Medical photography is a noninvasive technique used for diagnostic, monitoring, and educational purposes. It is important to understand the patient's attitude to all or part of their body being photographed. The objective of this study was to analyze the attitudes of patients towards medical photography at a district hospital in Tarragona, Spain.

MethodologyThis exploratory study used a questionnaire to evaluate attitudes to medical photography among outpatients at Pius Hospital de Valls. The questionnaire explored the patients’ beliefs about the usefulness of medical photography, the circumstances in which they would agree to be photographed and by whom, as well as their prior experience of medical photography. They were also asked whether they would authorize the use of photography and, if not, to explain their motives.

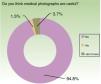

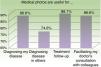

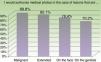

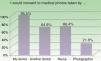

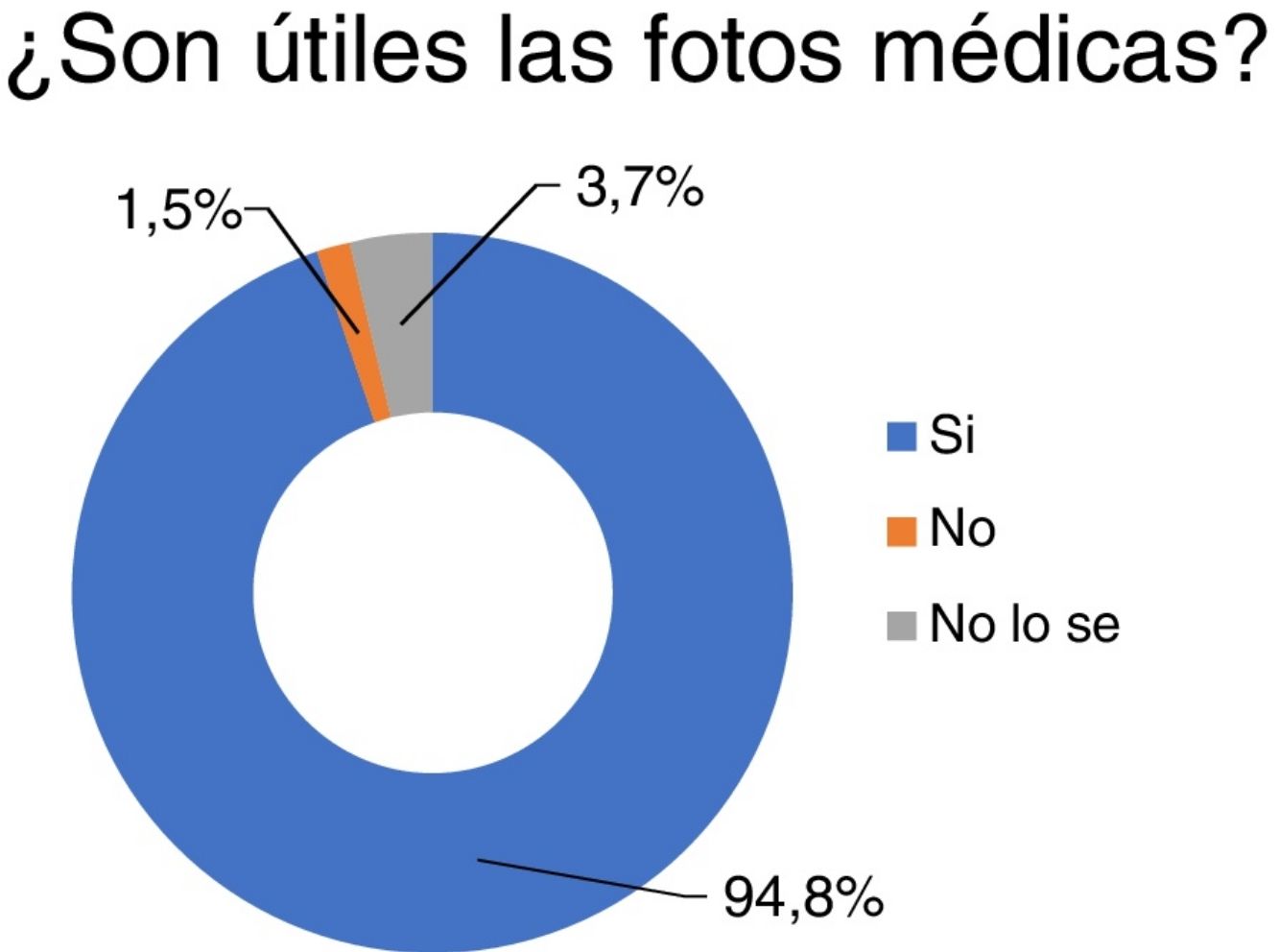

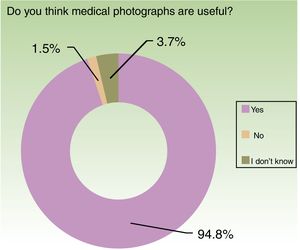

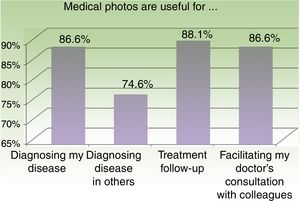

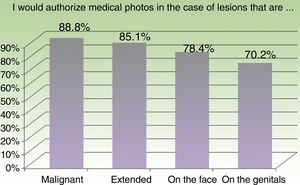

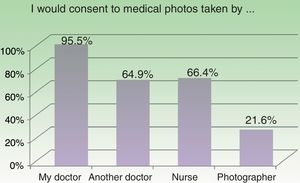

ResultsThe questionnaire was completed by 134 patients. The results showed that patients had a clearly positive attitude to being photographed for medical purposes (94.8%), treatment follow-up (88.1%), and consultation of their case with other physicians (86.6%). Acceptance was 88.8% if the lesion was malignant and 85.1% if it was extensive. For facial lesions, only 78.4% were willing to be photographed and in the case of genitals the percentage fell to 70.2%. Most patients (95.5%) would agree to being photographed by their doctor. The rate of acceptance was 66.4% in the case of a nurse, 64.9% for another doctor, and 21.6% for a professional photographer.

ConclusionsOur study revealed that patients have a positive attitude to being photographed for medical purposes, particularly when they have a malignant lesion, when the photograph is taken by their specialist, and when they cannot be identified.

La fotografía médica es una técnica de imagen no invasiva que se utiliza con fines diagnósticos, de monitoreo y educativos. Es importante conocer la actitud del paciente hacia ser fotografiado, en su totalidad o en parte de su cuerpo. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la actitud de los pacientes del Pius Hospital de Valls hacia la fotografía médica.

MetodologíaEste estudio exploratorio evaluó, a partir de un cuestionario, la actitud de los pacientes que asistieron a consultas externas del Hospital Pius de Valls (España) respecto a ser fotografiados. Las preguntas estaban relacionadas con creencias en torno a la utilidad de la fotografía médica, circunstancias bajo las cuales se autorizaría ser fotografiado y a manos de quién, experiencia con la fotografía médica, intención de autorizar la fotografía y motivos para no autorizarla.

ResultadosEl cuestionario fue respondido por 134 pacientes. Los resultados mostraron una actitud claramente positiva hacia ser fotografiado con fines médicos (94,8%), por seguimiento de tratamiento (88,1%) y consulta del caso con otros médicos (86,6%). El 88,8% aceptaría ser fotografiado si la lesión es maligna y el 85,1% si es extensa. Para lesiones en el rostro, solamente el 78,4% lo permitiría; en los genitales el porcentaje es aún menor (70,2%). El 95,5% estaría dispuesto a dejarse fotografiar si es el mismo médico quien la hace, si es el enfermero (66,4%), otro médico (64,9%) o un fotógrafo profesional (21,6%).

ConclusionesNuestro estudio muestra una actitud positiva hacia ser fotografiado con fines médicos, siempre que el fotógrafo sea el médico tratante, en lesiones malignas y en áreas no identificables.

Medical photography is a noninvasive imaging technique that allows us to record, compare, follow up, and monitor changes as well as to show patients lesions they are unable to see; the images obtained can also be used to diagnose the condition, request second opinions, and for educational purposes.1 Teledermatologists diagnose patients on the basis of clinical photographs and dermoscopic images without a face-to-face consultation.2 When discussing medical photography, we must approach the question from 2 perspectives: that of the person taking the photograph and that of the subject.

The photographer may be the attending physician, a nurse or other auxiliary staff member, or a professional medical photographer. Many different considerations must be taken into account in this setting: ethical concerns (respect for the patient's feeling and intimacy, a commitment to use the images exclusively for the stated purpose);3 legal issues (compliance with legislation on informed consent as well as on the secure storage and transfer of the images); and technical issues related to how, where, and when the clinical photographs are taken.1 The first step with respect to the subject—or patient—is to obtain their informed consent. The patient's response when asked to authorize photography will be influenced by how they feel about being photographed and whether what is required is an image of the whole body or a certain area. Their attitude will be shaped by many factors, including culture,4 religion,5 age, and mentality, among others. Understanding how the patient feels before the session allows the person taking the photographs to approach the task in a more respectful and ethical way.

Any study of attitudes towards medical photography will involve an evaluation of the beliefs, feelings, and intentions6 of the subject in relation to such photography and, ultimately, how they feel about allowing someone to photograph an area of their skin for medical purposes. Our attitudes are shaped by experiences, our own and those of others, and also by the messages communicated by significant individuals and groups about certain things or attitudinal areas.6 In the case of medical photography, the information received by the general public and by patients obviously plays an important role, in particular information on the methods used and the benefits obtained.

In general, the photograph reveals the person; it presents the subject and exposes them to their own and the other's gaze.7 Today, photography is ubiquitous, primarily in the hands of nonprofessionals using mobile phones. As people are constantly taking photographs and being photographed, the symbolism of the act has been almost emptied of its significance. The democratization and trivialization of photography appear to go hand in hand.8 Medical photography, in particular, conjures up instrumental meanings related to the skin in a medicalized body: the skin becomes an area delimited by a scientific and technical viewpoint (dermatology) and a device (the camera lens) employed for precise and specific ends (medical diagnosis and treatment) linked to an ethic rooted in the respectability of the person taking the photograph and in the positive preventative and curative consequences of the action.

The present study was carried out to explore attitudes to medical photography among patients attending the dermatology department in Pius Hospital de Valls in Tarragona, Spain.

Materials and MethodsWe undertook an exploratory study of a nonrandomized group selected by accidental sampling, that is, a sample recruited over time and determined by real life circumstances, taking into account the sociodemographic variables considered important in light of current theories about and research on the formation of the attitudes under study.9

The data was collected by way of a self-administered questionnaire almost exclusively consisting of closed questions (see Annex 1 online). The respondents were anonymous and the questionnaire was made available in 2 languages: Spanish and Catalan. The questionnaire had been piloted in a preliminary study in February 2018 at the same hospital. The patients who completed the questionnaire had appointments for either first or second visits at the dermatology, gynecology, traumatology, or gastroenterology departments between March and May 2018. Some of the dermatology patients were already familiar with the use of medical photography because either they or a family member had been treated by our teledermatology service. This prior experience was recorded in answer to one of the questions on the questionnaire. In the teledermatology consultations, the photographs had been taken by the patient's family physician with verbal consent. When it was deemed necessary, given the patient's condition, to maintain a photographic record in the department, prior written informed consent had been obtained.

The questions were selected with a view to exploring the following topics: the patient's beliefs about the usefulness of medical photography, the circumstances in which they would agree to be photographed and by whom, as well as their own and their family members’ prior experience of medical photography. They were also asked whether they intended to authorize the use of photography and, if not, to explain their motives.

Data was collected on the sociodemographic variables we considered might influence or affect the individual's attitudes to photography: age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupation, place of residence, country of origin, and religion (practicing or non-practicing).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Pius Hospital de Valls.

Organization and Data ProcessingThe data were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet and then imported into the SPSS program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0, Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analysis. Given the homogeneity of the raw data and the fact that all the variables were nominal, it was decided to limit the organization of the results to frequencies and contingency tables. Some contrast tests were performed, including Chi square.

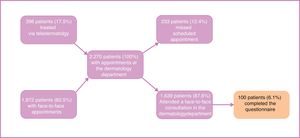

ResultsThe SampleThe questionnaire was answered by 134 patients, of whom 100 (74.6%) were attending the dermatology department and had previously been photographed by a dermatologist. The other 34 respondents (25.4%) were patients with appointments at the gynecology, traumatology, or gastroenterology departments and very few of them had prior experience of medical photography. The 100 dermatology patients represent 6.1% of the total number of patients who consulted that department during the study period.

During that period, 2,270 appointments were made by the dermatology department. Of these, 398 were handled via teledermatology and in 233 cases (10.3%) the patient did not attend. Of the remaining 1,639 patients (the 2,270 patients less those treated via teledermatology and those who missed their appointment), 100 (6.1%) submitted a completed questionnaire (Fig. 1). The hospital serves a reference population of approximately 64,000 inhabitants in a catchment area comprising the Alt Camp and Conca de Barberà regions in the Camp de Tarragona, areas where 18% and 24%, respectively, of the inhabitants are aged over 65 years.

The characteristics of the 134 respondents were as follows: 81 women (60.4%), 51 men (38.1%), and 2 (1.5%) individuals who did not specify their gender in answer to the question. The age distribution was about half under 55 years (49.3%) and half over 55 (50.7%). Individuals over 80 years of age accounted for 9.7% of the sample. Most of the respondents were married (63.4%) or living with a partner (14.2%). The majority reported having a primary school (26%) or vocational level (44%) education. The largest group of occupations reported (current or prior to retirement) were centered around the region's factories (factory workers and clerical staff); the second largest was agricultural work.

Almost all the respondents were born in Spain and they were mostly Catholics, although half of those who identified as Catholics declared themselves to be non-practicing. All of the participants lived in Valls or adjacent areas.

AttitudesThe usefulness of medical photography in general. The opinion that medical photography is useful was expressed by almost all of the participants (94.8%) irrespective of age, sex, educational level, occupation, or the hospital department they were visiting (Fig. 2). Most of those who did not consider photography to be useful were patients of departments other than dermatology. These differences were statistically significant (P < −.01).

In relation to specific uses. In total, 86.6% of the respondents were of the opinion that photographs would be useful in the diagnosis of their lesions. This high percentage of affirmative responses was maintained in respect of their usefulness in treatment follow-up (88.1%) and consultations with other doctors (86.6%). Fewer patients (74.6%) considered that photographs of their condition would be useful in the diagnosis of other people (Fig. 3).

The circumstances in which the patient was willing to authorize photography. The majority of patients said that they would consent to being photographed if they had malignant (88.8%) or extensive (85.1%) lesions. The percentage of positive responses dropped to 78.4% when patients were asked about facial lesions. Among women, this percentage was even lower, but most of those whose answer was not affirmative expressed their opinion in the form of doubts (“I do not know whether I would give my consent”). The percentage of respondents who said that they would consent to photography in the case of genital lesions was even lower (70.2%) (Fig. 4). Many of those who responded negatively to the question of consent in the case of a genital lesion expressed doubts (“I do not know whether I would give my consent”) rather than a flat refusal (“I would not give consent”); the percentages were almost equally distributed in men and women.

The question of who would take the photographs also gave rise to statistically significant differences: most respondents (95.5%) expressed a willingness to be photographed by the attending doctor and a smaller proportion said they would accept another doctor (64.9%) or a nurse (66.4%) (Fig. 5). In the case of a professional photographer, acceptance fell to 21.6% of patients. In pilot interviews, it was clear that patients did not consider the photographer to be an authority figure in the medical field.

The most interesting finding relating to religion was the response of 2 Muslim women with appointments at the dermatology department. The women were around 30 years of age, married, with children. While they made clear their distrust of photography in general, they nonetheless recognized the diagnostic value of medical photography and stressed that it should be a female doctor who took the photographs. They also insisted on the strict medical use of the images. The Muslim religion prohibits representations of the divine and the human.5

DiscussionThe results of our study reveal that most patients have a positive attitude towards being photographed by the attending physician, particularly in the case of malignant or extensive lesions. We found less acceptance in the case of facial and genital images and photographs taken by non-medical personnel.

Exploring Through PhotographyThe aim of exploratory studies is to collect initial data on the subject, usually in a nonrandomized sample and using nominal and ordinal variables and mainly descriptive statistics.4

The aim in this case was to explore factors that might influence patient attitudes, such as their beliefs and the medical circumstances, and to enquire about their intentions regarding consent. Given the complex nature of the emotional aspects involved, we did not address these directly but rather explored them through certain questions and the information collected during the pilot study. One of the findings of that exercise was the importance of the patients’ trust in the attending physician.

This trust encompasses both the doctor's professional skills and his or her respect for the patient. This respect was a key issue in one of the most significant concerns expressed by many patients about photography: the strictly professional use to which the patients trust their physician will put the images obtained.

Different people have different attitudes to being photographed. In general, doubts about consenting to photography and refusal of consent are related to an unwillingness to be identified in the photograph and a need to defend anonymity.

Equal numbers of men and women said that they would not consent to photography in the case of a genital lesion, a response that would appear to reflect the perception in our culture that the genitals engender modesty and are an intimate part of the body.

The high percentage of affirmative responses received when the question specified that the photographs would be taken by the patient's own doctor illustrates the emotional component involved: trust (the Spanish term confianza was used in the pilot interview) is the feeling that most influences the decision to consent to photography. By contrast, a feeling of distrust about the use photographs might be put to was the motive most often cited by patients who said that they would not consent to photography at a subsequent visit, that is, when a specific request was made; 10% of the patients expressed doubts about consenting to photography in a hypothetical future consultation because they “distrusted what use such photographs might be put to”. The majority (70%) of patients who expressed such doubts had no past experience of being photographed by their dermatologist. Prior experience appeared to make a difference.

ConclusionsThe results of our study showed that patients have a positive attitude toward being photographed for medical purposes, provided that the photographer is the attending physician, and particularly in the case of malignant lesions and in non-identifiable areas of the body. Our methods and findings are in line with those of Lau et al.,10 Wang et al.,11 Leger et al.,12 and Sikka.13

The attitudes to medical photography of the patients in our sample may have been positively biased because they belong to a population in which teledermatology has been in use for over 6 years and in which approximately 20% of patients are attended to via teledermatology using photographs. Our findings are, nonetheless, comparable to those of other authors.

Any study of attitudes towards medical photography will involve an evaluation of the beliefs, feelings, and intentions of the subject in relation to such photography and, ultimately, how they feel about allowing someone to photograph an area of their skin for medical purposes. Greater knowledge of patient attitudes provides us with insights into their fears and allow us to obtain clinical photographs in the context of a relationship based on respect for their beliefs.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pasquali P, Hernandez M, Pasquali C, Fernandez K. Actitudes de pacientes hacia la fotografía médica. Estudio en población española: Pius Hospital de Valls (Tarragona, España). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:131–136.