Cocaine consumption has been increasing around the world in recent years and the associated complications are thus becoming more and more common.1 Levamisole is often found in contaminated cocaine and can increase the length and intensity of the stimulant effect of this recreational drug.2,3

Case descriptionA 47-year-old man with no medical background of note attended the dermatology department for a 1-month history of painful skin lesions on both ears. He otherwise felt well. On further questioning, he denied having taken any new or different prescription drugs and reported no prodromal symptoms. However, he did state he was a smoker and a user of cocaine since the age of 25 years; of note, he had sniffed cocaine 3 days before the onset of the lesions.

At presentation, symmetrical, bilateral erythematous-violaceous patches were observed on his ears (Fig. 1) and on the lateral walls of the abdomen (Fig. 2). Over the following days, the lesions became infiltrated edematous papules and plaques that subsequently progressed to ulcerated necrotic plaques with an erythematous halo.

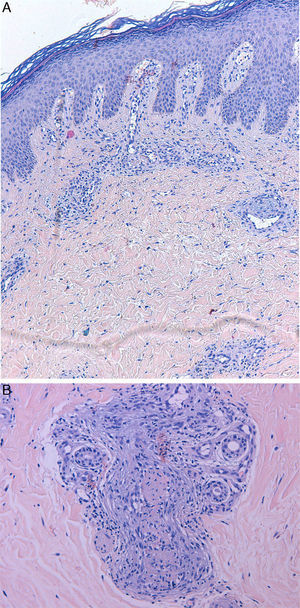

Full blood count and biochemistry were normal, including liver and kidney function tests. Urinalysis was unremarkable. Autoimmune screening revealed a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, positive anticardiolipin M (48U/ml), and positive antinuclear antibodies (titer, 1:160) with a speckled pattern. Complement was normal and the extractable nuclear antibodies panel (Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Ro, La, Scl-70, Jo-1), double-stranded DNA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and cryoglobulins were negative. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) were negative and coagulation studies were normal. Chest X-ray did not show any relevant features. A full-thickness skin biopsy showed a leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial and deep dermal and subcutaneous vascular plexuses, with some thrombotic features (Fig. 3). Urine drug screening was not performed. Based on these tests, we made a diagnosis of cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis secondary to the use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine. The patient was treated with topical copper sulfate 1:1000 and betamethasone dipropionate, 0.05%, for 2 weeks, with an excellent response and complete clearance of the lesions without scarring, and no new lesions developed. The patient did not attend follow-up appointments.

DiscussionSkin lesions are rare after cocaine use; they usually develop 1–4 days after exposure to the drug. The clinical spectrum can be broad and may be associated with digital vasospasm, Raynaud phenomenon, livedo reticularis, Buerger's disease, urticarial vasculitis, bullous diseases, acral ulcers, gangrene, and small and medium vessel vasculitis.1–4

Lesions usually have a rapid onset, with a painful violaceous rash that tends to ulcerate and become necrotic, typically affecting the face (ears and cheeks) and lower legs. Systemic complications are uncommon except for joint pain, which is common.1,3–9

The pathogenesis of the condition is largely unknown, although some research points to tissue ischemia caused by blood vessel constriction, direct or indirect blood vessel damage induced by immune complexes, or thrombosis.1–3

Histopathologic features can include vascular thrombosis and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, with or without fibrinoid necrosis. These are nonspecific features and can be found in many other disorders.1,3,5

Patients may develop antiphospholipid antibodies (namely IgM anticardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant) and ANCA with a cytoplasmic (c-ANCA) or perinuclear (p-ANCA) pattern. C-ANCA antibodies almost exclusively target proteinase 3 (PR3) antigen whereas p-ANCA antibodies can bind multiple antigens, including myeloperoxidase, lactoferrin, human neutrophil elastase (HNE), and PR3; HNE is specifically targeted after cocaine use,1,3,4,10 and this may induce neutropenia in some patients,1,9 which can lead to confusion with other vasculitides, particularly with the ANCA-positive vasculitides (polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis). As no pathognomonic laboratory or histopathologic criteria exist, the diagnosis is purely clinic and is made by exclusion. A detailed clinical history and a high level of clinical suspicion are paramount.1,3–9

The diagnostic approach to cases of suspected cocaine-induced cutaneous vasculitis should include complete blood count, biochemistry including liver and kidney function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinalysis, chest X-ray, fecal occult blood, full thickness skin biopsy, antiphospholipid antibodies, coagulation studies including homocysteine and proteins C and S, cryoglobulins, serum ANCA and ANA antibodies, double-stranded DNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor and complement levels, and serology for HIV, HBV, and HCV. Other tests such as blood, urine, or skin microbiology should be performed as required.1,3,4

The skin lesions usually resolve within 2–3 weeks after cessation of cocaine use. Normalization of laboratory tests can take 2–14 months, though the neutropenia recovers fully in less than 10 days.1,3,5,7,8

There is no consensus regarding treatment of this condition. Obviously, removal of the cause is the most important measure, together with symptom relief. Good clinical outcomes have been reported with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for arthralgia and colchicine, dapsone, oral antihistamines, and pentoxifylline for the skin lesions.1,3,4 Systemic corticosteroids have not been shown to be effective.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.