Nail involvement in psoriasis is common. It is seen in up to 80% of patients with psoriatic lesions and may be the only manifestation in 6% of cases. Nail psoriasis is correlated with more severe disease, characterized by earlier onset and a higher risk of psoriatic arthritis. Accordingly, it can also result in significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life. Psoriasis involving the nail matrix causes pitting, leukonychia, red lunula and nail dystrophy, while nail bed involvement causes splinter hemorrhages, onycholysis, oil spots (salmon patches), and subungual hyperkeratosis. Common evaluation tools are the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), the modified NAPSI, and the f-PGA (Physician's Global Assessment of Fingernail Psoriasis). Treatment options include topical therapy, intralesional injections, and systemic and biologic agents. Treatment should therefore be assessed on an individualized basis according to the number of nails involved, the part of the nail or nails affected, and the presence of concomitant nail and/or joint involvement.

La psoriasis ungueal puede afectar al 80% de los pacientes con psoriasis cutánea y puede ser la única manifestación en el 6% del total. Además, se correlaciona con una enfermedad psoriásica más grave, con un inicio más precoz y con una mayor probabilidad de desarrollar artritis psoriásica. Todo ello hace que se asocie a un importante deterioro funcional y a una disminución de la calidad de vida. La psoriasis ungueal que afecta la matriz puede causar piqueteado/pitting, leuconiquia, manchas rojas en la lúnula o distrofia de la lámina, mientras que la afectación del lecho causa hemorragias en astilla, onicólisis, manchas de aceite o salmón e hiperqueratosis subungueal. Los métodos de evaluación comunes son las escalas NAPSI, NAPSI modificada o f-PGA. Actualmente, disponemos de tratamientos tópicos, intralesionales, sistémicos y biológicos, por lo que deberá individualizarse según el número de uñas implicadas, la zona ungueal afectada y la presencia de afectación cutánea y/o articular.

Nail involvement is very common in psoriasis, with prevalence rates ranging from 47.4% to 78.3% depending on the study.1–3 Nail bed and nail matrix psoriasis have a wide range of clinical manifestations, including pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and nail plate discoloration.4 Severe nail disease and functional impairment can have a significant impact on patient quality of life. Nail psoriasis is generally considered to be difficult to treat because the nail plate is a densely keratinized hydrophilic gel structure, which while resistant, can impede the penetration of topical agents, which as a consequence often have little effect.5 In addition, intralesional injections in the area of the nail matrix or bed are painful and can cause complications, while responses to systemic therapies are often insufficient. Overall, thus, the treatment of nail psoriasis is challenging.

In this narrative review we discuss the clinical characteristics of nail psoriasis and examine the treatments available. We conducted a literature search of PubMed from the start of the database using the terms “nail psoriasis” AND “treatment OR therapy” and the names of the different treatments discussed in the manuscript.6 We reviewed all articles in English addressing the treatment of nail psoriasis as the main subject that had been published in peer-reviewed journals. We included some additional articles identified by hand searching the references of review articles identified. We then collected and organized relevant data and performed a narrative synthesis.

EpidemiologyThe prevalence of nail psoriasis varies widely, with reported rates ranging from 6.4% to 81.8%.1–4,7–9 It is difficult thus to determine its true prevalence. Most studies of the prevalence of nail psoriasis have been conducted within broader studies of patients with cutaneous psoriasis; studies focusing on exclusive nail involvement have reported a prevalence rate of 6%.4 Nail psoriasis affects male patients more frequently and the most common clinical manifestation is pitting.4 This form of psoriasis is also associated with earlier onset of cutaneous psoriasis.9 According to some reports, patients with cutaneous and nail psoriasis are 10% more likely to have a family history of this disease.2 Nail involvement has also been found to correlate with psoriasis duration and severity and to be associated with an increased risk of psoriatic arthritis (PsA).2 Childhood nail psoriasis has a reported prevalence of between 17% and 38% and most studies have found a link with more severe disease.8,10

Etiology and PathogenesisPsoriasis is a multifactorial systemic disease involving different genetic and environmental factors.11 Several alleles for susceptibility to psoriasis have been identified. HLA Cw0602 is the most widely studied and accounts for 50% of disease heritability.12 That said, nail psoriasis is less common in carriers of this haplotype.2,12,13 The genetic basis of the different clinical subtypes of psoriasis has not been fully elucidated and no clear genetic causes have been identified for nail involvement. Some authors have detected a localized variant in IL1RN, which encodes the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1A, which can cause nail changes. It might thus have a role in the development of nail disease in patients with cutaneous psoriasis.14 More recent studies, however, have indicated that nail and joint involvement in psoriasis might be related to tissue-specific factors, such as biomechanical stress and microtrauma, which would trigger the activation of aberrant innate immune responses.15,16

Comorbidities and Associated FactorsPsoriatic ArthritisPsA is the most common comorbidity in psoriasis, with a prevalence of approximately 20%.16 Patients with PsA are more likely to have nail involvement than those with cutaneous psoriasis.4,17 An estimated 80% to 90% of patients with PsA will develop nail psoriasis.2,4,17

The association between subclinical enthesopathy and nail disease is explained by the anatomic proximity between the extensor tendon of the distal phalanx and the nail matrix.18 Most authors agree that nail involvement is predictive of enthesitis, which is associated with early-stage PsA.18–22 Proper diagnosis and treatment of nail psoriasis is thus important as it could potentially delay the onset of joint disease.23

OnychomycosisCertain clinical features of nail psoriasis, such as hyperkeratosis and onycholysis, are seen in a number of nail disorders. It can thus be challenging to differentiate between nail psoriasis and onychomycosis. In addition, an estimated 30% of patients with psoriatic nail disease have concomitant onychomycosis,24 and some authors have found onychomycosis to be more common in psoriasis patients with nail involvement.25 It has been postulated that the nail deformations observed in psoriatic nails might be predisposing factors for onychomycosis and that onychomycosis might trigger the development of nail psoriasis (Koebner phenomenon).25,26

Fungal cultures are usually only performed in patients with concomitant cutaneous and nail psoriasis when obvious clinical changes are observed.27 As onychomycosis and nail psoriasis often coexist, some authors recommended checking for onychomycosis before starting a patient on psoriasis treatment, especially if they need immunosuppressants, as these could aggravate any existing infection.26,28 Fungal cultures could perhaps be included in clinical guidelines for the treatment and management of nail psoriasis,28 although they do have some significant limitations (time and false negatives). Alternative tests include direct microscopic examination with potassium chloride (sensitivity of 61%), histologic examination (88.4%), and a combination of both (94%).29 PCR-based molecular diagnostic tests offer very high sensitivity (97%) but are not yet widely available.30,31 Likewise, some centers use a rapid diagnostic test based on an immunochromatographic assay that can detect Trichophyton antigens in nail samples and offer immediate results.32

SmokingSmoking is a known independent risk factor for psoriasis33 and its possible associations with nail psoriasis have been studied. Temiz et al.34 recently showed that psoriasis patients were significantly more likely to have nail psoriasis when they smoked and they also reported a greater need for systemic therapy among smokers.

Clinical PresentationIn most patients, nail psoriasis appears at the same time as or after cutaneous psoriasis. On occasions, however, it is the only manifestation of disease.4,35

The clinical presentations of nail psoriasis vary according to the affected area.35 Susceptible areas are the nail bed, the nail matrix, the hyponychium, and the nail folds (Table 1).23

Description of Clinical Features of Nail Psoriasis According to Affected Area.

| Area | Clinical feature |

|---|---|

| Nail matrix | Pitting: punctuate depressions in nail plateLeukonychia: white discoloration of nail plateRed spots in the lunula: pink-red dots in the lunulaCrumbling: brittleness and disintegration of the nail plateBeau lines: horizontal groovesTrachyonychia: rough nails with a dull appearance due to the presence of abundant longitudinal ridges and punctuate depressions. |

| Nail bed | Splinter hemorrhages: linear areas of bleeding visible through the nail plateOnycholysis: distal separation of the nail plate from the nail bed.Oil dots: irregular yellowish or salmon-colored areas, also called salmon stainsSubungual hyperkeratosis: accumulation of gray-white keratin between the nail bed and nail plate. |

| Hyponychium | Onychorrhexis: longitudinal ridging and distal splitting of nail plate. |

| Nail fold | Paronychia: inflammation of the periungual tissues.Acropustulosis: pustules that may coalesce around the nails |

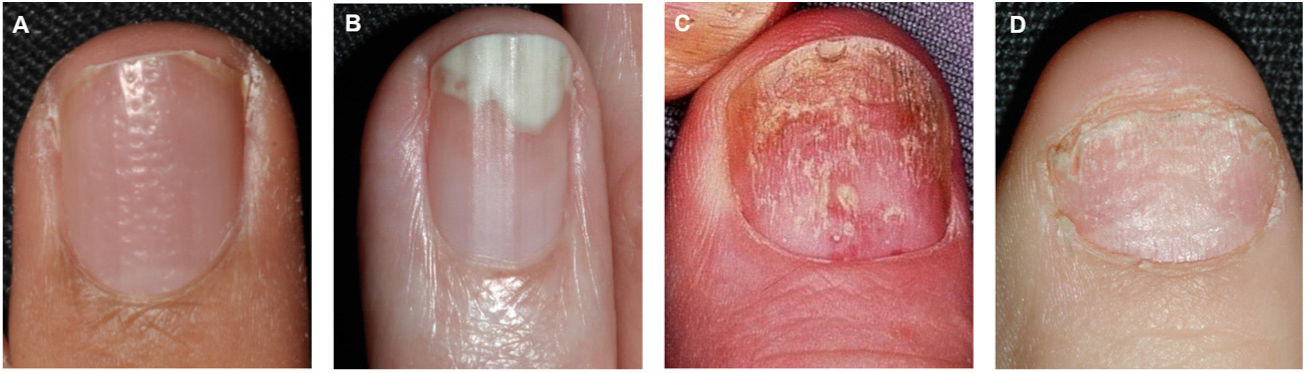

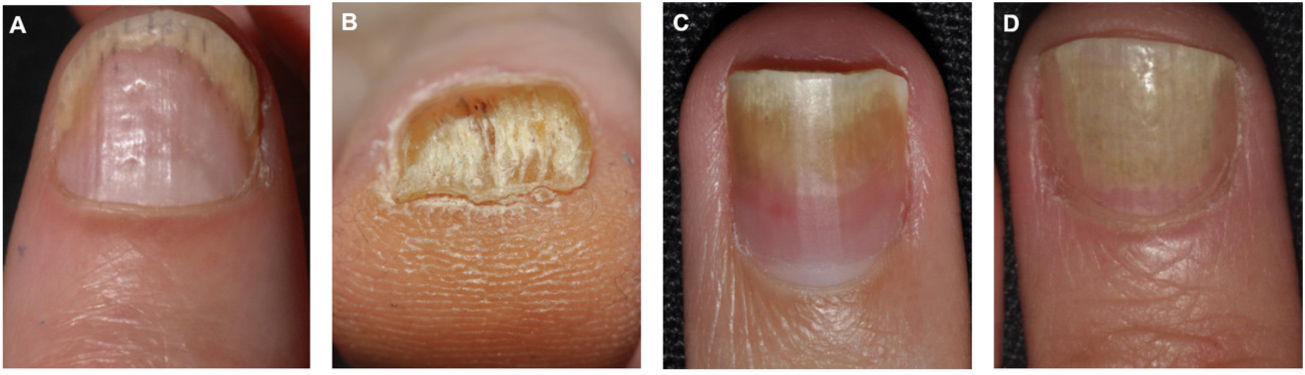

Pitting is the most common clinical feature of nail matrix psoriasis.23 Pitting refers to the presence of irregular depressions in the nail plate that histologically correspond to foci of parakeratosis.36 The more severe the psoriasis, the more pits are seen.37 Pitting is a characteristic feature of nail psoriasis, but it also occurs in patients with alopecia areata or eczema; in psoriasis, however, the pitting is normally deeper and more irregular.36 Other characteristic features of nail matrix psoriasis are leukonychia, red spots in the lunula, crumbling or complete nail plate dystrophy, and trachyonychia (Fig. 1).38

Clinical Features of Nail Bed PsoriasisNail bed psoriasis is clinically characterized by splinter hemorrhages (damaged capillaries), onycholysis with a proximal yellow-orange border, oil dot or salmon patch discoloration, and subungual hyperkeratosis (Fig. 2).38–40 Hyperkeratotic skin will often acquire a pearl white or yellow color due to the accumulation of glycoproteins; a green or brown color would be indicative of a secondary bacterial and/or fungal infection.38 Other clinical manifestations are onychorrhexis and Beau lines.38–40 Paronychia or acropustulosis may be seen in patients with nail fold involvement.

Site of InvolvementFingernails are more likely than toenails to be affected by psoriasis, and the most common digits involved are the fourth finger and the first toe.41 The clinical features vary according to site of involvement. Pitting is typical in fingernail psoriasis, while hyperkeratosis and onycholysis are more common in toenail psoriasis.41

Histopathologic FindingsThe classic histopathologic findings of nail psoriasis are the same as those seen in cutaneous psoriasis and include mild to moderate hyperkeratosis, foci of parakeratosis, epidermal psoriasiform hyperplasia, dilated tortuous capillaries in the papillary dermis, and neutrophil infiltrates.42 Spongiosis and accumulation of serum-like exudates are more common in psoriasis involving the nails. Additional findings include loss of the granular layer in the hyponychium and hypergranulosis in the nail bed and nail matrix.4,42 The matrix epithelium underlying the intraungual parakeratosis tends to be unaltered, but mild spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils may be seen.

Assessment of Nail Psoriasis SeverityNail psoriasis severity is assessed by analyzing clinical features and extent of disease. A number of scales have been developed to facilitate standardized assessment. The Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) (Table 2) is the most widely used scale,43 but other options, used mainly in clinical trials, are the modified NAPSI and the fingernail physician global assessment.44,45

Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI).

| Nail matrix psoriasis (0 or 1) | Nail bed psoriasis (0 or 1) |

|---|---|

| Pitting | Onycholysis |

| Leukonychia | Oil drop |

| Red spots in the lunula | Splinter hemorrhages |

| Nail plate crumbling | Nail bed hyperkeratosis |

| Extent of involvement of nail psoriasis (in nail matrix and nail bed) | Sum of scores |

|---|---|

| 0=None | Single nail=0–8 |

| 1=present in 1 of 4 quadrants | All fingernails=0–80 |

| 2=present in 2 of 4 quadrants | All toenails=0–80 |

| 3=present in 3 of 4 quadrants | Total NAPSI score=0–160 |

| 4=present in 4 of 4 quadrants |

Each nail is given a separate score for nail matrix psoriasis and nail bed psoriasis (the presence of 1 feature is scored a maximum of 1). The nail is then divided into 4 quadrants, each of which is scored independently for nail matrix psoriasis (score of 0–4) and nail bed psoriasis (score of 0–4). The final score is obtained by adding up the individual scores.

Assessment of nail psoriasis is mainly clinical, but it can be challenging because of overlapping symptoms with other nail disorders. Additional tests to support diagnosis and follow-up are readily available in dermatology clinics.

DermoscopyDermoscopy is a noninvasive imaging test available to most dermatologists, and its usefulness as a diagnostic and follow-up tool in nail psoriasis has been demonstrated. Dermoscopy applied to nail diseases is known as onychoscopy. A number of dermoscopic findings have recently been correlated with disease severity in nail psoriasis.46–48 The main findings are splinter hemorrhages, pitting, distal onycholysis, increased density of dilated capillaries in the hyponychium and proximal fold, nail plate thickening and crumbling, subungual hyperkeratosis, trachyonychia, Beau lines (horizontal grooves), and oil drops. Onychoscopy is particularly useful for assessing mild disease with simple onycholysis or isolated nail bed hyperkeratosis, as it enables visualization of the hyponychial capillaries.46,48 In short, onychoscopy is useful for diagnosis, differential diagnosis (checking for onychomycosis), and monitoring of treatment responses.

UltrasoundAn increasing number of studies in recent years have demonstrated that ultrasound is a very useful tool for assessing nail psoriasis. It is simple, painless, and quick. Ultrasound provides a detailed view of the nail unit (plate, matrix, bed, and lateral, proximal, and distal folds) and can also be used to assess underlying or adjacent structures, such as bone and tendons. Proper training in its use, however, is necessary. High-frequency linear probes (15–22MHz) can help detect submillimetric lesions (and even subclinical changes). The most common ultrasound findings in nail psoriasis49–54 are summarized below.

Nail plate changes. Focal hyperechoic involvement of the ventral plate, with a loss of definition. Surface depressions corresponding to pitting. Reduced intermediate hypoechoic space with homogeneous thickening of the plate. Wavy nail plate, with a hyperechoic, destructured appearance.

Nail bed and matrix changes. Thickening of matrix and increased distance between the ventral nail plate and the distal phalanx. A cutoff of 2mm has been found to differentiate between patients with psoriasis/PsA and controls with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 71%.

Microvascularization changes. Doppler imaging shows increased general flow and an increased resistance index in the nail fold vessels.

Differential DiagnosisClinical manifestations similar to those seen in nail psoriasis can be caused by a range of infectious, autoimmune, and idiopathic diseases and trauma. A thorough clinical history and examination of all 20 nails is essential for reaching a correct diagnosis. Patients should be questioned about their personal and family history of psoriasis, previous episodes of arthritis or enthesitis, and the possibility of repeated microtrauma. The different entities that should be contemplated in the differential diagnosis are shown in Table 3.35,48,55,56,57

Main Entities to Consider in the Differential Diagnosis According to Clinical Features.

| Clinical feature | Differential diagnosis and diagnostic clues |

|---|---|

| Pitting | Psoriasis: patient younger than 20 y and deep depressionsAlopecia areata: small, superficial, regular depressionsEczema: thick, irregular depressions associated with horizontal groovesIdiopathic: isolated depressions |

| Onycholysis | Psoriasis: erythematous border around the onycholytic areaIdiopathic: female patients exposed to excessive moisture in this areaOnychomycosis: jagged proximal border around onycholytic area with spikes, opaque spots, and longitudinal white, yellow, or brown striaeExternal cause (e.g., manicure, hairdressing): irregular border and bleeding |

| Subungual hyperkeratosis | Psoriasis: white-silver discolorationOnychomycosis: accompanied by longitudinal striae and altered ventral area of the distal nail plateEczema: accompanied by pulpitis and usually affects the first 3 fingers of the dominant hand. |

| Splinter hemorrhages | Psoriasis: distalTraumatic cause: distal and accompanied by subungual hematomas and possible nail lossSystemic diseases (endocarditis, renal or pulmonary disease, vasculitis): proximal and painful |

| Oil drop | Quite characteristic of nail psoriasis |

| Red spots in the lunula | Quite characteristic of nail psoriasis, but may be seen in alopecia areata and lichen planus |

Management of cutaneous and nail psoriasis has improved in recent years thanks to the development of highly effective drugs with lasting results.58,59 Treatment and management decisions should be taken on a case-by-case basis depending on the number of nails affected, the concomitant presence of cutaneous or joint disease, comorbidities, and impact on quality of life. In general, patients should be advised to keep their nails short, avoid manicures and nail biting, wear protective gloves for manual tasks, and avoid contact with irritants.

Topical TreatmentFew quality studies have evaluated or compared topical treatments for nail psoriasis. In general, vehicles with a more oily composition (creams or ointments) applied under occlusion will achieve better results. The topical agent should be applied to the area of the proximal fold in patients with nail matrix psoriasis (Table 2). Nail bed manifestations should be treated by applying the product as close to the bed as possible, after clipping the onycholytic nail and scraping with a curette.35 The topical treatments available are described below.

Corticosteroids. There are no standardized recommendations on which topical corticosteroid regimen to use in nail psoriasis. In common practice, however, high-potency corticosteroids are applied under occlusion for long periods of time. Better outcomes have been observed for psoriasis affecting the nail matrix compared with the bed. The risk of distal phalanx atrophy and disappearing digit secondary to prolonged use must be borne in mind.35,60–63

Vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol, tacalcitol, calcipotriol). Vitamin D derivatives are effective when used as monotherapy or combined with topical corticosteroids (clobetasol nail lacquer or topical betamethasone). They appear to be more effective against damage to the nail bed than the matrix.60,64–66

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus). Tacrolimus has been shown to be an effective treatment for both nail bed and nail matrix psoriasis.67

Tazarotene. Tazarotene under occlusion appears to be effective in nail bed disease, but its use may be limited by the frequent occurrence of erythema, scaling, irritation, and paronychia.68–70

Intralesional TreatmentCorticosteroids. Corticosteroids are the only intralesional treatments that have shown acceptable results in nail psoriasis, and they can be injected into the nail matrix or nail bed. They should be injected using a 28–30G needle and a local analgesic to minimize intra- and postprocedural pain (main adverse effect). The agent should preferably be injected into the dermis of the lateral nail folds using a proximal approach when treating the nail matrix and a more distal approach when treating the nail bed. The most widely used regimen is an injection of approximately 0.4mL of triamcinolone acetonide at a concentration of 10mg/mL, although numerous protocols exist.35,71–74

Nonpharmacological TreatmentsA range of nonpharmacological treatments have been used for nail psoriasis and include phototherapy,75–77 photodynamic therapy,78 superficial radiotherapy,79 Grenz ray therapy,80 and laser therapy.78,81–83 These treatments are not recommended in routine clinical practice as they have shown highly variable results.

Systemic TherapySystemic agents are the treatment of choice for patients with psoriasis involving multiple nails or with nail psoriasis in addition to cutaneous or joint manifestations. Few randomized clinical trials have provided evidence to support specific recommendations on the use of systemic drugs in nail psoriasis. Information is available on the following drugs.

Retinoids (acitretin). Retinoids have shown moderate effectiveness in nail psoriasis, with a 40% to 50% improvement in NAPSI. The doses are lower than those used in cutaneous psoriasis (0.2–0.3mg/kg/d). Retinoids have a slow mechanism of action, but can be used for years. The most common adverse effects are cheilitis and scaling.76,84–86

Methotrexate. Methotrexate seems to be the most useful treatment for nail matrix psoriasis. It has shown moderate effectiveness, with a 40% to 50% improvement in NAPSI. The doses are the same as those used in cutaneous psoriasis. Comparisons to date have consistently shown methotrexate to be less effective than biologic agents.76,84,87,88

Cyclosporine. Cyclosporine is useful for the treatment of both nail bed psoriasis and nail matrix psoriasis. It is effective as monotherapy, but produces even better results when combined with calcipotriol. Its use is limited to about 12 months due to the risk of kidney damage.76,87,89–91

Apremilast. Apremilast was effective against both nail matrix psoriasis and nail bed psoriasis in clinical trials seeking authorization for the use of this drug; it showed a 60% improvement in NAPSI at 52 weeks.92–95

Biologic TherapiesA large number of biologic drugs have produced primary and secondary responses in nail psoriasis. Response tends to be slower than with cutaneous psoriasis, with visible improvements generally observed from week 12 onwards. Fingernails improve sooner than toenails because of their faster growth. Patients with more favorable cutaneous-joint responses also show better nail responses. Nonetheless, improvements in nail psoriasis following treatment with a biologic agent have not been shown to be independent of the presence or absence of PsA.76,96 The biologics that have been studied in nail psoriasis are described below.

Infliximab. Several studies have shown infliximab to be effective against both nail bed psoriasis and nail matrix psoriasis. Patients with more severe disease achieved greater and faster improvements than those with mild disease. Infliximab was also associated with improved quality of life scores.97–100

Adalimumab. Multiple studies, including clinical trials and cohort studies, have studied the use of adalimumab in nail psoriasis. The overall results have been good, with 55% to 95% reductions in NAPSI scores. The improvements were also independent of previous treatment with infliximab or etanercept.77,101–103

Etanercept. Etanercept has been associated with improved quality of life and reductions in NAPSI of between 50% and 90% in routine practice and observational studies.103–105

Ustekinumab. Ustekinumab is an effective treatment for nail bed and nail matrix manifestations, with a 57% to 97% reduction in NAPSI. It has also been found to improve patient quality of life.106–108

Secukinumab. According to recent results, secukinumab sustained its efficacy in nail psoriasis after a period of 2.5 years, with mean NAPSI improvement standing around 70% and sustained improvements in quality of life.109

Ixekizumab. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of ixekizumab in nail psoriasis, with complete response rates (100% reduction in NAPSI) of 55%.110–112

Brodalumab. A number of studies, including randomized clinical trials, have reported promising results for the use of brodalumab in nail psoriasis, with 64% of patients achieving a NAPSI score of 0 at week 52.113,114

Guselkumab. Guselkumab was authorized as a treatment for cutaneous psoriasis in Spain in 2019. Few studies have analyzed its use in nail psoriasis, but in the clinical trials that led its approval in cutaneous psoriasis, it showed better reductions in NAPSI compared with placebo at week 16.115

Risankizumab. Compared with placebo, risankizumab showed significantly greater improvements in NAPSI at weeks 16 and 52 in clinical trials.116

A recent network meta-analysis compared the efficacy of 6 biologics based on the results of 7 clinical trials. The analysis included patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and concomitant nail psoriasis, and the primary endpoint was complete resolution of nail psoriasis (NAPSI, modified NAPSI, or Physician Global Assessment of 0) at week 24–26. Ixekizumab was associated with the greatest likelihood of achieving complete response (46.5%), followed by brodalumab (37%), adalimumab (28.3%), guselkumab (27.7%), ustekinumab (20.8%), and infliximab (0.8%).59

ConclusionsNail psoriasis correlates with more severe psoriasis, earlier onset, and an increased risk of PsA. Accordingly, it is more likely to be associated with functional impairment and reduced quality of life. Its clinical presentations are highly variable. Diagnosis can be challenging, but ultrasound and dermoscopy provide a valuable aid in raising or confirming clinical suspicion. The current spectrum of treatments is broad and includes topical, intralesional, systemic, and biologic drugs. Treatment should be tailored to each case.

Authors’ ContributionsDr. Canal-García and Dr. Bosch-Amate contributed equally to this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.