secondary to inactivation of the PD1 immunomodulatory pathway.2

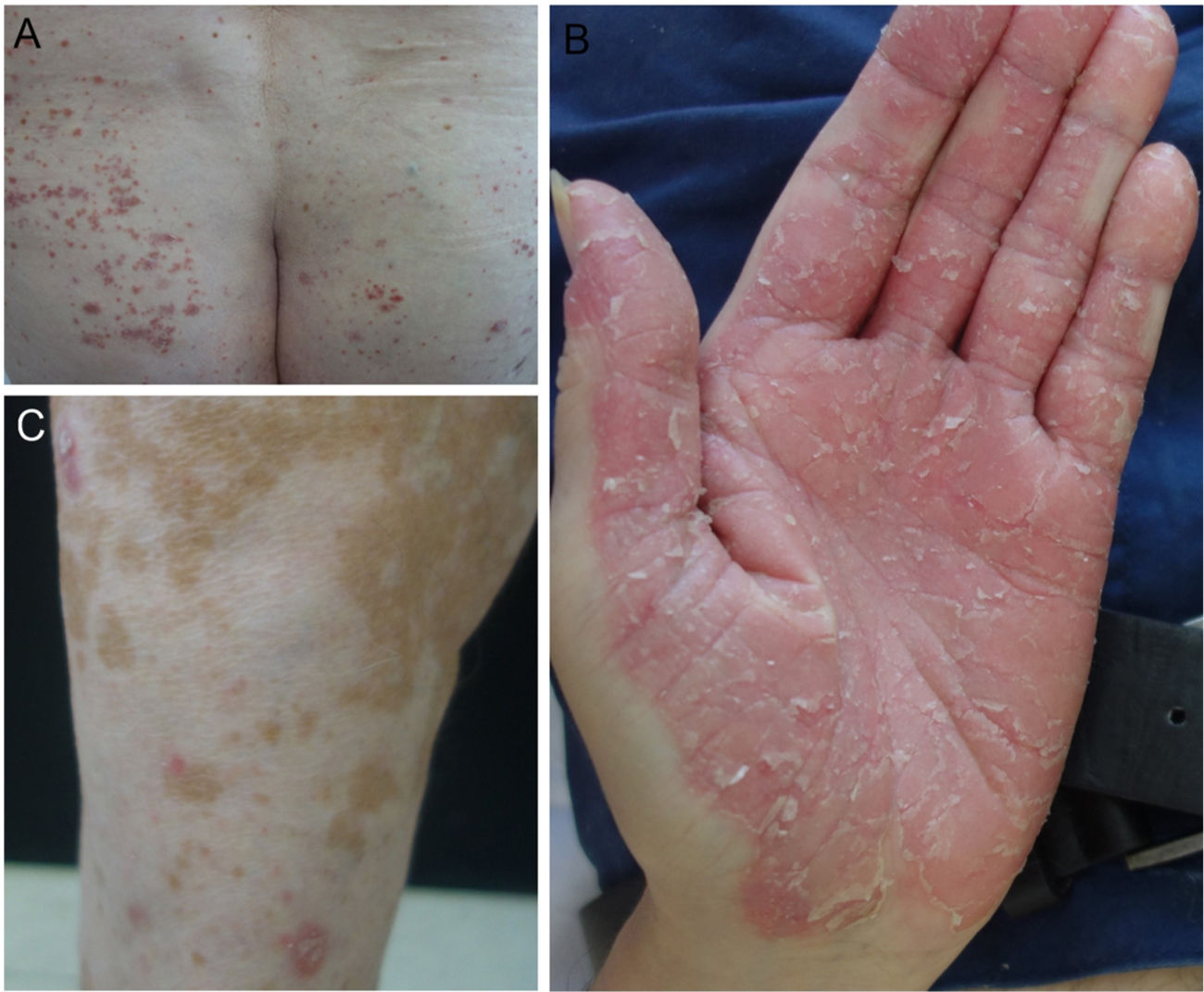

In our hospital, we assessed 3 patients who developed psoriasis as a result of treatment with anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 for gallbladder cancer, cancer of the larynx, and a metastatic melanoma (Fig. 1). We also performed a search of the literature for published cases of psoriasis due to anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 and we recorded the following variables: age, sex, type of tumor, type of anti-PD1/PDL1, dosage regimen used, time to appearance of lesions, personal history of psoriasis, treatment administered, interruption of treatment with anti-PD1/PDL1, and response of tumor to immunotherapy. Finally, we propose an algorithm for the treatment of psoriasis induced by anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1.

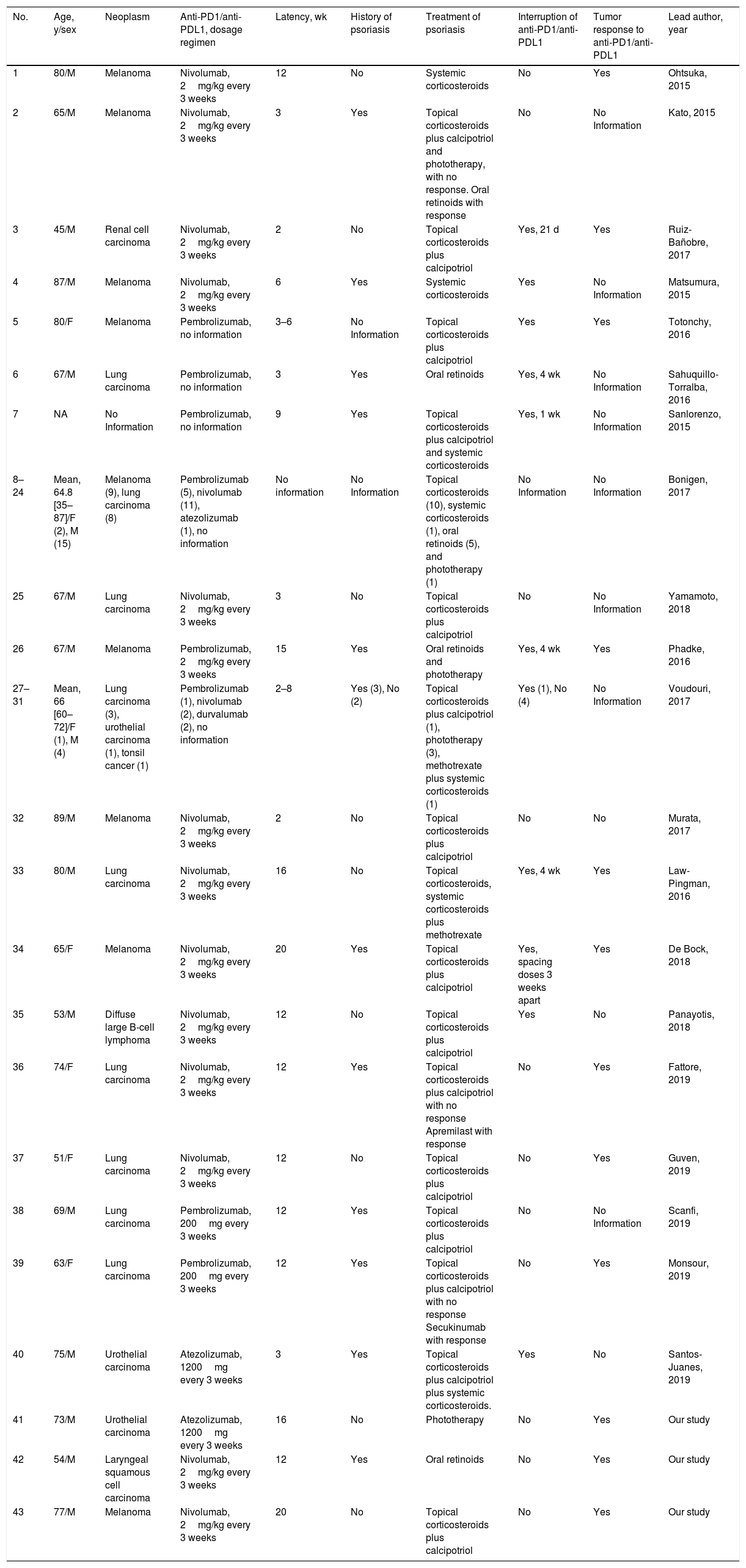

Our patients and the cases published in the literature account for 43 cases of psoriasis induced or exacerbated by anti-PD1 (26 by nivolumab and 12 by pembrolizumab) and anti-PDL1 (3 by atezolizumab and 2 by durvalumab) (Table 1).3–7 The mean age of the patients was 65.7years (35–87 y), with a predominance of males (34/43, 79%). The most frequent types of neoplasia were melanoma and lung cancer, which together accounted for 18 out of 43 cases (41.9%), followed by urothelial carcinoma (3/43, 7%), renal cell carcinoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, tonsil cancer, and squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx (1 case out of 43 each, 2.3%). The mean time from instatement of immunotherapy to appearance of the psoriasis lesions was 9.6weeks. Eleven of the 43 cases stated that they had no personal history of psoriasis (25.6%) and 14 of the 43 presented an exacerbation of their previous psoriasis with anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 treatment (32.6%), although this information was not recorded in many of the published studies. In nearly half of patients, the psoriasis was managed with topical treatment alone (20/43, 46.5%). The most commonly used systemic therapies were oral retinoids (9/43, 20.9%), phototherapy and systemic corticosteroids (5/43, 11.6%, in both cases). Two cases were treated with methotrexate (2/43, 4.7%) and 2 isolated cases received apremilast and secukinumab. Withdrawal of immunotherapy due to psoriasis was not necessary in 15 patients (34.9%), whereas treatment was suspended temporarily in 6 patients (14%) and permanently in 5 (11.6%).

Patients with psoriasis induced or exacerbated by anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 published in the literature as cases or series and their principal characteristics.

| No. | Age, y/sex | Neoplasm | Anti-PD1/anti-PDL1, dosage regimen | Latency, wk | History of psoriasis | Treatment of psoriasis | Interruption of anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 | Tumor response to anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 | Lead author, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80/M | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 12 | No | Systemic corticosteroids | No | Yes | Ohtsuka, 2015 |

| 2 | 65/M | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 3 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol and phototherapy, with no response. Oral retinoids with response | No | No Information | Kato, 2015 |

| 3 | 45/M | Renal cell carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 2 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | Yes, 21 d | Yes | Ruiz-Bañobre, 2017 |

| 4 | 87/M | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 6 | Yes | Systemic corticosteroids | Yes | No Information | Matsumura, 2015 |

| 5 | 80/F | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab, no information | 3–6 | No Information | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | Yes | Yes | Totonchy, 2016 |

| 6 | 67/M | Lung carcinoma | Pembrolizumab, no information | 3 | Yes | Oral retinoids | Yes, 4 wk | No Information | Sahuquillo-Torralba, 2016 |

| 7 | NA | No Information | Pembrolizumab, no information | 9 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol and systemic corticosteroids | Yes, 1 wk | No Information | Sanlorenzo, 2015 |

| 8–24 | Mean, 64.8 [35–87]/F (2), M (15) | Melanoma (9), lung carcinoma (8) | Pembrolizumab (5), nivolumab (11), atezolizumab (1), no information | No information | No Information | Topical corticosteroids (10), systemic corticosteroids (1), oral retinoids (5), and phototherapy (1) | No Information | No Information | Bonigen, 2017 |

| 25 | 67/M | Lung carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 3 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | No | No Information | Yamamoto, 2018 |

| 26 | 67/M | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 15 | Yes | Oral retinoids and phototherapy | Yes, 4 wk | Yes | Phadke, 2016 |

| 27–31 | Mean, 66 [60–72]/F (1), M (4) | Lung carcinoma (3), urothelial carcinoma (1), tonsil cancer (1) | Pembrolizumab (1), nivolumab (2), durvalumab (2), no information | 2–8 | Yes (3), No (2) | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol (1), phototherapy (3), methotrexate plus systemic corticosteroids (1) | Yes (1), No (4) | No Information | Voudouri, 2017 |

| 32 | 89/M | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 2 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | No | No | Murata, 2017 |

| 33 | 80/M | Lung carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 16 | No | Topical corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids plus methotrexate | Yes, 4 wk | Yes | Law-Pingman, 2016 |

| 34 | 65/F | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 20 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | Yes, spacing doses 3 weeks apart | Yes | De Bock, 2018 |

| 35 | 53/M | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 12 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | Yes | No | Panayotis, 2018 |

| 36 | 74/F | Lung carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 12 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol with no response Apremilast with response | No | Yes | Fattore, 2019 |

| 37 | 51/F | Lung carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 12 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | No | Yes | Guven, 2019 |

| 38 | 69/M | Lung carcinoma | Pembrolizumab, 200mg every 3 weeks | 12 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | No | No Information | Scanfi, 2019 |

| 39 | 63/F | Lung carcinoma | Pembrolizumab, 200mg every 3 weeks | 12 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol with no response Secukinumab with response | No | Yes | Monsour, 2019 |

| 40 | 75/M | Urothelial carcinoma | Atezolizumab, 1200mg every 3 weeks | 3 | Yes | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol plus systemic corticosteroids. | Yes | No | Santos-Juanes, 2019 |

| 41 | 73/M | Urothelial carcinoma | Atezolizumab, 1200mg every 3 weeks | 16 | No | Phototherapy | No | Yes | Our study |

| 42 | 54/M | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 12 | Yes | Oral retinoids | No | Yes | Our study |

| 43 | 77/M | Melanoma | Nivolumab, 2mg/kg every 3 weeks | 20 | No | Topical corticosteroids plus calcipotriol | No | Yes | Our study |

Abbreviations: F indicates female; M, male.

The response of the cancer to the anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 is poorly described in these patients. The available data describe a good response in 12 patients and a lack of response in 3. Nevertheless, no correlation appears to exist between the antitumor response and the severity of the psoriasis, as occurs in vitiligo associated with the use of nivolumab for the treatment of melanoma.8

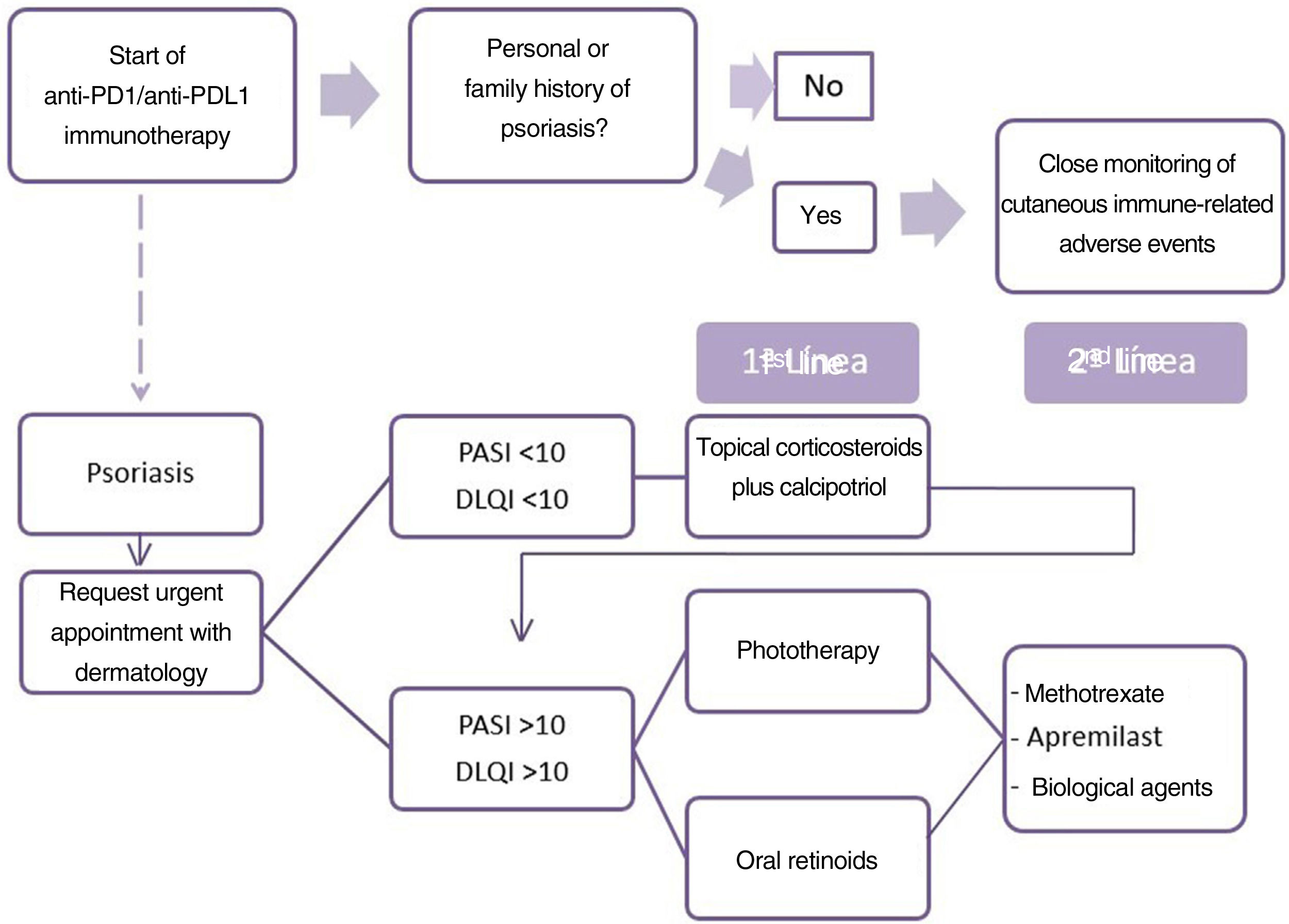

For the treatment of drug-induced psoriasis early recognition, and withdrawal, if possible, of the causal agent is generally recommended, together with the standard therapeutic regimen for psoriasis, in accordance with guidelines.9 The use of cyclosporin is contra-indicated in psoriasis with an underlying cancer. The safety of TNF inhibitors and methotrexate is the subject of debate and little data is available on apremilast and other biological drugs.10 Based on these data, we propose an algorithm for the treatment of patients with psoriasis due to anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1 (Fig. 2). The first point is the need for the oncologist to take a personal and family history of psoriasis from the patient. When psoriasis appears, the patient should be assessed rapidly by the dermatologist. The treatment considered must take into account the extension (PASI) and effect on quality of life (DLQI questionnaire) of the patient's psoriasis. We therefore recommend prescribing topical treatment in mild psoriasis and prioritizing phototherapy and oral retinoids when systemic therapy is required, owing to the immunosuppressant effect of these drugs, due to the possible negative effect on the course of the cancer. In the event of a lack of response or contra-indication, apremilast, methotrexate, or biological treatments may be proposed after agreement with the oncologist.

Dermatologists must learn to recognize and treat the immune-associated cutaneous adverse effects due to anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1, which include psoriasis. Given its frequency, we highlight the need for periodic dermatologic follow-up of these patients. Cooperation with oncology is also essential to accelerate the diagnosis and provide the patients with the best therapeutic option to keep them free of lesions but without negatively affecting the neoplastic disease.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.