Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin condition causing lesions in which high levels of interleukin (IL)-23 and T-helper 17 cells are found. Adalimumab remains the only approved treatment. Guselkumab, an antibody targeting the p19 protein subunit of extracellular IL-23, is approved for the treatment of moderate–severe psoriasis, but evidence on its efficacy in treating HS is limited.

ObjectivesTo assess the effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in treating moderate–severe HS under clinical practice conditions.

MethodsA multicentre retrospective observational study was carried out in 13 Spanish Hospitals including adult HS patients treated with guselkumab within a compassionate use programme (March 2020–March 2022). Data referred to patient demographic and clinical characteristics at treatment initiation (baseline), patient-reported outcomes (Numerical Pain Rating Scale [NPRS] and Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI]), physician scores (International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System [IHS4], HS Physical Global Score [HS-PGA] and Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response [HiSCR]) were recorded at baseline and at 16, 24, and 48 weeks of treatment.

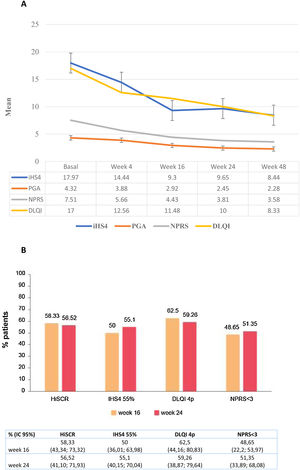

ResultsA total of 69 patients were included. Most (84.10%) had severe HS (Hurley III) and had been diagnosed for over ten years (58.80%). The patients had been subjected to multiple non-biological (mean 3.56) or biological (mean 1.78) therapies, and almost 90% of those treated with biologics had received adalimumab. A significant decrease in IHS4, HS-PGA, NPRS, and DLQI scores was observed from baseline to 48 weeks of guselkumab treatment (all p<0.01). HiSCR was achieved in 58.33% and 56.52% of the patients at 16 and 24 weeks, respectively. Overall, 16 patients discontinued treatment, mostly due to inefficacy (n=7) or loss of efficacy (n=3). No serious adverse events were observed.

ConclusionsOur results indicate that guselkumab may be a safe and effective therapeutic alternative for patients with severe HS that fail to respond to other biologics.

La hidradenitis supurativa (HS) es una situación cutánea crónica que causa lesiones en las que se encuentran altos niveles de interleucina (IL)-23 y células TH-17 colaboradoras, siendo adalimumab el único tratamiento aprobado. Guselkumab, un anticuerpo que focaliza la subunidad de la proteína p19 de IL-23 extracelular, ha sido aprobado para tratar la psoriasis de moderada a severa, siendo limitada la evidencia sobre su eficacia en el tratamiento de la HS.

ObjetivosEvaluar la efectividad y seguridad de guselkumab para el tratamiento de la HS de moderada a severa, en condiciones de práctica clínica.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional retrospectivo y multicéntrico en 13 hospitales españoles, que incluyó pacientes adultos de HS tratados con guselkumab, dentro de un programa de uso compasivo (de marzo de 2020 a marzo de 2022). Se registraron al inicio y a las 16, 24 y 48 semanas de tratamiento los datos referentes a las características demográficas y clínicas de los pacientes, los resultados reportados por el paciente (Numerical Pain Rating Scale [NPRS] y Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI]), puntuaciones del facultativo (International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System [IHS4], HS Physical Global Score [HS-PGA] e Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response [HiSCR]).

ResultadosSe incluyó un total de 69 pacientes, de los cuales la mayoría (84,10%) tenían HS severa (Hurley III) y habían sido diagnosticados hacía más de 10 años (58,80%). Dichos pacientes habían sido sometidos a múltiples terapias no biológicas (media 3,56) o biológicas (media 1,78), y casi el 90% de los tratados con biológicos habían recibido adalimumab. Se observó una reducción significativa de las puntuaciones IHS4, HS-PGA, NPRS y DLQI desde el inicio hasta las 48 semanas del tratamiento con guselkumab (total p<0,01). Se logró HiSCR en el 58,33% y el 56,52% de los pacientes, a las 16 y 24 semanas, respectivamente. A nivel global, 16 pacientes discontinuaron el tratamiento, en su mayoría debido a ineficacia (n=7) o pérdida de eficacia (n=3), no observándose episodios adversos graves.

ConclusionesNuestros resultados indican que guselkumab puede ser una alternativa terapéutica segura y efectiva para los pacientes con HS severa que no responden a otros biológicos.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterised by painful recurrent nodules, abscesses, pus-discharging sinus tracts/fistulas, and scarring.1 Patients are greatly affected by severe pain, movement restrictions, and the foul odour of secretions.1 Genetic and environmental factors drive immune activation and cell infiltration, resulting in excessive and protracted inflammation.1,2 To date, the management of HS relies on antibiotics or antiinflammatory treatment, though adalimumab is the only therapeutic agent approved for HS treatment by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).1,2 Adalimumab is a human anti-tumour necrosis factor antibody shown to achieve Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR), improve quality of life (QoL) and reduces the number and duration of flares, with a predictable tolerability profile.1,2 Considering the impact of HS upon patient life and the limited number of available treatments, there is an unmet need for efficacious and safe therapies for this disease.

HS skin lesions were shown to be infiltrated with macrophages expressing increased levels of interleukin (IL)-23, a major driver of chronic inflammation that governs the maturation of T-helper 17 (Th17) cells,1,3 which are known producers of cytokines that trigger massive inflammation and autoimmunity.4 The IL-23/Th17 axis is implicated in the pathogenesis of autoinflammatory disorders such as HS, psoriasis, and Crohn's disease.4,5 Guselkumab, an approved treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis, is a human immunoglobulin G1 λ monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, preventing intracellular signalling with activation and production of cytokines.6 Considering the key role of the IL-23/Th17 signalling axis in HS, guselkumab might be an adequate treatment alternative for the disease, but evidence on its efficacy treating HS comes from single case reports or case series including less than ten patients.7–11 A randomised phase 2 study evaluating guselkumab in moderate–severe HS was terminated at week 16, as no statistically significant differences in efficacy were found versus placebo.12 Based on this, we assessed the effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in treating moderate–severe HS in patients in the context of compassionate use of the drug in Spain.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patientsA multicentre retrospective observational study involving adult HS patients treated with guselkumab in clinical practice was conducted at 13 Spanish hospitals from March 2020 to March 2022. The patients received guselkumab through compassionate use.

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by an independent ethics committee.

The primary endpoint was the effectiveness of guselkumab in terms of the change in the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4) and Hidradenitis Suppurativa-Physician Global Assessment (HS-PGA) achieved after 16, 24, and 48 weeks of treatment, and the percentage of patients achieving HiSCR at 16 and 24 weeks. We also analysed the change in QoL through DLQI and the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS); we calculated the percentage of patients achieving a reduction in DLQI≥4 points (considered a Minimum Clinically Important Difference [MCID] in DLQI)13 and an NPRS score<3 points at 16 and 24 weeks. The incidence of adverse events (AEs) was also assessed.

Statistical analysisMeasures of central tendency and dispersion were used to describe continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. The change in IHS4, HS-PGA, NPRS, and DLQI scores between baseline and 4, 16, 24, or 48 treatment weeks was determined using a Student's t-test. Bonferroni correction was used to reduce type I error.

The clinical characteristics associated with the attainment of HiSCR, 55% reduction of iHS4 (IHS4-55), and MCID in DLQI at 16 and 24 weeks were analysed using bivariate logistic regression models. All analyses were performed using the SAS© version 9.4 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA).

ResultsA total of 69 HS patients were included in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients at baseline. The mean age was 44 years, and 50.7% were male. Nearly 60% of the patients had been diagnosed with HS for over ten years. Most patients had severe HS (Hurley stage III, 84.1%), an inflammatory phenotype (61.8%), and a mean of 4.3 affected areas. Overall, 47.5% of the patients experienced more than 12 HS flare-ups yearly. They had been treated previously with an average of 1.8 biologics, mainly adalimumab (88.2%), ustekinumab (33.8%), and infliximab (29.4%). The patients had undergone an average of 3.4 surgeries.

Baseline demographic and clinical patients’ characteristics.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| N | 69 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 44.59 (14.2) |

| Sex,n(%) | |

| Men | 35 (50.7%) |

| Women | 34 (49.3%) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.8 (7.6) |

| Data related to HS | |

| Family history of HS, n (%) | 20 (29.9) |

| Clinical history of acne, n (%) | 28 (40.6) |

| Time since diagnosis years,n(%)a | |

| <5 | 13 (19.1) |

| 5–10 | 15 (22.1) |

| >10 | 40 (59.8) |

| Hurley staging,n(%) | |

| I | 1 (1.5) |

| II | 10 (14.5) |

| III | 58 (84.1) |

| Phenotype,n(%) | |

| Inflammatory | 42 (61.8) |

| Follicular | 3 (4.4) |

| Mixed | 23 (33.8) |

| Affected body areas, mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.1) |

| Lesions, mean (SD) | |

| Inflammatory nodules | 3 (3.2) |

| Abscesses | 2.5 (2.3) |

| Draining sinus tracts/fistulas | 2.6 (2.1) |

| Total number of lesions | 8.1 (5.5) |

| Annual number of flare-ups>12,n(%) | 29 (47.5) |

| Prior treatment for HS | |

| No. of previous treatments, mean (SD) | |

| Biological | 1.8 (1.1) |

| Non-biological | 3.6 (2.6) |

| Previous biological treatments, n (%) | |

| Adalimumab | 60 (88.2) |

| Ustekinumab | 23 (33.8) |

| Infliximab | 20 (29.4) |

| Othersb | 17 (24.9) |

| Number of previous surgeries, mean (SD) | 3.35 (3.47) |

| Previous surgeries,n(%) | |

| Deroofing | 19 (28.8) |

| Simple excision | 40 (60.6) |

| Wide excision | 27 (41.5) |

Treatment with guselkumab and combined therapies are summarised in Table 2. Most patients received guselkumab 100mg (66.2%) at baseline, week 4, and then every eight weeks. Most (69%) patients also received other systemic therapies such as oral antibiotics, mainly doxycycline (42.9%), metformin (19.0%), and dapsone (10.5%).

Guselkumab posology and concomitant medication for HS.

| Treatment | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Guselkumab posology,n(%) | |

| 100mg at baseline, w4 and every 8 weeks | 45 (66.2) |

| 100mg every 4 weeks | 20 (29.4) |

| Others | 3 (4.4) |

| Concomitant medication,n(%) | 40 (69.0) |

| Antibiotics | |

| Doxycycline | 12 (42.9) |

| Others | 16 (57.1) |

| Corticosteroids infiltration | 19 (32.8) |

| Metformin | 11 (19.0) |

| Dapsone | 6 (10.5) |

| Colchicine | 1 (1.8) |

| Hormonal contraceptives | 5 (8.9) |

A significant decrease in IHS4, HS-PGA, NPRS, and DLQI scores from baseline was observed at week 16 (all p<0.0001), at week 24 (all p<0.0001) and at week 48 (all p<0.0001) (Fig. 1a). The achievement of HiSCR, IHS4-55, MCID in DLQI (a reduction in DLQI≥4 points), and an NPRS score<3 was recorded in 58.3%, 50%, 62.5%, and 48.7% of the patients at week 16 week, and in 56.5%, 55.1%, 59.3%, and 51.4% at week 24, respectively (Fig. 1b). A statistically significant association was found between guselkumab dose of 100mg/4 weeks and HiSCR achievement (OR=0.15; 95% CI: 0.04–0.56; p=0.004) at week16 but not at week 24. The possibility of a decrease in DLQI≥4 points (MCDI) at week 16 was lower in male patients (OR=0.11; 95% CI: 0.02–0.58; p=0.009) and those who had received a higher number of biologics (OR=0.29; 95% CI: 0.09–0.88; p=0.029).With regards to the pain, NPRS<3 points was significantly more difficult to achieve in patients with a higher number of biological treatments administered (OR=0.34; 95% CI: 0.13–0.84; p=0.020) at 16 weeks and with the number of fistulas (OR=0.68; 95% CI: 0.74–0.99; p=0.046) at 24 weeks. A greater number of body areas affected was associated with less probability to obtain a NPRS<3 at both 16 (OR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.44–0.96; p=0.033) and 24 weeks (OR=0.67; 95% CI: 0.44–0.99; p=0.049) (Table 3).

Factors significantly associated with achieve HiSCR, iHS4 55% and fail to decrease in DLQI≥4 points or obtain a NPRS<3 points.

| Week 16 | Week 24 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | |

| HiSCR | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.079 | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 0.499 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) |

| Sex (men) | 0.558 | 0.71 (0.22–2.24) | 0.150 | 0.41 (0.12–1.37) |

| BMI | 0.506 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.901 | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) |

| Phenotype | ||||

| Follicular vs. mixto | 0.975 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.975 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| Inflammatory vs. mixto | 0.832 | 1.14 (0.32–3.97) | 0.562 | 1.52 (0.41–5.64) |

| Affected body areas | 0.512 | 1.09 (0.82–1.46) | 0.871 | 0.97 (0.69–1.35) |

| Hurley staging | ||||

| I vs. III | 0.986 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.986 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| II vs. III | 0.281 | 2.57 (0.46–14.35) | 0.366 | 2.25 (0.38–13.06) |

| No. of previous treatments | 0.088 | 0.53 (0.25–1.09) | 0.646 | 1.15 (0.63–2.09) |

| No. of previous surgeries | 0.055 | 1.26 (0.99–1.61) | 0.068 | 1.32 (0.97–1.80) |

| No. inflammatory nodules | 0.217 | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 0.949 | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) |

| No. abscesses | 0.931 | 0.98 (0.76–1.27) | 0.728 | 1.04 (0.81–1.35) |

| No. draining sinus tracts/fistulas | 0.121 | 0.79 (0.59–1.069 | 0.506 | 0.91 (0.68–1.20) |

| Total number of lesions | 0.901 | 1.01 (0.90–1.12) | 0.870 | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <5 years vs. >10 years | 0.113 | 4.00 (0.71–22.28) | 0.786 | 1.25 (0.25–6.28) |

| 5–10 years vs. >10 years | 0.587 | 1.50 (0.34–6.49) | 0.697 | 0.75 (0.17–3.19) |

| Guselkumab posology (100mg/4 weeks) | 0.004 | 0.15 (0.04–0.56) | 0.932 | 0.95 (0.36–2.51) |

| iHS4 55 | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.497 | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.191 | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) |

| Sex (men) | 1.000 | 1.00 (0.35–2.85) | 0.127 | 0.41 (0.12–1.29) |

| BMI | 0.198 | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 0.222 | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) |

| Phenotype | ||||

| Follicular vs. mixto | 0.975 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.975 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| Inflammatory vs. mixto | 0.382 | 0.60 (0.19–1.88) | 0.912 | 0.93 (0.27–3.21) |

| Affected body areas | 1.000 | 1.00 (0.77–1.28) | 0.990 | 1.00 (0.75–1.32) |

| Hurley staging | ||||

| I vs. III | 0.985 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.985 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| II vs. III | 0.955 | 1.04 (0.23–4.67) | 0.331 | 2.38 (0.41–13.71) |

| No. of previous treatments | 0.114 | 0.60 (0.32–1.12) | 0.577 | 1.18 (0.65–2.14) |

| No. of previous surgeries | 0.057 | 1.21 (0.99–1.49) | 0.106 | 1.23 (0.95–1.58) |

| No. inflammatory nodules | 0.509 | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 0.328 | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) |

| No. abscesses | 0.532 | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | 0.785 | 0.96 (0.76–1.23) |

| No. draining sinus tracts/fistulas | 0.096 | 0.79 (0.61–1.04) | 0.085 | 0.77 (0.58–1.03) |

| Total number of lesions | 0.596 | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.721 | 0.97 (0.87–1.09) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <5 years vs. >10 years | 0.182 | 2.57 (0.64–10.30) | 0.594 | 0.51 (0.12–2.18) |

| 5–10 years vs. >10 years | 0.711 | 1.28 (0.34–4.86) | 0.634 | 1.52 (0.32–7.29) |

| Guselkumab regimen (100mg/4weeks) | 0.361 | 0.64 (0.25–1.64) | 0.822 | 0.89 (0.35–2.29) |

| Fail to decrease DLQI≥4 points | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.913 | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 0.241 | 0.93 (0.90–1.02) |

| Sex (men) | 0.009 | 0.11 (0.02–0.58) | 0.052 | 0.19 (0.03–1.01) |

| BMI | 0.865 | 0.98 (0.86–1.13) | 0.212 | 1.11 (0.94–1.31) |

| Phenotype | ||||

| Follicular vs. mixto | 0.981 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.979 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| Inflammatory vs. mixto | 0.296 | 0.45 (0.10–2.01) | 0.951 | 0.95 (0.20–4.35) |

| Affected body areas | 0.315 | 0.84 (0.61–1.17) | 0.137 | 0.71 80.46–1.11) |

| Hurley staging | ||||

| I vs. III | 0.979 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.979 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| II vs. III | 0.364 | 2.93 (0.28–30.01) | 0.907 | 1.12 (0.15–8.20) |

| No. of previous treatments | 0.029 | 0.29 (0.09–0.88) | 0.672 | 0.82 (0.34–1.98) |

| No. of previous surgeries | 0.629 | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) | 0.151 | 1.26 (0.91–1.74) |

| No. inflammatory nodules | 0.876 | 0.98 (0.81–1.21) | 0.490 | 1.12 (0.81–1.55) |

| No. abscesses | 0.565 | 0.91 (0.67–1.23) | 0.100 | 1.51 (0.92–2.46) |

| No. draining sinus tracts/fistulas | 0.537 | 0.89 (0.63–1.26) | 0.407 | 0.84 (0.56–1.26) |

| Total number of lesions | 0.546 | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.302 | 1.12 (0.89–1.41) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <5 years vs. >10 years | 0.937 | 0.92 (0.12–6.78) | 0.970 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| 5–10 years vs. >10 years | 0.813 | 1.23 (0.18–8.33) | 0.415 | 2.72 (0.24–30.66) |

| Guselkumab regimen (100mg/4weeks) | 0.738 | 0.80 (0.21–2.93) | 0.158 | 0.35 (0.08–1.49) |

| Fail to obtain NPRS pain<3 | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.364 | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 0.109 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) |

| Sex (men) | 0.693 | 1.28 (0.36–4.49) | 0.256 | 0.46 (0.12–1.74) |

| BMI | 0.164 | 0.93 (80.84–1.03) | 0.298 | 0.95 (0.86–1.04) |

| Phenotype | ||||

| Follicular vs. mixto | 0.966 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.968 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| Inflammatory vs. mixto | 0.164 | 4.78 (0.52–43.69) | 0.680 | 1.50 (0.21–10.30) |

| Affected body areas | 0.033 | 0.65 (0.44–0.96) | 0.049 | 0.67 (0.44–0.99) |

| Hurley staging | ||||

| I vs. III | 0.978 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) | 0.977 | 1.00 (0.01–10.00) |

| II vs. III | 0.226 | 2.78 (0.53–14.66) | 0.061 | 8.50 (0.90–80.02) |

| No. of previous treatments | 0.020 | 0.34 (0.13–0.84) | 0.761 | 0.88 (0.41–1.91) |

| No. of previous surgeries | 0.536 | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 0.845 | 0.98 (0.80–1.18) |

| No. inflammatory nodules | 0.191 | 0.86 (0.71–1.07) | 0.398 | 0.91 (0.72–1.13) |

| No. abscesses | 0.632 | 0.93 (0.69–1.24) | 0.179 | 0.80 (0.58–1.10) |

| No. draining sinus tracts/fistulas | 0.079 | 0.71 (0.48–1.04) | 0.046 | 0.68 (0.74–0.99) |

| Total number of lesions | 0.107 | 0.89 (0.77–1.02) | 0.064 | 0.86 (0.74–1.01) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||

| <5 years vs. >10 years | 0.075 | 1.08 (0.86–19.22) | 0.191 | 3.00 (0.57–15.61) |

| 5–10 years vs. >10 years | 0.085 | 1.25 (0.81–22.13) | 0.287 | 2.50 (0.46–13.52) |

| Guselkumab regimen (100mg/4weeks) | 0.593 | 0.68 (0.17–2.72) | 0.925 | 0.94 (0.31–2.92) |

Bold values are those with statistical significance.

Guselkumab was discontinued in 16 patients (23.2%), following a mean treatment time of 7.81 months (SD±5.06). The most common cause of discontinuation was inefficacy or loss of efficacy (62.5%). Only 39 patients (56.5%) reached 48 weeks of treatment with guselkumab. No serious AEs were observed (Table 4).

DiscussionOur study suggests that the treatment of moderate to severe HS with guselkumab leads to significant reductions in HS severity (IHS4, HiSCR) and pain (NPRS), with an improvement of patient QoL (DLQI). Although patient characteristics and disease severity did not appear to be associated with the attainment of IHS4-55, an association was found between a larger number of fistulas and affected areas and failure to achieve a reduction of ≥4 points in DLQI (MCID) at 16 weeks and the attainment of NPRS<3 at 16 and 24 weeks. Males and those who had previously received more biologics also appeared less likely to reach MCID in DLQI (decrease of ≥4 points) at 16 weeks. Patients treated with guselkumab 100mg every four weeks had less chances of attaining HiSCR at 16 weeks but not at 24 weeks. These patients might have had more severe HS, requiring adjustments of the treatment regimen and length, though this was not evaluated.

Data on the effectiveness of guselkumab in treating HS is scarce and based on a small number of reports involving few or single patients. In a Spanish study, four HS patients that failed to respond to other biologics were treated with guselkumab 100mg every four weeks, showing improvement of the disease at 12 weeks in two cases, with moderate reduction of the IHS4, NPRS, and DLQI scores, and with no changes in HS-PGA or significant AEs.11 Guselkumab 100mg at baseline, week 4, and then every eight weeks (the most common regimen used in our series) also led to HS improvement in 5/8 patients in another study. However, three patients showed no improvement in the first 2–4 months, suggesting that more time might be needed to reach maximum efficacy.8

Guselkumab has been shown to be effective in treating HS patients with other comorbidities such as Crohn's disease.7,14 Interestingly, guselkumab was also reported to reduce HS lesions and resolve a paradoxical psoriasiform reaction and sacroiliitis following adalimumab treatment for HS in a patient who experienced a decrease in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and, in whom a further decrease in HS lesions was observed over ten months of follow-up.15 Together with these results, our findings suggest that guselkumab may be an effective and safe therapeutic option for moderate–severe HS, ameliorating other concomitant conditions and providing an alternative treatment for patients failing to respond to adalimumab. This is the first study to report a large series of HS patients treated with guselkumab.

Our study has limitations, including its retrospective nature. Despite a large number of enrolled individuals, only 39 patients remained on treatment after 48 weeks. Improvements in the therapeutic scheme and patient follow-up might be needed to further mitigate lesions, especially in severe cases; additional studies are needed to address this issue.

In conclusion, our results suggest that guselkumab may be a safe and effective therapeutic alternative for patients with moderate–severe HS failing to respond to other therapies.

Conflict of interestThe authors meet the authorship criteria recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and did not receive payment related to the development of this article.

R. Rivera-Díaz has the following conflict of interests: received honoraria for participating in advisory boards and clinical trials from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and UCB; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Almirall, Janssen, Novartis, and Eli Lilly; and her institution received an ultrasonography from Abbvie. B. Díaz Ley received payment or honoraria for lectures and educational events from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer Sandoz, and UCB; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbvie, Almirall, Cantabria Labs, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and participated as member of Advisory Boards for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. E. Vilarrasa received payment or honoraria for lectures and educational events from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer Sandoz, and UCB; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbvie, Almirall, Cantabria Labs, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and participated as member of Advisory Boards for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. A. Martorell received payment or honoraria for lectures and educational events from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbvie, Almirall, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and participated as member of Advisory Boards for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. The rest of the authors report no conflict of interest.

To all patients who agree to used their data to improve our knowledge about this disease.