Rosacea fulminans is a severe skin disease of the face that is characterized by the sudden onset of papules, pustules, and nodules. Pregnancy is considered a potential trigger. Serious complications can develop in pregnant women if the disease is not diagnosed and treated early. We report a new case of rosacea fulminans in a pregnant woman and analyze the epidemiologic and therapeutic characteristics and severe complications reported in this group of patients.

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman who was 14 weeks pregnant came to the clinic with an extensive outbreak of pustules on an erythematous–edematous base, with no comedones. The lesions were located on the cheeks and forehead (Fig. 1) and accompanied by low-grade fever. No acneiform lesions were observed at other sites. The patient denied having taken new medication and recent exposure to sunlight. Bacterial culture of the pustules was negative, and no significant laboratory abnormalities were recorded.

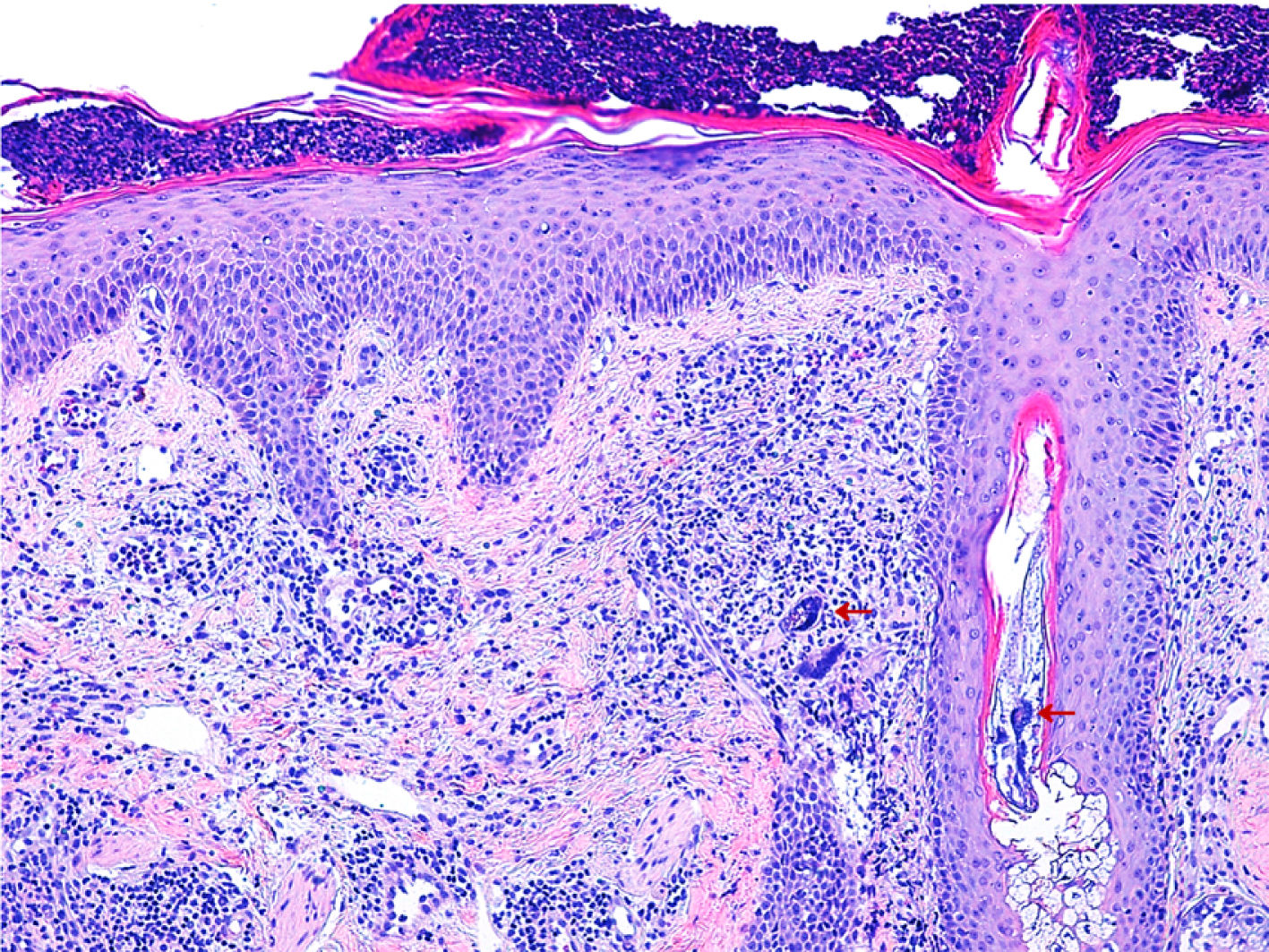

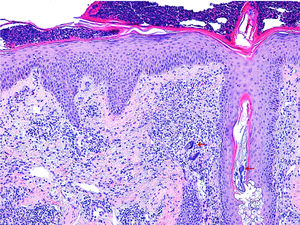

Histology (Fig. 2) revealed reactive epidermal hyperplasia, with a collection of intracorneal neutrophils and infundibular dilatation of the hair follicle. The dermis was remarkable for the presence of vascular ectasia and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. An abundance of Demodex folliculorum was also observed. Together with the symptoms, these findings were compatible with rosacea fulminans. The patient was given erythromycin 500mg/8h for 3 weeks in combination with topical metronidazole and hydrocortisone. Topical metronidazole was subsequently maintained for 3 months, leading to almost complete resolution of the lesions.

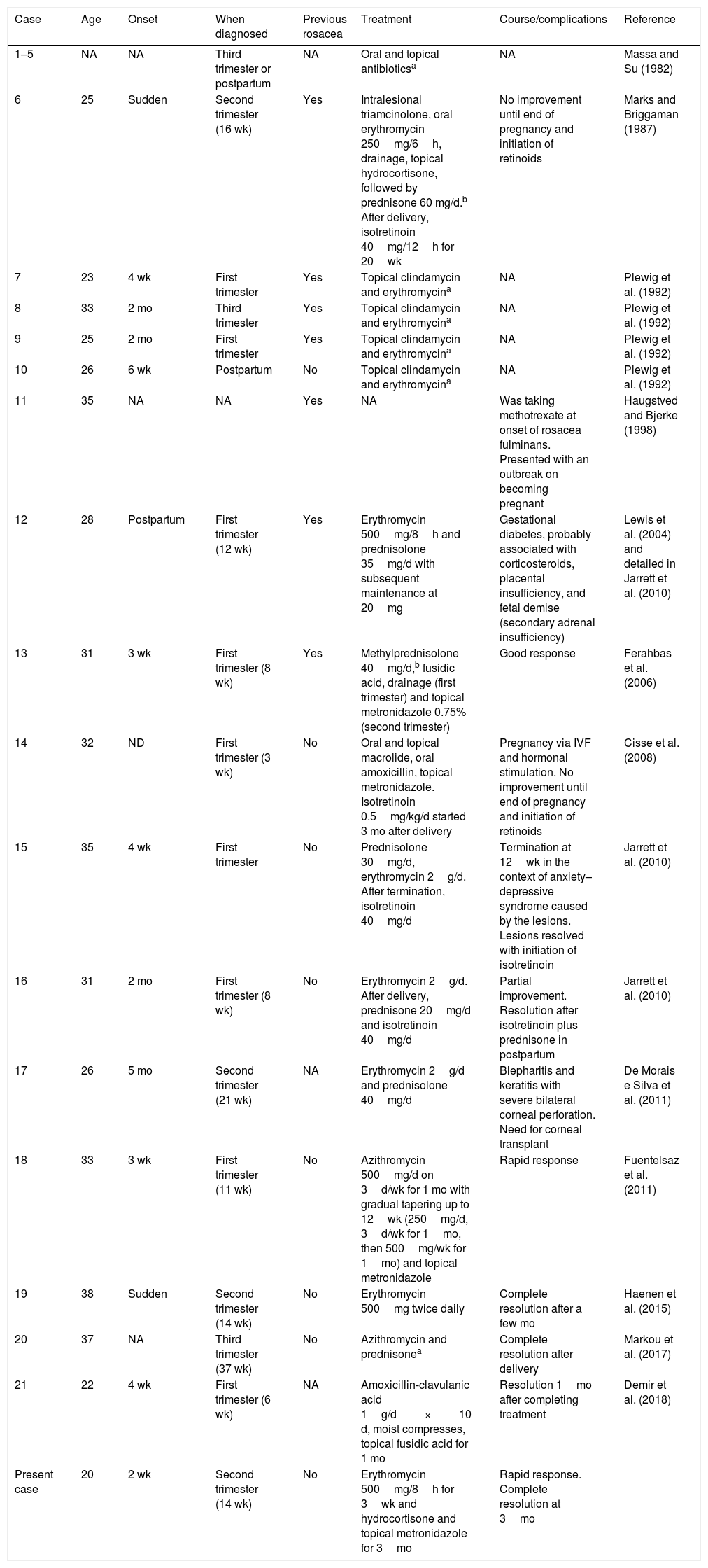

To date, we have identified 21 cases of rosacea fulminans during pregnancy (Table 1).1–13 The median age was 31 years (range, 20–38 years), and most patients were diagnosed during the first trimester (43%) owing to the appearance of lesions a few weeks earlier. In 32% of cases, the patient reported a history of rosacea before becoming pregnant. Oral antibiotics were the most widely prescribed option (95%), with macrolides being the first choice in 68% of patients. Almost one-third of patients (32%) also received systemic corticosteroids that were subsequently tapered, and 18% required isotretinoin after labor owing to lack of response to their previous treatment. Topical treatment was administered in 68% of cases, mainly with metronidazole, clindamycin, and erythromycin. The severe complications reported include a case of fetal demise owing to the adverse effects of corticosteroids (secondary adrenal insufficiency),5 induced abortion owing to major anxiety-depression syndrome,8 and a case of bilateral corneal perforation requiring a corneal transplant.9 There are no reports of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies.

Epidemiologic and Therapeutic Characteristics and Complications in Cases of Rosacea Fulminans During Pregnancy.

| Case | Age | Onset | When diagnosed | Previous rosacea | Treatment | Course/complications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–5 | NA | NA | Third trimester or postpartum | NA | Oral and topical antibioticsa | NA | Massa and Su (1982) |

| 6 | 25 | Sudden | Second trimester (16 wk) | Yes | Intralesional triamcinolone, oral erythromycin 250mg/6h, drainage, topical hydrocortisone, followed by prednisone 60 mg/d.b After delivery, isotretinoin 40mg/12h for 20wk | No improvement until end of pregnancy and initiation of retinoids | Marks and Briggaman (1987) |

| 7 | 23 | 4 wk | First trimester | Yes | Topical clindamycin and erythromycina | NA | Plewig et al. (1992) |

| 8 | 33 | 2 mo | Third trimester | Yes | Topical clindamycin and erythromycina | NA | Plewig et al. (1992) |

| 9 | 25 | 2 mo | First trimester | Yes | Topical clindamycin and erythromycina | NA | Plewig et al. (1992) |

| 10 | 26 | 6 wk | Postpartum | No | Topical clindamycin and erythromycina | NA | Plewig et al. (1992) |

| 11 | 35 | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Was taking methotrexate at onset of rosacea fulminans. Presented with an outbreak on becoming pregnant | Haugstved and Bjerke (1998) |

| 12 | 28 | Postpartum | First trimester (12 wk) | Yes | Erythromycin 500mg/8h and prednisolone 35mg/d with subsequent maintenance at 20mg | Gestational diabetes, probably associated with corticosteroids, placental insufficiency, and fetal demise (secondary adrenal insufficiency) | Lewis et al. (2004) and detailed in Jarrett et al. (2010) |

| 13 | 31 | 3 wk | First trimester (8 wk) | Yes | Methylprednisolone 40mg/d,b fusidic acid, drainage (first trimester) and topical metronidazole 0.75% (second trimester) | Good response | Ferahbas et al. (2006) |

| 14 | 32 | ND | First trimester (3 wk) | No | Oral and topical macrolide, oral amoxicillin, topical metronidazole. Isotretinoin 0.5mg/kg/d started 3 mo after delivery | Pregnancy via IVF and hormonal stimulation. No improvement until end of pregnancy and initiation of retinoids | Cisse et al. (2008) |

| 15 | 35 | 4 wk | First trimester | No | Prednisolone 30mg/d, erythromycin 2g/d. After termination, isotretinoin 40mg/d | Termination at 12wk in the context of anxiety–depressive syndrome caused by the lesions. Lesions resolved with initiation of isotretinoin | Jarrett et al. (2010) |

| 16 | 31 | 2 mo | First trimester (8 wk) | No | Erythromycin 2g/d. After delivery, prednisone 20mg/d and isotretinoin 40mg/d | Partial improvement. Resolution after isotretinoin plus prednisone in postpartum | Jarrett et al. (2010) |

| 17 | 26 | 5 mo | Second trimester (21 wk) | NA | Erythromycin 2g/d and prednisolone 40mg/d | Blepharitis and keratitis with severe bilateral corneal perforation. Need for corneal transplant | De Morais e Silva et al. (2011) |

| 18 | 33 | 3 wk | First trimester (11 wk) | No | Azithromycin 500mg/d on 3d/wk for 1 mo with gradual tapering up to 12wk (250mg/d, 3d/wk for 1mo, then 500mg/wk for 1mo) and topical metronidazole | Rapid response | Fuentelsaz et al. (2011) |

| 19 | 38 | Sudden | Second trimester (14 wk) | No | Erythromycin 500mg twice daily | Complete resolution after a few mo | Haenen et al. (2015) |

| 20 | 37 | NA | Third trimester (37 wk) | No | Azithromycin and prednisonea | Complete resolution after delivery | Markou et al. (2017) |

| 21 | 22 | 4 wk | First trimester (6 wk) | NA | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1g/d×10 d, moist compresses, topical fusidic acid for 1 mo | Resolution 1mo after completing treatment | Demir et al. (2018) |

| Present case | 20 | 2 wk | Second trimester (14 wk) | No | Erythromycin 500mg/8h for 3wk and hydrocortisone and topical metronidazole for 3mo | Rapid response. Complete resolution at 3mo |

Abbreviations: IVF, in vitro fertilization; NA, not available.

Rosacea fulminans is a severe facial dermatosis of uncertain origin. Hormonal changes during pregnancy could be a trigger. Very extended lesions have been reported in pregnant women, as have profound and irreversible eye involvement9 and a psychiatric condition triggered by the onset of lesions.8 Given the degree of involvement of rosacea fulminans, systemic treatment is often necessary. However, commonly used drugs, such as retinoids and tetracyclines, are contraindicated during pregnancy. Therefore, oral macrolides such as erythromycin and azithromycin are the safest and most effective option in this situation. More evidence is available for erythromycin, although findings for the effectiveness of azithromycin in rosacea are favorable, showing a more comfortable dosing regimen and fewer adverse effects.10 Topical antibiotics should also be added owing to their anti-inflammatory effects. Systemic corticosteroids may prove to be necessary, although they can cause delayed intrauterine growth, gestational diabetes, and hypertension, as well as secondary adrenal insufficiency, which can lead to fetal demise.5,8

Considering the cases reviewed, we propose the following therapeutic approach: first-line therapy with oral macrolides combined with topical clindamycin or metronidazole, and second-line therapy with addition of topical and systemic corticosteroids (doses up to 0.5mg/kg/d).

In conclusion, rosacea fulminans is a severe skin disease that can develop during pregnancy. Affected patients should be diagnosed early to avoid progression to extended lesions. Thus, we can decrease the possibility of potentially severe complications by reducing the need for treatment with systemic corticosteroids.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.