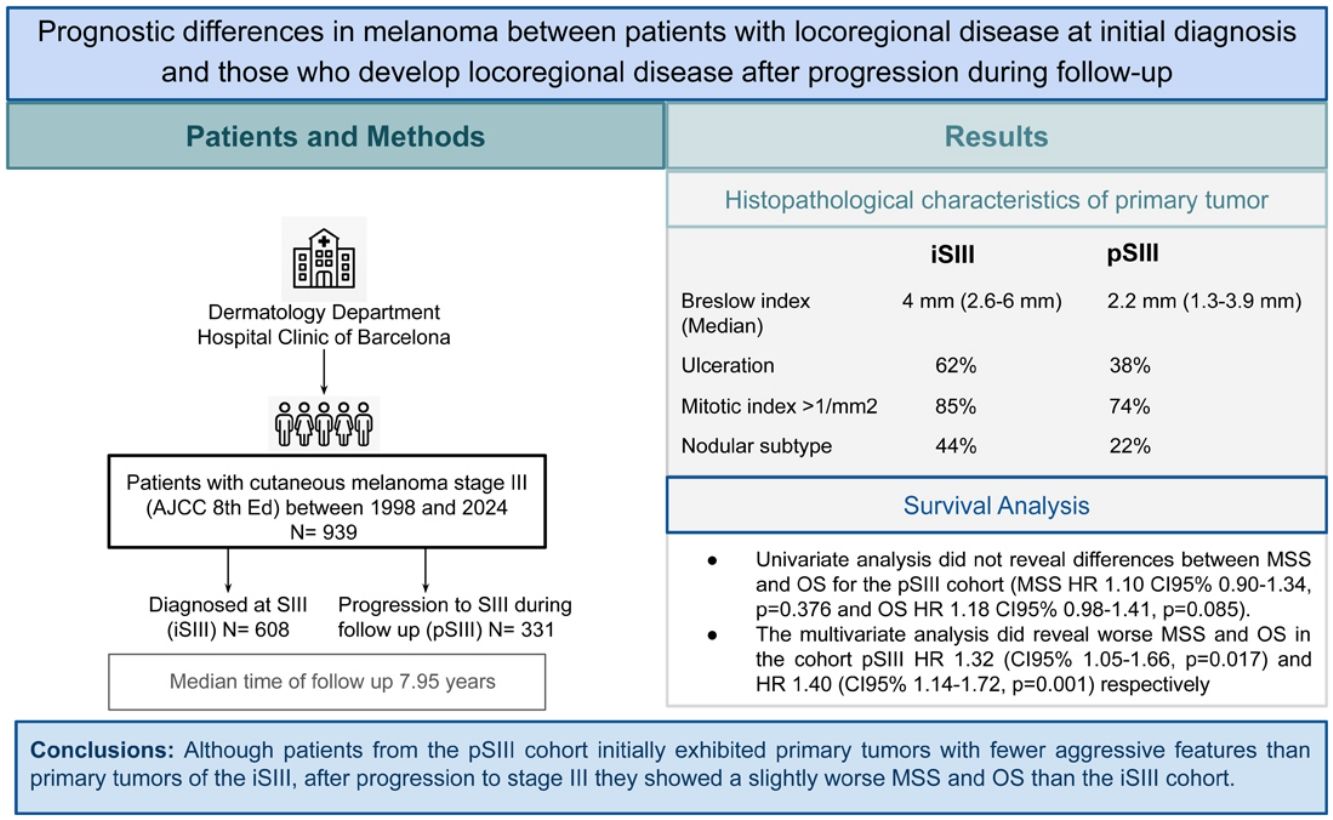

Stage III cutaneous melanoma affects a heterogeneous group of patients. AJCC staging subdivides stage III according to micro- or macroscopic lymph nodes or in transit/cutaneous locoregional metastasis, without accounting for whether locoregional involvement is identified at diagnosis or post-progression. Information on potential divergent behavior among these subgroups is lacking.

The aim of the study is to analyze the differences in survival of melanoma patients with stages IIIB–IIID at diagnosis vs stages IIIB–IIID after relapse.

Materials and methodWe conducted a cohort study with patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma between 1998 and 2022. Patients in stage III (AJCC 8th) were identified and divided into 2 cohorts: initial stages IIIB-D (iSIII) and stages IIIB-D during progression (pSIII). We analyzed the clinical and histopathological characteristics and performed Cox regression analysis for melanoma specific survival (MSS) and overall survival (OS).

ResultsOf the 939 patients included, 608 had incident stage III (iSIII) melanoma and 331 had progressive stage III (pSIII) melanoma. Primary melanomas in the iSIII cohort showed greater Breslow thickness and higher mitotic indices and were more frequently ulcerated than those in the pSIII group (p<.001). Multivariable Cox regression analysis showed a slightly worse MSS and OS for patients in the pSIII cohort with an HR of 1.32 (95%CI, 1.05–1.66; p=0.017) and an HR of 1.40 (95%CI, 1.14–1.72; p=0.001) respectively.

ConclusionsAlthough patients from the pSIII cohort initially exhibited primary tumors with fewer aggressive features than primary tumors of the iSIII, after progression to stage III they showed a slightly worse MSS and OS than the iSIII cohort.

Cutaneous melanoma is an aggressive neoplasm responsible for 75–90% of skin cancer-related deaths.1 Survival rates vary widely, depending primarily on the systemic therapy availability, with a 5-year survival rate>90% for patients with localized disease (stages I–II), 20–70% for those with locoregional involvement (stage III) and 9–28% for those with distant metastatic disease (stage IV).2–4

One third of melanoma patients will experience recurrence or metastases due to disease progression. Patients with earlier stages at diagnosis have a longer latency period for progression and a higher proportion of locoregional metastases while patients initially diagnosed with stage III tend to develop earlier distant metastases.5

Stage III cutaneous melanoma patients are a heterogeneous group with locoregional cutaneous and/or lymph nodal disease. Although the AJCC staging system2 subdivides stage III melanoma into categories based on microscopic lymph node metastasis (A), macroscopic lymph node metastasis (B), or in-transit/cutaneous metastasis (C), it does not account for whether locoregional involvement is identified at initial diagnosis or develops during follow-up.

Although approval of adjuvant therapy for patients with high risk stage III has improved relapse-free survival (RFS), approximately 25% will relapse within a year.6

Most clinical trials of adjuvant therapy have focused on initial stage III melanoma; however, patients eligible for this treatment include patients with initial stage III and patients with stage III after progression from stages I or II.7–12 There is a lack of information on whether these subgroups could show different behavior.

The aim of this study is to analyze the basal tumor characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with initial stage III melanoma and patients with stage III after progression.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a cohort study. Patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma who attended the Dermatology Department of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona from 1998 to 2022 were included. Patients with stage III melanoma were categorized into 2 cohorts: initial stage III (iSIII), comprising patients diagnosed with stage III disease at presentation, and progressive stage III (pSIII), comprising patients initially diagnosed with stage I or II disease who progressed to stage III during follow-up.

Because this study included only patients with clinically evident metastases, those with nodal micrometastases (stage IIIA) were excluded, as micrometastases are not observed in the progressive cohort (pSIII). Patients with lymph node involvement from an unknown primary cutaneous melanoma were also excluded.

To standardize the stage at diagnosis of patients included in the study, they were re-staged following the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual,2 treated, and monitorized based on the standard clinical practice guidelines.13

The dependent variables included were Melanoma Specific Survival (MSS) defined as the time from diagnosis of stage III to death caused by the disease and overall survival (OS) defined as the time from the diagnosis of stage III to death from any cause. Patients without such an event were censored at the date of the last follow-up visit.

Categorical independent variables included were:

- -

Sex defined as biological sex at birth: male/female.

- -

Age at the time of diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma.

- -

TNM stage: defined as AJCC 8th edition staging at diagnosis in cohort iSIII and, at diagnosis and after progression to stage III in cohort pSIII.

- -

Location of primary melanoma defined as site of the body where the primary melanoma was located: head and neck/trunk/upper limbs/lower limbs/acral/mucosa.

- -

Histologic subtype defined as histologic classification of the primary melanoma: superficial spreading/nodular/lentigo maligna/acral/others.

- -

Breslow thickness: measured in millimeters from the granular layer to the deepest tumor cells; in case of ulcerated tumors it is measured from the base of the ulcer to the deepest tumor cells.

- -

Ulceration: absence of an intact epidermis overlying a major portion of the primary melanoma based on microscopic examination of the histologic sections.

- -

Regression: histologic area of the melanoma where the tumor retreats or disappears to be progressively replaced by fibrosis with presence of melanophages and variable degrees of inflammation; regression absent/regression<50% of the tumor/regression>50% of the tumor area.

- -

Mitotic index: No. of mitotic figures counted over an area of 1mm2.

Missing data were treated as missing completely at random and excluded from the analysis. In cases of multiple primary melanomas, only the lesion with the worst histologic prognosis was considered for outcome assessment to minimize immortal time bias.

The present study was conducted following the recommendations of the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) guidelines.14

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR). Pearson's Chi-squared test and trend test were used for categorical and ordinal variables, respectively. The Wilcoxon rank sum test compared independent continuous variables.

We determined the cohort's median follow-up using the reverse Kaplan–Meier estimator and the ‘prodlim’ package utilizing both the ‘prodlim’ and ‘Hist’ functions (v 2024.6.25) in R. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to assess survival differences in MSS and OS. The ‘survfit’ function from the ‘survival’ package (v 3.7.0) was employed for curve calculation, and visualization was achieved using the ‘survminer’ package (v 0.4.9). To determine the statistical significance of outcome differences among groups, a log-rank test was used. To explore the factors independently associated with MSS and OS, we employed a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model using the ‘coxph’ function in the survival package (v 3.7.0).

The statistical analyses were conducted using the R computing environment (v R version 4.3.2 (2023-10-31)), together with RStudio (v 2024.9.0.375). To determine statistical significance, a two-sided p-value threshold of <0.05 was set.

ResultsIn the study period, a total of 939 cases of cutaneous melanoma stage III were included: 608 in cohort iSIII and 331 in the pSIII. The median follow-up was 7.95 years (IQR, 4.74–11.87).

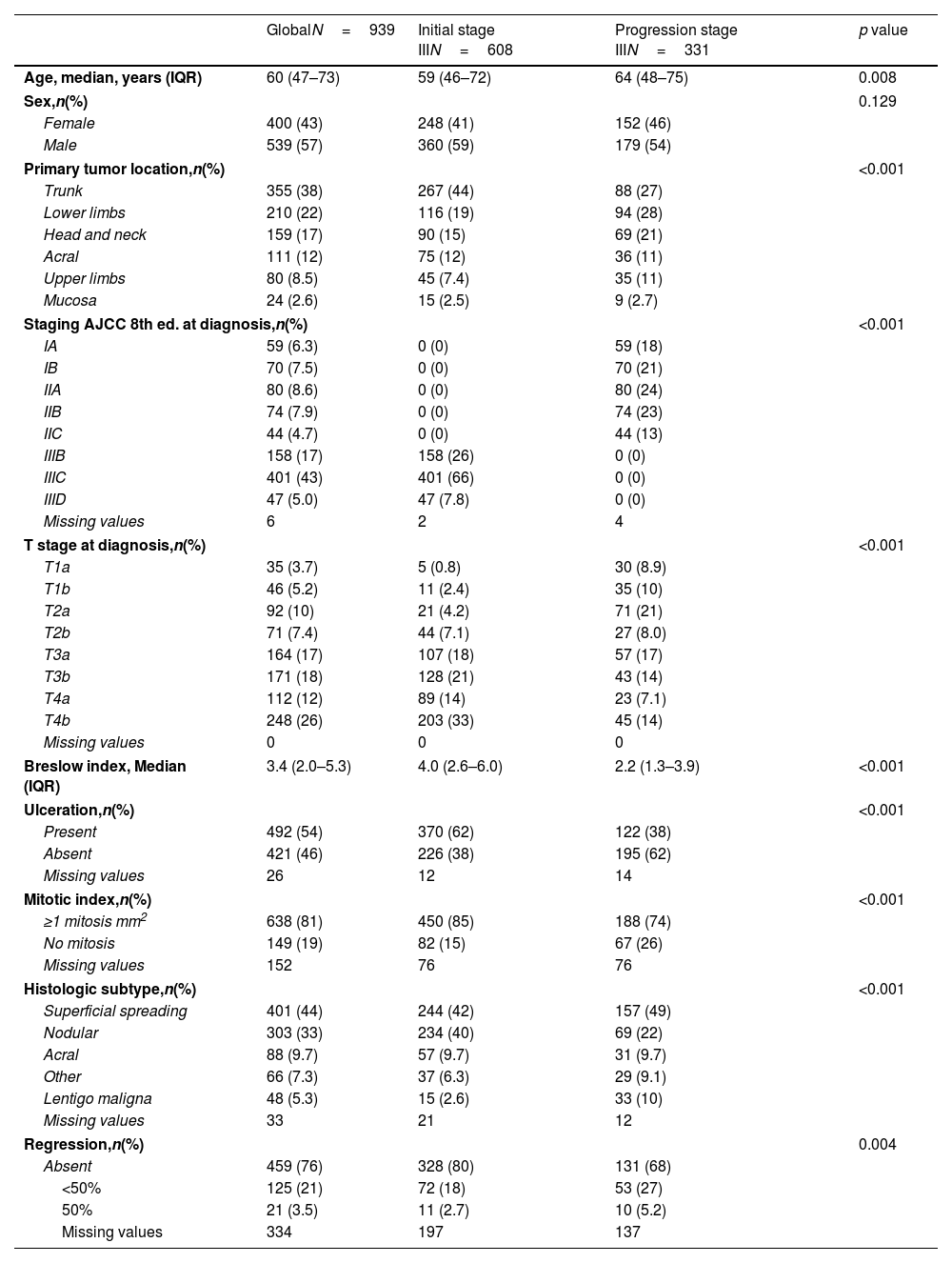

Patients from the iSIII cohort were diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma at younger ages with a median of 59 years [46–72] vs 64 years [48–75] from the pSIII (p=0.008). Men were predominant in both cohorts. The most common locations of the primary tumor were the trunk and lower limbs (Table 1). Most patients from the iSIII cohort were stage IIIC at diagnosis (66%) followed by stage IIIB (26%) while the initial staging of pSIII patients was distributed across stages IIA, IIB and IB (24%, 23% and 21% respectively). Although superficial spreading melanoma was the most frequent subtype, nodular melanoma was significantly more frequent in the iSIII (40% vs 22%; p<0.001). Breslow thickness was higher in the iSIII, with a median of 4mm [2.6–6.0] vs pSIII (median of 2.2mm [1.3–3.9]) (p<0.001). Cutaneous melanomas of the iSIII cohort were more prone to be ulcerated (62% vs 38%; p<0.001) and to have a higher median of mitotic index rates (iSIII 85% MI>1/mm2, pSIII 74% MI>1/mm2; p<0.001). Regression features were absent in most primary melanomas in the iSIII cohort (80%), whereas 32.2% of primary tumors in the pSIII cohort showed regression (p=.004) (Table 1).

Characteristics of the cohorts included in the study.

| GlobalN=939 | Initial stage IIIN=608 | Progression stage IIIN=331 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, years (IQR) | 60 (47–73) | 59 (46–72) | 64 (48–75) | 0.008 |

| Sex,n(%) | 0.129 | |||

| Female | 400 (43) | 248 (41) | 152 (46) | |

| Male | 539 (57) | 360 (59) | 179 (54) | |

| Primary tumor location,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| Trunk | 355 (38) | 267 (44) | 88 (27) | |

| Lower limbs | 210 (22) | 116 (19) | 94 (28) | |

| Head and neck | 159 (17) | 90 (15) | 69 (21) | |

| Acral | 111 (12) | 75 (12) | 36 (11) | |

| Upper limbs | 80 (8.5) | 45 (7.4) | 35 (11) | |

| Mucosa | 24 (2.6) | 15 (2.5) | 9 (2.7) | |

| Staging AJCC 8th ed. at diagnosis,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| IA | 59 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 59 (18) | |

| IB | 70 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 70 (21) | |

| IIA | 80 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 80 (24) | |

| IIB | 74 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 74 (23) | |

| IIC | 44 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 44 (13) | |

| IIIB | 158 (17) | 158 (26) | 0 (0) | |

| IIIC | 401 (43) | 401 (66) | 0 (0) | |

| IIID | 47 (5.0) | 47 (7.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing values | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| T stage at diagnosis,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| T1a | 35 (3.7) | 5 (0.8) | 30 (8.9) | |

| T1b | 46 (5.2) | 11 (2.4) | 35 (10) | |

| T2a | 92 (10) | 21 (4.2) | 71 (21) | |

| T2b | 71 (7.4) | 44 (7.1) | 27 (8.0) | |

| T3a | 164 (17) | 107 (18) | 57 (17) | |

| T3b | 171 (18) | 128 (21) | 43 (14) | |

| T4a | 112 (12) | 89 (14) | 23 (7.1) | |

| T4b | 248 (26) | 203 (33) | 45 (14) | |

| Missing values | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Breslow index, Median (IQR) | 3.4 (2.0–5.3) | 4.0 (2.6–6.0) | 2.2 (1.3–3.9) | <0.001 |

| Ulceration,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| Present | 492 (54) | 370 (62) | 122 (38) | |

| Absent | 421 (46) | 226 (38) | 195 (62) | |

| Missing values | 26 | 12 | 14 | |

| Mitotic index,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥1 mitosis mm2 | 638 (81) | 450 (85) | 188 (74) | |

| No mitosis | 149 (19) | 82 (15) | 67 (26) | |

| Missing values | 152 | 76 | 76 | |

| Histologic subtype,n(%) | <0.001 | |||

| Superficial spreading | 401 (44) | 244 (42) | 157 (49) | |

| Nodular | 303 (33) | 234 (40) | 69 (22) | |

| Acral | 88 (9.7) | 57 (9.7) | 31 (9.7) | |

| Other | 66 (7.3) | 37 (6.3) | 29 (9.1) | |

| Lentigo maligna | 48 (5.3) | 15 (2.6) | 33 (10) | |

| Missing values | 33 | 21 | 12 | |

| Regression,n(%) | 0.004 | |||

| Absent | 459 (76) | 328 (80) | 131 (68) | |

| <50% | 125 (21) | 72 (18) | 53 (27) | |

| 50% | 21 (3.5) | 11 (2.7) | 10 (5.2) | |

| Missing values | 334 | 197 | 137 | |

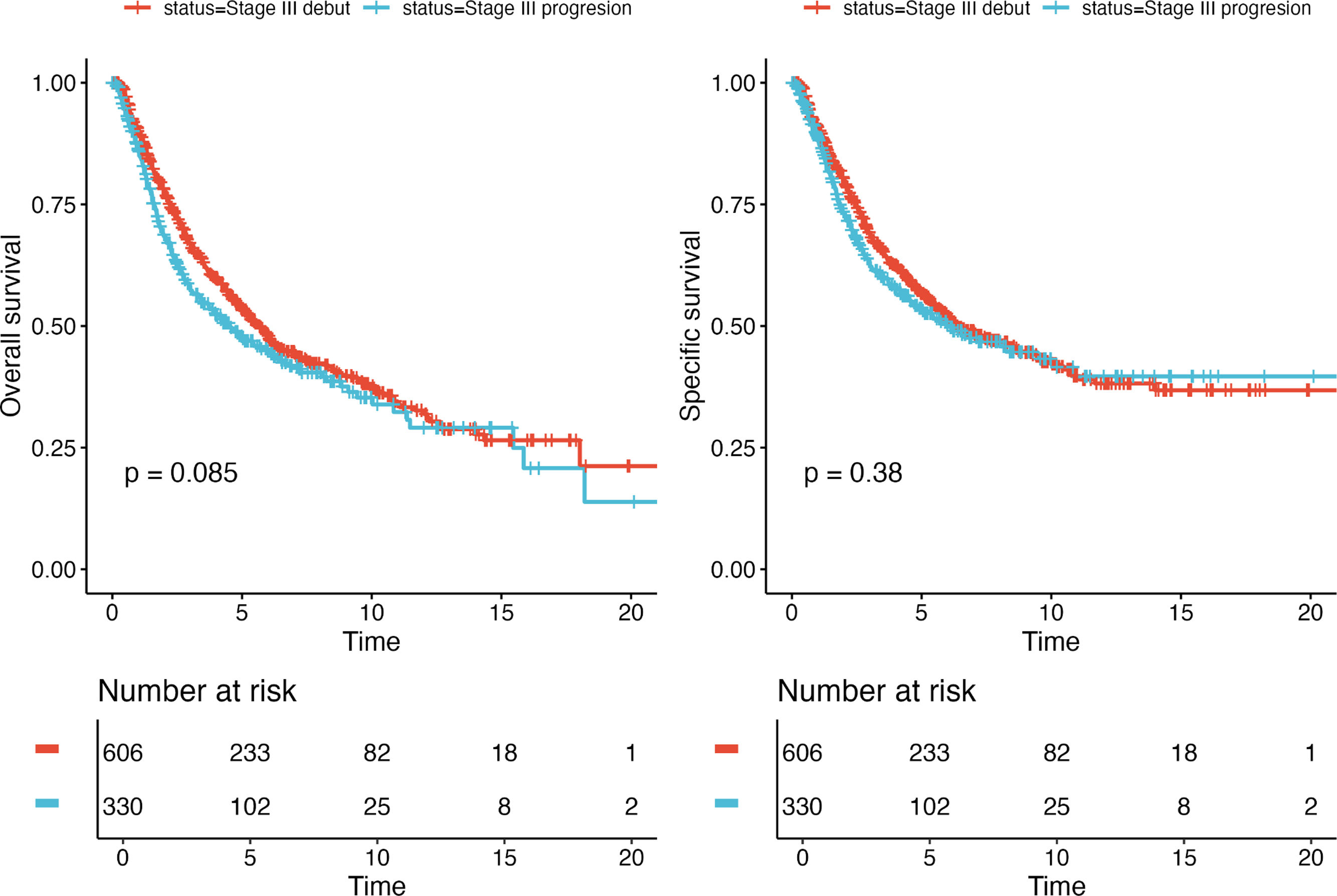

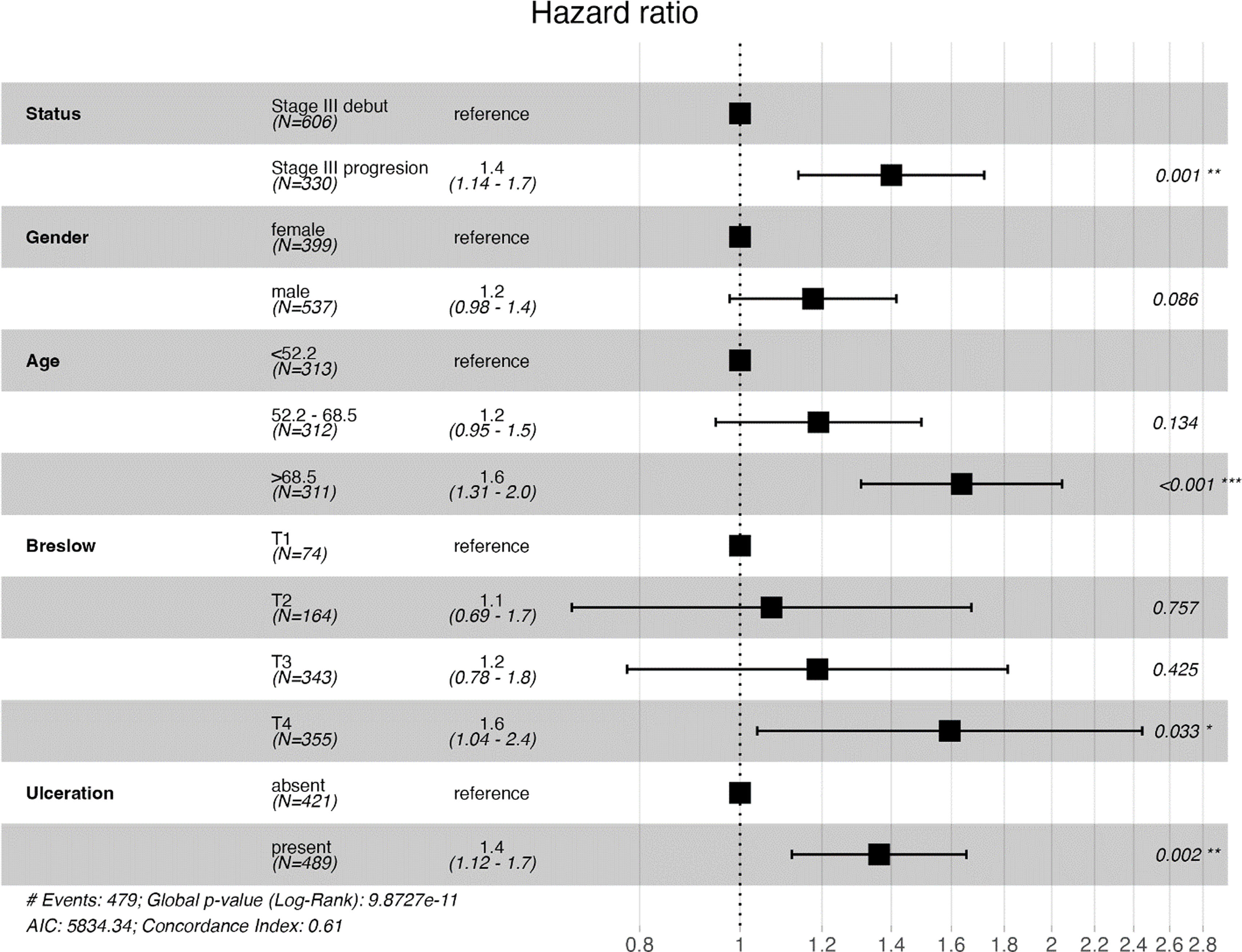

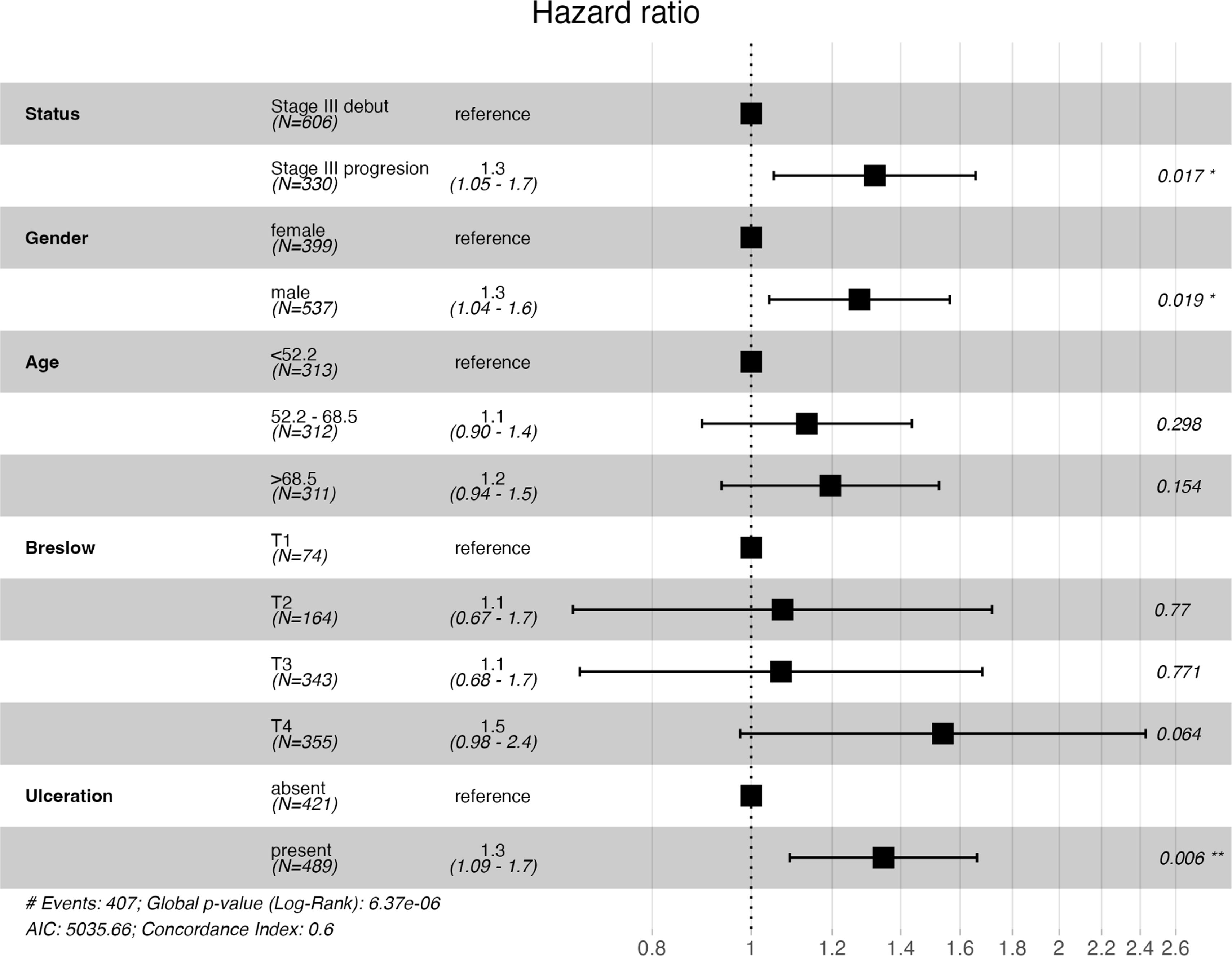

Survival analyses with Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare the iSIII and pSIII cohorts and no significant differences in survival were observed for all survival outcomes (Fig. 1). Additionally, MSS and OS were compared by Cox regression uni-and multivariate models. Univariate analysis did not reveal any differences between MSS and OS for the pSIII cohort (MSS HR, 1.10; 95%CI, 0.90–1.34; p=0.376; and OS HR 1.18, 95%CI, 0.98–1.41; p=0.085). However, the multivariate analysis revealed worse MSS and OS in the cohort pSIII HR 1.32 (95%CI, 1.05–1.66; p=0.017) and HR 1.40 (95%CI, 1.14–1.72; p=0.001) respectively (Figs. 2 and 3).

The results of the Cox proportional hazards model, which included an interaction term between status (iSIII/pSIII) and the stage III substages, showed a non-significant value for the interaction (coefficient 0.1898; HR, 1.209; p=0.41), which is indicative that there is no statistically significant evidence that the effect of the iSIII/pSIII group on survival differs systematically across the IIIB, IIIC and IIID substages.

DiscussionMelanoma biology explains differences in prognosis and progression patterns. The disease stage at diagnosis is related to the risk and time of progression, with an earlier relapse in cases of thicker vs thinner tumors.5

As expected, patients with onset of melanoma disease at stage III presented primary tumors with features of worse prognosis, such as higher median Breslow thickness, ulceration, mitotic index and more nodular subtype, than those re-staged as stage III during follow-up. However, once they progressed to stage III, patients of the pSIII cohort had worse outcomes vs the iSIII. In the multivariate analysis, after adjusting for age, sex, Breslow thickness, and ulceration, the pSIII cohort demonstrated a worse prognosis for both MSS and OS. This finding is noteworthy, as most patients in the iSIII cohort were initially diagnosed with stage IIIC disease, whereas the majority of those in the pSIII cohort were initially diagnosed with AJCC stages I or II.

We consider that the differences observed across the different cohorts could be related to multiple factors such as inter- and intra- tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment.15 Among the driver mutations, 4 major genetic subtypes have been described: mutant BRAF, RAS, NF1 and triple wild-type. These mutations affect the regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.15 Other mutations involver are those that affect telomere integrity. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) aberrations are the most common noncoding mutations found in melanoma. Rachakonda et al.,16 found in a study on patients with cutaneous melanoma in early stages, that the HR for poor MSS was 2.05 (95%CI, 1.33–3.16) for short vs telomeres. Furthermore, it found that patients with TERT promoter mutation and concomitant BRAF or NRAS mutations had worse RFS.15 Kuhn et al. observed that TERT expression contributes to early metastasis from thin primaries, potentially through extracellular matrix remodeling.17 Several genes related to metastatic melanoma were identified; among them, DSG1, FLG, PKP1 and BAP-1 were associated with poor OS.15 Other biomarkers have been studied such as tests based on genetic profiling signatures, in order to better identify patients with high risk of relapse and metastasis with high accuracy. 18

Microphtalmia transcription factor (MITF) is a member of the most important transcriptomic family of melanoma and high levels of MITF are present in differentiated melanoma cells. Dedifferentiated melanoma cells present low expression of MITF with high expression of mesenchymal markers. Dedifferentiation is a hallmark of cancer progression and is associated with cross resistance to both targeted and immune therapies in melanoma.19

The interaction between tumor cells and the surrounding microenvironment is essential for acquiring and maintaining tumor cell features, such as sustaining proliferative signaling, resisting cell death, inducing angiogenesis, activating invasion, metastasis, and avoiding immune destruction.20

Tumor microenvironment (TME) includes stromal cells, extracellular matrix and soluble molecules such as chemokines, cytokines, growth factors and extracellular vesicles.20

The most important cell type in TME is the cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF). The transformation of fibroblasts into CAFs is due to the TGF-β released by tumor cells which leads to this transformation. CAFs produce cytokines, chemokines and growth factors related to tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, inflammation and drug resistance; an increased number of CAFs in TME is associated with poor prognosis.21

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and neutrophils (TANs) are also abundant in the TME. TANs release granules containing different proteases such as matrix metalloprotease-9 and neutrophil elastase, promoting extracellular matrix remodelation and tumor invasion. TANs are also related to immunosuppresive factors, as they release arginase 1 and TGF-β.20

Immune inhibitory signaling pathways play a significant role in immunosuppressive microenvironment maintenance. One of the most important inhibitory pathways is the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death -1(PD-1). In response to inflammatory signals, the expression of PD-1 is induced on effector T-cells, while PD-L1 is expressed in lymphocytes, vascular endothelium, mesenchymal stem cells and tumor cells.22

PD-L1 binding to PD-1 lead to CD8+ T cell inhibition and CD4+ T-regulatory lymphocyte activation. PD-L1 is expressed in the tumor microenvironment cells facilitating immune evasion.23

To reduce the risk of relapse and disease progression in patients with stage III and resected stage IV, at present, clinical practice guidelines recommend systemic adjuvant therapy as a complement to surgery. Most clinical trials of adjuvancy included patients in stages IIIA, IIIB and IIIC; however, in those trials whether they were patients in stage III at onset or patients who had progressed from earlier stages was not taken into consideration.7–12

The high cost and variable patient responses to targeted and immune therapies could lead to over- or under- treatment. Reliable biomarkers are needed to identify those patients who are likely to benefit most from therapies.24

The success of immunotherapy in melanoma is likely linked to the high mutational burden (TMB) which generates a large pool of neoantigens triggering robust anti-tumor responses. Other proposed biomarkers include mismatch-repair deficiency, CTLA-4 expression and PD-1-PDL-1 status; however, all these markers have limitations.24

Liquid biopsy biomarkers and machine learning algorithms based on gene expression signatures are being investigated as promising tools to enhance personalized treatment and improve the clinical management of melanoma.25

In our study we found worse MSS and OS in melanoma patients with stage III who had progressed from stages I and II vs melanoma patients at stage III of diagnosis. We consider that progression from initial AJCC stages should be seen as a marker for worse survival in stage III melanoma patients.

This study has limitations. Due to the retrospective nature and the long period of the study which included patients diagnosed and treated before and after the era of molecular studies and adjuvant therapies, the presence of BRAF mutations and whether patients had received adjuvant treatment could not be taken into consideration for analytical purposes. However, we believe that in that case both cohorts could have received treatment in equal proportion. In our study, tumor volume was not assessed by RECIST as in most clinical trials; however, to equate both cohorts to the greatest extent possible and make them comparable, all study patients were staged according to the AJCC 8th edition.

FundingResearch conducted by the Melanoma Group at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona is supported by the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain; AGAUR 2017_SGR_1134 and the CERCA Programme of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain; a research grant from the Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (GCB15152978SOEN), Spain; the European Commission under the Sixth Framework Programme (Contract No. LSHC-CT-2006-018702, GenoMEL); the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Programme (Diagnoptics); the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme (iTobos and Qualitop); and the European Commission under the Horizon Europe Programme (HORIZON-MISS-2021-CANCER-02, MELCAYA; reference 101096667). This research was also partially supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (PI18/00419 and PI22/01467), Spain. Part of this work was carried out at the Esther Koplowitz Center, Barcelona.

Conflict of interestA.L, A.A, D.R, C.C, S.P declare no conflicts of interest.

S.Puig and J. Malvehy declare as COI having grants or contracts with Almirall, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, La Roche Posay, Philogen, ISDIN, International School of Derma, and honoraria for lectures presentations or educational events with Sanofi, Sun pharma, Cantabria, Eucerin, Avene, Pierre Fabre.