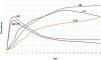

Atopic march (AM) reflects the sequential appearance of allergic phenomena in predisposed individuals. It typically begins in the first months of life with the onset of atopic dermatitis (AD), followed by later development in childhood of IgE-mediated food allergy (IgE-FA), allergic asthma (AA), allergic rhinitis (AR), and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) (Fig. 1).1 In most cases, AD constitutes the first step. Therefore, several authors have focused on AD as a key therapeutic target for preventing the AM.

Atopic march. Atopic dermatitis (AD) typically develops first, followed by IgE-mediated food allergy (IgE-FA), allergic asthma (AA), allergic rhinitis (AR), and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Source: authors’ own elaboration. AD: atopic dermatitis; IgE-FA: IgE-mediated food allergy; AA: allergic asthma; AR: allergic rhinitis; EoE: eosinophilic esophagitis.

In this article, we describe the results of a national multicenter survey conducted among dermatology residents and attending dermatologists in June 2023 on their knowledge and opinions about the AM. We also present a brief review of the literature centered on recent developments related to this entity.

Table 1 illustrates the survey results. A total of 178 participants completed the survey, of whom 159 (89.3%) were attending dermatologists, with the largest proportion being dermatologists with >25 years of clinical practice (37.1%). The autonomous communities with the highest participation were Madrid (n=39; 23%), followed by Andalusia (n=27; 16.6%), and Catalonia (n=24; 14.7%). Most respondents supported the existence of the AM (n=148; 83.2%) vs 12.9% who had doubts and 2.3% who did not believe in its existence. In addition, nearly 90% agreed that AD is frequently the first sign of the AM. When asked about contributing factors in the AM, the most frequently cited were genetic factors (n=166; 93.3%), followed by environmental (n=163; 91.6%) and immunologic factors (n=150; 84.3%). More than half of respondents (56.2%; n=100) supported the use of preventive measures in young children with AD to reduce the risk of developing additional components of the AM. The most widely endorsed preventive measures were emollients (64%), avoidance of tobacco exposure (53.4%), and topical corticosteroids (43.8%). On the other hand, in infants without AD but at risk of developing it, 53.9% (n=96) supported the use of preventive measures. In this scenario, the most frequently endorsed interventions were emollients with lipid combinations (73%), avoidance of tobacco and environmental pollution (68.1%), and breastfeeding (67.5%). Approximately two-thirds of respondents believed that greater AD severity increases both the likelihood and severity of AM signs. Finally, nearly all respondents (n=157; 96.3%) agreed that dermatologists should play a central role in the management of AD and, when necessary, be responsible for referral to other specialists (allergists, pulmonologists, etc.). Since AD precedes other AM components, preventing AD—and, when present, initiating early treatment—may serve as a strategy to prevent the AM. Table 2 illustrates the main studies proposing methods to reduce AD or the AM.2–5

Results of the national survey on the atopic march. Source: data from the national aborDA project survey, conducted between June 20th and June 30th, 2023.

| Question | Options | N (total=178) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. You are a… | Dermatologist with >25 years of practice | 66 | 37.1 |

| Dermatologist with 15–25 years of practice | 39 | 21.9 | |

| Dermatologist with 5–15 years of practice | 38 | 21.4 | |

| Dermatologist with <5 years of practice | 16 | 9.0 | |

| Dermatology resident | 19 | 10.7 | |

| Q2. In which autonomous community do you currently work? | Andalusia | 27 | 16.6 |

| Aragon | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Balearic Islands | 7 | 4.3 | |

| Canary Islands | 5 | 3.1 | |

| Cantabria | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Castile–La Mancha | 6 | 3.7 | |

| Castile and León | 7 | 4.3 | |

| Catalonia | 24 | 14.7 | |

| Community of Madrid | 39 | 23.9 | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 17 | 10.4 | |

| Extremadura | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Galicia | 8 | 4.9 | |

| Basque Country | 11 | 6.8 | |

| Principality of Asturias | 3 | 1.8 | |

| Region of Murcia | 4 | 2.5 | |

| La Rioja | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 0 | 0 | |

| Q3. Do you have a pediatric dermatology specialty clinic? | Yes | 49 | 30.1 |

| No | 114 | 69.9 | |

| Q4. Do you believe in the existence of the atopic march? | Yes | 148 | 83.2 |

| No | 4 | 2.3 | |

| Unsure | 23 | 12.9 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Q5. Which of the following factors do you believe may influence the development of the atopic march? (Multiple answers allowed) | Genetic factors | 166 | 93.3 |

| Immunologic factors | 150 | 84.3 | |

| Environmental factors | 163 | 91.6 | |

| Oxidative free radicals | 37 | 20.8 | |

| Other | 6 | 3.4 | |

| Q6. Which of the following statements do you agree with the most? | Atopic dermatitis is always the first sign of the atopic march | 5 | 2.8 |

| Atopic dermatitis is frequently the first sign of the atopic march | 160 | 89.9 | |

| Atopic dermatitis generally appears after food allergy, rhinitis, or asthma | 13 | 7.3 | |

| Q7. In young children with atopic dermatitis, do you recommend any measures to prevent other atopic march-related conditions? | Yes | 100 | 56.2 |

| No | 78 | 43.8 | |

| Q8. Which of the following do you believe could act as preventive measures for other atopic march processes in patients with atopic dermatitis? (Multiple answers allowed) | Emollients | 114 | 64.0 |

| Topical corticosteroids | 78 | 43.8 | |

| Oral corticosteroids | 20 | 11.2 | |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | 75 | 42.1 | |

| Anti-IL-4/13 antibodies | 66 | 37.1 | |

| Anti-IL-13 antibodies | 40 | 22.5 | |

| Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors | 41 | 23.0 | |

| Prebiotics | 33 | 18.5 | |

| Probiotics | 49 | 27.5 | |

| Early food introduction | 48 | 27.0 | |

| Avoidance of tobacco exposure | 95 | 53.4 | |

| Water softeners | 8 | 4.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 3.9 | |

| None of the above | 16 | 9.0 | |

| Q9. In infants at risk of developing atopic dermatitis, should preventive measures be applied in the first weeks or months of life? | Yes | 96 | 53.9 |

| No | 11 | 6.2 | |

| Unsure | 71 | 39.9 | |

| Q10. Which of the following could act as preventive measures for the atopic march in infants at risk of atopic dermatitis? (Multiple answers allowed) | Petrolatum-based emollients | 33 | 20.3 |

| Emollients with lipid combinations (ceramides, cholesterol, fatty acids) | 119 | 73.0 | |

| Prebiotics | 38 | 23.3 | |

| Probiotics | 46 | 28.2 | |

| Early food introduction | 47 | 28.8 | |

| Breastfeeding | 110 | 67.5 | |

| Avoidance of tobacco and air pollution | 111 | 68.1 | |

| Pet exposure | 60 | 36.8 | |

| Water softeners | 9 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.8 | |

| None of the above | 11 | 6.8 | |

| Q11. Do you believe that the severity of atopic dermatitis is related to later incidence of food allergy, allergic asthma, or allergic rhinitis? | Yes | 117 | 71.8 |

| No | 46 | 28.2 | |

| Q12. Do you believe that the severity of atopic dermatitis is related to later severity of food allergy, allergic asthma, or allergic rhinitis? | Yes | 99 | 60.7 |

| No | 61 | 37.4 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.8 | |

| Q13. Should dermatologists play a central role in managing atopic dermatitis and, when necessary, refer patients for joint management with other specialists? | Yes | 157 | 96.3 |

| No | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Unsure | 4 | 2.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.6 | |

Q, question; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase.

Main studies proposing methods to reduce atopic dermatitis or the atopic march. Source own elaboration.

| Proposed measure | Evidence | N | Proposed mechanism of action | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emollients | Phase 3 clinical trials (results from 3 trials) | 1394 | Skin barrier restoration | Daily emollient use in high-risk newborns reduced AD prevalence at age 3 years | Chalmers et al. |

| Prospective study | 160 | Skin barrier restoration | No significant differences in AD incidence rate at age 2 between high-risk newborns treated with emollients vs placebo | Kottner et al. | |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis | 11 studies, >10,000 patients | Skin barrier restoration | Early emollient application is effective for preventing AD in high-risk infants; emulsions are the optimal vehicle | Liang et al. | |

| Prebiotics | Prospective study | 459 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Use of synbiotics and/or emollients within the first year of life did not reduce incidence rate of AD or FA | Dissanayake E et al. |

| Probiotics | Prospective study | 459 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Use of synbiotics and/or emollients within the first year of life did not reduce incidence rate of AD or FA | Dissanayake E et al. |

| Phase 1/2 clinical trial | 15 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Topical Roseomonas mucosa significantly reduced AD severity, topical steroid use, and S. aureus colonization | Myles I et al. | |

| Feeding, early food introduction, and breastfeeding | Prospective cohort | 4089 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Breastfeeding>4 months reduced AD and other AM outcomes at age 4 years | Kull I et al. |

| Prospective cohort | 2252 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | When breastfeeding is not possible, the use of hydrolyzed formulas in infants aged 0–4 months reduces the incidence of AD (whey and casein hydrolysates) and of allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma (casein hydrolysates). | Von Berg A et al. | |

| Real-world clinical trial | 640 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | In children at risk for AD, early (before 11 months of age) and regular peanut consumption through 6 years of life decreases the prevalence of this allergy. | Du Toit G et al. | |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis | 27 prospective studies, >10,000 patients | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | No association was found between AD and breastfeeding. However, in patients with an atopic genetic predisposition, exclusive breastfeeding may offer a protective benefit vs the development of AD | Lin et al. | |

| Avoidance of tobacco, pollution, and climate factors | Prospective study | 100,303 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Cold temperatures, low humidity, and low atmospheric pressure increased AD incidence rate | Yokomichi et al. |

| Retrospective study | 53,505 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Pre- and post-natal smoking significantly increased risk of AD and allergic asthma | Yoshida S et al. | |

| Pet exposure | Meta-analysis | >10,000 patients | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Cat exposure slightly protective for asthma; dog exposure, on the other hand, slightly increases asthma; no effect on allergic rhinitis | Takkouche B et al. |

| Cohort study | 84,478 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Dog exposure slightly protective for AD and asthma; bird exposure slightly increases asthma | Pinot de Moira A et al. | |

| Immunotherapy | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 15 RCTs with 2703 patients | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | Not conclusively effective for preventing the AM; small benefit in reducing asthma in patients with allergic rhinitis | Paller AS et al. |

| Water softeners | Prospective study | 1303 | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | In children with filaggrin mutations, hard-water exposure increased AD risk×3; softeners may help | Jabbar-López JK et al. |

| Vitamin D | Systematic review | 1 RCT+3 uncontrolled studies | Cutaneous homeostasis regulation | The evidence supporting sun exposure or vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of atopic dermatitis and other atopic signs is limited; therefore, these measures should not currently be recommended. | Yepes-Nuñez JJ et al. |

| Topical corticosteroids | Prospective study | 74 | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Topical corticosteroid therapy normalized cytokine signatures in the peripheral blood of children with AD, suggesting a protective role vs other features of the atopic march. | McAleer MA et al. |

| Oral corticosteroids | — | — | — | No studies have evaluated the prevention of the atopic march with oral corticosteroids. Moreover, these agents may exacerbate disease flares. | Drucker AM et al. |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | Prospective study | 1091 | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Pimecrolimus did not reduce AD or AM signs vs placebo | Schneider L et al. |

| Anti-IL-4/13 antibodies | Clinical trial meta-analysis | 2296 dupilumab; 1229 placebo | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Dupilumab significantly reduced allergic events; may help block the AM | Geba G et al. |

| Anti-IL-13 antibodies | Phase 2 trial | 224 | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Tralokinumab did not significantly reduce eosinophilic inflammation in the bronchial lamina propria, blood, or sputum compared with placebo, although it did lower FeNO and IgE levels. These findings suggest that IL-13 is not a key driver of airway inflammation. | Russell RJ et al. |

| JAK inhibitors | Narrative review | Not defined | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | A pathophysiological review proposing JAK inhibitors as a potential preventive therapeutic strategy for the atopic march. Real-world studies are still lacking. | Hee Kim Kim J et al. |

| Anti-IgE antibodies | Real-world clinical trial | Not defined | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Assessment of asthma development in high-risk patients aged 2–4 years on omalizumab at standard doses for 2 years, followed by an additional 2-year observation period. Results are not yet available. | Phipatanakul W et al. |

| Anti-TSLP antibodies | Phase 2 trial | 251 | Reduction of cutaneous immune response | Target EASI not achieved on week 12; mechanism suggests possible role in AM prevention | Spergel J et al. |

| Holistic educational prevention programs | Real-world clinical trial | 2226 | Multidisciplinary intervention on various aspects of the etiopathogenesis of AD | Study designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a holistic prevention program (educational, pharmacologic, etc.) for atopic dermatitis in Chinese mothers. Results are not yet available. | Zhao M et al. |

AD: atopic dermatitis; IL: interleukin; Ig: immunoglobulin; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Therefore, according to the results of our survey, the main measures to limit AD and the AM would be emollients, breastfeeding, and avoidance of tobacco smoke. Evidence regarding emollients for preventing the AM is contradictory.2,3 In contrast, several studies support breastfeeding and tobacco avoidance for AM prevention.3,4 Regarding other potential preventive strategies, there is uncertainty on the utility of probiotics and prebiotics, early pet exposure, immunotherapy, or topical calcineurin inhibitors.6 These variable findings mirror our survey results, in which only 20–40% of respondents indicated they would use probiotics, prebiotics, topical or oral corticosteroids, or biologic therapies targeting IL-4 or IL-4/13 to prevent the AM.

We are currently in a period of rapid expansion in knowledge related to the pathophysiology of AD and the AM. This knowledge has led to the development of new therapeutic targets (Supplementary Table 1).8 The next major challenge is the ability to determine each patient's specific genotype and, consequently, to select individualized therapies.7 It is anticipated that such targeted treatment will reduce AD and the associated processes of the AM.

In conclusion, most Spanish dermatologists believe in the existence of the AM and support the need for early preventive interventions. The main preventive measures identified were “plus” emollients, breastfeeding, and avoidance of tobacco exposure.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, and especially Montse Tort (Grupo Mayo), for their support in conducting and disseminating the survey included in this article.