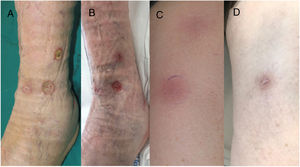

An 85-year-old man presented with erythematous, hot, and painful subcutaneous nodules arranged linearly along the anterolateral area of the left leg and the anterior region of the left thigh. They had appeared 3 weeks earlier and had progressed to form intensely painful ulcers (Fig. 1). Four years earlier, the patient had been diagnosed with an ulcerated retroauricular melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 1.87mm (pT2b pN0 MO; stage IIA, American Joint Cancer Committee Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition). He denied any other associated symptoms and confirmed that he had not had any recent infections or started any new drugs. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

A, Deep ulcers with an erythematous border and a fibrinous base that persisted despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral corticosteroids, and local dressings. B, Reduction in the diameter and depth of ulcers after 2 cycles of pembrolizumab. C, Linear, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules in the lower limbs. D, Complete resolution of nodules with mild postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after 2 cycles of pembrolizumab.

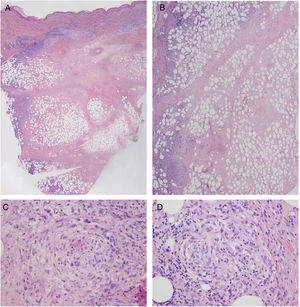

Laboratory findings, including autoantibodies, were normal, and the Mantoux test and interferon gamma release assay were negative. Doppler ultrasound showed no signs of thrombosis or thrombophlebitis. Histologic examination of 1 of the lesions showed a preserved, unaltered epidermis but extensive dermal and subcutaneous necrosis with a predominantly lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the septa and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue. Atypical lymphocytes were not observed. Additional findings included signs of vasculitis and scant numbers of histiocytes and lymphocytes forming granulomas (Fig. 2). Cultures were negative. Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of nodular vasculitis was established.

Chest radiography and a total body computed tomography scan revealed a solid nodule at the base of the right lung. Fine-needle aspiration showed findings compatible with BRAF wild-type metastatic melanoma.

Having ruled out all other possible causes, the patient was diagnosed with paraneoplastic nodular vasculitis associated with metastatic melanoma. The lesions did not respond to treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral corticosteroids, or local wound care with hydrocolloid dressings. According to the indications of the oncology department, the patient was administered pembrolizumab 200mg every 3 weeks. After 2 cycles, the lung metastases reduced in size, the subcutaneous nodules disappeared, and all the ulcers showed a reduction in diameter and depth. Unfortunately, the patient fell 4 months after starting treatment and sustained a head injury that required prolonged hospitalization and discontinuation of chemotherapy. His condition progressively deteriorated and he died 2 months later.

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are skin manifestations that are detected before, concurrently with, or after the diagnosis of malignancy. In 1976, Curth proposed 6 criteria for identifying a paraneoplastic dermatosis (Table 1), but most authors now agree that the first 2 criteria are sufficient to determine a link.1

Curth's postulates for paraneoplastic dermatoses. These criteria are used to determine a consistent relationship between an internal malignancy and a dermatosis.

| Criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Concurrent onset | The dermatosis and malignancy appear concurrently. |

| 2. Parallel course | If the malignancy is successfully treated or recurs, the dermatosis will follow a similar course. |

| 3. Uniformity | A specific malignancy is usually associated with a specific dermatosis. |

| 4. Statistical significance | There is a statistically significant association between the malignancy and the dermatosis based on case-control studies. |

| 5. Genetic basis | A genetic association exists between the dermatosis and the malignancy. |

Nodular vasculitis is a mostly lobular form of panniculitis with associated vasculitis. It is diagnosed at an average age of 56 years2 and presents as painful, erythematous, frequently ulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the posterior aspect of the legs. It has been described in association with tuberculosis,3 autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic diseases, and other infections. Certain medications have also been implicated.

We detected just 2 cases of nodular vasculitis associated with malignancy in our review of the literature. They involved a 63-year-old woman with lung adenocarcinoma4 and a 71-year-old woman with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon diagnosed 2 years after the initial diagnosis of nodular vasculitis.5

Other paraneoplastic syndromes that should be considered in patients with lesions of this type and associated malignancy are other forms of vasculitis and panniculitis and superficial migratory thrombophlebitis.

The most common form of paraneoplastic vasculitis is vasculitis, which is mostly seen in association with hematologic malignancies,6 but also lung, prostate, breast, colon, and kidney cancer.7 It usually manifests as palpable, sometimes ulcerated, purpuric lesions on the lower limbs.

The classic form of paraneoplastic panniculitis is pancreatic panniculitis,8 which is a lobular panniculitis associated with fat necrosis in patients with pancreatic cancer.9 It manifests as ulcerated, erythematous nodules on the upper and lower limbs and is accompanied by fever, weight loss, and elevated amylase and lipase levels.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis is characterized by recurrent episodes of segmental thrombosis in the superficial veins. It usually manifest as painful lower limb nodules, with histology showing vascular occlusion of a medium or large vein in the subcutaneous tissue. It can occur in association with an occult malignancy (Trousseau syndrome), in particular mucinous adenocarcinoma.10

Paraneoplastic nodular vasculitis is treated by addressing the underlying malignancy and prescribing anti-inflammatories, rest, and elevation and compression of the affected limb.3

We have reported, to our knowledge, the first case of paraneoplastic nodular vasculitis associated with metastatic melanoma. Although the association between nodular vasculitis and malignancy is rare, an active search for cancer as a possible trigger should always be conducted in the absence of other plausible causes.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.