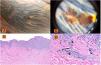

Currently, decorative tattoos are widespread, with a prevalence greater than 25% in the United States in individuals aged between 18 and 50 years, and a slightly lower prevalence in Europe and Australia.1 Depending on the series, in the last 40 years, between 18 and 50 cases of malignant melanoma have been reported after tattoos for decorative purposes or for radiotherapy (Fig. 1A and B).1,2 The first case report dates from 1938, but it was not until 1969 that Kirsch described a melanoma with axillary lymph node metastasis in an arm where the patient had had a tattoo 27 years previously.3

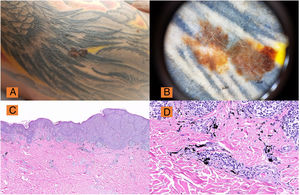

A, Pigmented lesion with abnormal ABCD clinical criteria on the right arm over a tattoo. B, Dermatoscopy (DermLite® DL3) ×10: Melanoma lesion with areas of regression, broken and atypical pigmented network, asymmetry and manifest polychromasia, confirmed histologically as superficial-spreading melanoma, Breslow depth 0.25 mm. C, H&E, ×2: Low-magnification view of superficial-spreading melanoma with pagetoid distribution. D, Melan A: Detail of melanoma staining and pigment in the superficial dermis.

Currently, we are seeing an increase in the number of cases of melanoma diagnosed in patients who had been tattooed previously. Although this association may merely be a coincidence, it is important to reflect on a couple of points of importance given their diagnostic and therapeutic ramifications.

First, from the pathogenic point of view, 4 factors have been suggested that could explain this relationship: A, trauma associated with the tattoo; B, local catabolites produced after introducing the ink; C, photoreaction secondary to introducing the ink in the dermis and hypodermis; and D, the chronic inflammatory process that persists after tattooing.

Second, it is important to reflect on why melanoma appears on tattoos that are predominantly black and blue, whereas nonmelanoma skin cancer appears on reddish pigments, although to date no causal relationship has been established.4 We should remember that pigments based on mercury, cobalt sulfate, and other soluble salts are classed as group 2B agents of possible human carcinogens, whereas cadmium and its derivatives belong to group I of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (carcinogenic for humans), and that the composition of tattoo inks is not internationally regulated or standardized.2 It is important to note that the use of mercury pigments and other heavy metal pigments that were used in the past is now forbidden for any type of pigment production, although they may be present as impurities. Thus, nowadays, metal pigments have been replaced mainly by synthetic azoic and polycyclic pigments.

Klujer and Koljonen,1 who in 2012 published an interesting review on the association between skin cancer and tattoos, remind us that any potential link would be multifactorial. Trauma is not considered a direct pathogenic factor for melanoma; moreover, tattoos are often done on skin with extensive intermittent exposure to sunlight, and this factor clearly is associated with malignant melanoma.5

Finally, it is important to note the complications derived from dermatoscopy6 and diagnostic techniques such as selective lymph node biopsy. The presence of pigment in regional lymph nodes may be responsible for diagnostic errors, and these should be recognized by the dermatology surgeon and consultation with the pathologist is essential in all cases.

In conclusion, we should be alert to this new reality in our clinics to avoid delays in diagnosis of melanoma on tattoos, as delay is associated with worse prognosis for the patient, even though the cases published to date have not established a causal relationship and the presence of such melanomas may be coincidental.

Please cite this article as: Ródenas-Herranz T, Linares-Gonzalez L, Aneiros-Fernández J, Ruiz-Villaverde R. FR- Melanoma y tatuajes. Una asociación controvertida. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:518–519.