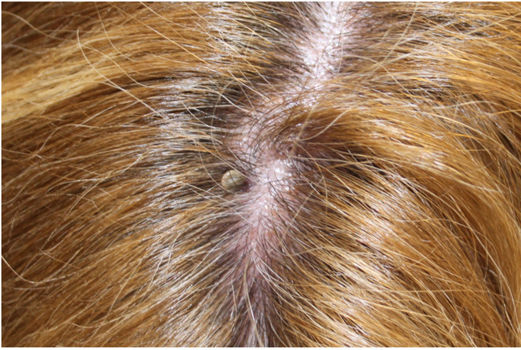

We report the case of a 56-year-old woman, with no relevant past medical history, who presented to the ER last October after finding a tick attached to her scalp (fig. 1). In the 15 days prior, she had been in a rural area. The tick was removed intact, including the hypostome, by gently pulling it out with blunt forceps. Forty-eight hours later, she developed an indurated lesion at the tick bite site, along with low-grade fever spikes (37.8°C), which were noted at the ER.

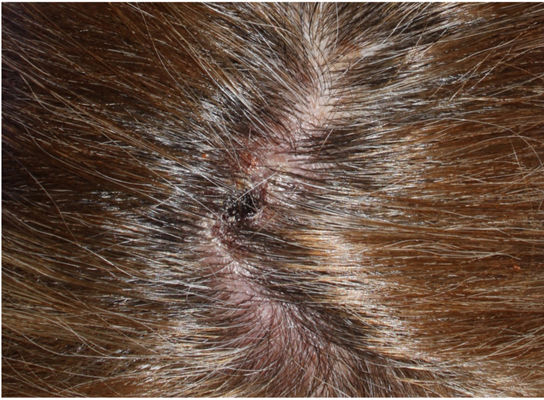

Physical examinationUpon examination, the patient exhibited a necrotic eschar covered by a honey-colored crust at the tick bite site (fig. 2), with no perilesional erythema. The patient also exhibited an ill-defined erythematous and edematous plaque extending from the tick bite site towards the lip region, covering the entire forehead and periorbital region (fig. 3). The patient also exhibited very painful, palpable, bilateral, and cervical lymphadenopathies of anteroposterior location.

Supplementary testsBasic blood tests were performed, including a complete blood count and comprehensive profiling of blood coagulation, which failed to reveal any abnormalities. The liver enzyme levels, however, were elevated: AST (43 IU/L) and ALT (53 IU/L), as well as the C-reactive protein (CRP) (5.37mg/L). Serology for Rickettsia conorii and Borrelia burgdorferi turned out negative. The removed tick was identified as a female Dermacentor marginatus.

What is your diagnosis?

DiagnosisNecrotic eschar and tick-borne lymphadenopathy, also known as TIBOLA.

Course of the disease and treatmentAfter the application of a 15-day daily course of doxycycline 200mg and fusidic acid cream on the honey-colored crust, the symptoms disappeared, the necrotic eschar fell off, and the previously altered PCR and liver enzyme levels went back to normal.

CommentTick bites are a relatively common reason for consultation in Spain, especially in the summertime.1 There are over 800 species of ticks which feed by latching onto the skin, with a preference for folds and the scalp.

In a small percentage of tick bites, complications known as “tick-borne diseases” (TBDs) can occur. There is a certain specificity between each TBD and each tick species. In our setting, the most common TBDs are Lyme disease, transmitted by Ixodesricinus, Mediterranean spotted fever, transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, and necrotic eschar and tick-borne lymphadenopathy transmitted by Dermacentor marginatus. Less common diseases include human anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Additionally, sporadic cases of tularemia and Crimean-Congo fever have been reported.2

Tick-borne lymphadenopathy has been described under various nomenclatures in the scientific medical literature, such as TIBOLA, DEBONEL (dermacentor-borne necrosis erythema lymphadenopathy), or SENLAT (scalp eschar and neck lymphadenopathy). The main causative agents of this disease are Rickettsia slovaca, Rickettsia raoultii, or Rickettsia rioja, being the transmission vector ticks of the Dermacentor genus, which are endemic to Spain.3 Unlike most tick bites, these tend to occur during the autumn and winter months.

This clinical picture should be suspected when a patient has a history of tick bites, a necrotic eschar at the bite site, painful lateral cervical and posterior lymphadenopathies, and low-grade fever or febricula. The diagnosis is primarily clinical.4 Blood tests may show slightly elevated transaminase levels. Some centers have tick identification methods, specific serology, and PCR assay detection of Rickettsia slovaca in the eschar itself.5

Treatment should be started right away on clinical suspicion. Waiting for diagnostic confirmation is ill-advised. The treatment of choice is a 5-to-15-day course of doxycycline 100mg every 12hours.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.