This consensus document analyzed the management and emotional journey of patients with GPP (generalized pustular psoriasis), and the desirable course of the disease while detecting critical points and translating them into needs and recommendations. This project was conducted in 3 phases with participation from an advisory committee (n=8), an expert panel (n=15) and patients with GPP (n=6). The patients’ disease progression was heterogeneous due to disease variations, different health care models implemented and available resources, and the lack of diagnostic and treatment guidelines. A total of 45 different recommendations have been made to optimize management and address the emotional component of these patients. Five of them stand out for their impact and viability. Therefore, a roadmap of priorities has been made generally available to improve the management of patients with GPP.

Este documento de consenso analiza el recorrido asistencial y emocional de los pacientes con psoriasis pustulosa generalizada (PPG), así como el recorrido deseable, detectando puntos críticos y traduciéndolos en necesidades y recomendaciones. A través de un enfoque multidisciplinar que involucró a un Comité Asesor (n=8), panel de expertos (n=15) y pacientes con PPG (n=6), se llevó a cabo este proyecto en 3fases. El recorrido de atención de estos pacientes resultó heterogéneo debido a variaciones en la enfermedad, modelos de atención y recursos disponibles, así como la carencia de guías de diagnóstico y tratamiento. Se han consensuado 45 recomendaciones para optimizar la atención y abordar el componente emocional de estos pacientes. Cinco de ellas se han destacado por su impacto y viabilidad. Así, se pone a disposición general una hoja de ruta de prioridades para mejorar el recorrido asistencial de los pacientes con PPG.

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, chronic, potentially life-threatening skin disease characterized by widespread outbreaks of sterile neutrophilic pustules, which may be accompanied by fever and systemic inflammation.1 GPP has a significant physical, emotional, and social impact on the patients’ quality of life, even during latent periods. In Spain, the prevalence of GPP in adults is 13.05 cases per million inhabitants.2 A retrospective study conducted in Spain estimates the rate of outbreaks at 0.55 per patient/year, noting that 41.1% of patients were hospitalized, at least, once.3 Although GPP can preset at any age, it typically begins around the age of 50, except for patients with IL-36RN genetic mutations, in whom it tends to start earlier.4,5 It affects men and women equally, although there is a slight female prevalence, and certain forms that appear during pregnancy pose a significant risk to the fetus.6–9

Currently, the management and therapeutic approach to GPP is individualized due to the lack of national or European guidelines and approved treatments for controlling GPP outbreaks. Recently, a drug for GPP (spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor) has been approved in Europe.4,10–14

In this context, this consensus was initiated to analyze the current care and emotional journey of GPP patients and conduct an analysis that would identify areas with room for improvement and make recommendations to enhance patient care.

MethodologyWe put together an Advisory Committee of 8 people, including health care workers (3 dermatologists, 1 psychologist, and 2 representatives from the health administration) and 2 representatives from patient associations on dermatological and rare diseases. To provide an actual clinical practice perspective with a multidisciplinary view, an additional panel of 15 experts from various fields (Dermatology, Internal Medicine, Rheumatology, Primary Care, Psychology, Nursing, and Pharmacy) including health care managers and economists, was created. Additionally, the perspectives of a group of 6 GPP patients were added to the mix.

To analyze the current approach to GPP, we conducted a narrative literature review on PubMed and gray literature, using “generalized pustular psoriasis” and “GPP” as search terms. The Advisory Committee selected relevant articles. To collect qualitative information on the management of GPP based on the routine clinical practice, individual interviews were conducted with the Advisory Committee and the expert and patient groups using a general semi-structured questionnaire adapted to delve into specific aspects with the different panel profiles. The analysis of the entire care circuit and emotional journey was structured into 4 phases: disease onset, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Finally, we conducted a qualitative synthesis of the collected data.

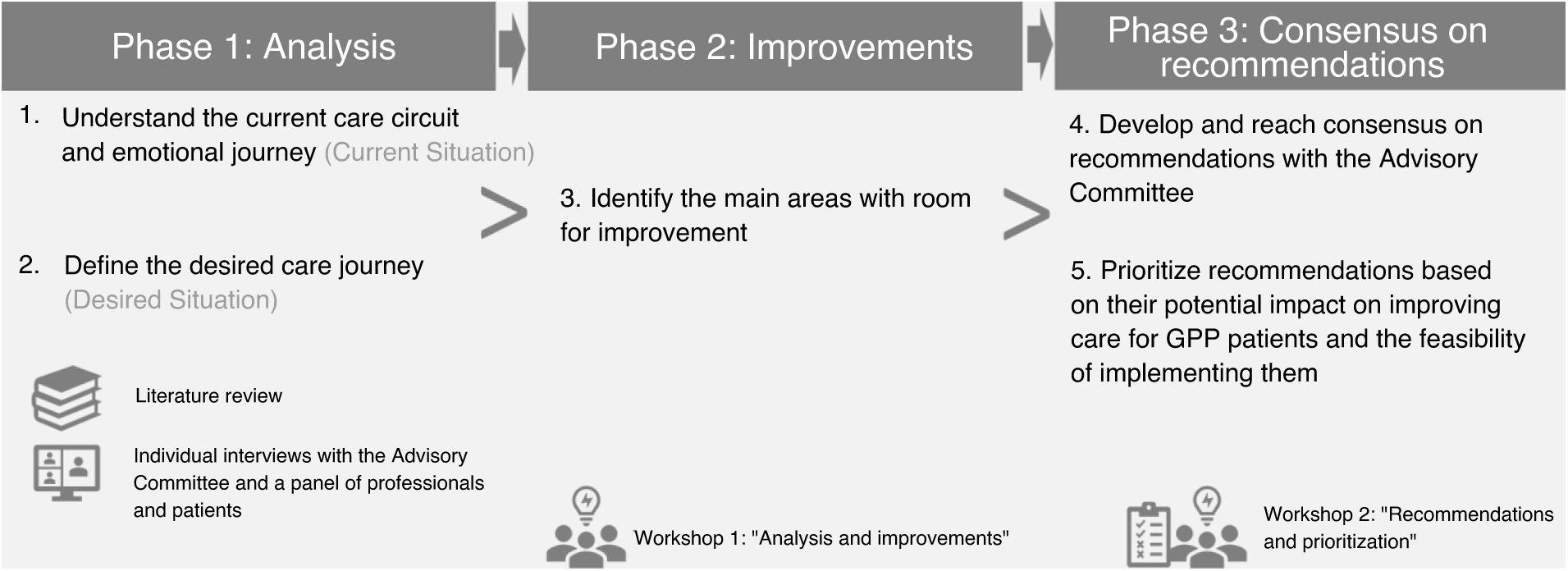

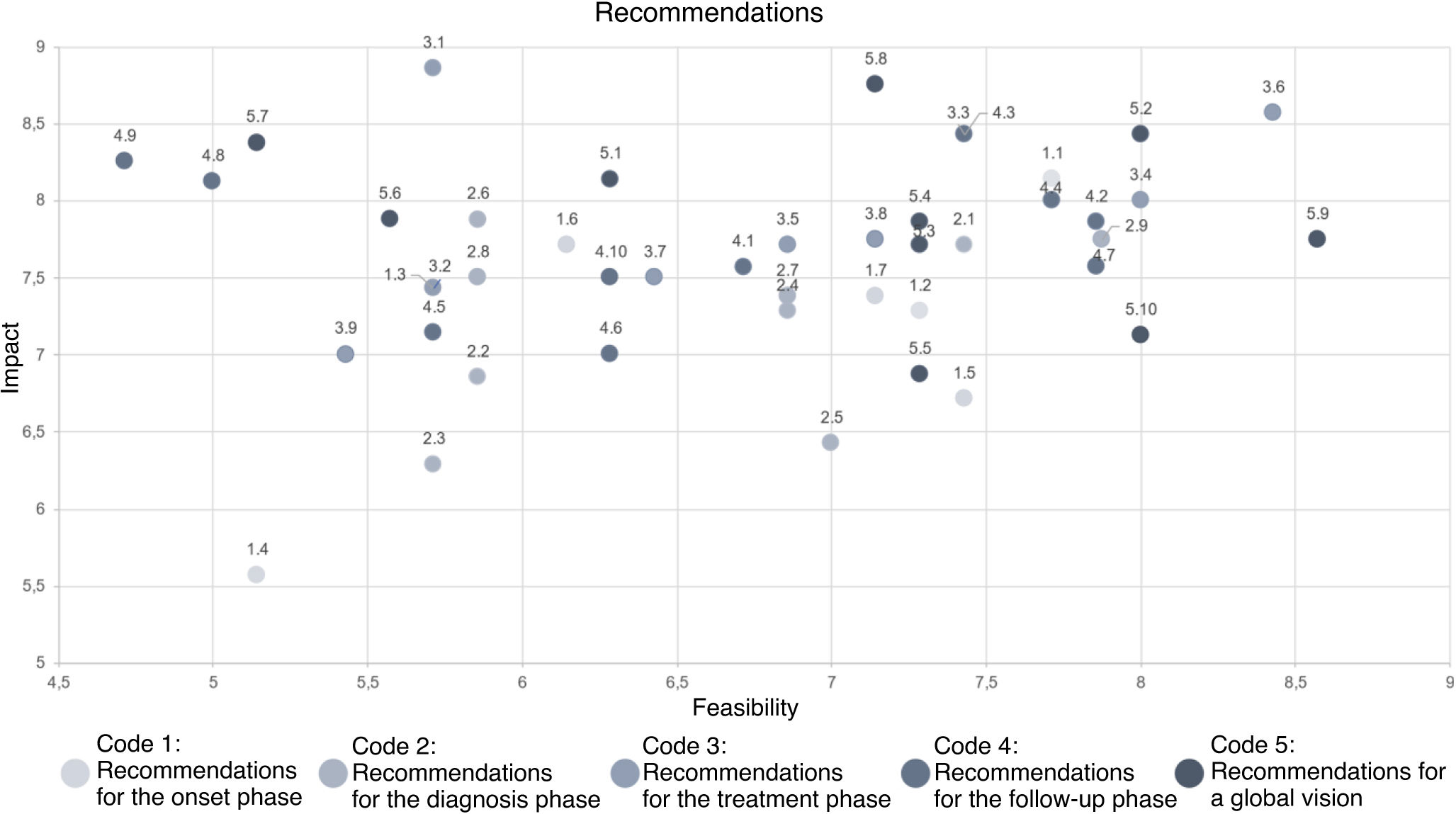

In a first meeting, the Advisory Committee analyzed the qualitative synthesis of the entire health care circuit and patients’ emotional journey and identified key unmet needs and areas with room improvement. In a second meeting, recommendations to improve GPP patient care were agreed upon. Individually, the Advisory Committee prioritized the agreed recommendations by rating the impact and feasibility on a scale from 1 to 10. Impact was rated as the ability to improve patient care, and feasibility as the ease of implementing the action based on required resources and associated organizational complexity. The project development phases are illustrated in Figure 1.

ResultsFor each phase of the GPP patient care circuit and approach, the emotional situation, and priority improvement recommendations were described.

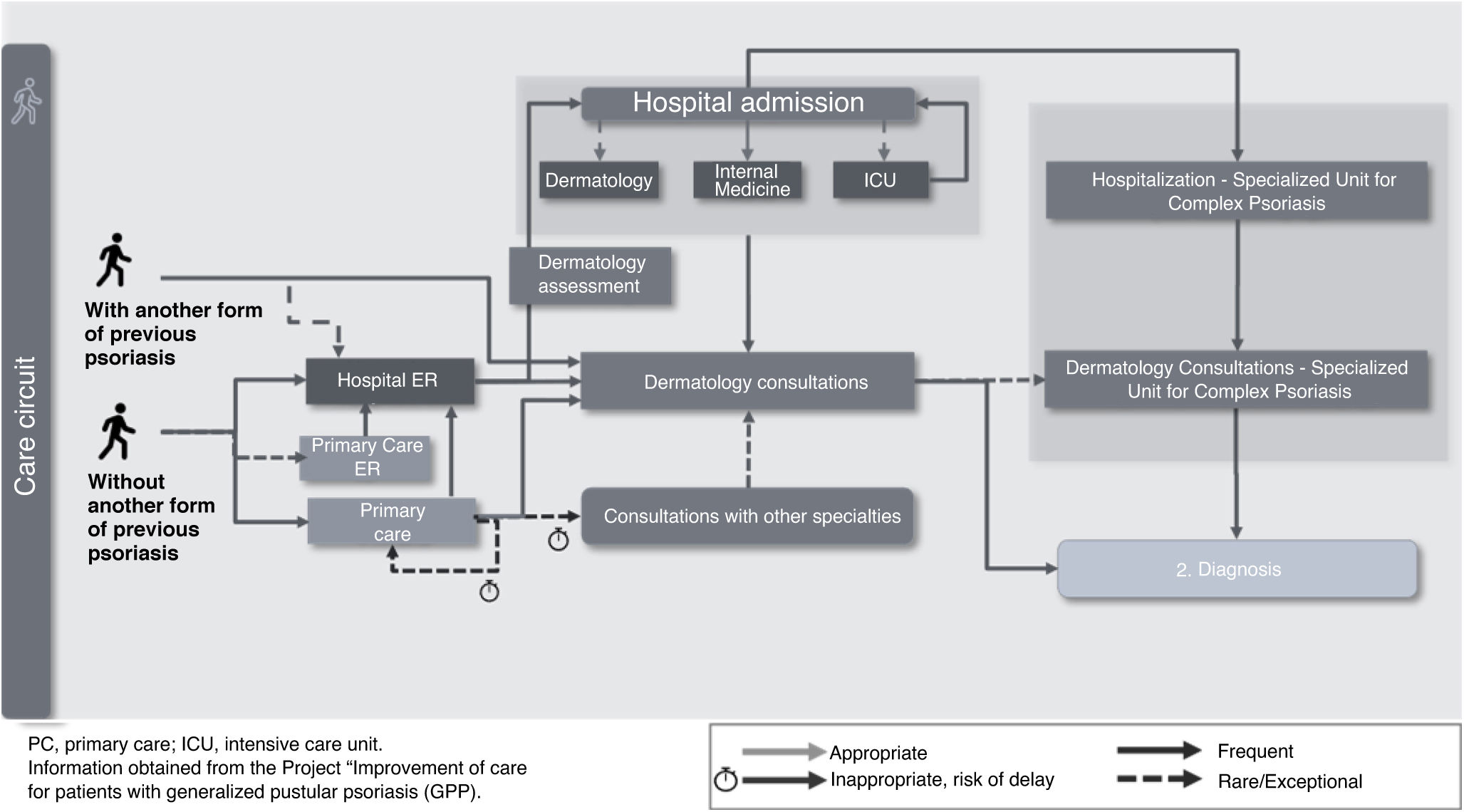

Disease onsetEntry into the health care system is mainly influenced by a history of dermatological disease (patients with or without previous forms of psoriasis) and the intensity of disease onset (abrupt or subacute onset). The main delays in referral to Dermatology occur in forms with subacute onset with no previous dermatological disease, whose symptoms are more easily confused with other dermatoses. Patients with a more abrupt and extensive disease onset often tend to access the system through the ER or rapidly access Dermatology units due to their skin lesions (Fig. 2). Emotionally, uncertainty abounds due to a lack of information and knowledge about the disease.

Among the priority recommendations for this phase, improving knowledge about the disease, especially in Primary Care and the ER, and implementing systems and tools for checking the patients’ medical history to facilitate referrals to Dermatology for specific warning symptoms were highlighted.

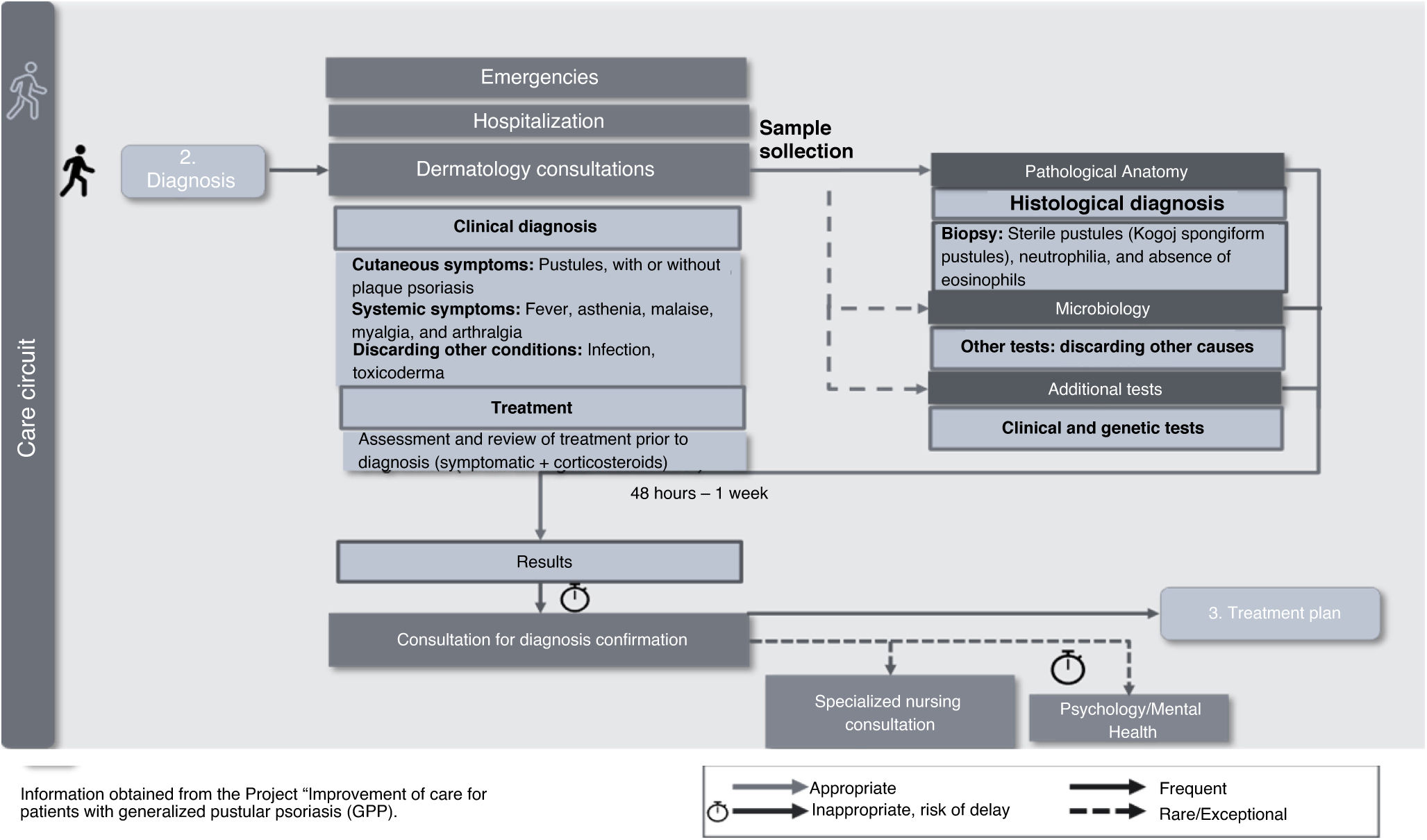

Diagnosis of GPPOnce the patient is in the Dermatology unit, and GPP has been suspected, a confirmatory clinical and histological diagnosis of GPP should be established. Diagnosis can be achieved when the patient is hospitalized with an outbreak or in a Dermatology consultation. There are no pathognomonic signs or specific clinical, histological, or serological data for GPP, which, along with the lack of standardized diagnostic guidelines, contributes to making the entire process difficult (Fig. 3). Emotionally, the lack of time to clarify doubts and receive information, and the delay and difficulty in accessing psychological support, negatively impact the patient.

In this phase, priority recommendations include: 1) the need to develop diagnostic guidelines including comprehensive dermatological assessment, genetic studies, and analytical tests; 2) facilitating access to priority diagnostic tests for these patients to reduce the time to diagnosis, and 3) adapting consultation times, creating informative individualized materials for these patients, and developing communication skills to overcome existing difficulties in conveying information to patients.

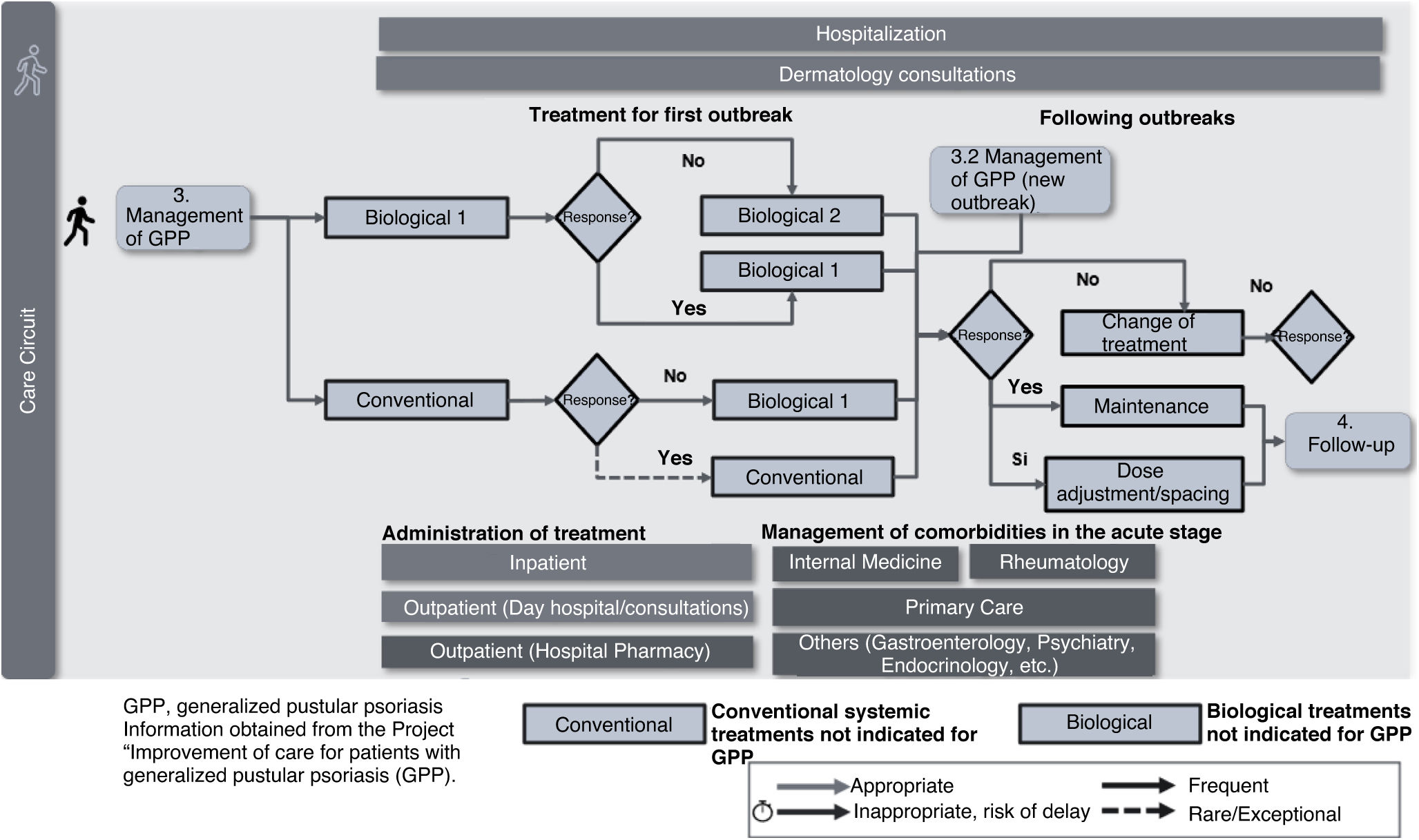

Management of GPPDepending on the previous medication administered and the initial assessment, the patient may start with conventional treatment or directly with a biological drug (Fig. 4). Currently, due to the lack of specific treatments for GPP in Spain, low evidence off-label drugs are used. This low evidence on the use of these drug for GPP often requires treatment changes due to lack or loss of response, with the corresponding negative emotional impact on the patient, exacerbated in some cases by difficulty accessing psychological support, fear of a new outbreak, and social or family misunderstanding. In complex cases with poor response, referral and coordination with specialist teams in high-complexity centers would be desirable.

Priority actions proposed in this phase include: 1) developing a registry of GPP patients to generate studies and evidence in clinical practice, and 2) the need to create treatment recommendations for patients in special situations to ensure quick access to treatment.

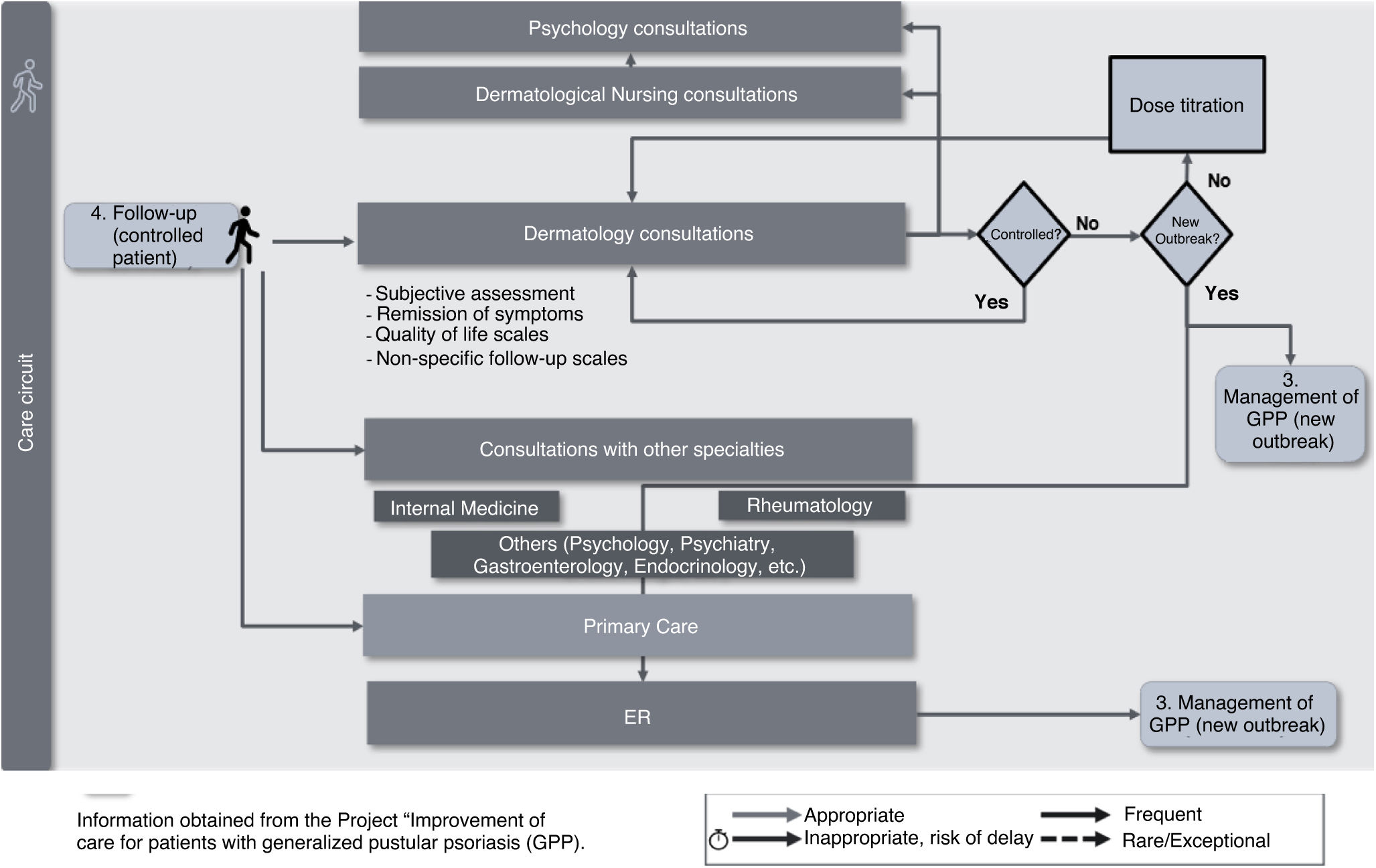

Follow-upWhen the patient's condition is under control with the treatment they are receiving, the dermatologist often schedules regular follow-up consultations to monitor the disease (Fig. 5). However, the lack of consensus on criteria for defining controlled/uncontrolled patients and the application of specific scales and quality of life assessments complicates performing optimal follow-up to prevent new outbreaks and restore a good quality of life. Emotionally, the greatest impact in this phase is associated with the patients’ fear of experiencing a new outbreak, which often affects their life planning (resuming studies, returning to work, professional development, sexual life, social relationships, and leisure activities, among others). Patients often report difficulties in returning to their previous life and the support needed to maintain a good quality of life that may be compatible with their disease.

Priority recommendations include: 1) the need to achieve consensus on the therapeutic objectives for GPP and the application of clinical and quality of life assessment scales, and 2) the need for systems to grant patients quick access to Dermatology in case of a new outbreak or adverse effects.

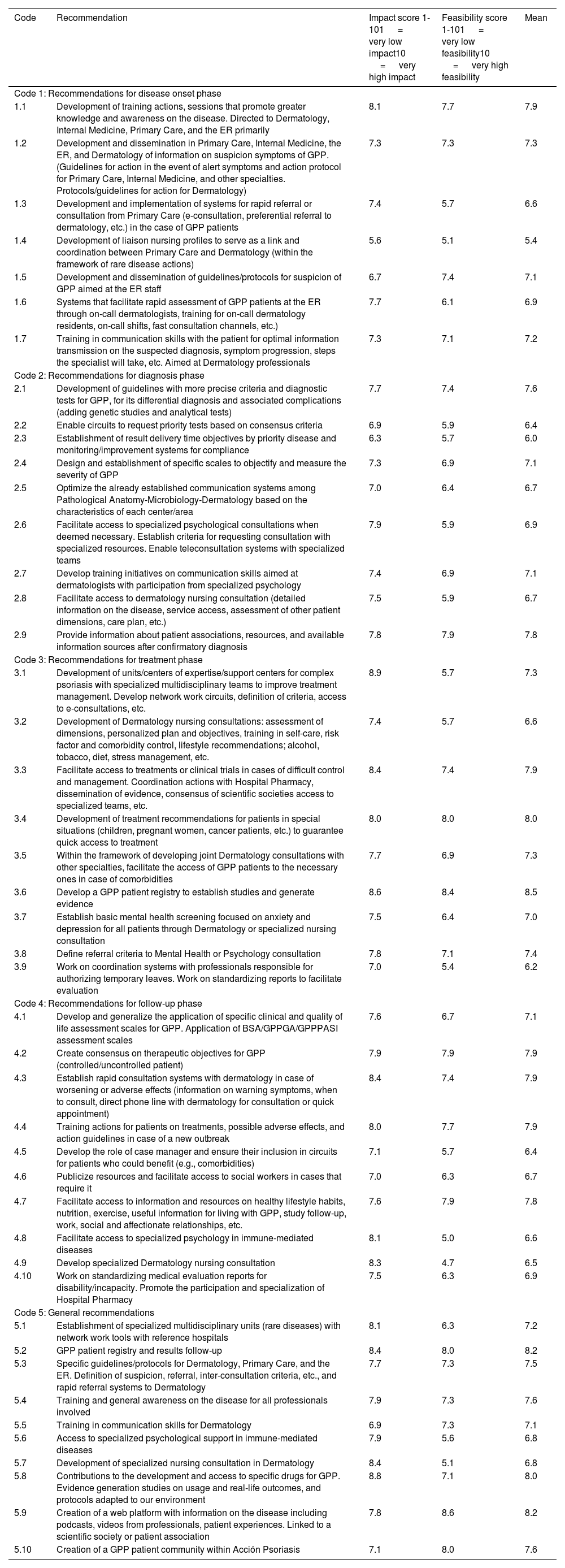

Overall, a total of 45 improvement recommendations were agreed upon. Table 1 shows the recommendations identified for each phase of the care circuit and their scores in terms of impact and feasibility, highlighting the top 5 actions with the highest scores. Figure 6 shows the results of the prioritization exercise displayed in a matrix based on the scored variables, impact, and feasibility.

Recommendations to improve the health care circuit of patients with GPP by phase, prioritized by mean score in impact and feasibility.

| Code | Recommendation | Impact score 1-101 = very low impact10 = very high impact | Feasibility score 1-101 = very low feasibility10 = very high feasibility | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code 1: Recommendations for disease onset phase | ||||

| 1.1 | Development of training actions, sessions that promote greater knowledge and awareness on the disease. Directed to Dermatology, Internal Medicine, Primary Care, and the ER primarily | 8.1 | 7.7 | 7.9 |

| 1.2 | Development and dissemination in Primary Care, Internal Medicine, the ER, and Dermatology of information on suspicion symptoms of GPP. (Guidelines for action in the event of alert symptoms and action protocol for Primary Care, Internal Medicine, and other specialties. Protocols/guidelines for action for Dermatology) | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 |

| 1.3 | Development and implementation of systems for rapid referral or consultation from Primary Care (e-consultation, preferential referral to dermatology, etc.) in the case of GPP patients | 7.4 | 5.7 | 6.6 |

| 1.4 | Development of liaison nursing profiles to serve as a link and coordination between Primary Care and Dermatology (within the framework of rare disease actions) | 5.6 | 5.1 | 5.4 |

| 1.5 | Development and dissemination of guidelines/protocols for suspicion of GPP aimed at the ER staff | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 |

| 1.6 | Systems that facilitate rapid assessment of GPP patients at the ER through on-call dermatologists, training for on-call dermatology residents, on-call shifts, fast consultation channels, etc.) | 7.7 | 6.1 | 6.9 |

| 1.7 | Training in communication skills with the patient for optimal information transmission on the suspected diagnosis, symptom progression, steps the specialist will take, etc. Aimed at Dermatology professionals | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

| Code 2: Recommendations for diagnosis phase | ||||

| 2.1 | Development of guidelines with more precise criteria and diagnostic tests for GPP, for its differential diagnosis and associated complications (adding genetic studies and analytical tests) | 7.7 | 7.4 | 7.6 |

| 2.2 | Enable circuits to request priority tests based on consensus criteria | 6.9 | 5.9 | 6.4 |

| 2.3 | Establishment of result delivery time objectives by priority disease and monitoring/improvement systems for compliance | 6.3 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| 2.4 | Design and establishment of specific scales to objectify and measure the severity of GPP | 7.3 | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| 2.5 | Optimize the already established communication systems among Pathological Anatomy-Microbiology-Dermatology based on the characteristics of each center/area | 7.0 | 6.4 | 6.7 |

| 2.6 | Facilitate access to specialized psychological consultations when deemed necessary. Establish criteria for requesting consultation with specialized resources. Enable teleconsultation systems with specialized teams | 7.9 | 5.9 | 6.9 |

| 2.7 | Develop training initiatives on communication skills aimed at dermatologists with participation from specialized psychology | 7.4 | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| 2.8 | Facilitate access to dermatology nursing consultation (detailed information on the disease, service access, assessment of other patient dimensions, care plan, etc.) | 7.5 | 5.9 | 6.7 |

| 2.9 | Provide information about patient associations, resources, and available information sources after confirmatory diagnosis | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| Code 3: Recommendations for treatment phase | ||||

| 3.1 | Development of units/centers of expertise/support centers for complex psoriasis with specialized multidisciplinary teams to improve treatment management. Develop network work circuits, definition of criteria, access to e-consultations, etc. | 8.9 | 5.7 | 7.3 |

| 3.2 | Development of Dermatology nursing consultations: assessment of dimensions, personalized plan and objectives, training in self-care, risk factor and comorbidity control, lifestyle recommendations; alcohol, tobacco, diet, stress management, etc. | 7.4 | 5.7 | 6.6 |

| 3.3 | Facilitate access to treatments or clinical trials in cases of difficult control and management. Coordination actions with Hospital Pharmacy, dissemination of evidence, consensus of scientific societies access to specialized teams, etc. | 8.4 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| 3.4 | Development of treatment recommendations for patients in special situations (children, pregnant women, cancer patients, etc.) to guarantee quick access to treatment | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| 3.5 | Within the framework of developing joint Dermatology consultations with other specialties, facilitate the access of GPP patients to the necessary ones in case of comorbidities | 7.7 | 6.9 | 7.3 |

| 3.6 | Develop a GPP patient registry to establish studies and generate evidence | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.5 |

| 3.7 | Establish basic mental health screening focused on anxiety and depression for all patients through Dermatology or specialized nursing consultation | 7.5 | 6.4 | 7.0 |

| 3.8 | Define referral criteria to Mental Health or Psychology consultation | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.4 |

| 3.9 | Work on coordination systems with professionals responsible for authorizing temporary leaves. Work on standardizing reports to facilitate evaluation | 7.0 | 5.4 | 6.2 |

| Code 4: Recommendations for follow-up phase | ||||

| 4.1 | Develop and generalize the application of specific clinical and quality of life assessment scales for GPP. Application of BSA/GPPGA/GPPPASI assessment scales | 7.6 | 6.7 | 7.1 |

| 4.2 | Create consensus on therapeutic objectives for GPP (controlled/uncontrolled patient) | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| 4.3 | Establish rapid consultation systems with dermatology in case of worsening or adverse effects (information on warning symptoms, when to consult, direct phone line with dermatology for consultation or quick appointment) | 8.4 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| 4.4 | Training actions for patients on treatments, possible adverse effects, and action guidelines in case of a new outbreak | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.9 |

| 4.5 | Develop the role of case manager and ensure their inclusion in circuits for patients who could benefit (e.g., comorbidities) | 7.1 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

| 4.6 | Publicize resources and facilitate access to social workers in cases that require it | 7.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 |

| 4.7 | Facilitate access to information and resources on healthy lifestyle habits, nutrition, exercise, useful information for living with GPP, study follow-up, work, social and affectionate relationships, etc. | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| 4.8 | Facilitate access to specialized psychology in immune-mediated diseases | 8.1 | 5.0 | 6.6 |

| 4.9 | Develop specialized Dermatology nursing consultation | 8.3 | 4.7 | 6.5 |

| 4.10 | Work on standardizing medical evaluation reports for disability/incapacity. Promote the participation and specialization of Hospital Pharmacy | 7.5 | 6.3 | 6.9 |

| Code 5: General recommendations | ||||

| 5.1 | Establishment of specialized multidisciplinary units (rare diseases) with network work tools with reference hospitals | 8.1 | 6.3 | 7.2 |

| 5.2 | GPP patient registry and results follow-up | 8.4 | 8.0 | 8.2 |

| 5.3 | Specific guidelines/protocols for Dermatology, Primary Care, and the ER. Definition of suspicion, referral, inter-consultation criteria, etc., and rapid referral systems to Dermatology | 7.7 | 7.3 | 7.5 |

| 5.4 | Training and general awareness on the disease for all professionals involved | 7.9 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| 5.5 | Training in communication skills for Dermatology | 6.9 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| 5.6 | Access to specialized psychological support in immune-mediated diseases | 7.9 | 5.6 | 6.8 |

| 5.7 | Development of specialized nursing consultation in Dermatology | 8.4 | 5.1 | 6.8 |

| 5.8 | Contributions to the development and access to specific drugs for GPP. Evidence generation studies on usage and real-life outcomes, and protocols adapted to our environment | 8.8 | 7.1 | 8.0 |

| 5.9 | Creation of a web platform with information on the disease including podcasts, videos from professionals, patient experiences. Linked to a scientific society or patient association | 7.8 | 8.6 | 8.2 |

| 5.10 | Creation of a GPP patient community within Acción Psoriasis | 7.1 | 8.0 | 7.6 |

Recommendations shaded in gray are the 5 with the highest scores in the overall prioritization assessment (highest mean scores for impact and feasibility).

The current situation of GPP in Spain has been analyzed, and various recommendations have been made to offer better health care to these patients.

Unlike other common forms of psoriasis, GPP exhibits distinctive characteristics that shape the care and emotional needs of GPP patients.12,15–25

The approach to GPP falls within the general management of rare dermatological diseases. Priorities include the prevention and early detection of rare diseases, health care and social care, promoting research, and providing training and information to professionals and affected individuals and their families (reference to the Rare Diseases Plan of the Spanish National Health System). At European level, the goal is harmonization and equity through the European Rare Disease Action Plan, where the creation of networks (currently 24) helps move this goal forward. An example of this is the European Reference Network on Rare and Undiagnosed Skin Disorders (ERN-Skin).26,27

Defining the care and emotional journey of GPP patients has allowed the identification of needs and areas with room for improvement, while integrating the patient's perspective. Some needs are common to other rare and dermatological diseases and, therefore, can benefit from existing systems and resources.

Regarding the disease onset phase, key initiatives include increasing awareness of rare dermatological diseases and systems that facilitate rapid referral from Primary Care or the ER to Dermatology. In this regard, the development of tele-dermatology, in recent years, and its boost during the COVID-19 pandemic28,29 have made it a valuable tool for communication and quick access to consultation. This promotes shared access to available disease information among more experienced medical teams in the management of complex patients, better knowledge of referral criteria, and contributes, among other aspects, to the dissemination of training among health care workers across different levels of care. Tele-dermatology, shared health records, and dermatology inter-consultations are tools that could address communication, training, and access delay reduction needs.

Unlike other rare diseases, the delays in diagnosis times are not excessive. However, more protocolization on the necessary tests and less voluntarism in relationship and response times would be desirable.30 Improving access to genetic studies that can contribute to better understanding the disease at molecular level and individualizing treatment is also needed. Furthermore, training dermatologists in communication skills to better inform patients about their diagnosis is of paramount importance. The lack of communication competencies spans across various medical fields, not just Dermatology, and is especially noted in patients facing rare diseases, highlighting the need to strengthen effective communication across all areas of medicine from the patient's perspective.31–33

Regarding treatment, Spain currently lacks a specific medication for GPP, and off-label drugs with limited evidence are often used to fight this condition, which can lead to inefficiencies for the Spanish National Health System and result in heterogeneous approaches. Research initiatives to generate evidence on available drugs and developing new specific treatments that achieve better responses in a higher percentage of patients is desirable. In cases of poor response or high outbreak frequency, creating networks for case consultation with more experienced professionals and accessing specialized resources, including advanced practice nursing in Dermatology, psychological support, and clinical trial options, would be beneficial too. The creation of multidisciplinary committees for assessment and good communication and collaboration with the hospital pharmacy is essential to avoid unwanted delays and barriers to treatment access.

The development of dermatology nursing consultations can contribute to improvements at various levels: optimizing consultation time, informing and educating the patient, managing the disease, improving lifestyle habits, using scales, gathering patient experience information, and quickly accessing health care in case of doubtful or new outbreaks, among others.34,35

During the treatment and follow-up phases, guaranteeing a comprehensive approach to comorbidities is desirable, when necessary. Joint consultations or facilitating access to same-day appointments are solutions that yield good results and should be considered for GPP patients as well.

In the follow-up phase, actions to reduce patient uncertainty surrounding new outbreaks and improve their quality of life are desirable. Scales such as Body Surface Area (BSA), Pustular Psoriasis Physician Global Assessment (GPPGA), Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (GPPASI), or Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) will generate evidence and knowledge about treatment response, considering aspects of impact on the patients’ quality of life.36 Developing systems for measuring outcomes and experiences reported by dermatology patients (Patient-Reported Outcome Measures [PROM] and Patient-Reported Experience Measures [PREM]) will provide insights into the emotional impact of dermatological diseases.37–39

Generating evidence and knowledge is vital for rare diseases such as GPP. Developing patient registries and improving the coding and exploitation of electronic health record data and the application of artificial intelligence systems should be encouraged in our National Health System to facilitate better understanding of the disease.

Finally, initiatives that promote greater patient involvement and autonomy are needed. Collaboration between scientific societies and patient associations is essential for developing informative campaigns, accessing relevant and reliable information, and creating patient communities.

The result of this initiative provides a roadmap of priorities for health authorities, health care professionals, researchers, patients, and society that needs to be detailed and developed jointly in different health care contexts, adapting them to the various care models and available resources in each autonomous community.

MaterialsTo ensure an independent interpretation of the results of this project, the questionnaires supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

FundingThis study has been sponsored and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. Boehringer Ingelheim had the opportunity to review the manuscript to verify its medical and scientific accuracy regarding drugs or therapeutic areas of interest to BI, as well as intellectual property considerations. Ascendo Sanidad & Farma provided writing/editorial assistance while drafting this manuscript, contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflicts of interestR. Rivera declares having received payments/fees as a researcher, presenter, or advisor from Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer, BMS, INCYTE, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, UCB.

B. Muñoz Cabello declares having received payments/fees as a researcher, presenter, or advisor from Boehringer Ingelheim.

S. Ros Abarca declares having received payments/fees as a researcher, presenter, or advisor from Boehringer Ingelheim.