Cultural, socio-demographic and environmental factors such as tropical climate and exposure to sun could have an impact on the incidence or clinical course of psoriasis. Here we describe the main clinical aspects of psoriasis in Brazilian patients and also investigate whether any particular feature can distinguish the disease occurring in Brazil from that occurring in other countries.

Material and methodsWe recorded the clinical features of 151 psoriasis patients seen in a Brazilian public dermatological care unit between 2006 and 2008.

ResultsMales and females were similarly affected. The reported races were as follows: whites, 47 cases (41.6%), interracial individuals (mixed race), 42 cases (37.2%) and blacks, 24 cases (21.2%). Chronic plaque-type psoriasis was the most prevalent clinical form (110 cases, 72.8%) followed by palm and sole involvement (21 cases, 13.9%).

ConclusionsWe demonstrated that psoriasis in these Brazilian subjects was similar to that observed in subjects from other countries, but interracial and black populations were affected as much as whites. Considering the high rate of interracial populations among Brazilians we cannot exclude the possibility that Afro-descendants may have inherited Caucasian genes associated with psoriasis. Poor socio-economic conditions of Afro-descendants can limit their possibilities of receiving adequate treatments, impairing their health-related quality of life.

Los factores culturales, sociodemográficos y ambientales tales como el clima tropical o la exposición solar pueden tener un impacto en la incidencia o el curso clínico de la psoriasis. En este artículo describimos los principales aspectos clínicos de la psoriasis en pacientes brasileños e investigamos si existe alguna característica que permita distinguir la enfermedad que ocurre en Brasil de la que se encuentra en otros países.

Material y métodosSe recogieron las características clínicas de 151 pacientes con psoriasis evaluados en un centro dermatológico público de Brasil entre 2006 y 2008.

ResultadosLos hombres y las mujeres estaban afectados de forma similar. La frecuencia de afectación según la raza era la siguiente: blancos 47 casos (41,6%), mestizos 42 casos (37,2%) y negros 24 casos (21,2%). Las formas clínicas más prevalentes fueron la psoriasis crónica en placas (110 casos, 72,8%) seguida de la psoriasis palmoplantar (21 casos, 13,9%).

ConclusionesDemostramos que la psoriasis en estos sujetos brasileños es similar a la que se observa en sujetos de otros países, pero los mestizos y los negros están afectados tanto como los blancos. Teniendo en cuenta la elevada proporción de población mestiza entre los brasileños, no podemos descartar la posibilidad de que los descendientes africanos hayan podido heredar los genes caucásicos asociados a la psoriasis. Las pobres condiciones socioeconómicas de los descendientes africanos pueden limitar sus posibilidades para recibir tratamientos adecuados, lo que altera su calidad de vida.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects skin and joints1. Estimates of prevalence are relatively high, varying from 0.5 to 4.6%, depending on the geographic location, but especially affecting Caucasians1,2. The etiology of the disease is unknown, but genetic predisposition and environmental factors can influence the occurrence and severity of the disease1,3,4. Epidermal proliferation is a key feature of psoriasis although immune mediated mechanisms are crucial for maintaining the inflammatory lesions5,6. Plaque psoriasis is the most frequent clinical form of the disease, affecting up to 80% of patients3,4. The onset of symptoms can be divided into two periods, teenagers (type 1) or individuals in the fifth decade of life (type 2), without distinct sex prevalence7. Most studies concerning epidemiology and clinical aspects of psoriasis focus on European and North American populations. However, very few reports address the epidemiological and clinical features of psoriasis in developing regions such as South America8,9. In Brazil, miscegenation, besides the typical tropical climate and sun exposure, can have a beneficial impact such as delayed onset and progression of psoriatic lesions. Here we describe the main clinical aspects of psoriasis in Brazilian patients that were evaluated in a public dermatological outpatient care unit in Rio de Janeiro state. We also investigate whether any particular feature can distinguish the disease occurring among Brazilian patients from that occurring among patients from other countries.

MethodologyWe carried out a retrospective analysis of selected records of 151 patients that have been seen at the public dermatological outpatient care unit of the Hospital Gaffrée-Guinle/UNIRIO from April 2006 to September 2008. Demographic data such as age, sex, race, and geographic origin were considered. Patients were submitted to dermatological examination, and clinical aspects such as duration of illness before diagnosis and lesion features (clinical form, distribution and shape of lesions) were also investigated. All patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the diagnosis of psoriasis, which were based on established clinical parameters1 and histopathological criteria6. The severity of psoriasis was assessed. To measure the activity and severity of psoriasis we used the Physician Global Assessment (PGA). The PGA is one of the most commonly used tools for assessing psoriasis activity and for following clinical response to treatment. There are two main forms of assessment completed by a physician: a static and a dynamic one, in which the physician assesses the global improvement compared to baseline; the latter is hardly reproducible and is based on the observer's memory, so the static assessment has been generally made to assess overall psoriasis, using a score between 0 and 6 (0=clear [no signs of psoriasis], 1=almost clear [minimal], 2=mild [slight plaque elevation, scaling and/or erythema], 3=mild to moderate [intermediate between mild and moderate], 4=moderate [moderate plaque elevation, scaling and/or erythema], 5=moderate to severe [marked plaque elevation, scaling and/or erythema] and 6=severe [very marked plaque elevation, scaling and/or erythema])10–18. In this period, the new dermatological outpatients were evaluated to estimate the prevalence of psoriasis in the Department of Dermatology. Prevalence is usually defined as the proportion of individuals in a given population with a disease in a specified time period.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Escola de Medicina e Cirurgia (UNIRIO, MEC, Brazil).

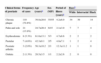

ResultsThe new dermatological outpatients in the general clinic were analyzed for skin color and were reported as follows: interracial individuals (mixed race): 61.2%, whites: 37%, blacks: 1.9%, and 78.2% of the patients were primarily from Rio de Janeiro state. Psoriasis was responsible for 5.2% (95% confidence interval: 3.1–7.6%) of consultations at the Department of Dermatology in this period of 17 months. Among the 151 psoriatic patients selected for the study, the disease was equally distributed between males (71 cases, 46.3%) and females (80 cases, 53.6%). The mean age±standard deviation was 42.1±20.9 years (median 44 years, ranging from 3 to 83 years) for males and 35.8±20.8 years (median 36 years; ranging from 3 to 80 years) for females. Patients aged between 51–60 years (19.9%), 41–50 years (17.6%) and 31–40% (14%) accounted for the majority of cases, followed by patients aged between 0–10 years (16.2%). The period in which women reached medical care for the first consultation after the onset of symptoms was more precocious (3.6±5.4 years; median 1 year, ranging from one month to 25 years) than for men (4.7±6.9 years; median 2 years, ranging from two months to 33 years). One hundred thirteen cases were analyzed for skin color and were reported as follows: whites, 47 cases (41.6%), interracial individuals (mixed race), 42 cases (37.2%) and blacks, 24 (21.2%). No significant difference in terms of race was observed among males and females (Table 1). The most frequent clinical forms of psoriasis are recorded (Table 1), but chronic plaque psoriasis was the most prevalent (110 cases, 72.8%). Indeed, palm and sole involvement accounted for 13.9% of cases. The mean age of chronic plaque patients at the onset of symptoms was 39.8±20.6 years, with no sex differences. The majority of patients were also interracial individuals or blacks (66 cases). Patients usually exhibited single lesions (46 in 133 cases), but two (30 in 133 cases) or three lesions (20 in 133 cases) were equally very common. The affected body regions were mainly the scalp (28 cases, 21%), elbows (25 cases, 18.8%), and knees (21 cases, 15.8%). Other locations such as nails, face, back, abdomen, and chest were referred in less than 1% of cases. Only two cases of psoriatic arthritis, and no cases of inverse psoriasis or generalized pustular psoriasis were found. One hundred twenty two cases were analyzed for the severity of psoriasis (PGA score) and are reported as follows: 0 (none of the patients), 1 (9 in 122 cases), 2 (32 in 122 cases), 3 (33 in 122 cases), 4 (21 in 122 cases), 5 (13 in 122 cases) and 6 (14 in 122 cases). The reported associated diseases were hypertension (9), atopy (7), HIV/AIDS (2), hepatitis (2), diabetes mellitus (3), and hyperthyroidism (1). Only five patients referred a family history of psoriasis.

Main patients’ demographic characteristics related to clinical forms of psoriasis observed in a Brazilian population

| Clinical forms of psoriasis | Frequency of cases | Age (years)a | Sex (M/F) | Period of illness (years)a | Raceb | ||

| White | Interracial | Black | |||||

| Chronic plaque | 110 (72.8%) | 39.8±20.6 | 55/55 | 4.2±6.0 | 34 | 30 | 14 |

| Palm and sole | 21 (13.9%) | 24.7±20.4 | 6/15 | 2.1±3.0 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Erythrodermic | 8 (5.3%) | 61.0±13.1 | 5/3 | 4.7±8.6 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Pustular | 7 (4.6%) | 42.3±9.1 | 2/5 | 4.8±7.1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 3 (2.0%) | 56.3±10.2 | 2/1 | 12.3±11.2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Guttata | 2 (1.3%) | 28.5±3.5 | 1/1 | 2.2±2.6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

F: female. M: male.

Psoriasis affects people worldwide1–3; however, cultural, socio-demographic, and environmental factors could have an impact on the incidence or clinical course of the disease in some geographic regions. Here we analyzed psoriasis cases from an outpatient care unit located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. We demonstrated that the clinical form of the disease was similar to that observed in other countries, but interracial and black populations were affected as much as whites. No difference regarding gender was observed in the present study, even after taking into account different races. Considering the mean age of the onset of symptoms, our patients were equally distributed into type I and type II7. As expected, chronic plaque psoriasis was the most common clinical presentation with no difference for gender or skin color. Conversely, psoriatic arthritis was rarely reported, probably because these patients were mainly seen by Rheumatology services. Interracial and black subjects did not present a more severe clinical form of the disease, as has been suggested by previous authors19. The low intensity and severity of psoriasis in this sample (PGA score 5 [13 in 122 cases] and 6 [14 in 122 cases]) could be attributed to the tropical climate in Brazil, a country located close to the equator. The country is exposed to high levels of ultraviolet radiation from intense sunlight throughout the year, which leads to a much better prognosis of the disease20,21. In a Colombian study, 18.6% of 86 patients presented severe psoriasis22.

In our study, blacks comprised 18% of patients seen in our care unit, and our results indicate that psoriasis also affects an Afro-descendant population. Such percentage is high considering the official data showing that the Brazilian population consists of 38.2% of interracial individuals and 5.9% of blacks23, which include Afro-descendants. These data are surprising as psoriasis is classically considered a Caucasian disease that affects less than 0.1% of Asians and is considered rare among Africans1–3,24. Note that two Latin Americans studies led to different findings. Gonzalez et al analyzed 86 patients and reported that race distribution was as follows: interracial individuals (85%), whites (14%) and blacks (1%)22. Trujillo et al analyzed 200 patients and reported the following distribution: interracial individuals (10.5%), whites (85.5%), blacks (3.5%) and unknown (0.5%)20. Yet, population-based studies showed that psoriasis affects a significant fraction of African-Americans, although it was observed a reduction in the prevalence of approximately 52% compared to Caucasians19.

In contrast, whites predominated in a previous Brazilian study, though it also included patients seen in a private dermatology practice9. In this study, we hypothesize that blacks may have inherited Caucasian genes associated with psoriasis25 because of the high number of interracial populations in Brazil. In fact, this hypothesis is consistent with the literature. Green reported that psoriasis among indigenous Australians of “full-blood” descent may be rare or non-existent; minimal cases haved been reported among Aborigines, and psoriasis diagnoses were associated with Aboriginal people of mixed descent26. Further research indicated that the condition appeared to be relatively uncommon among Nigerians and Mongolians, and more common among Kenyans and people from the Faroe Islands27–29. It is worth noting that the different methodology employed in research design, such as population-based research compared with hospital-based research, makes it difficult to conclude whether these differences were indeed a result of racial variation30.

Indeed, other factors such as behavior and environmental conditions can also influence the development of the disease24,31. Perhaps a major component of regional variation in the frequency, severity and morbidity of psoriasis is climate variation. A population-based study reported a seasonal variation in psoriasis diagnoses, in which over 65% of the cases were diagnosed in winter and spring, as opposed to approximately 30% of cases diagnosed in summer and autumn32. Farber and Nail reported that almost 90% of the respondents indicated that cold weather made their psoriasis worse, approximately 80% claimed that hot weather made their psoriasis better, and 80% stated that sunlight made their psoriasis better33. With respect to geographical or climatic features, an author recorded the highest prevalence level of the disease in the central area of Spain, whose weather is drier and colder than in the northern and southern/Mediterranean regions of Spain34.

In country-specific studies, the estimated prevalence of psoriasis ranges from 0% in Australian Aborigines and Andean Indians to 11.8% in the inhabitants of Kazakhstan (an Arctic region of the Soviet Union)35. More comprehensive studies reported that the prevalence of psoriasis was 1.4% in Spain34, 1.5% in the United Kingdom36 and 2.9% in South Africa37 and Italy38. The present study analyzed the epidemiology of psoriasis, but the prevalence of psoriasis (5.2%) was estimated for new dermatological outpatients in a limited clinical setting, with a small population. Therefore, it does not reflect the true prevalence of this specific disease in the Brazilian population. We believe that larger population-based studies should provide a broader picture of the incidence and/or prevalence of psoriasis in Brazil. Trujillo et al reported that psoriasis represents 6% of the dermatologic consultations in Cuba20. This large number is justified because the health system in Cuba20, as well as in Brazil39, is free, allowing easy access to data concerning the entire population.

Although this study was not designed to estimate the race prevalence of psoriasis, our results suggest that this disease is common in the African-descendant Brazilian population. Different ethnic backgrounds can mirror the health-related quality of life, and African-Brazilians are more likely to have a low social status compared to that of Caucasians40. Indeed, poor socio-economic factors can limit African-Brazilian patients’ possibilities of receiving adequate treatments, and such factors can have an effect on these patients’ health-related quality of life. Accordingly, these results should be considered in health care policy making in Brazil, particularly when developing policies in public health programs for psoriasis patients.

Conflict of interestAuthors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We are grateful to Dr R. Vieira-Gonçalves for the valuable suggestions, to Sonia Maria Ramos Vasconcelos for the linguistic revision and to the clinical staff of the Serviço de Dermatologia-HUGG/UNIRIO. C. Porto-Ferreira is a graduate student at Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Médicas, FCM-UERJ. A.M. Da-Cruz is a research fellow from FAPERJ.