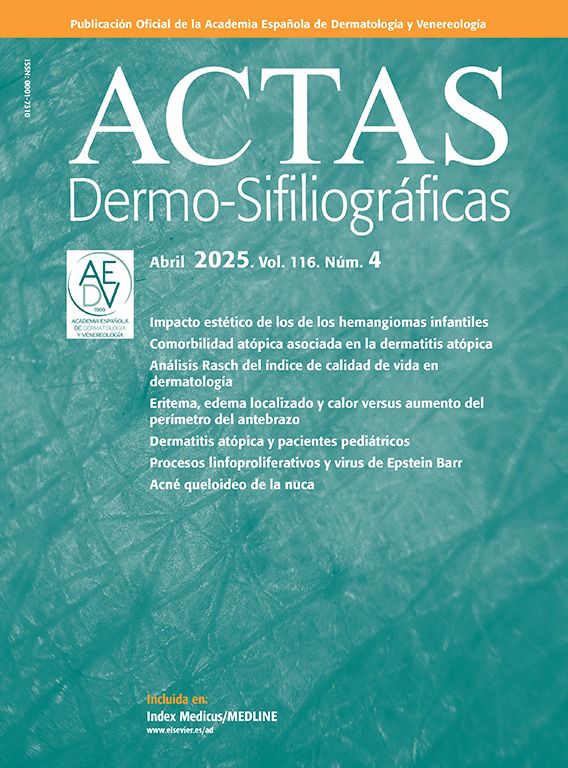

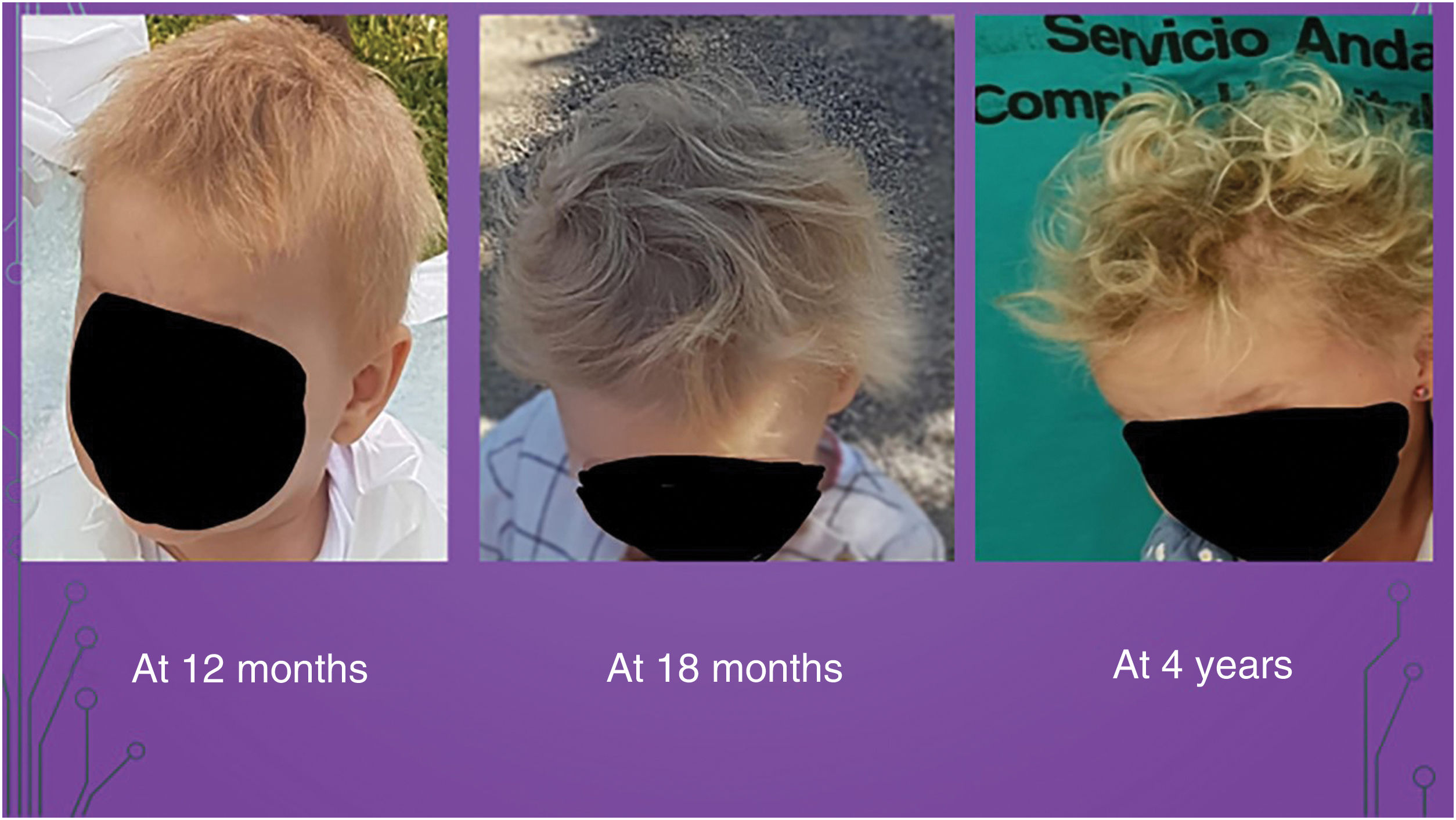

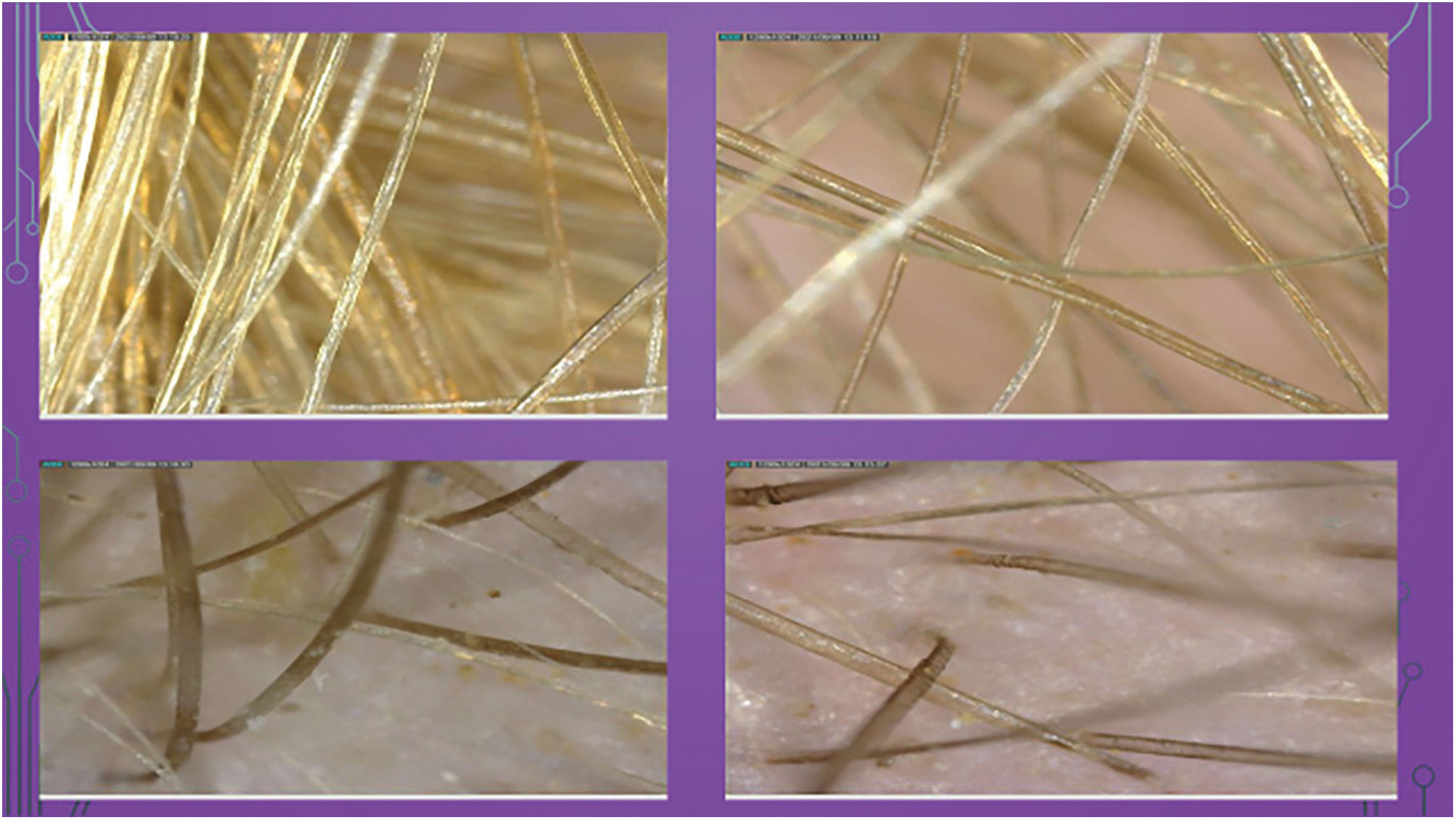

A 2-year-old girl was referred to our clinic for showing short, coarse, and always unkempt hair. The alteration had begun within the first few months of life and progressively worsened (Fig. 11). No personal or family pathological history was reported. Psychomotor development was normal, and no other skeletal, ophthalmological, otic, or dental disorders were found. On examination, the scalp showed low density of blonde, dry, dull, coarse, and disordered hair. Eyebrows and eyelashes were unremarkable. Trichoscopy revealed the presence of hairs with a longitudinal groove or channel emerging from the scalp in different directions (Fig. 22). Blood tests were normal. Electron microscopy (EM) showed grooved hair shafts with a triangular shape in cross-section (Fig. 33). Genetic study confirmed a mutation in the PADI3 gene, showing 2 altered nucleotides c.335t>a (p.leu 112his) and c881c>t (p.ala 294val), confirming the diagnosis of uncombable hair syndrome type 1. Oral biotin and zinc pyrithione shampoo were prescribed. In subsequent follow-ups, the girl showed increased hair density, longer hair, and it remained unkempt.

Uncombable hair syndrome (UHS) was first described by Dupré et al. in 1973, and that same year, Stroud and Mehregan reported a similar case in a 6-year-old girl. However, the phenotype had been recognized much earlier and gained notoriety with the famous literary character “Struwwelpeter” (“Shock-headed Peter”) from the children's book published by the German physician Heinrich Hoffmann back in 1845. It has also been called “glass wool hair” due to its appearance, while “pili trianguli et canaliculi” refers to its appearance under electron microscopy (EM).1 To date, a total of 127 cases have been reported.2 Both sporadic and autosomal recessive cases have been described, and it can be an isolated phenotype or part of a syndrome. Clinically, it shows as silvery, blonde, or straw-colored hair, dry, frizzy, with a characteristic shine due to light reflection on the grooved hair. It deviates from the scalp in different directions and is impossible to comb. It typically affects scalp hair, while eyebrows, eyelashes, and other hairy areas are rarely affected. Localized variants in the frontal or occipital regions have been reported. Three subtypes have been described based on the mutated gene: type 1 (OMIM 191480) in the PADI3 gene (peptidyl arginine deiminase III); type 2 (OMIM 617251) in the TGM3 gene (transglutaminase 3); and type 3 (OMIM 617252) in the TCHH gene (trichohyalin).3,7 The constant finding is the “pili canaliculi”, which can also be observed in the loose anagen hair syndrome, androgenetic alopecia, alopecia areata, scarring alopecia, and other ectodermal dysplasias. It has been described in association with skin (63%), nail (28%), and dental (25%) disorders and, occasionally, with dysmorphic, neuropsychiatric and developmental, ophthalmic, otic, and cardiopulmonary disorders.2 Trichoscopy shows well-implanted terminal hairs going in different directions, some even overlapping and crossing, without any signs of perifollicular inflammation.4,6 In EM, longitudinal channels are observed, and in cross-section, they may appear triangular, kidney-shaped, quadrangular, or irregular.1,6 In general, UHS tends to improve with the onset of puberty. Treatments have included biotin supplements,4–6 with favorable results in some patients. The use of zinc pyrithione shampoos may also be beneficial in this condition by producing a rebound effect in the production of scalp oil, providing some conditioning effect, and improving the extremely dry appearance of the hair.7 Although UHS usually presents as an isolated sign on the scalp, its occasional coexistence with other disorders makes it highly advisable to rule them out and, whenever possible, to conduct genetic studies to narrow down the different variants that may exist.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.