Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare, multisystemic, genodermatosis (0.7 cases per 100000 births).1–3

With a highly variable phenotype, its most common clinical manifestations are dermatologic, neurologic, ocular, and dental abnormalities.

Skin changes, a marker of the disease, appear early and characteristically follow the lines of Blaschko in all their stages.1,4

Four sequential stages have been described for typical IP lesions: vesicles (at birth or shortly afterwards), verrucous lesions, hyperpigmentation, and hypopigmentation.

Extracutaneous involvement (neurologic and ocular alterations) determines functional prognosis and leads to irreversible sequelae linked to severe disease.1–7

IP is an X-linked dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the NEMO gene. Between 65% and 75% of cases are caused by sporadic mutations.

IP with an X-linked dominant inheritance pattern is usually lethal in male fetuses, with very few survivors reported.1,5 The International Incontinentia Pigmenti Consortium has proposed 3 mechanisms to explain why some males survive: 1) presence of a concomitant 47,XXY karyotype (Klinefelter syndrome), 2) somatic mosaicism (46,XY/47,XXY), which can only be demonstrated by fluorescence in situ hybridization, and 3) hypomorphic mutations resulting in mild IP. Somatic mosaicism is the most common mechanism.1,5

We describe 2 cases of IP in male neonates and review the diagnostic criteria, etiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and complications of this rare disease.

The first case involved a 4-day-old boy born to a healthy 37-year-old woman following a well-controlled, complication-free pregnancy. The woman had 3 other children, all healthy, from 3 pregnancies. The boy had been born at term (37 weeks) by vaginal delivery. At birth, he had a series of vesiculobullous lesions with yellowish fluid along the lines of Blaschko on the inner aspect of the left leg.

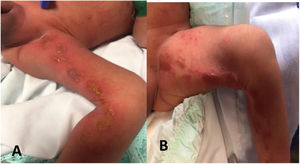

The lesions evolved into verrucous and subsequently hyperpigmented lesions (Fig. 1A and B).

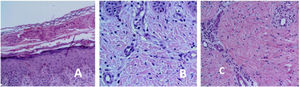

Histopathologic features were consistent with early-stage IP (Fig. 2).

The boy had a 46,XY normal karyotype, and no abnormalities were observed in the fundus examination or the transfontanellar ultrasound. He progressed favorably and was discharged at 15 days of life.

The second case involved a 9-day-old boy born to a healthy 36-year-old mother with a child from another pregnancy. The pregnancy had been well controlled and free of complications. The boy had been born by vaginal delivery at term. At birth, he had vesiculobullous lesions with clear fluid on the right leg; the lesions followed a linear distribution in the dorsal popliteal region. He was discharged at 48h of life without paraclinical tests.

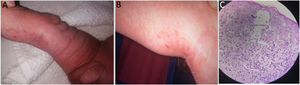

When the boy was 9 days old, the pediatrician examined the lesions, which were verrucous by this stage, and established a presumptive diagnosis of IP (Fig. 3A). The rest of the physical examination was normal.

A and B, Verrucous (stage 2) lesions along the lines of Blaschko. C, Epidermis: spongiosis with intradermal spongiotic vesicles and exocytosis of numerous eosinophils. Dyskeratotic cells with hyaline cytoplasm. Dermis with edema and mononuclear superficial inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils and melanophages.

The area affected by the lesions became smaller, leaving a series of hyperpigmented lesions limited to the popliteal area (Fig. 3B).

The histopathology study showed IP in the vesicular phase (Fig. 3C).

The boy had a 46,XY normal karyotype, and the fundus examination and transfontanellar ultrasound showed no alterations. He progressed well and the skin lesions disappeared spontaneously.

IP is a rare X-linked genodermatosis.1,3,4,6–9 It is seldom diagnosed in male neonates, as its mode of inheritance is normally associated with fetal death.

Few cases of surviving males have been reported worldwide.5,6,9

The presumptive diagnosis is clinical and based on observation of early skin lesions.

Both patients described in this series had vesiculobullous lesions (stage 1) along the lines of Blaschko at birth and subsequently developed verrucous lesions and hyperpigmentation.

Typical skin lesions are considered major criteria for the diagnosis of IP.1–3

According to Rosser,2 2 or more major diagnostic criteria or 1 major and 1 minor criterion are required (Table 1) to confirm diagnosis when there is no evidence of IP in a first-degree female relative and when molecular diagnosis (detection of NEMO mutation) is not available (Table 1).

Diagnostic Criteria for Incontinentia Pigmenti.

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Typical neonatal rash consisting of vesicles and erythema (stage 1) | Dental anomalies |

| Verrucous papules or plaques along the lines of Blaschko (stage 2) | Central nervous system anomalies |

| Typical hyperpigmentation along the lines of Blaschko (stage 3) | Eye anomalies |

| Linear, atrophic, hairless lesions on extremities (stage 4) or scarring alopecia of the vertex | Mammary gland and/or nipple anomalies |

| Palate anomalies | |

| Hair anomalies | |

| Nail anomalies | |

| Multiple miscarriages | |

| Typical skin histopathologic findings |

In all cases eosinophilia or skewed X chromosome inactivation support a diagnosis.

The 2 patients in this series had typical skin IP skin changes (major criterion) and typical histopathologic findings (minor criterion).

Although IP is generally considered lethal in males, there have been some survivors. Proposed mechanisms to explain the small number of survivors reported are the concomitant presence of the 47,XXY karyotype (Klinefelter syndrome) and somatic mosaicism.5,6,8 In both our cases, the karyotype was normal. Based on frequency, somatic mosaicism could explain why these patients survived.

The main entities to be considered in the differential diagnosis are other skin diseases that present with vesiculobullous lesions. Because of their frequency and severity, infectious causes must be ruled out.

In the second case in this series, the patient was not diagnosed at birth, despite the presence of characteristic IP lesions. IP is rare and therefore there is a low index of suspicion among physicians. It is probably underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed in patients with mild forms.

There are clinical cases indicating that mosaicism is common in male patients with IP who do not develop multisystemic disease and who have skin changes that tend to disappear, as in our patients.5,6,8

Central nervous system involvement and eye abnormalities are the main determinants of morbidity and mortality in IP.1,2,5,8 Because these alterations can appear with time, multidisciplinary follow-up and genetic counseling are important.

This study was approved by the ethics committee at Centro Hospitalario Pereira Rossell. Consent for publication was obtained from the patients’ parents.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.