A 53-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, gout, obesity, and prior endoscopic ureteral lithotripsy consulted for painful skin lesions localized over the entire left thigh, ipsilateral flank and buttock, and the lumbosacral region. He reported having a fever and general malaise. Over the past 6 years, he had experienced similar episodes in the same location lasting 3 up to 7 days. Over the past 2 years, the outbreaks recurred every 4 to 8 weeks. Although, at times, he had been treated with systemic antibiotics due to suspected infectious cellulitis, this had no impact on the course of the disease. He said he did not have any other symptoms, constitutional syndrome, relevant family history, or association with drug intake. He did not meet any other criteria for familial Mediterranean fever either.

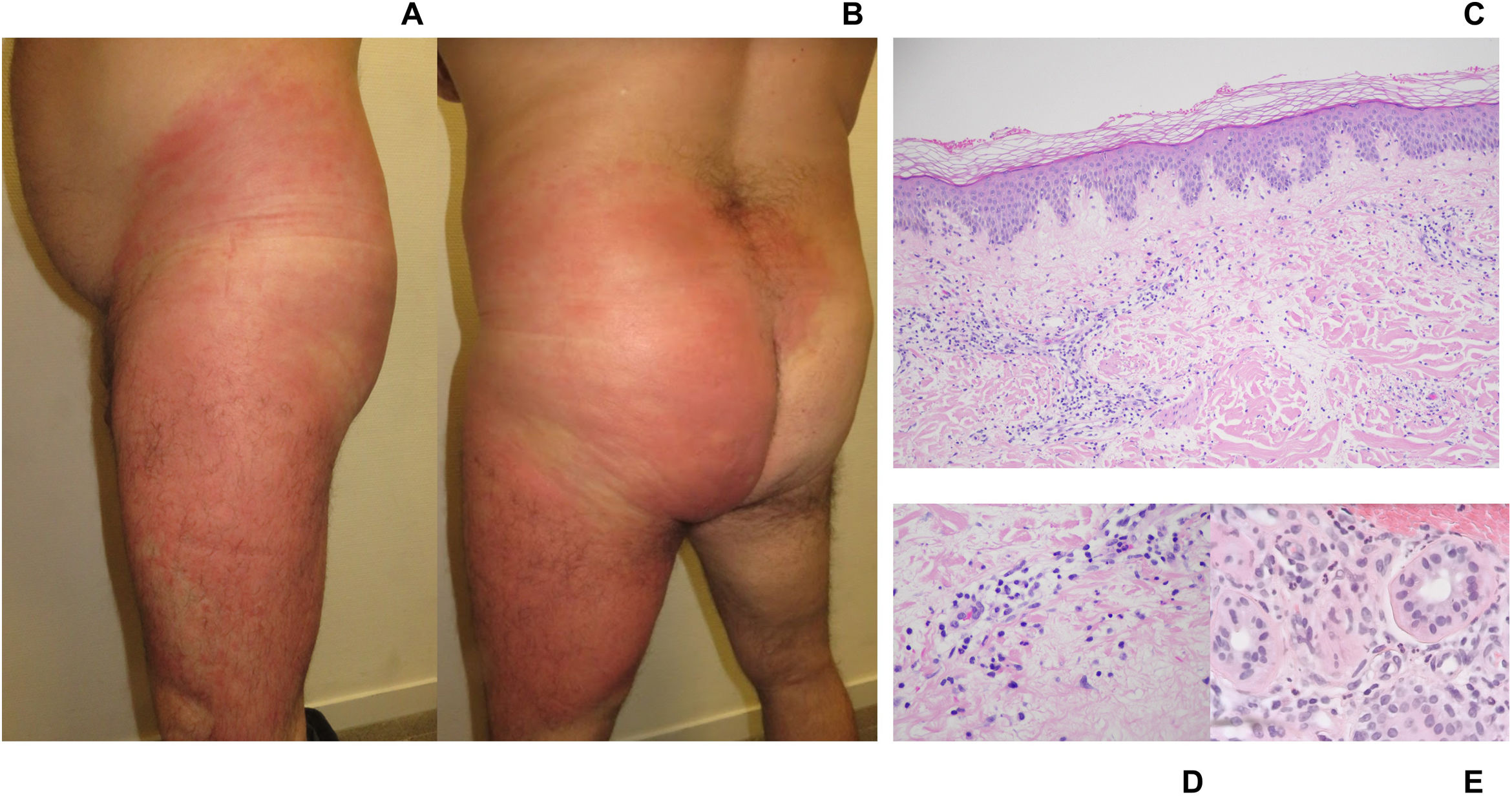

Upon examination, a large, well-demarcated, indurated, warm and painful erythematous plaque was revealed covering the above-mentioned areas (fig. 1A and B). A blood test revealed the presence of leukocytosis (11.98 x 109/L), neutrophilia (9.6 x 109/L; 80%), and an elevation of C-reactive protein (196mg/L). Other blood tests during remission periods showed no elevation in acute phase reactants. The remaining tests (tumor markers, autoimmunity, or serologies) revealed no significant findings.

A: clinical image. Left lateral view. Large erythematous plaque covering the entire left thigh and ipsilateral flank. Well-demarcated, indurated, and warm plaque. B: clinical image. Posterior view. Erythematous-edematous plaque. Left thigh, buttock, and flank involvement; confluent toward the lumbosacral region. C: histological image. Overview. Skin with superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with neutrophils. Mild papillary dermal edema and preserved epidermis. No evidence of panniculitis or vasculitis. No eosinophils seen. Original Image 4X. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. D: histological image. Detail of inflammatory infiltrate. Papillary dermis with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Presence of neutrophils. Original Image 20X. Hematoxylin-eosin stain. E: histological image. Detail of periadnexal infiltrate. Periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils. Original Image 20X. Hematoxylin-eosin stain.

Histological examination of a biopsy taken from the affected area (fig. 1C-E) revealed the presence of skin with mild papillary edema and superficial and periadnexal perivascular lymphocytic inflammation, also with the presence of neutrophils. No vasculitis or leukocytoclastic phenomena were reported. Although histology proved atypical, the clinicopathological correlation suggested the diagnosis of giant cellulitis-like Sweet syndrome (GCSS).

Initial treatment with oral corticosteroids and colchicine proved ineffective. Dapsone at a dose of 50mg daily was then administered, resulting in excellent control of the outbreaks. After gradually tapering the dose over a 9-month period, treatment was eventually discontinued. To date, no new outbreaks have occurred, and no associated comorbidities have appeared. An endoscopic ureteral lithotripsy—laterality consistent with the lesions—performed 1-2 months before symptom onset could have acted as a trigger.

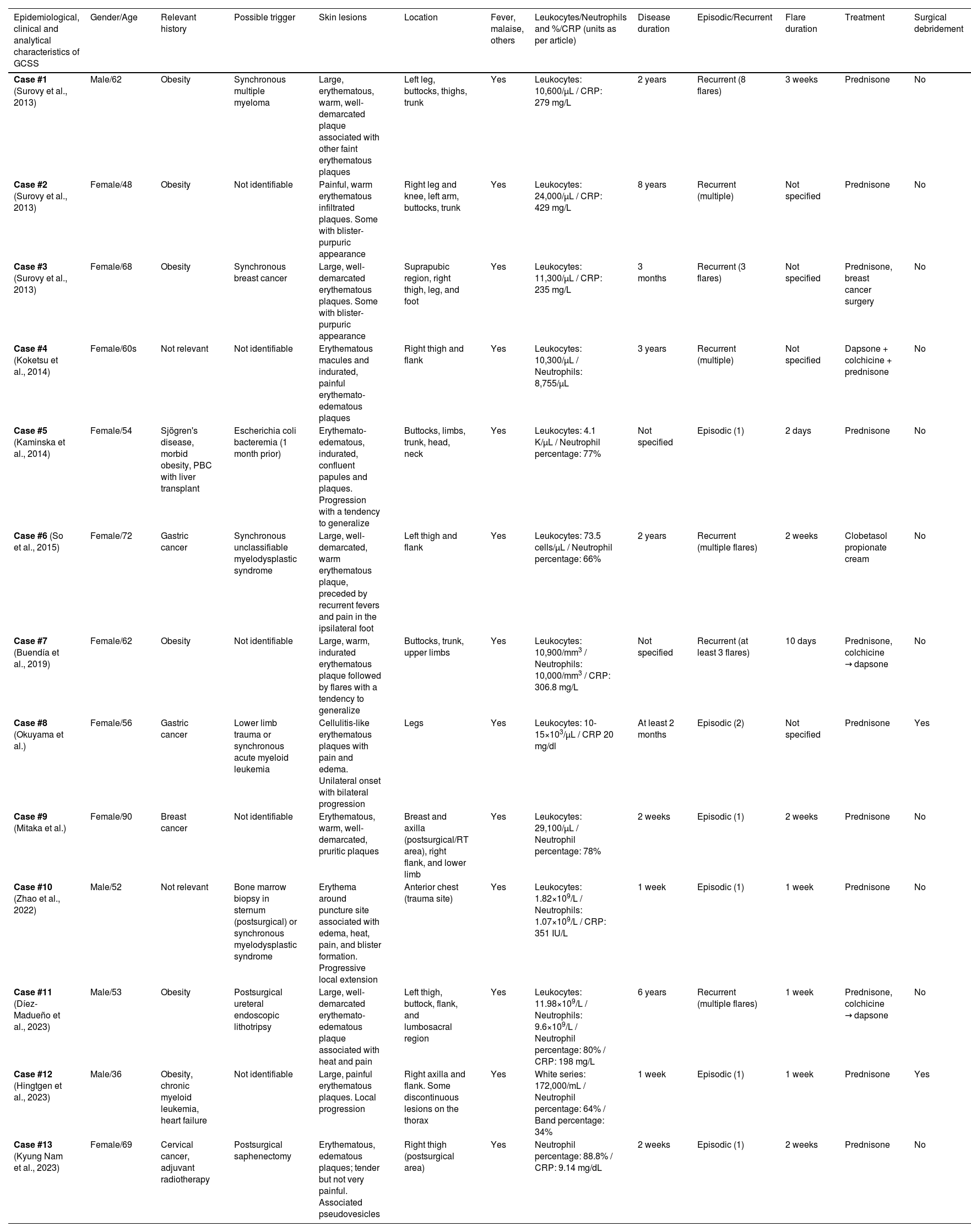

Multiple clinical and histological variants of Sweet syndrome (SS) have been described to date. Surovy et al. described a rare variant in 2013, which they called “GCSS”.1 In our review (Pubmed/other sources), we found 9 articles and 1 poster, representing an exceptional SS subtype (Table 1).1–9 The articles report on 9 women and 4 men (N=13) aged between 36 and 90 years (median, 62). Notable past medical histories include the presence of neoplasms and obesity. Possible triggers described include hematological and solid organ neoplasms, trauma, or bacterial infection.

Conceptual table summarizing the epidemiological, clinical, and analytical characteristics of GCSS cases described in the current literature.

| Epidemiological, clinical and analytical characteristics of GCSS | Gender/Age | Relevant history | Possible trigger | Skin lesions | Location | Fever, malaise, others | Leukocytes/Neutrophils and %/CRP (units as per article) | Disease duration | Episodic/Recurrent | Flare duration | Treatment | Surgical debridement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case #1 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Male/62 | Obesity | Synchronous multiple myeloma | Large, erythematous, warm, well-demarcated plaque associated with other faint erythematous plaques | Left leg, buttocks, thighs, trunk | Yes | Leukocytes: 10,600/μL / CRP: 279 mg/L | 2 years | Recurrent (8 flares) | 3 weeks | Prednisone | No |

| Case #2 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Female/48 | Obesity | Not identifiable | Painful, warm erythematous infiltrated plaques. Some with blister-purpuric appearance | Right leg and knee, left arm, buttocks, trunk | Yes | Leukocytes: 24,000/μL / CRP: 429 mg/L | 8 years | Recurrent (multiple) | Not specified | Prednisone | No |

| Case #3 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Female/68 | Obesity | Synchronous breast cancer | Large, well-demarcated erythematous plaques. Some with blister-purpuric appearance | Suprapubic region, right thigh, leg, and foot | Yes | Leukocytes: 11,300/μL / CRP: 235 mg/L | 3 months | Recurrent (3 flares) | Not specified | Prednisone, breast cancer surgery | No |

| Case #4 (Koketsu et al., 2014) | Female/60s | Not relevant | Not identifiable | Erythematous macules and indurated, painful erythemato-edematous plaques | Right thigh and flank | Yes | Leukocytes: 10,300/μL / Neutrophils: 8,755/μL | 3 years | Recurrent (multiple) | Not specified | Dapsone + colchicine + prednisone | No |

| Case #5 (Kaminska et al., 2014) | Female/54 | Sjögren's disease, morbid obesity, PBC with liver transplant | Escherichia coli bacteremia (1 month prior) | Erythemato-edematous, indurated, confluent papules and plaques. Progression with a tendency to generalize | Buttocks, limbs, trunk, head, neck | Yes | Leukocytes: 4.1 K/μL / Neutrophil percentage: 77% | Not specified | Episodic (1) | 2 days | Prednisone | No |

| Case #6 (So et al., 2015) | Female/72 | Gastric cancer | Synchronous unclassifiable myelodysplastic syndrome | Large, well-demarcated, warm erythematous plaque, preceded by recurrent fevers and pain in the ipsilateral foot | Left thigh and flank | Yes | Leukocytes: 73.5 cells/μL / Neutrophil percentage: 66% | 2 years | Recurrent (multiple flares) | 2 weeks | Clobetasol propionate cream | No |

| Case #7 (Buendía et al., 2019) | Female/62 | Obesity | Not identifiable | Large, warm, indurated erythematous plaque followed by flares with a tendency to generalize | Buttocks, trunk, upper limbs | Yes | Leukocytes: 10,900/mm3 / Neutrophils: 10,000/mm3 / CRP: 306.8 mg/L | Not specified | Recurrent (at least 3 flares) | 10 days | Prednisone, colchicine → dapsone | No |

| Case #8 (Okuyama et al.) | Female/56 | Gastric cancer | Lower limb trauma or synchronous acute myeloid leukemia | Cellulitis-like erythematous plaques with pain and edema. Unilateral onset with bilateral progression | Legs | Yes | Leukocytes: 10-15×103/μL / CRP 20 mg/dl | At least 2 months | Episodic (2) | Not specified | Prednisone | Yes |

| Case #9 (Mitaka et al.) | Female/90 | Breast cancer | Not identifiable | Erythematous, warm, well-demarcated, pruritic plaques | Breast and axilla (postsurgical/RT area), right flank, and lower limb | Yes | Leukocytes: 29,100/μL / Neutrophil percentage: 78% | 2 weeks | Episodic (1) | 2 weeks | Prednisone | No |

| Case #10 (Zhao et al., 2022) | Male/52 | Not relevant | Bone marrow biopsy in sternum (postsurgical) or synchronous myelodysplastic syndrome | Erythema around puncture site associated with edema, heat, pain, and blister formation. Progressive local extension | Anterior chest (trauma site) | Yes | Leukocytes: 1.82×109/L / Neutrophils: 1.07×109/L / CRP: 351 IU/L | 1 week | Episodic (1) | 1 week | Prednisone | No |

| Case #11 (Díez-Madueño et al., 2023) | Male/53 | Obesity | Postsurgical ureteral endoscopic lithotripsy | Large, well-demarcated erythemato-edematous plaque associated with heat and pain | Left thigh, buttock, flank, and lumbosacral region | Yes | Leukocytes: 11.98×109/L / Neutrophils: 9.6×109/L / Neutrophil percentage: 80% / CRP: 198 mg/L | 6 years | Recurrent (multiple flares) | 1 week | Prednisone, colchicine → dapsone | No |

| Case #12 (Hingtgen et al., 2023) | Male/36 | Obesity, chronic myeloid leukemia, heart failure | Not identifiable | Large, painful erythematous plaques. Local progression | Right axilla and flank. Some discontinuous lesions on the thorax | Yes | White series: 172,000/mL / Neutrophil percentage: 64% / Band percentage: 34% | 1 week | Episodic (1) | 1 week | Prednisone | Yes |

| Case #13 (Kyung Nam et al., 2023) | Female/69 | Cervical cancer, adjuvant radiotherapy | Postsurgical saphenectomy | Erythematous, edematous plaques; tender but not very painful. Associated pseudovesicles | Right thigh (postsurgical area) | Yes | Neutrophil percentage: 88.8% / CRP: 9.14 mg/dL | 2 weeks | Episodic (1) | 2 weeks | Prednisone | No |

Disease is characterized by outbreaks—lasting days to weeks—featuring large, confluent, well-demarcated erythematous-edematous plaques, associated with fever and general malaise. Lesions can be warm, painful, and pruritic. They may begin in a localized area and then spread locally or affect multiple areas. Initially, lesions can mimic bacterial cellulitis, so patients are sometimes hospitalized and treated with antibiotics, or surgical treatment. The most widely affected areas are the lower limbs, buttocks, and trunk. Regarding the duration and frequency of the outbreaks, 2 forms of presentation seem to emerge. One shows a recurrent pattern,7 with multiple episodes over months or even years. The second form has an episodic pattern,6 with 1 or 2 self-limited episodes over a period of weeks to months.

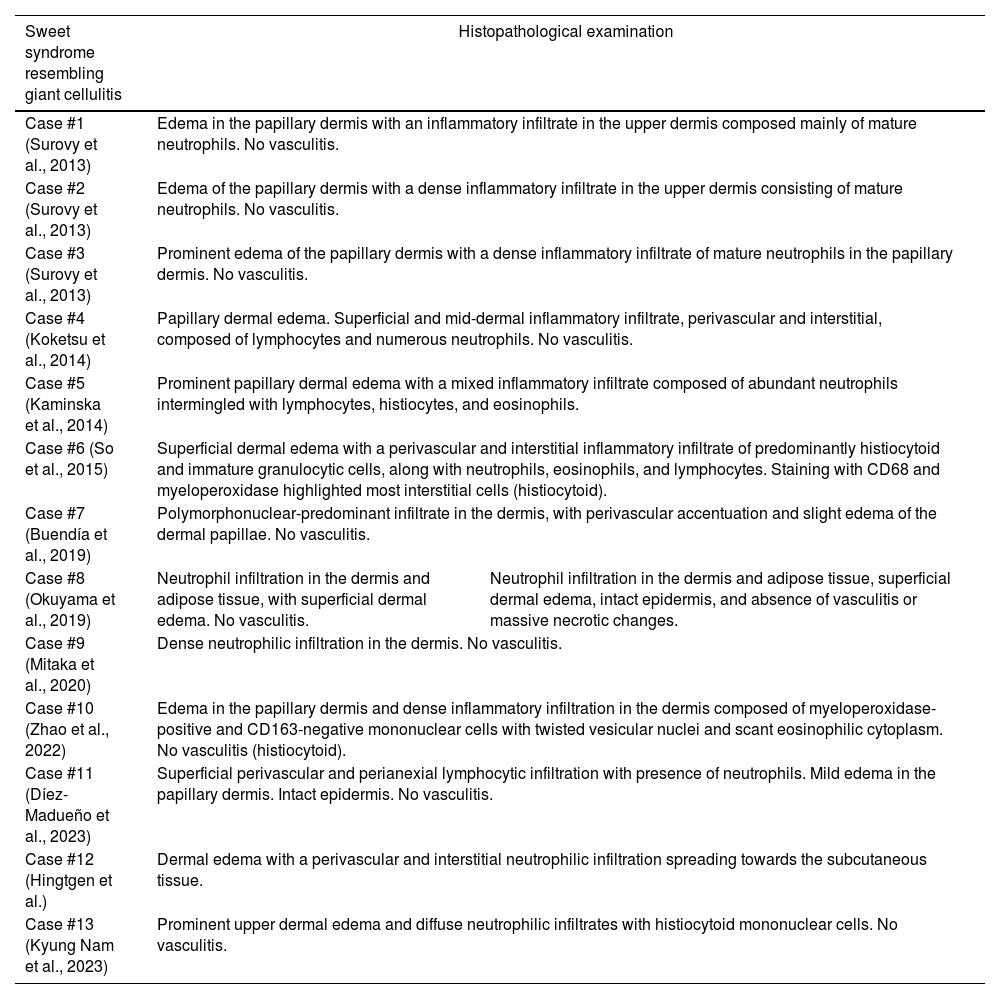

Blood tests during outbreaks show leukocytosis, neutrophilia, or elevated acute phase reactants. Histological features are shown in Table 2.

Table summarizing the histological characteristics of GCSS cases described in the current literature.

| Sweet syndrome resembling giant cellulitis | Histopathological examination | |

|---|---|---|

| Case #1 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Edema in the papillary dermis with an inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis composed mainly of mature neutrophils. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #2 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Edema of the papillary dermis with a dense inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis consisting of mature neutrophils. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #3 (Surovy et al., 2013) | Prominent edema of the papillary dermis with a dense inflammatory infiltrate of mature neutrophils in the papillary dermis. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #4 (Koketsu et al., 2014) | Papillary dermal edema. Superficial and mid-dermal inflammatory infiltrate, perivascular and interstitial, composed of lymphocytes and numerous neutrophils. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #5 (Kaminska et al., 2014) | Prominent papillary dermal edema with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of abundant neutrophils intermingled with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. | |

| Case #6 (So et al., 2015) | Superficial dermal edema with a perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate of predominantly histiocytoid and immature granulocytic cells, along with neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes. Staining with CD68 and myeloperoxidase highlighted most interstitial cells (histiocytoid). | |

| Case #7 (Buendía et al., 2019) | Polymorphonuclear-predominant infiltrate in the dermis, with perivascular accentuation and slight edema of the dermal papillae. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #8 (Okuyama et al., 2019) | Neutrophil infiltration in the dermis and adipose tissue, with superficial dermal edema. No vasculitis. | Neutrophil infiltration in the dermis and adipose tissue, superficial dermal edema, intact epidermis, and absence of vasculitis or massive necrotic changes. |

| Case #9 (Mitaka et al., 2020) | Dense neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #10 (Zhao et al., 2022) | Edema in the papillary dermis and dense inflammatory infiltration in the dermis composed of myeloperoxidase-positive and CD163-negative mononuclear cells with twisted vesicular nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm. No vasculitis (histiocytoid). | |

| Case #11 (Díez-Madueño et al., 2023) | Superficial perivascular and perianexial lymphocytic infiltration with presence of neutrophils. Mild edema in the papillary dermis. Intact epidermis. No vasculitis. | |

| Case #12 (Hingtgen et al.) | Dermal edema with a perivascular and interstitial neutrophilic infiltration spreading towards the subcutaneous tissue. | |

| Case #13 (Kyung Nam et al., 2023) | Prominent upper dermal edema and diffuse neutrophilic infiltrates with histiocytoid mononuclear cells. No vasculitis. | |

The diagnosis of GCSS is one of exclusion, and differential diagnosis should include the following entities: bacterial cellulitis, eosinophilic cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, autoinflammatory syndromes, or atypical SS subtypes (e.g., necrotizing fasciitis-type SS).10 The presentation of large plaques with atypical characteristics, asymmetrical distribution affecting multiple areas, negative cultures, and the lack of response to antibiotics help distinguish it from bacterial cellulitis.

Treatment is similar to that used to treat classic SS, often responding to corticosteroids. In non-responsive cases, dapsone is considered an effective drug.

Localized neutrophilic dermatosis triggered by tissue injury (LNDT) is a recently described umbrella term used to unify cases of SS triggered by trauma, surgery, lymphedema, or chronic venous insufficiency (whether primary or secondary).11 In our opinion, both GCSS and LNDT share traits that suggest they could be presentations of the same autoinflammatory syndrome. The 2 entities exhibit skin lesions, fever, and general malaise occurring in episodic or recurrent outbreaks, which can affect a localized area or become generalized. Differently, in LNDT, the lesions are predominantly limited to the affected tissue or area—usually the lower limb or postoperative region—with multi-territory involvement being less frequent. GCSS, therefore, remains a concept still under definition. New publications are necessary to properly define this entity.

Understanding GCSS helps in the early suspicion of the disease, distinguishing it from bacterial cellulitis, thus avoiding multiple hospital admissions, prolonged antibiotic use, and unnecessary surgical interventions.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.