Recent years have seen concerted efforts to understand the relation between psoriasis and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). Not only is MALFD diagnosed more often in patients with psoriasis, but its clinical course is also more aggressive. A common approach is therefore needed to enable early detection of liver disease coincident with psoriasis. Especially important is an analysis of risks and benefits of potentially hepatotoxic treatments. This consensus paper presents the recommendations of a group of experts in dermatology and hepatology regarding screening for MALFD as well as criteria for monitoring patients and referring them to hepatologists when liver disease is suspected.

En los últimos años se están haciendo notables esfuerzos para entender la relación existente entre la psoriasis y la esteatosis hepática metabólica (EHmet). Este trastorno no solo se presenta con una mayor prevalencia en pacientes psoriásicos, sino que además se acompaña de una mayor gravedad. Con este precedente se evidencia la necesidad de establecer un protocolo de abordaje precoz de la enfermedad hepática en los pacientes con psoriasis. Asimismo, es de especial relevancia la evaluación del riesgo y del beneficio en referencia al uso de tratamientos con potencial hepatotóxico. En el presente manuscrito se exponen las recomendaciones de un panel de expertos en dermatología y hepatología para el cribado, el diagnóstico, la monitorización y los criterios de derivación en pacientes con psoriasis, en caso de sospecha de esteatosis hepática metabólica.

Approximately 125 million people worldwide (1%–3% of the world's population) have psoriasis, and more than 1 million of these are in Spain (2.69% of the country's population).1,2 Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease that works synergistically with other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.2,3 Understanding the impact of associated comorbidities is essential for enabling comprehensive clinical management.2

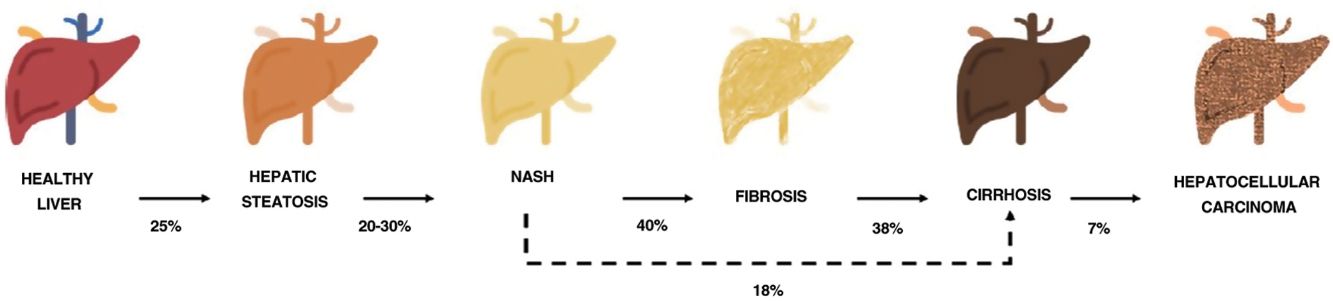

One of the comorbidities associated with psoriasis is what has to date been known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. In this review, we will refer to this disease using the new term agreed on by the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver (AEEH) following a Delphi process: metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, or MAFLD.4 MAFLD comprises a spectrum of hepatic lesions ranging from fat accumulation in the liver, which is a metabolic disorder considered to have a low risk of progression, to steatohepatitis, an inflammatory disorder that can progress to cirrhosis and its complications. MAFLD is generally asymptomatic and occurs in association with metabolic syndrome (MetS).5 It is in fact recognized as the hepatic manifestation of this syndrome and can precede other manifestations.6,7 MetS is a group of metabolic disorders among which hepatic disorders are considered particularly significant.6,7 MALFD has a wide clinical spectrum (Fig. 1) with a dynamic course characterized by periods of progression, regression, and stability.8,9 This variability can in part be explained by genetics and lifestyle changes, but factors such as age, sex, race, alcohol consumption, and gut microbiota also influence clinical presentation and responses to treatment.5

Progression of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. From steatosis (stable, with little risk of progression, characterized by the accumulation of intracellular fat in the hepatocyte) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (fat accumulation accompanied by inflammatory changes and cell damage) and hepatic fibrosis (collagen deposition in the form of fibrous septa that cause architectural remodeling and progressive hepatocyte dysfunction). Fibrosis predisposes to the development of cirrhosis (fibrotic septa and regeneration nodules) and hepatocelular carcinoma and/or liver failure.6,8,10,12–14

The prevalence of MALFD is rising progressively, in line with that of MetS, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.8,10 MALFD is estimated to affect 25% of the population and 55.5% of people with type 2 diabetes. Although the percentage of patients with MALFD who develop nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is unknown, it is in excess of 10%. The prevalence of biopsy-proven NASH in patients with MAFLD appears to have increased in recent years from 29.9% to 59.1%.5

NASH progresses to fibrosis in 40.76% of cases.8 The estimated prevalence of MAFLD in Spain is 25.8%, while that of significant fibrosis estimated by sequential combination of transition elastography (TE) and liver biopsy is 2.8%.10

Prognosis in MALFD is influenced by progression to NASH, fibrosis, and comorbidities. Advanced fibrosis increases the risk of liver-related morbidity and mortality.10,11 MALFD thus constitutes a significant health problem and a major reason for liver transplantation.9,12

The evidence supporting the relationship between psoriasis and MAFLD is substantial.15 In general, MAFLD is more common in patients with more severe psoriasis.16,17 Phan et al.,15 corroborating previous findings,18 showed that patients with psoriasis were twice as likely to have MAFLD as those without psoriasis. In Spain, the percentage of patients with psoriasis and MAFLD is 42.3%.19 A direct correlation has also been observed between psoriasis severity and liver disease severity.20 One cross-sectional study found that advanced fibrosis was more common in patients with psoriasis than in healthy controls, and that psoriasis was a significant predictor of advanced liver fibrosis independently of age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and diabetes.21 Psoriasis is currently recognized as an independent risk factor for MAFLD.22,23 Likewise, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and obesity are the main risk factors for MAFLD in patients with psoriasis. The association between psoriasis and MAFLD is independent of confounders, confirming a shared pathophysiology involving inflammatory pathways and genetic predisposition.15 Psoriasis and MAFLD have a common etiology of low-intensity chronic inflammation involving adipokines that participate in energy balance and inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL] 17, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IL-6]).3,24,25

The above findings suggest that early screening for MAFLD is necessary in patients with psoriasis.26 The AEEH recently published a consensus statement on the detection of prevalent occult liver diseases and referral criteria. Among its conclusions with clinical implications were 1) chronic liver disease should be screened for and monitored in patients with immune-mediated skin disorders and 2) chronic liver disease is more common in this setting due to immunological and inflammatory mechanisms and hepatotoxicity.26

To encourage multidisciplinary management and update current recommendations on screening, diagnosis, monitoring, and referral for MAFLD in patients with psoriasis, we formed an expert panel to design a set of consensus-based recommendations based on current evidence and real-world experience.

MethodologyA working group of 12 experts with experience in the management of psoriasis and MAFLD—7 dermatologists and 5 hepatologists—was formed to prepare this document. The methodology was based on the so-called formal method.27,28 The group began by reviewing the current evidence and completing several purpose-designed questionnaires on psoriasis and risk of liver disease to identify key points related to detection, screening, diagnosis, and management. Over the course of 3 meetings, the group analyzed clinical aspects related to the definition and management of at-risk patients. At a final meeting, they agreed on an algorithm for managing these patients, which included practical diagnostic and monitoring recommendations based on the main clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and the clinical experience of the members of the panel.

Identifying Risk Factors for Liver Disease in Patients With PsoriasisThe expert panel recommends screening for liver disease in patients with psoriasis according to current Spanish CPGs,29,30 regardless of treatment or time since diagnosis, if at least 1 of the criteria accompanying steatosis in a diagnosis of MAFLD is present31: overweight or obesity, T2D, and/or evidence of metabolic dysregulation. These criteria are as follows:

- •

Waist circumference≥102cm in men and ≥88cm in women

- •

Blood pressure≥130/85mmHg or specific drug treatment

- •

Plasma triglycerides≥150mg/dL (≥1.70mmol/L) or specific drug treatment

- •

Plasma HDL cholesterol<40mg/dL (<1.0mmol/L) for men and <50mg/dL (<1.3mmol/L) for women, or specific drug treatment

- •

Prediabetes (fasting glucose levels 100–125mg/dL [5.6–6.9mmol/L] or 2-h postload glucose levels 140–199mg/dL [7.8–11.0mmol/L] or HbA1c 5.7%–6.4% [39–47mmol/mol])

- •

HOMA-IR (homeostatic model of assessment for insulin resistance) score≥2.5

- •

Plasma high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level>2mg/L

Patients with psoriasis and at least 1 risk factor for MetS should be screened for the risk or presence of liver disease. As MAFLD is a silent disease, national and international CPGs recommend using noninvasive methods such as the Fibrosis-4 Index for Liver Fibrosis (FIB-4) for the early detection of risk factors for the different stages of MALFD (from steatosis to advanced stages such as fibrosis).10,30,31 Transaminases should not be explored in isolation for the early diagnosis of MAFLD, as levels can be normal, even in patients with advanced fibrosis.32

Screening Recommendations for MetSOnce an at-risk patient is identified, the first step in the proposed screening and follow-up algorithm (Fig. 2) should be applied.

Screening algorithm for patients at risk of MAFLD. Depending on the situation of each hospital and test availability, the dermatology department can order TE or refer the patient to the gastroenterology department. MAFLD indicates metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4 Index for Liver Fibrosis; HFS, Hepamet Fibrosis Score; TE, transient elastography. aTE should be performed to evaluate the risk of fibrosis in patients with a low FIB-4 score and under a potentially hepatotoxic treatment.

Consensus is lacking on which noninvasive diagnostic tools, or cutoffs (Table 1), should be used instead of liver biopsy to screen for MAFLD.10,22,31 Liver biopsy is the current gold standard,33 but it is not without complications. The CPGs recommend combining serum-based testing and TE, as this reduces the need for biopsy by approximately 50% to 60% and secures an accurate diagnosis.34 Serum-based fibrosis tests are the first-choice option for screening purposes, with TE to be used in patients considered at high risk.

Noninvasive Tests for Diagnosing Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease.

| Test | Stage | Parameters | Risk of advanced fibrosis according to cutoff values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSI41 | Steatosis | ALT/AST, BMI, sex, diabetes | <30: low>36: high | |||

| FLI42 | Steatosis | Waist circumference, BMI, triglycerides, GGT | <30: low30–59: intermediate≥60: high | |||

| NAFLD-FS43 | Fibrosis | Fasting blood glucose or diabetes mellitus, age, BMI, ALT, AST, platelets, albumin | <−1.455: F0-F2, low−1.455–0.675: indeterminate>0.675: F3-F4, high | |||

| FIB-444 | Fibrosis | Age, ALT, AST, platelets | <1.30: F0-F2, low>2.67: F3-F4, high | |||

| HFS40 | Fibrosis | Sex, age, diabetes, glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR (no diabetes), AST, albumin, platelets | HFS score | F2-F4 | F3-F4 | F4 |

| <0.12 | 23.6% | 8.1% | 0.9% | |||

| 0.12–0.47 | 57.1% | 33.7% | 7.4% | |||

| >0.47 | 86.4% | 76.3% | 35.5% | |||

| APRI45 | Fibrosis | AST, platelets | F0-F2: <0.5; 72.7%F3-F4: >1.5; 54.2% | |||

| BARD score46 | Fibrosis | ALT, AST, diabetes, BMI | 0–1: low2–4: high | |||

| ELF47 | Fibrosis | HA, PIIINP, TIMP-1 | <7.7: zero or low≥7.7–9.7: moderate≥9.8 high | |||

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis test; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; HFS, Hepamet Fibrosis Score; HOMA, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; HSI, hepatic steatosis index; NAFLD-FS, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score; PIIINP, procollagen III amino-terminal peptide; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1.

Table 1 lists a number of noninvasive liver fibrosis screening tests. The expert panel considers FIB-4 to be most suitable test for initial screening in dermatology units: it has been externally validated for fibrosis screening in patients with fatty liver disease, is readily available and easy to process, and is recommended by CPGs.10,22,31 FIB-4 takes account of platelet count, age, and aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase values. It has high negative predictive value (NPV) for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis (stage F3-F4), meaning that liver biopsy can be avoided.35,36 A score of less than 1.30 rules out advanced fibrosis with an NPV of 85%. Scores of more than 2.67 indicate advanced fibrosis with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 79%.37 A number of factors, however, must be considered, including the risk of false positives from PPVs, a relatively high probability (1 in 3) of intermediate scores (1.30–2.67), and the influence of age on the accuracy of predictions (a threshold score of 2 is recommended for people aged over 65 years).38

The accuracy of FIB-4 depends on age: the index is not suitable for people younger than 35 years, and more tailored cutoffs are needed to improve its specificity in those older than 65 years.39 Another serum-based tool, the HEPAMET Fibrosis Score (HFS), offers greater specificity (higher predictive values than FIB-4) and accuracy, resulting in less diagnostic uncertainty. Its only limitation is that it includes HOMA-IR, which is generally not a routinely ordered test.40

When serum-based testing indicates a low risk, twice-yearly dermatologic follow-up with reassessment of risk is recommended.31 TE is recommended in patients with a medium to high risk.31,38,48 It has proven effective for monitoring disease severity, has high diagnostic accuracy for advanced stages of fibrosis (F3-F4), correlates with clinical findings,49,50 and, as a noninvasive test, does not increase risk. It should be noted that a high FIB-4 score indicates increased risk, regardless of TE results. Decisions to refer a patient for TE should therefore be based on availability and expected usefulness (whether or not it will influence outcomes). Patients with an intermediate FIB-4 score should be referred for TE due to the high level of uncertainty.

Wong et al.51 showed that a TE cutoff of 7.9kPa had the highest accuracy (sensitivity, 91%; specificity, 75%; and positive predictive power, 97%) for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with MAFLD. The recommended cutoff for high-risk patients is therefore 8kPa. Patients with a high FIB-4 score and a TE value of 8kPa or lower should be reassessed annually using FIB-4 and/or a repeat TE if available.

Patients with a TE value of more than 8kPa and a risk of advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) should be referred to the gastroenterology department for evaluation of the most appropriate management strategy (Fig. 2). If TE is not available, patients with a high FIB-4 score should be referred to a gastroenterologist.

Current Treatments for Psoriasis and Their Impact on MAFLDThe expert panel recommendations are general guidelines for common clinical situations that should be applied according to the criteria of each specialist.

CPG diet and exercise recommendations are the mainstay treatment for MAFLD.31 Weight reductions of 10% or more can resolve NASH and reduce fibrosis severity by at least 1 stage. Minor weight loss (5%–10%) can improve certain components of MAFLD. A Mediterranean diet, even without weight loss, reduces liver fat content.52

A number of drugs are currently under development for MAFLD. Details of clinical trials evaluating their efficacy and safety are summarized in Table 2.

Clinical trials evaluating treatments for metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

| Target | Drug | Action | Phase | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes, insulin resistance | Semaglutide | GLP-1 receptor analog | II | 54 |

| Canagliflozin | SGLT2 inhibitor | Pilot | 55 | |

| BMS-986036 | Recombinant FGF21 | II | 56 | |

| Dyslipidemia | Aramcol | SCD inhibitor | III | 57 |

| Firsocostat (GS-0976) | ACC inhibitor | II | 58 | |

| Nuclear receptor | Obeticholic acid | FXR agonist | III | 59 |

| Elafibranor | PPARα/δ agonist | III | 60 | |

| Resmetirom (MGL-3196) | TRβ agonist | III | 61 | |

| Apoptosis | Emricasan | Capsase inhibitor | II | 62 |

| Inflammation, fibrosis | Selonsertib | ASK1 inhibitor | III | 63 |

| Cenicriviroc | CCR2/5 antagonist | III | 64 | |

| GR-MD-02 | Galectina-3 inhibitor | I | 65 | |

| JKB-121 | TLR4 antagonist | II | 66 | |

| ND-LO2-s0201 | HSP47 siRNA | II | 67 |

Abbreviations: ACC, acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase; ASK1: apoptosis signal-regulatory kinase 1; CCR2/5, chemokine coreceptor type 2/5; FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GLP1, glucagon-like peptide 1; HSP47 siRNA: heat shock protein 47 small interfering ribonucleic acid; PPARα/δ, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptorα/δ; SCD, stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; TRβ, thyroid hormone receptor β.

MetS factors should be evaluated in patients without severe liver disease who have a TE value of 6 to 8kPa, regardless of FIB-4 score. Determining the degree of metabolic disease is important for estimating the risk of progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.7 The results of this assessment will determine the need for follow-up and further tests in accordance with the respective recommendations (annual follow-up and repeat FIB-4).

Patients with psoriasis and liver disease have an increased risk of drug-induced hepatotoxicity (Table 3).68 Methotrexate is the most widely used conventional systemic drug in moderate to severe psoriasis due to its cost-effectiveness and the extensive experience with its use. It is, however, hepatotoxic and can cause fibrosis.69–71

Drugs Used to Treat Psoriasis and Their Impact on the Liver.

| Drug | Toxicity | Type of damage | Liver failure | Increased risk of liver damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate69–73 | +++ | Oxidative damage | Use with precautionContraindicated if TBIL>5mg/dL | MAFLD/obesity, leflunomide, alcohol |

| Acitretin74,75 | ++ | Mitochondrial dysfunction | Contraindicated | Elevated transaminases 15%-30%75 |

| TNF inhibitors76–78 | ++ | Liver failure, noninfectious hepatitis, hepatic insufficiency | NA | Increased risk of liver damage with adalimumab79 and autoimmune hepatitis with infliximab78 |

| IL-12/23 antibodies79 | + | NA | N/A | NA |

| IL-23 antibodies80–82 | + | Elevated transaminasesa | NA | NA |

| IL-17 antibodies83–85 | NA | NA | NA | Possible protective effect against inhibition of IL-17A in animal models86 |

| Apremilast87 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cyclosporine88 | Rare | Oxidative damage | SafeDose reduction required | Obesity |

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; NA, not applicable (no studies); TBIL, total bilirubin.

The group of TNF inhibitors includes etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab. The group of IL-17A inhibitors includes brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. The group of IL-23 inhibitors includes tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab.

A recent study of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis treated with methotrexate in Spain showed a correlation between treatment duration and risk of liver fibrosis.72 The percentage of patients with a high risk (FIB-4>1.3) increased from 18.2% when patients received methotrexate for 16 to 24 weeks to 27.3% when they were treated for 52 to 104 weeks and 32.3% when they were treated for longer.72 Shetty et al.71 suggested that the intensity and frequency of monitoring should be tailored to individual risk factors and emphasized the increased risk of methotrexate-induced liver damage in patients with NASH or NASH-fibrosis.

Patients under treatment with steatogenic drugs should also be monitored for liver damage.68 According to a recent CPG, amiodarone, methotrexate, tamoxifen, and the chemotherapeutic agents 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan are risk factors for MAFLD and should be maintained or withdrawn based on their potential to protect against progression to liver disease (grade B recommendation based on extrapolation from level 1 evidence studies).89

TE is recommended in patients with a low FIB-4 score under hepatotoxic treatment.70,89,90 The decision whether to continue treatment with a hepatotoxic drug in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and a TE value of 8kPa or lower (tested because of a high FIB-4 score or reevaluated with a low FIB-4 score due to treatment) should be based on an individual risk-benefit analysis and the recommendations of the hepatologist. Hepatotoxic drugs are not recommended in patients with a high FIB-4 score and/or a TE of more than 8kPa due to the risk of advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) (Table 4).

Characteristics of Moderate to Severe Psoriasis in Candidates for Systemic Treatment According to the Definitions of the Psoriasis Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).29

| Psoriasis severity scores | BSAa 10% or PASIb>10 or DLQIc>10 |

| Location | Visible areas (face and dorsum of hands), palms, soles, genitals, scalp, nails, and also recalcitrant plaques with a functional or psychological impact |

| Previous treatment failure | Not controlled by topical therapy or phototherapy |

Body surface area (BSA) is one of the most widely used scales to assess psoriasis severity.91 BSA is calculated from the arithmetic mean of the affected skin surface weighted according to the total area occupied by each part of the body evaluated: the head represents 10% of the total body surface, the upper extremities 20%, the trunk 30%, and the extremities less than 40%.92

The Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) is the most widely used measurement scale for assessing the extent and severity of psoriasis and guiding treatment decisions. This index combines a severity score ranging from 0 to 4 assigned to each psoriasis lesion (0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=marked, 4=very marked) in 4 parts of the body (head, trunk, upper limbs, and lower limbs). The score is based on 3 parameters: erythema, induration, and desquamation.92,93

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is composed of 10 questions on the extent to which a person's skin problem has affected their life over the past week. Each question has 4 possible answers: not at all (0), a little (1), a lot (2), very much (3). The scores (0–3) are added to obtain a total score. A higher score indicates worse quality of life.94

Agreement among dermatologists and hepatologists on simple, evidence-based, criteria to identify, diagnose, and monitor at-risk individuals is essential for the efficient management of MAFLD. General recommendations should be tailored to the specific characteristics, needs, and organizational and care delivery set-ups of different hospital and health care providers.

Potential interactions between psoriasis treatments and MAFLD must be taken into account, with consideration of both the prevalence of liver disease and the potential and diverse impacts of these treatments. Decisions on whether to continue with a potentially hepatotoxic treatment in patients with a risk of liver fibrosis should be taken after weighing up the risks and benefits. Individual evaluation and follow-up is necessary.

Of all the treatments investigated, methotrexate is the only one associated with an increased risk of new-onset or worsening MAFLD. There is no evidence that phototherapy or certain new-generation conventional treatments cause hepatotoxicity in patients with hepatic steatosis. Although most biologic therapies have a favorable risk-benefit profile in patients with steatosis and varying degrees of fibrosis, their hepatotoxic potential is diverse (Table 3).92

ConclusionsConsidering the prevalence of MAFLD in patients with psoriasis and the interconnections between these diseases, we recommend screening for liver disease and certain components of MAFLD in patients with psoriasis, regardless of the presence or extent of liver biochemistry abnormalities. This screening should be a routine part of psoriasis care in dermatology departments and clinics. The first-choice strategy is to use a combination of FIB-4 and TE and to refer patients to the hepatology department when a significant risk of advanced fibrosis is detected.

FundingThe expert panel meetings were funded by Novartis Farmacéutica S.A.

Conflicts of InterestThe expert panel meetings were funded by Novartis, but none of the employees at this company participated in the design or production of the scientific material, any of the discussions, or the resulting manuscript.

Antonio Olveira has participated as a researcher, speaker, or consultant in projects sponsored by Abbvie, Alexion, BMS, Janssen, MSD, Gilead, and Novartis.

Isabel Belinchón has served as a consultant and/or speaker and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by companies that make drugs used to treat psoriasis, including Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., Almirall SA, Lilly, Abbvie, Novartis, Celgene, Biogen, Amgen, LEO Pharma, Pfizer-Wyeth, MSD, and UCB.

Pedro Herranz has participated as a researcher, speaker, or consultant in projects sponsored by Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, and UCB.

Javier Crespo has participated as a researcher, speaker, or consultant in projects sponsored by Abbvie, Alexion, BMS, Amgen, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, and MSD.

Eva Vilarrasa has received consultancy/speakers’ fees from and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Gebro, Isdin, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, and UCB.

Salvador Benlloch Pérez has participated as a researcher, speaker, or consultant in projects and clinical trials sponsored by Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Gilead.

Jorge Alonso Suárez Pérez has served on a steering committee and/or participated as a guest speaker for Novartis, LEO Pharma, Abbvie, Lilly, Janssen, UCB, Amgen, and Almirall.

José Manuel Carrascosa has served as a principal investigator/co-investigator and/or was a guest speaker for Novartis, LEO Pharma, Abbvie, Lilly, Janssen, UCB, Sandoz, Mylan, Amgen, Almirall, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Javier Ampuero declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Francisco Guimerà declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

GACPE, the Working Group for a Common Approach to Psoriasis and MAFLD, is composed of 7 dermatologists and 5 hepatologists with experience in managing psoriasis and MAFLD. The respective experts are listed below.

Jorge Alonso Suárez-Pérez. Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga, Spain.

Susana Armesto Alonso. Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain.

Isabel Belinchón Romero. Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica (ISABIAL), Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, Alicante, Spain.

José Manuel Carrascosa Carrillo. Departamento de Dermatología. Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. IGTP Badalona, Spain.

Francisco Guimerá Martín-Neda. Servicio de Dermatología y Patología, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, La Laguna, Spain.

Pedro Herranz Pinto. Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

Eva Vilarrasa Rull. Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Javier Ampuero Herrojo. Departamento de Enfermedades Digestivas, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío. Laboratorio 213, Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla (IBIS). Departamento de Medicina, Universidad de Sevilla. Centro Biomédico en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd). Sevilla, Spain.

Salvador Benlloch Pérez. Servicio de Enfermedades Digestivas, Hospital Arnau de Vilanova. Valencia. Centro Biomédico en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd). Valencia, Spain.

Javier Crespo García. Servicio de Gastroenterología y Hepatología. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. IDIVAL. Escuela de Medicina. Universidad de Cantabria. Santander, Spain.

Antonio Olveira Martín. Servicio de Aparato Digestivo, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.