Porokeratosis comprises a group of heterogeneous and uncommon acquired or congenital skin diseases of unknown origin characterized by a keratinization disorder resulting from abnormal clonal expansion of keratinocytes. Numerous genetic mutations are thought to be involved. These conditions are characterized histologically by the presence of a cornoid lamella. Clinical manifestations are variable, with localized, disseminated, and even eruptive forms. Porokeratosis has been associated with immunosuppression, ultraviolet radiation, and systemic, infectious, and neoplastic diseases. Many authors consider it to be a premalignant condition because of the potential for malignant transformation to squamous cell or basal cell carcinoma. Therefore, long-term follow-up is a key component of treatment, which is usually complex and often unsatisfactory. We review the latest advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment and propose a treatment algorithm.

Las poroqueratosis son un grupo heterogéneo e infrecuente de dermatosis adquiridas o heredadas de etiología desconocida, caracterizadas por un trastorno de la queratinización secundario a una expansión clonal anormal de los queratinocitos. Se han descrito múltiples mutaciones genéticas potencialmente implicadas. Histológicamente, se caracterizan por la presencia de la lamela cornoide. Su presentación clínica es variable con formas localizadas, diseminadas e incluso eruptivas. Las poroqueratosis se han asociado con inmunosupresión, radiación ultravioleta, enfermedades sistémicas, infecciosas y neoplásicas. Muchos autores las consideran como entidades premalignas dada su potencial degeneración neoplásica a carcinoma escamoso o basocelular. Por ello, el seguimiento a largo plazo es uno de los pilares de su tratamiento, el que suele ser complejo y a menudo insatisfactorio. En la presente revisión se discuten los últimos avances en su etiopatogenia, diagnóstico y terapéutica, y se propone un algoritmo de tratamiento.

Porokeratosis constitutes a rare group of acquired or inherited skin disorders of unknown etiology characterized by aberrant keratinization. Multiple clinical variants have been described, each with varying morphology, distribution, and clinical course. Given its potential for malignant transformation to squamous or basal cell carcinoma, many authors consider porokeratosis to be a premalignant condition.1,2 In this article, we review general aspects of porokeratosis, with a focus on disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), disseminated superficial porokeratosis (DSP), porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM), linear porokeratosis (LP), eruptive disseminated porokeratosis (EDP), porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD), punctate porokeratosis (PP), and other more recently described clinical variants. We also provide a brief overview of the evidence available on different treatment options.

EpidemiologyPorokeratosis is a rare disorder but its exact incidence and prevalence are unknown. It generally affects adults, although certain variants such as PM and DSP can develop in childhood.1,2 No ethnic or racial differences have been described.1 Data from some series suggest that porokeratosis, in particular PM and PPPD, may be more common in men.3,4 LP and DSAP, by contrast, appear to be more common in women.1 DSAP is directly associated with UV radiation and mainly affects whites, hence its relatively high prevalence in countries such as Australia.1

Etiology and PathogenesisAlthough porokeratosis is thought to arise from an abnormal clonal proliferation of keratinocytes, its etiologic and pathogenic mechanisms are unknown.2 Parakeratosis may be due to altered maturation of keratinocytes or acceleration of epidermopoiesis. Premature apoptosis of keratinocytes underlying the cornoid lamella has been observed together with loss of the granular layer and altered loricrin and filaggrin expression.5

Multiple etiologic and pathogenic factors, described below, have been implicated.

- a.

Genetic Factors

A significant number of familial cases of porokeratosis, inherited as an autosomal dominant condition with variable penetrance, have been reported for PM, LP, DSAP, DSP, and PPPD.1,2 Certain sporadic cases are assumed to be due to somatic mutations. It has been postulated that the various forms of porokeratosis might be different phenotypes with a common genetic alteration.2 Multiple genetic loci have been described. The most widely studied variant is DSAP, for which 5 loci have been identified on chromosomes 1, 12, 15, 16, and 18; other loci have been found at 12q23.2–24.1, near the gene responsible for Darier disease, and at 18p11, a susceptibility locus for psoriasis.6–10 A sixth locus on chromosome 12 has also been implicated in PPPD,11but it has been suggested that these cases might actually correspond to PM.12

Genetic mutations in the mevalonate pathway have been linked to DSAP, as they have a role in keratinocyte differentiation and in protecting against UV radiation–induced apoptosis.13 Alteration of this pathway has been observed in 33% of familial cases and 16% of sporadic cases of DSAP.14 Other potentially involved genes, which have a role in epidermal differentiation, are SSH1, SART3, and SLC17A9.15 Localized forms of porokeratosis such as PM and LP may be due to mosaicism (focal loss of heterozygosity through somatic mutations). This would explain the link between localized forms and DSAP in some patients.16

- b.

UV Radiation

The association between UV radiation and porokeratosis is mainly based on findings from experimental and observational studies showing lesions in sun-exposed areas, worsening during summer months, a higher incidence in areas with high sun exposure, and lesions induced by phototherapy.1,17 Nonetheless, there have also been reports of improvement with phototherapy, and DSAP does not tend to affect the face.1

- c.

Immunosuppression

Porokeratosis has also been linked to immunosuppression (particularly in relation to solid organ and bone marrow transplants),1,18 hematologic malignancies, human immunodeficiency virus infection, drugs, and inflammatory and/or autoimmune diseases. Porokeratosis has a reported incidence of 10% in kidney transplant patients, with a time from transplant to onset ranging from 4 months to 14 years (mean, 4–5 years).19 The most common variants of porokeratosis seen in immunosuppressed patients are DSAP and PM, or both simultaneously.18

The mechanism underlying the link between porokeratosis and immunosuppression is uncertain, although some studies have shown increased expression of HLA-DR antigens in epidermal Langerhans cells in porokeratosis lesions,19 possibly indicating altered immunosurveillance resulting in the clonal proliferation of abnormal keratinocytes.

- d.

Other Factors

There have been isolated reports of porokeratosis developing in relation to certain drugs, including suramin, hydrochlorothiazide, furosemide, hydroxyurea, gentamicin, exemestane, flucloxacillin,20,21 and biologics such as etanercept, certolizumab, and trastuzumab.21–23

Porokeratosis has been linked to infections involving human papillomavirus, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis C virus [HCV], and leishmania1,24 and to systemic diseases, such as Crohn disease, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney failure, primary cardiac amyloidosis, acute pancreatitis, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, ankylosing spondylitis, and, mainly in the case of DSP, diabetes mellitus.25–27 It has also been linked to certain genetic disorders, such as trisomy 16, craniosynostosis-anal anomalies-porokeratosis syndrome, Nijmegen breakage syndrome, cystic fibrosis, Werner syndrome, erythropoietic protoporphyria, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome.1,28 Skin disorders associated with porokeratosis include lichen planus, psoriasis, pemphigus, hydradenitis suppurativa, alopecia areata, pyoderma gangrenosum, discoid lupus, vitiligo, and lichen sclerosus.1,29

One serious association is that between porokeratosis and hematologic malignancies or solid organ tumors. This association is particularly strong for EPD (present in up to one-third of patients) and many of the cases have criteria suggestive of a paraneoplastic manifestation.30,31 The association could be due to paraneoplastic immunosuppression or to the coexistence of viral infections such as HCV infection, which can cause mutations that disrupt the function of the tumor suppressor p53 gene.30

There have also been reports linking porokeratosis to traumatic factors, as lesions have been observed at hemodialysis sites and in burn wounds.32,33 Electrotherapy and ionizing radiation have also been suggested as possible triggers.34

Porokeratosis and Malignant TransformationKeratinocytes underlying the cornoid lamella exhibit varying degrees of dysplasia.2,35 The initial mechanism for malignant transformation would be allelic loss associated with p53 overexpression.36,37 Other proteins, such as psi-3, cytokeratin, filaggrin, and involucrin, may also be involved. UV radiation may act as a trigger by inducing p53 mutations.2

Porokeratosis is considered a premalignant condition, as all its variants have a potential for malignant transformation. The most common cancer is squamous cell carcinoma followed by basal cell carcinoma.35 Malignant lesions are solitary in approximately 2 to 3 cases and are frequently located on non–sun-exposed skin on the extremities; they can appear up to 36 years after onset of porokeratosis.2 The estimated incidence of malignant transformation is 7.5% to 11.%38,39 (Table 1). The risk is greater with larger lesions, as they have a hypertrophic epidermis and more DNA ploidy alterations.40

Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of the Various Subtypes of Porokeratosis.

| Frequency | Epidemiology | Triggers | Clinical Manifestations | Associations | Association With Skin Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSAP | 42% (most common subtype) | Third-fourth decade F>M (1.8:1) | UV radiation | Erythematous skin-colored or hyperpigmented annular papules with a keratotic border, symmetrically distributed on the arms, legs, shoulders, and back | Rare (3%) | |

| Generally asymptomatic | ||||||

| DSP | Rare | Childhood (5–10 years) | Immunosuppression | Same clinical features as DSAP, but affects both sun-exposed and non–sun-exposed areas | Solid organ tumorsa | Rare |

| Porokeratosis of Mibelli | 35% (second most common subtype) | Childhood | Immunosuppression in adults | Small, asymptomatic or mildly pruritic papules; slow progression to solitary or isolated plaques of several centimeters in diameter, usually on the trunk and/or limbs | 8% | |

| M>F (2–3:1) | ||||||

| Linear porokeratosis | 13% | Childhood, occasionally adulthood | Similar to DSAP but with a linear distribution following Blaschko lines; may be segmental or generalized | 19% | ||

| F>M (1.6:1) | ||||||

| EDP | Very rare (about 30 cases described) | Middle age | Hepatotropic viruses, malignancy | Abrupt onset of erythematous papules with keratotic borders and a progressive course; intensely pruritic | Hepatic-digestive and hematological malignancy (one-third of cases) | Rare |

| M>F | ||||||

| Porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata | Very rare | Adolescence or early adulthood | UV radiation | Bilateral, symmetric keratotic papules measuring 1–2mm on the palms and/or soles; may be generalized with DSAP-like lesions on the trunk and limbs or affect mucous membranes | 10% | |

| (<20 reported cases) | ||||||

| Punctate porokeratosis | Very rare | Adolescence or early adulthood | Keratotic seed-like depressed or spiculated papules measuring 1-2 mm on the palms and soles | Rare | ||

| Porokeratosis ptychotropica | Very rare | Middle age | Trauma, scratching | Progressive verrucous hyperkeratotic plaques on the buttocks (in a butterfly pattern) and in the perianal region; | Rare | |

| 90% men | Intensely pruritic | |||||

| Penoscrotal porokeratosis | Very rare | Third decade | Trauma, scratching | Granular patches and plaques on the shaft of the penis and anterior scrotum; pruritic | Rare | |

| Follicular porokeratosis | Very rare | All ages | Macules, papules, or annular plaques with erythematous borders mainly affecting the face | Rare | ||

| (11 cases reported) | M>F |

Abbreviations: DSAP, disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis; DSP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis; EDP, eruptive disseminated porokeratosis; F, female; M, male.

Porokeratosis presents as well-delimited papules or erythematous-brownish plaques of varying shapes and sizes with centrifugal growth. The border is formed by a thin keratotic ridge pointing towards the center of the lesion, which can be depressed or slightly atrophic, or, less frequently, hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1,2

An overview of the different clinical variants of porokeratosis, which differ in lesion number, size, shape, and distribution, is given below and summarized in Table 1.

- a.

Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

DSAP is the most common form of porokeratosis, accounting for 56% of all clinical variants.4 It is directly related to sun exposure and typically presents in the third or fourth decade of life and is more common in women (female to male [F–M] ratio, 1:8:1). It is characterized by multiple small annular papules (sometimes in their hundreds) that sometimes coalesce into polycyclic plaques. They are distributed symmetrically on the back and the extensor surface of the extremities1,2 (Fig. 1A–B). The face is affected in just 15% of cases.41 DSAP is usually asymptomatic, but it can cause pruritus in up to one-third of patients.1 More than 50% of patients report worsening during the summer or after phototherapy.42

- b.

Disseminated Superficial Porokeratosis

DSP is similar to DSAP, but is not triggered by UV radiation and is characterized by early onset (age 5–10 years).1,2 It has been described in association with congenital LP in an infant and a child of preschool age.43,44

Lesions are observed on both sun-and non-sun-exposed skin, mainly on the trunk and genitals and in acral regions (Fig. 1C–), although the mouth can also be affected.2,45

- c.

Porokeratosis of Mibelli

PM is the second most common form of porokeratosis.3 It usually develops in childhood or adolescence, although adult onset has been described; it is more common in male patients (M–F ratio, 2–3:1).46 It presents as one or more annular plaques with an atrophic, or less frequently, hyperkeratotic center. It is unilateral and shows progressive growth. Giant PM lesions can exceed 20 cm and have high malignant potential1,47 (Fig. 3A). PM usually occurs on the trunk or extremities, although acral, facial, genital, scalp, and oral mucosal lesions have been described.1,2 Isolated cases of a possible hyperkeratotic variant consisting of multiple, verrucous lesions on the extremities have been described.48

- d.

Linear Porokeratosis

LP is an uncommon variant of porokeratosis that predominantly affects females (F–M ratio, 1.63:1).2 For some authors, rather than a separate entity, LP is a linear form of PM or DSAP.49 It is characterized by multiple papules or hyperkeratotic plaques in a linear distribution on the extremities (Fig. 2A–B). Lesions usually follow a Blaschkoid pattern, although exceptionally they may be segmental or generalized, reflecting genetic mosaicism.50 LP is usually congenital, although adult onset has been described. It may coexist with DSAP, probably as a result of postzygotic mutations causing loss of heterozygosity (type 2 mosaicism).49,51

- e.

Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis

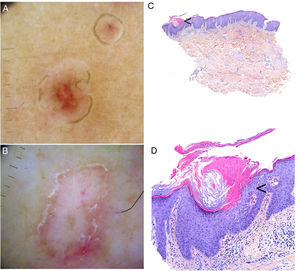

A–B, Linear porokeratosis. Erythematous-brownish plaques with a scaling border and a linear distribution in the right costal region (A) and on the left thigh (B). C–D, Disseminated superficial porokeratosis. Multiple plaques with an annular erythematous hyperkeratotic border on both arms (C) and the left leg (D); the lesions were intensely pruritic.

EDP encompasses eruptive pruritic papular porokeratosis and inflammatory DSP. It is uncommon and is characterized by the abrupt appearance of erythematous and intensely pruritic skin lesions (Fig. 2C–D). Although EPD has not been clearly defined, some authors have subdivided it into paraneoplastic, immunosuppression-related, inflammatory, and other forms. Paraneoplastic variants may resolve on completion of the cancer treatment, while inflammatory variants can resolve spontaneously.52,53 In our review of the literature, we found 30 cases of EPD, most in middle-aged men (range, 13–84 years). Over 50% of patients had had a previous form of porokeratosis (most often DSP). The most characteristic histologic finding was the presence of a cornoid lamella and a dermal inflammatory infiltrate (with a predominant lymphohistiocytic component in 9 cases and a predominant eosinophilic component in 8). Some authors have described an inflammatory infiltrate with CD8+ lymphocytes (CD4+ cells are more common in DSP) and suggested that EPD might represent an immune response mediated by CD8+ lymphocytes against abnormal keratinocyte clones.54,55 The most important clinical aspect of EPD is that almost one-third of patients have a malignancy (mainly of hepatobiliary or hematologic origin).18,21,31,56–60 It is important thus to screen for these diseases in all patients with EPD (Table 2). Viral infection (herpes simplex virus, HCV,57 or hepatitis B virus) has been reported in almost 20% of patients with EDP, which can also affect immunosuppressed patients61 and patients on certain medications.21 In the vast majority of cases (75%), EPD resolves spontaneously within about 6 months (although it can take up to 2 years). Response to topical or systemic treatment is highly variable, and is inexistent or low in most cases.

- f.

Porokeratosis Palmaris et Plantaris Disseminata

Cases Described in the Literature of Eruptive Disseminated Porokeratosis Associated With Malignancy.

| Sex/Age, y | Associated Malignancy | Previous Porokeratosis | Histology | Treatment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levin et al., 199960 | M/70 | Myelodysplastic syndrome | ND | Cornoid lamella | None | ND |

| Kono et al., 200057 | M/67 | HCC associated with HCV infection (2 mo after EPPP) | No | Cornoid lamella | Percutaneous ethanol injection (HCC) | Good response for HCC and cutaneous lesions |

| M/62 | HCC associated with HCV infection (6 mo after EPPP) | No | Diagnosis of DSPa | Percutaneous ethanol injection (HCC) | Good response for HCC and cutaneous lesions | |

| F/58 | HCC associated with HCV infection (after EPPP) | No | Diagnosis of DSPa | None | ND | |

| Lee et al., 200658 | F/73 | Cholangiocarcinoma | No | Cornoid lamella, dyskeratosis | None | The skin lesions increased for the following 6 mo |

| Cannavó et al., 200831 | F/54 | Ovarian adenocarcinoma | No | Cornoid lamella | None | Remission of lesions after 6 cycles of chemotherapy (ovarian adenocarcinoma responded well) |

| Choi et al., 200959 | M/84 | Colorectal carcinoma (6 y after onset) | Yes, DSP | Cornoid lamella, dermal infiltrate with eosinophils and lymphocytes | Topical CSs and antihistamines | Good response after 1 mo |

| Spontaneous regression after 4 mo | ||||||

| Schena et al., 201056 | F/77 | Pancreatic cancer | No | Cornoid lamella, dyskeratosis, lymphohistiocytic infiltrate | ND | Died after 2 wk |

| Pini et al., 201218 | M/13 | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (allogenic transplant 1 y before EPPP) | ND | Cornoid lamella, dyskeratosis Dermal lymphocytic infiltrate | Topical urea | No response |

| Spontaneous resolution on interruption of immunosuppression | ||||||

| Mangas et al., 201821 | F/62 | Metastatic breast cancer (treatment with trastuzumab and exemestane) | ND | Cornoid lamella, hypogranulosis | Topical betamethasone and salicylic acid | Improvement of symptoms |

| Persistence of skin lesions |

Abbreviations: CSs, corticosteroids; DSAP, disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis; DSP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis; EPPP, eruptive pruritic papular porokeratosis; F, female; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; M, male; ND, not described.

PPPD is another uncommon variant of porokeratosis, with fewer than 20 cases described in the literature. Most cases are familial and are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. PPPD usually starts in adolescence and mainly affects males (M-F ratio, 2:1).62 It is clinically similar to DSP, with bilateral, symmetric keratotic papules measuring 1 to 2mm. In most cases it starts on the palms and soles and then spreads to the rest of the body after several months or years.62,63 There have, however, been anecdotal cases of lesions starting on the trunk and extremities and then spreading to the palms and soles.64 It may worsen during the summer.

- g.

Punctate Porokeratosis

PP has been described by some authors as a subtype of PPPD.65 It starts in adolescence or young adulthood and is characterized by multiple seed-like keratotic papules on the palms and soles. These papules measure 1 to 2mm and may be depressed (pits) or raised (spiculated). PP frequently occurs in association with PM or LP.65,66

- h.

Genitogluteal Porokeratosis

All variants of generalized porokeratosis can affect the genitals and gluteal region, but there have been few reports of exclusive genitogluteal involvement.67 Three clinical variants have been described:

- 1.

Classic porokeratosis in the genital region. Genital porokeratosis affects middle-aged adults and has a predilection for men. It has been suggested that it may be more common in Asians and Afroamericans.68,69 Friction and scratching may be determining factors. It manifests as intensely pruritic annular plaques with an atrophic center on the scrotum, penis, buttocks, or proximal thigh.68

- 2.

Porokeratosis ptychotropica. The word ptychotropica comes from the Greek words ptyhce, meaning fold, and trope, meaning turn.70 It is a very rare variant of porokeratosis, with fewer than 30 cases described in the literature. It affects middle-aged adults (90% men).71 It is characterized by thick, pruritic, erythematous-brownish, verrucous plaques that exhibit slow, progressive growth and affect the perianal region, the buttocks, and the intergluteal cleft, forming a butterfly-wing pattern and satellite lesions (Fig. 3B). It can also affect the genitals.68 Diagnostic delay is common as the condition is confused with eczema, genital warts, or mycosis.71 It can be differentiated histologically by the presence of multiple cornoid lamellae throughout the lesion and not just at the border. Amyloid deposits may also be observed in the papillary dermis.72 Infectious agents have not been demonstrated in lesions and there appears to be no link to human papillomavirus infection.73

Figure 3.A, Porokeratosis of Mibelli. Round, erythematous plaque measuring 4cm with a raised hyperkeratotic border on the left knee. Diagnosis was confirmed by histology. B, Porokeratosis ptychotropica. Multiple coalescent erythematous scaling plaques with a hyperkeratotic edge in the perianal area and on the right buttock.

- 3.

Penoscrotal porokeratosis. This variant has been described in patients in their third decade of life and is characterized by granular plaques on the shaft of the penis and the anterior scrotum. It is intensely pruritic.68,74 As with porokeratosis ptychotropica, multiple cornoid lamellae are observed during histologic examination.74

- i.

Follicular Porokeratosis

Follicular porokeratosis was described for the first time a decade ago,75 and just 11 cases have been reported. It can occur at all ages and appears to be slightly more common in men.76 It manifests as macules-papules or annular plaques with keratotic borders. It mainly affects the face, but may be observed on the trunk and extremities.77 The characteristic histologic finding is a cornoid lamella arising from dilated follicles.75,76

- j.

Other Variants

There have been isolated reports of pustular,78 ulcerative,79 bullous,80 and reticulated81 porokeratosis, prurigo nodularis-like lesions82 and seborrheic keratosis-like porokeratosis.83

One recent report described porokeratoma, a porokeratotic acanthoma with multiple cornoid lamellae. This variant manifests as one or more verrucous lesions on the extremities, trunk, or buttocks.84 Some authors see it as a variant of hyperkeratotic porokeratosis, while others believe it to be a separate entity.85

Diagnosis- a.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of porokeratosis is often exclusively clinical, with skin biopsy reserved for atypical or doubtful cases.

- b.

Dermoscopy and Other Imaging Techniques

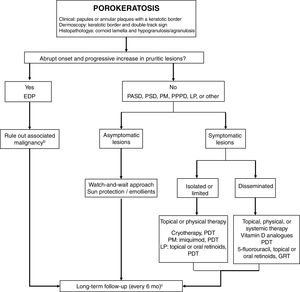

Dermoscopic findings in the varying clinical forms of porokeratosis include a hyperkeratotic white, yellow, or brown peripheral edge (double-track sign), a homogeneous central area that may have a scar-like appearance or contain brown dots or globules or vascular structures, such as irregular globular and linear vessels crossing the lesion86,87 (Fig. 4A–B). Ink-enhanced dermoscopy can be useful, as when the lesion is cleaned with alcohol 70%, the ink remains at the ridge-like cornoid lamella, differentiating it from other skin conditions.88

Porokeratosis. A–B, Dermoscopy. Erythematous brownish lesion without clearly defined structures and with a brownish annular border (A). Lesion with structureless white areas and dotted vessels and a hyperkeratotic annular border. Note the double-track sign (B) (Gen Dermlite DL200, ×8). C–D. Histology. Epidermal invagination with a parakeratotic column (cornoid lamella) (arrow)) (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×40) (C). Cornoid lamella (D). Note the loss of the granular layer underlying the parakeratotic column (arrow) and the keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×200). Cornoid lamella (arrow) (hematoxylin–eosin, ×100).

The cornoid lamella is discerned as a bright parakeratotic structure without an underlying granular layer by reflectance confocal microscopy.87 This structure can also be visualized by optical coherence tomography.2

- c.

Histology

Biopsy of the border of a porokeratotic lesion shows a well-delimited column of parakeratotic cells (cornoid lamella). There may also be hypogranulosis or agranulosis in this area and occasional dyskeratotic cells or vacuolated keratinocytes (Fig. 4C–D). There have been isolated reports of eosinophilic spongiosis. Additional findings include a small perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes.1,2 A CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate has been observed in EDP.55 Finally, mild orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis can be seen in the center of lesions.1

Differential DiagnosisMultiple entities should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the clinical variants of porokeratosis (Table 3).1,2,46,66,89 The most characteristic histologic feature of porokeratosis is the cornoid lamella.

Differential Diagnosis for Porokeratosis.

| Subtype of Porokeratosis | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| DSP and DSAP | Actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, lichen planus, tinea corporis, psoriasis, nummular eczema, and pink pityriasis |

| PM | Bowen disease, granuloma, palmoplantar/circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis, lichen simplex chronicus, tinea corporis, sarcoidosis |

| LP | Linear warts, lichen striatus, linear verrucous epidermal nevus, linear Darier disease, and porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus |

| PPPD and PP | Hereditary punctate palmoplantar keratoderma, spiny keratoderma, Gorlin syndrome, Darier disease, arsenical keratosis, and palmoplantar lichen nitidus |

| Porokeratosis ptychotropica | Psoriasis, enteropathic acrodermatitis, and necrolytic migratory erythema |

Abbreviations: DASP, disseminated actinic superficial porokeratosis; DSP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis; LP, linear porokeratosis; PM, porokeratosis of Mibelli; PP, porokeratosis punctata; PPPD, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata.

Source: Kanitakis et al.,1 Sertznig et al.,2 Ferreira et al.,46 Teixeira et al.,66 Elfatoiki et al.89

The cornoid lamella, however, can also be observed in verruca vulgaris, actinic keratosis, certain ichthyoses, and nevoid hyperkeratosis, but in porokeratosis, the granular layer underlying the parakeratotic column is usually absent.2 A cornoid lamella may also be observed in keratosis punctata, an inheritable condition, and spiny keratoderma, making distinction from PPPD and PP difficult. Nonetheless, dyskeratotic cells or vacuolated cells are usually observed in PPPD and PP.66 In addition, multiple cornoid lamellae are observed in porokeratoma and genitogluteal porokeratosis.71,84

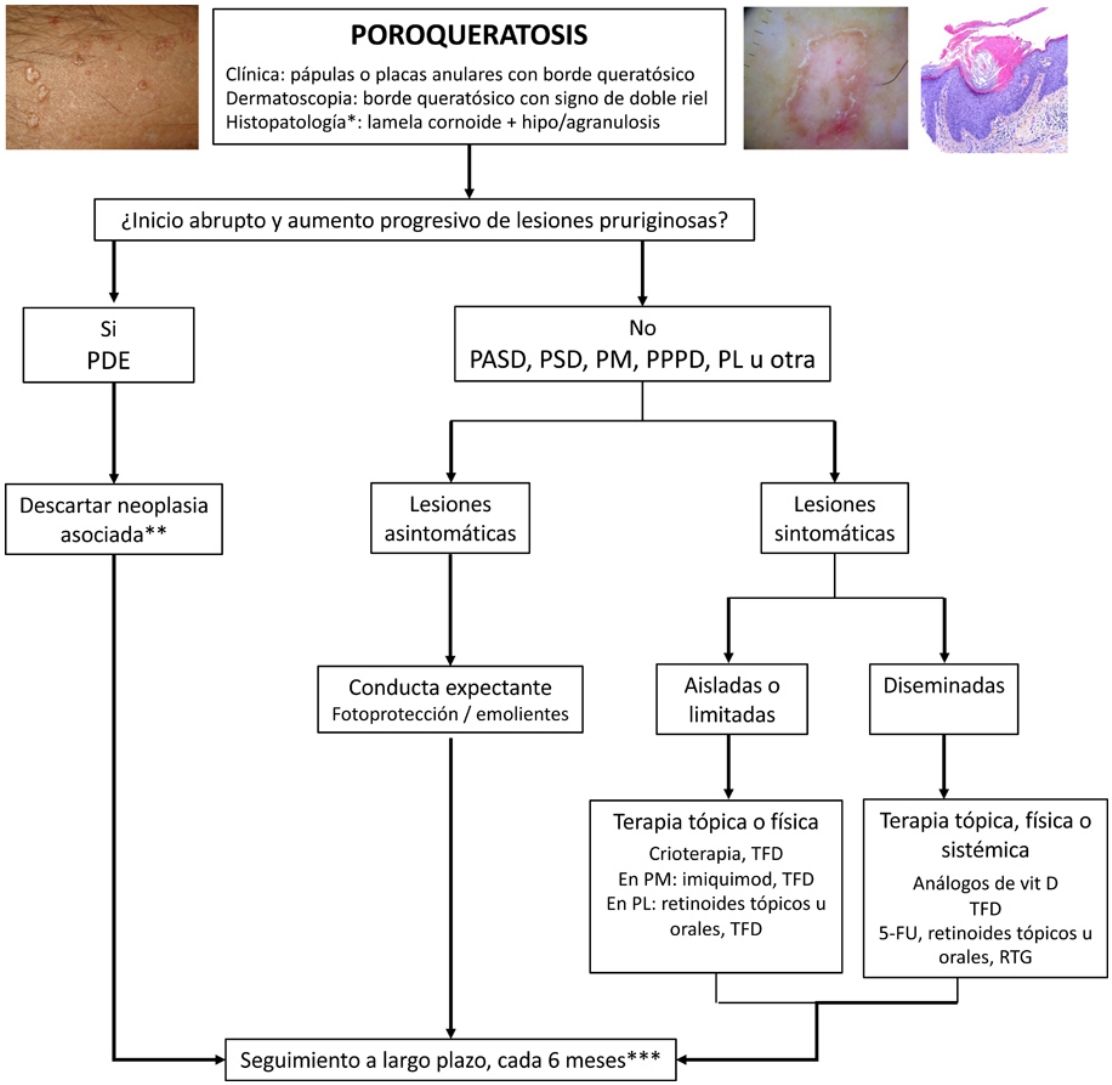

TreatmentPorokeratosis tends to follow a chronic course and is often refractory to treatment, with just 16% of patients achieving complete response.4 A watch-and-wait approach—with adequate use of sun protection and emollients and regular long-term follow-up—is a valid option for asymptomatic patients or patients (Fig. 5). Follow-up is particularly important considering the risk of malignant transformation, particularly in the case of PM, LP, PPPD, and large lesions.1 An exhaustive search for underlying malignancy, particularly of hepatobiliopancreatic or hematologic origin, is warranted in patients with EDP.52

Treatment algorithm for porokeratosis. 5-FU indicates 5-fluorouracil; DSAP, disseminated actinic superficial porokeratosis; DSP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis; EDP, eruptive disseminated porokeratosis; GRT, Grenz ray therapy; LP, linear porokeratosis; PDT, photodynamic therapy: PM, porokeratosis of Mibelli; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PPPD, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata.

a Histology only in atypical or doubtful cases.

b Mainly of hepatobiliopancreatic and hematologic origin. Order complete blood count, liver profile, lactate dehydrogenase, and computed tomography of the chest and abdomen.

c Rule out skin cancer (squamous and basal cell carcinoma).

No controlled clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of the different treatment options available for symptomatic porokeratosis, and existing recommendations are based mainly on case reports, small series with fewer than 20 patients, and 2 systematic reviews.90,91Table 4 summarizes the different topical, systemic, and physical treatment options available, together with information on level of evidence. Cryotherapy,92, curettage, electrosurgery, photodynamic therapy, and surgical excision are possibilities for smaller, symptomatic lesions, but there is a risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or scarring.90,93 Topical vitamin D analogues and retinoids, 5-fluorouracil, and imiquimod 5% may be indicated for larger or multiple (but localized) lesions.90,94 Imiquimod appears to be the best option for PM.90 Topical or oral retinoids could be used as first-line treatment for LP,90 while photodynamic therapy could be recommended as first- or second-line treatment for localized forms of porokeratosis.

Treatment of Porokeratosis and Clinical Response.

| Administration Route | Drug | Study Type | Type of Porokeratosis | Response to Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical | Salicylic acid | 3 case reports | 2 cases of genitogluteal porokeratosis and 1 of plantar PP | Complete response in genitogluteal porokeratosis with topical corticosteroids and in PP with topical 5-fluorouracil |

| Corticosteroids | 4 case reports | 1 case each of EDP and PM and 2 cases of genitogluteal porokeratosis | Partial response in EDP (antihistamines also used), no response in PM, and control of symptoms in genitogluteal porokeratosis (salicylic acid also used) | |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 6 case reports | 3 cases of PM and 1 case each of DSAP, PP, and seborrheic keratosis-like porokeratosis | Complete response in 1 case of PM (imiquimod also used) and partial response in other 5 cases | |

| Imiquimod 5% | 11 case reports | 9 cases of PM, 1 of DSAP, and 1 of LP | Complete resolution in all cases | |

| Vitamin D3 analogues (calcipotriol, tacalcitol) | 8 case reports | 8 cases of DSAP, 1 of LP, and 1 of seborrheic keratosis-like porokeratosis | 3 complete responses, 6 partial responses, and 1 no response | |

| 1 case series (n=2) | ||||

| Diclofenac 3% | Prospective multicenter study (n=17) | 25 cases of DSAP and 1 of genitogluteal porokeratosis | Partial improvement in 46% of cases | |

| 1 case series (n=8) | ||||

| 1 case report | ||||

| Retinoids | 5 case reports | 2 cases each of LP and PM, 1 case of DSAP and LP, and 1 case each of DSAP, FP, and “zosteriform porokeratosis” | 4 complete responses, 2 mild improvements | |

| 1 case series (n=3) | ||||

| Ingenol mebutate 0.05% | 1 case report | PM | Partial response | |

| Cantharidin | 1 case series (n=2) | 2 cases of PM | Complete response | |

| Tacrolimus 0.1% | 1 case report | LP | Complete response (betamethasone ointment also used) | |

| Systemic | Retinoids (acitretin, etretinate, isotretinoin) | 10 case reports | 3 cases each of LP and facial porokeratosis, 2 cases of DPPP, and 1 case each of hyperkeratotic porokeratosis and genitogluteal porokeratosis | 6 complete responses and 7 partial responses |

| 1 case series (n=3) | 1 case each of PSD, 1 porokeratosis ptychotropica, and PM | |||

| Palifermin | 1 case report | DSAP | Complete response | |

| Corticosteroids (prednisolone, dexamethasone) | 2 case reports | 1 cases of DSP and 1 of PM | 1 complete response and 1 partial response | |

| Ciclosporin | 1 case report | EDP | Near-complete response | |

| Physical | Cryotherapy | 3 case reports | 10 cases of PM and 1 each of DSAP, LP, and genitogluteal porokeratosis | Complete response in all cases |

| 2 case series (2 and 8 patients, respectively) | ||||

| Shaving, electrodessication, curettage | 2 case reports | 1 case of PM and 1 of porokeratosis ptychotropica | Complete response in both cases | |

| Dermabrasion | 2 case reports | 1 case of PM and 1 of LP | Complete response in both cases | |

| Surgical aspiration with ultrasound | 1 case report | Vulvar porokeratosis | Partial response | |

| Conventional PDT (methyl aminolevulinate, aminolevulinic acid, hypericin) and daylight PDT | 7 case reports | 31 cases of DSAP,a 5 of PM, 4 of LP, and 2 of porokeratosis ptychotropica93 | Complete response in 31% of patients and partial response in 35% | |

| Prospective multicenter study (n=16) | ||||

| 7 case series (1 with 6 patients, 1 with 3, and 5 with 2a) | ||||

| Laser therapy: carbon dioxide, Q-switched erbium: YAG, Nd:YAG, fractional photothermolysis, PDL | 10 case reports | 7 cases of DSAP, 3 of PM, and 1 each of porokeratosis ptychotropica, facial porokeratosis, and reticulated porokeratosis | 7 complete responses, 4 partial responses, and 2 no responses | |

| 1 case series (n=3) | ||||

| Intense pulsed light | 1 case series (n=10) | LP | Just 1 case of partial improvement | |

| Grenz ray therapy | 1 case report | Bullous DSAP | Complete response in all cases | |

| 1 retrospective study (n=8)101 | DSAP |

Abbreviations: DSAP, disseminated actinic superficial porokeratosis; DSP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis; EDP, eruptive disseminated porokeratosis; FP, follicular porokeratosis; LP, linear porokeratosis; PDL, pulsed dye laser; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PM, porokeratosis of Mibelli; PP, porokeratosis punctata; PPPD, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata

In the case of disseminated disease, such as DSAP or DSP, there have been multiple case reports describing good response to vitamin D analogues, with very few or no adverse effects.95 Some authors therefore recommend this option as a first-line treatment for disseminated lesions.90 In a prospective study of 17 adults with DSAP, the largest conducted to date in patients with porokeratosis, topical diclofenac 3% applied for a period of 3 to 6 months prevented lesion progression in over 50% of cases.96 However, in another series of 8 patients also treated with topical diclofenac 3%, just 2 patients responded (partial response).97 Conventional or daylight photodynamic therapy is among the most studied treatments (approximately 42 patients). Response rates ranged from 31% for partial response to 35% for complete response (with the best results observed for DSAP).90,91,98,99 This treatment can, however, cause considerable adverse effects.91 Various forms of laser therapy have been used in a small number of patients (around 13) and have shown promising results, with good response rates and few adverse effects.91 While effective in numerous skin disorders, intense pulsed light was not found to be beneficial in a series of 10 patients with DSP (1 complete response).100 Another form of physical therapy is Grenz ray therapy (GRT). In one retrospective study, all 8 patients achieved complete response with 6 to 10 sessions of GRT at a total dose of 28 to 52 Gy. The treatment had to be interrupted in just 1 patient (due to adverse effects) and another experienced recurrence. None of the patients developed skin carcinoma on the irradiated surface during clinical follow-up.101 Oral retinoids have been used in 13 patients (6 complete and 7 partial responses),102 while systemic corticosteroids have been used in 2 patients (1 complete response)2,90 and ciclosporin in 1 (a near-complete response).103

ConclusionsPorokeratosis is a rare skin disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical variants with which clinicians should be familiar in order to avoid errors and diagnostic delay. Long-term follow-up is important to check for early signs of skin malignancy, a risk that exists in all variants of porokeratosis. Solid organ or hematologic malignancies should be ruled out in patients with eruptive disease. The treatment of porokeratosis is complex and often unsatisfactory, and a watch-and-wait approach may be an option to take into account.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fustà-Novell X. Poroqueratosis. Revisión de su etiopatogenia, manifestaciones clínicas, diagnóstico y tratamiento. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545–560.