Cosmetic dermatology deals with the beauty and appearance of the skin–a most important element of body image. Treatments used in cosmetic dermatology (hygiene, hydration, protection, repair) aim to enhance the characteristics of the skin, its anatomy, its function, and its vitality, to produce aesthetic improvements. Communication with the patient is essential in medical consultations and we believe that it has special connotations in cosmetic dermatology that must be taken into account. In this article, we present a 3-pillar model for communication with cosmetic dermatology patients that rests on 3 skills: assertiveness, empathy, and critical judgement.

La Dermatología Estética se ocupa de la belleza y apariencia de la piel, una parte importantísima de la imagen corporal. Los tratamientos utilizados en Dermatología Estética (higiene, hidratación, protección, reparación) buscan potenciar las características propias de la piel, en su anatomía, función y vitalidad, y esto se traduce en mejoras del aspecto estético. La comunicación con el paciente es fundamental en la consulta médica y entendemos que la Dermatología Estética tiene connotaciones especiales que deben considerarse. En este artículo se presenta un modelo propio de tres pilares en la comunicación con el paciente estético y se exponen tres habilidades humanas como dichos pilares: asertividad, empatía y juicio crítico.

Our job is to care for our patients, irrespective of what they may ask us to do. We care for people and we work directly with the public as both receivers and transmitters of information. Consequently, we need to have a good understanding of the basic characteristics and component elements of communication (based on an understandable code in an appropriate channel without interference or noise if possible) and also be aware of the different types of communication we use (verbal, gestural, and paraverbal).1–5 Mastery of all these parameters is a basic requirement in our profession.

In this case, we are not talking about communication between two people on the same level. Our training in this field must ensure that we have a high level of skill. When receiving information we must listen actively and when we are communicating information we must ensure that what we say is relevant, complete, verified, couched in terms the patient can understand, and honest. Honesty is always important in medical care, but in cosmetic medicine everything must be made particularly clear. We must also be sincere, even persuasive sometimes, as well as emotive and proactive, so that the patient will get involved in their own care and treatment; and, obviously, we must talk common sense.2

But physician-patient communication is much more than just giving and receiving information: starting from the great medical training we receive in our specialty, communication is more than just being polite to our patients.4 Owing to its complexity, clinical communication is an academic discipline in its own right.3 This has a lot to do with the fact that it requires very advanced emotional management skills; we have to reflect on actions and manage feelings and expectations (this last so very important in cosmetic medicine).6 Because of the complexity and importance of physician-patient communication, this topic is not only dealt with in articles in medical journals, it has also been the subject of veritable treatises.1–4 In fact, clinical communication is an increasingly on-trend topic and we find references to it in very diverse media, including newspapers7 and even on the website of our own association.8 The reason for this interest is that our work actually depends, in great part, on our communication skills. Our diagnostic success depends fundamentally on whether or not we obtain a good clinical history (more effective than any test).3 Our patients’ commitment to their treatment also depends on how well we communicate with them, and it has even been reported that mutual trust between the physician and the patient enhances the therapeutic value of care.9 Finally, we must communicate effectively with our patients if we are to enjoy what we do.1 Poor communication will lead to growing personal dissatisfaction for both parties, and little by little we will stop liking our work and even our profession. Moreover, several studies, those of Backman10 and Levinson11 for example, have shown that the majority of medical malpractice claims are the result of poor physician-patient communication.10,11 This association may be even more marked in cosmetic medicine given the absence of a diseased state susceptible to obvious improvement or an outcome that can be clearly demonstrated and proven by test results. In our field, we depend on the subjective personal satisfaction of a person who sees an improvement in the appearance of their skin, independent of more or less objective evidence. It is important to remember that in cosmetic medicine we are not dealing with a patient who requires a cure (not the primary need); rather, our patients come to us with a desire or a hope, even though some of them may view their desire as a necessity and some may even present their wishes to us as a necessity. Moreover, our patients come to us voluntarily and we can also choose whether or not we will treat them.

Despite everything that has been said about communication in healthcare and the large number of articles that have been written on the topic, we have not found any publications in the literature referring specifically to physician-patient communication in cosmetic dermatology.

ObjectiveOur objective in this article was to try to identify some protocols, skills,and strategies that favor communication in cosmetic dermatology.

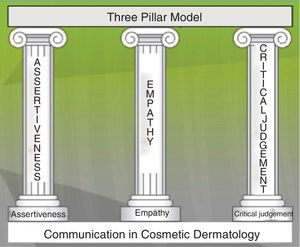

Material, Method and ResultsTo achieve our objective, we focused on 3 closely related human skills that determine how we listen to and communicate with the cosmetic dermatology patient. Figure 1 shows the resulting 3-pillar model (Fig. 1). The 3 pillars are as follows:

- -

Assertiveness: the ability to express oneself clearly and directly, saying what we want to say without offending or disparaging the other person and being aware of and defending our own rights while respecting others.6

- -

Empathy: the human ability to understand and share the feelings of other people, without necessarily thinking in the same way as that person.6,12

- -

Critical judgement: the ability to think critically, leading us to verify, analyze, understand, and evaluate what we observe in the patient—observations that inform our initial and differential diagnoses (in cosmetic dermatology taking into account the possibility of body dysmorphic disorder and other such conditions)—and to analyze and check our treatment decision, as we would in any other branch of our specialty.13,14

With respect to assertiveness, our reason for choosing to work in cosmetic dermatology should be because we like the field and we want to help our patients, because nobody is obliging us to choose this specialty. We must have a clear idea of what we want to do within the subspecialty and what we want to achieve with our treatments. And we also need to be clear about what we do not want to do. Moreover, we have be able to defend and explain our position, while respecting our patients and their feelings. In this context, it is important that we know how to use the following techniques when talking to patients.

We should know how to use “I” messages, that is, statements in which the speaker expresses what he or she feels and would like without belittling the other person: “I think that ...”, “I have not found that technique to be useful”, “I don’t share your opinion in that respect”.

Avoid value judgments—very important in cosmetic dermatology. Avoid comments like the following: “You should not worry so much about your appearance”, “You are worrying about a problem that does not exist”, “That is not important”.

Know how to say no. If at any time you are uncomfortable with something a patient asks you to do or feel that you should not treat the patient based on your critical judgment, say no in an assertive way.

Taking care of and protecting our appearance is a praiseworthy and useful quality that helps us adapt to change, get on with other people, and cope with difficult situations.15 As well as being part of our identity, our physical appearance and its expressions are, from a very young age, an important component of our emotional world and our ability to connect with other people.16 The results of studies carried out using the DEBIE questionnaire have shown that there is a relationship between cosmetic dermatology and emotional well-being.15,16 The findings of those studies also indicate that it is people who are more assertive and report greater baseline well-being who value these treatments and the benefits they can offer in their daily lives. And this finding illustrates what we are really looking for: patients who want to improve themselves and take care of themselves because they are well and not because they are unhappy. We must use our critical judgment to detect unrealistic expectations and make a differential diagnosis. It is important to make it clear to the patient that the aim of a treatment is never to halt the aging process but rather to help them age more healthily and in consonance with their mental vitality. As dermatologists, our objective is to take care of the skin and keep it functionally younger, healthier, and more harmonious and that will result in aesthetic improvements.15,16

Critical thinking is a cognitive skill and natural ability that we use in all our consultations as physicians. We analyze, evaluate, and synthesize all the information we glean from a consultation. Critical thinking and judgement involves careful observation, applying the scientific method, drawing on experience, and using our reasoning faculties.13 And in the case of cosmetic dermatology it also draws on our creative, imaginative, and artistic reasoning. Critical judgement comprises 2 main components:

- -

Cognitive skills, that is, our knowledge—mainly medical—which we use to establish a diagnosis and differential diagnosis (very important in this setting) and to decide on the best treatment plan.

- -

A disposition to verify and to analyze all the factors from different standpoints (checking the information and our decision, evaluating the pros and cons). Although we have a duty to check on our knowledge, we have to keep our patients safe and communicate that safety to them.14

Empathy is the central pillar of our model, the key to complete and correct communication with the patient.6,12 There are different levels of empathy—natural, basic, advanced, and very advanced—and our profession demands a very advanced level.1 Empathy relates to our ability to understand our patient's feelings and to communicate that understanding to them, either verbally (for example, “I understand the concerns you have about your skin”) or nonverbally (for example, with an appropriate facial expression). Empathy requires us to reflect and to make a conscious effort to recognize the other as a person with emotions. It requires patience (some patients may irritate us but we have to control those feelings so that we can be open to everyone, whoever they are and whatever their needs). Finally, it requires courage because it can generate feelings and emotional reactions that we have to control.12 However, it is a source of great motivation and creativity. Empathy is an attitude attained through active listening, in this case to the cosmetic dermatology patient, without making assumptions and with the intent of helping the person (by listening carefully to what they say, treating them, or sometimes simply making a referral). Empathy enables us to manage the emotions that arise during the consultation using a variety of strategies, including confrontation, amplification, minimization, to mention just a few.6 And it also involves a number of functions: catharsis, change, exculpation.1 In the case of empathy—unlike sympathy—the clinician is not emotionally involved but is, at all times, aware of the patient's feelings, and of their own. Nor is empathy the same as cordiality, which is a habit and may be automatic, and does not involve any reflection or effort. Cordiality is what happens when we greet our patients when they arrive and when we show them out at the end of the consultation—the moment when we recognize the other as a person. However, a friendly and cordial atmosphere (“Welcome, please come in”) favors an empathic interaction.1–6,12

Nevertheless, there has to be a limit to everything, and we know that unlimited listening is neither possible nor opportune. Moreover, empathy must always be accompanied by assertiveness: we must know how to say no to certain requests and to set limits in order to avoid contraindications or iatrogenesis due to excessive empathy. For example, in the case of an aggressive or demanding patient, it is important to guard against excessive empathy that the patient might interpret as insecurity or a lack of assertiveness on your part. Similarly, a manipulative patient looking for someone to blame may interpret empathy as agreement. Such a situation has to be managed carefully and requires exculpatory empathy that affirms the physician's good intentions, because a clinician who is embarrassed cannot be empathic.1

An essential skill in our subspecialty (even more so now that patients are influenced by the ubiquitous coverage of these issues in advertising and the media) is to be able to use our critical judgment to identify patients with unrealistically high expectations of what can be achieved. With assertiveness and empathy, we must strive to reduce these expectations and bring them into line with reality. If this proves impossible and the patient continues to have unrealistic expectations, we can, once again with empathy and assertiveness, refuse to treat them. This is very important if we are to avoid unnecessary frustrations.11

In cosmetic medicine, as in any other medical specialty, our practice is guided by normal medical ethics: striving for moral excellence, ensuring patient privacy (very important in cosmetic medicine), obtaining informed consent, and sharing decision making with our patients.17 All our team members must follow the same line, being friendly, kind, and empathic.

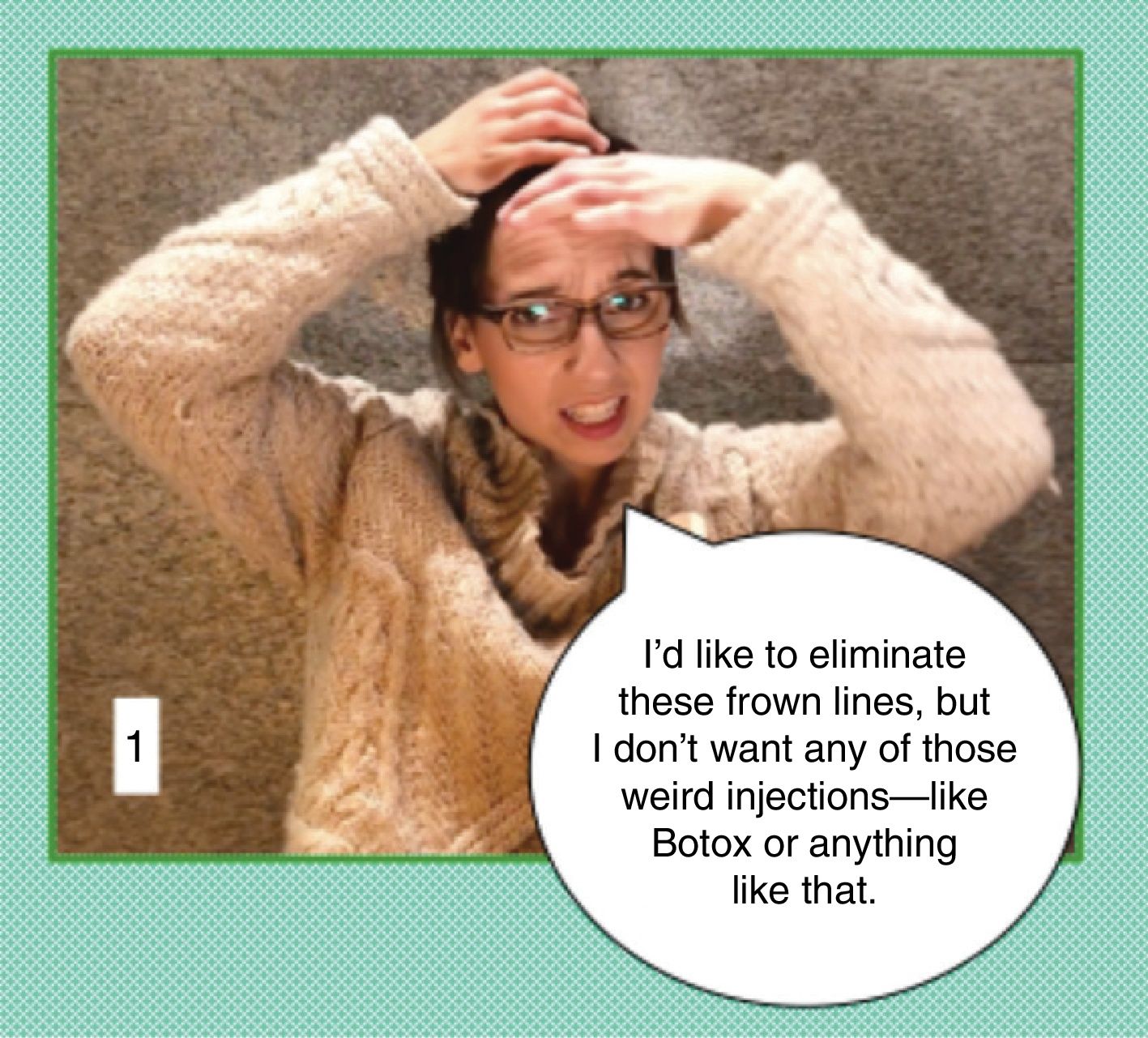

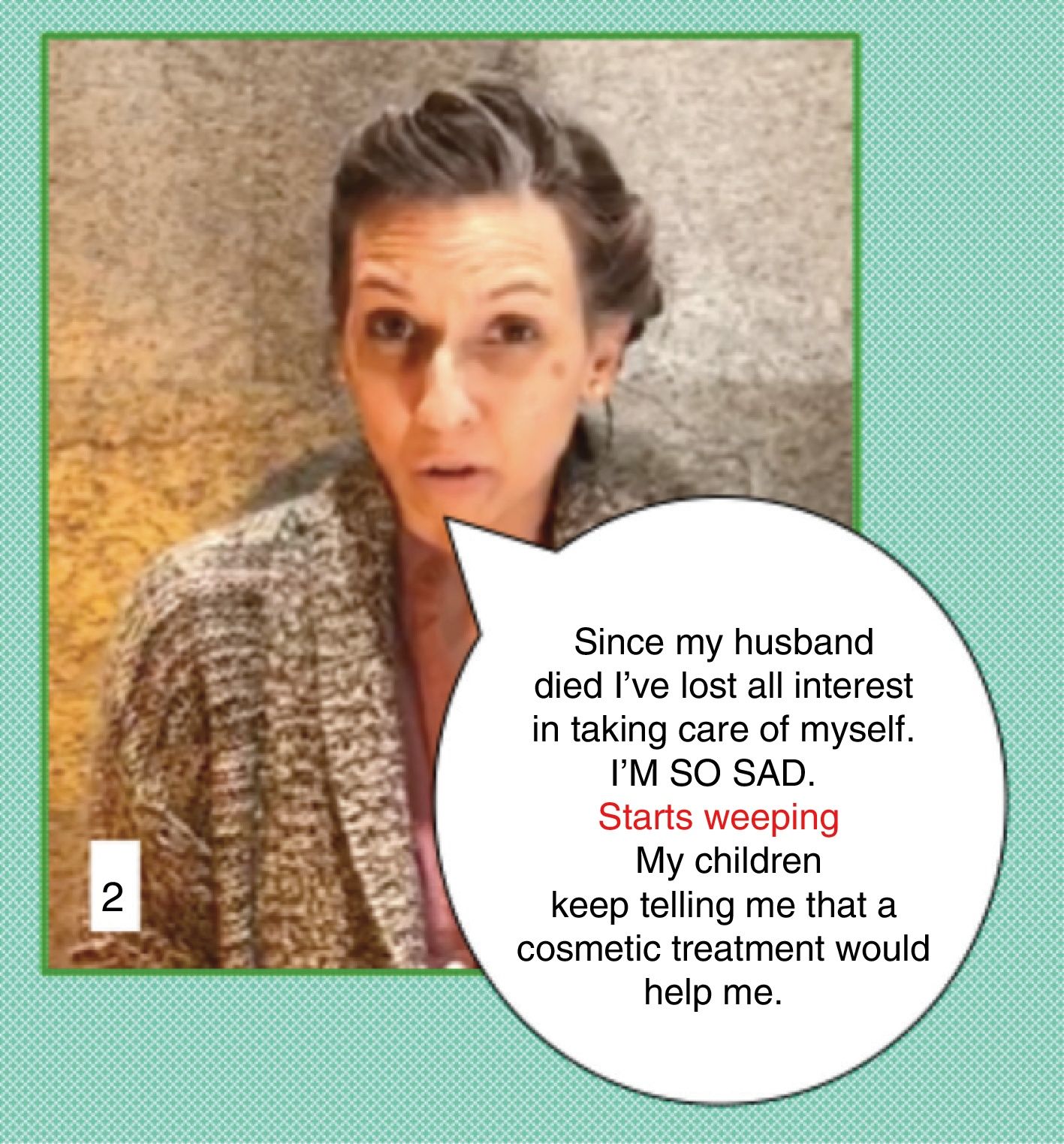

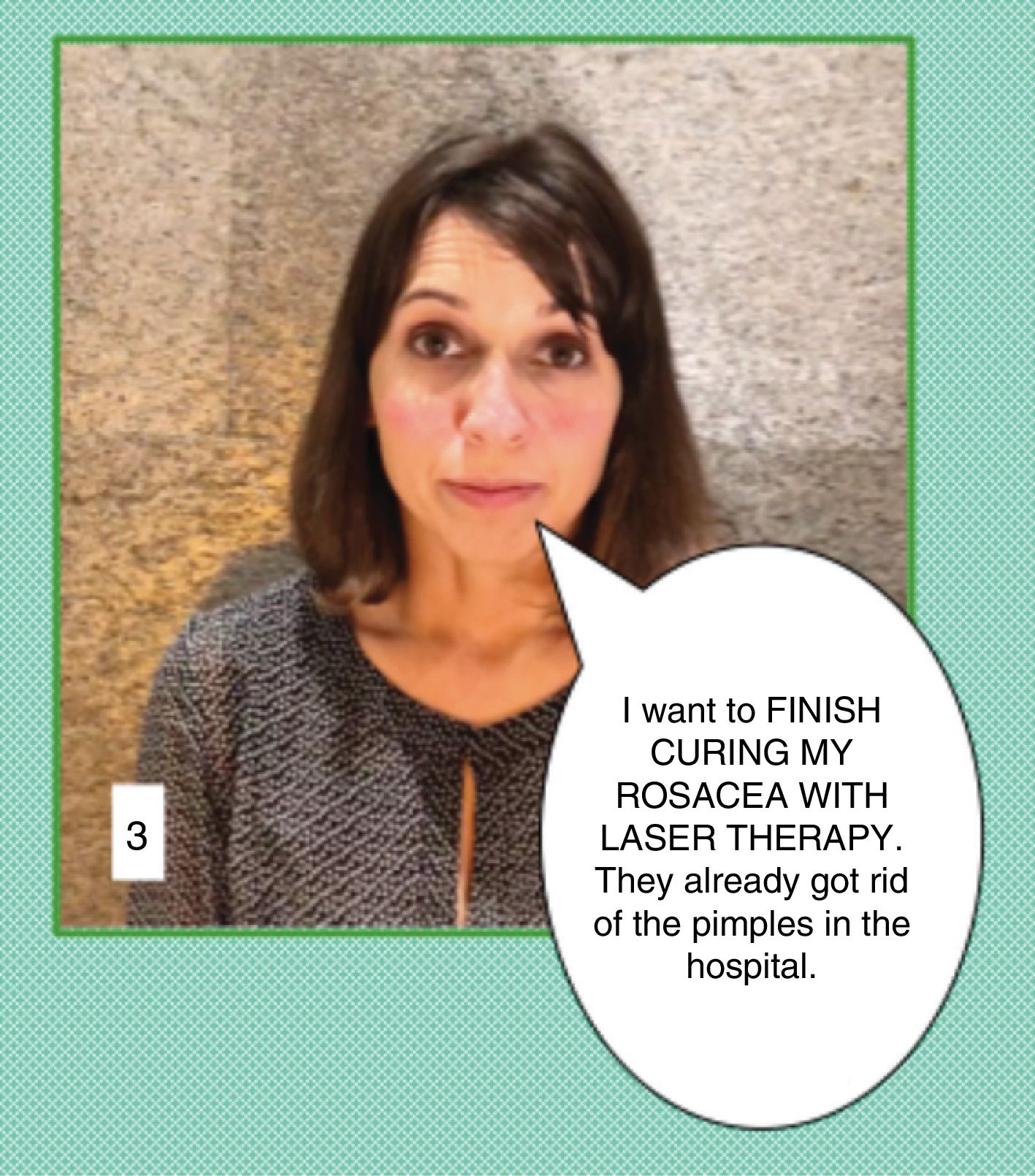

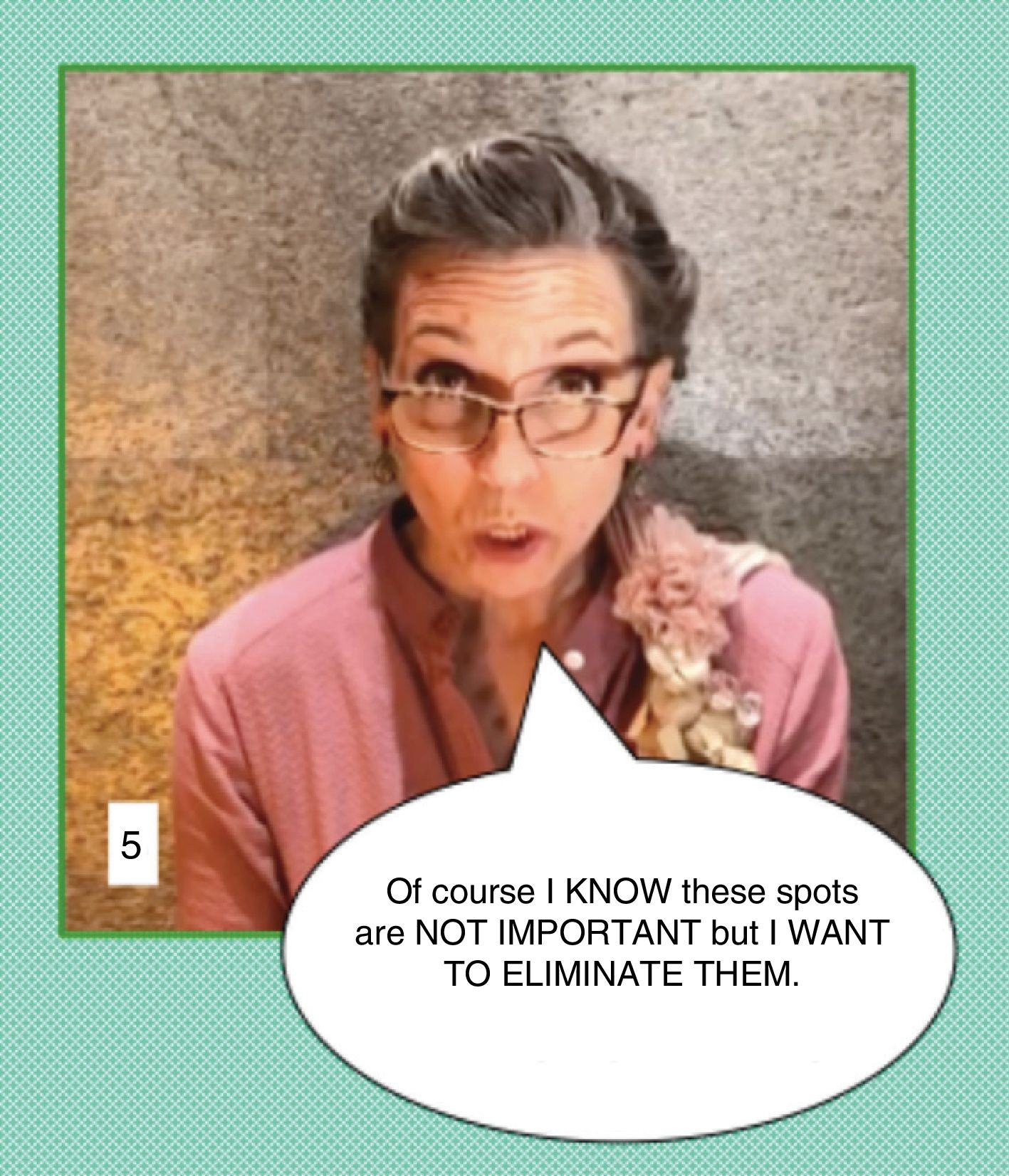

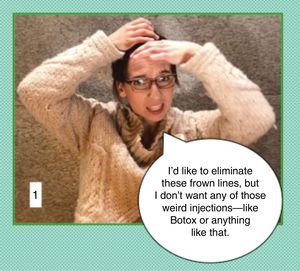

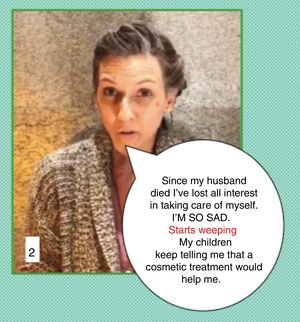

With an eminently practical intent, in Figs. 2-7 we present 6 clinical cases illustrated with images professionally characterized by Marta Mardó (Higher Degree in Dramatic Arts, Master in Interpretation). These figures represent 6 different patients attending our consultation who explain what they want, each with their own personality and personal circumstances. We could analyze the possible dialogue for each case in detail, taking into account the variables mentioned above: assertiveness, empathy, and critical judgment. However, for reasons of space, we have limited ourselves to commenting in the figure legend on a few simple alternatives for each case.

Communication in cosmetic practice: Clinical case 1. This person wants to eliminate her frown lines, but without any of "those weird injections”. The physician must be patient; sometimes patients seem to be looking for magic. In this case, the patient is an educated and well informed person, who is afraid. Following a complete physical examination, the physician will have to explain what botulinum toxin is, the proven safety record and limited durability of the treatment, and the desire to seek natural-looking results. We have to change the patient's perception so that the person who comes into the consultation expressing doubts and fear leaves in a more calm frame of mind. And she will request an appointment for treatment when she makes her decision.

Communication in cosmetic dermatology: Clinical case 2. In this case, we can help the patient a great deal by doing very little. For example, simply by offering her a tissue when she dissolves into tears, we can facilitate catharsis. The gesture shows your respect and indicates that you support and empathize with the speaker. This gives the patient permission to express her emotion in all its intensity and in that catharsis she will probably realize that there is no point in undergoing a cosmetic procedure or treatment at this time. However, you can offer her a clinical assessment and recommend home cosmeceutical therapies. Later, when she is feeling better, both in her mental state and her skin due to the home treatment, you can suggest treatments designed to reduce the overall photoaging of her skin. In this way, you can establish an affective connection, using an empathic attitude to ensure that the patient does not lose her trust in you as a person and, at the same time, continues to see you as a health agent interested in enhancing her wellbeing. Sometimes postponing treatment is the best way to proceed, so that treatment can be started later with greater confidence in the results and in the acquisition of a routine. At the same time, the decision can reaffirm us as doctors. The patient will definitely leave the consultation feeling much better because she has been listened to, cared for, and understood. And she will leave with hope and with the enthusiasm and motivation to return in the future.

Communication in cosmetic dermatology: Clinical case 3. This case presents several challenges: the patient is asking for a cure for a chronic disease and, what is more, it appears that this is what she has understood from what she was told when receiving treatment in a hospital. We must clarify the real situation, patiently explaining what rosacea is and what laser therapy can achieve and further add that any treatment will require maintenance. In effect, we have to bring her expectations into line with reality.

Communication in cosmetic dermatology: Clinical case 4. In this case, the physician may be surprised for a number of reasons. The patient is talking about a defect we do not perceive. It is possible that the patient has body dysmorphic disorder. Furthermore, she may be lying when she says that the previous lip augmentation procedure with hyaluronic filler was done “ages ago”. Looking at her lips, we can see that the procedure was more likely performed recently or perhaps it was not done with hyaluronic filler but rather with some other material that would contraindicate hyaluronic therapy. The patient also complains about the results of earlier treatment. In this situation, without hurting her feelings, the best course of action would be to tell the patient that you are unable to offer her that treatment because, medically, you do not consider it to be indicated at this time. In this exchange it is unnecessary to either contradict or agree with the patient.

Communication in cosmetic dermatology: Clinical case 5. This patient has a demanding attitude and she wants to eliminate spots. While the word eliminate probably bothers us, we think we might be able to help her. Furthermore, she already believes that none of the lesions she has are of any concern. In these circumstances, it is important to maintain a scientific and medical attitude: “I see…Please come in. The first step is to carry out a physical examination so that I can assess what kind of spots we are talking about”. After performing the examination and any necessary tests—and if the only findings are lentigines and ephelides—we can explain the situation to the patient. It is important to adjust the patient's expectations, explaining that we can help her to improve her spots, and discuss the techniques we consider could be useful. Once we have given this explanation and recommended measures she can implement herself at home, we can leave it up to the patient to decide whether she wants to undergo further treatment. In this case, with empathy and assertiveness, our aim is to change the patient's attitude. The patient accepts our empathic behavior and, at the same time, is surprised by our scientific and safe approach. It is probable that she will change her behavior from imposing her will to asking for and accepting our advice.

Communication in cosmetic dermatology: Clinical case 6. Finally, the sixth patient is someone who wants to improve the quality of her skin and her approach is similar to our own. She is already a patient and she trusts our work because we have treated her cancer. Her self-esteem is high and her attitude is assertive. Normally, with a patient like this, the relationship will be fine and the treatment will go smoothly. This kind of patient is common in dermatology.

Our message can be summarized as follows:

- -

Assertiveness, empathy and critical judgment are essential skills in our communication with the cosmetic patient and for properly managing their expectations.

- -

We must enjoy our work and understand our patients and their hopes and wishes.

- -

Our medical and professional ethics must inform everything we do.

- -

It is important that the patient be in a good emotional state before treatment.

- -

We must do a lot of expectations management.

- -

We can say no when we do not consider it appropriate to treat a patient.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Marta Mardó (Higher Degree in Dramatic Arts - Master in Interpretation) for her work characterizing the clinical cases.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-González MC, Martínez-González RA, Guerra-Tapia A. Dermatología Estética: habilidades humanas claves en comunicación. Modelo de los tres pilares. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2019;110:794–799.