The Atlas of Clinical Images of the Skin and Skin Diseases (hereafter, the Atlas) grew out of author José Eugenio Olavide's desire to provide a practical, illustrated guide to dermatology in the 19th century. In this work Dr Olavide conveyed the wealth of his knowledge of skin diseases acquired through observations made after he took charge of the wards at the specialist Hospital San Juan de Dios in 1860.

Olavide summed up the opportunity his position at the hospital afforded thus: “A clinic with 120 beds that are always occupied is a great natural museum, where the eye soon grows accustomed to discerning the minute details of different skin diseases.”

In his 1871† prologue to his illustrated textbook on general clinical dermatology (Dermatología general, clínica iconográfica de las enfermedades de la piel o dermatosis), hereafter referred to as General Dermatology, Olavide described his purpose in 1871 as follows: Reading through several texts on dermatology in the hope of quick learning left me more and more confused. The descriptions of skin diseases I found in traditional textbooks had made me imagine presentations that I did not find in the clinic, and vice versa. What impressed me when I found myself facing a patient did not correspond to the images of diseases that purely theoretical studies had formed in my mind.

Olavide went on to describe how he conceived his Atlas: I necessarily started out by waiting for my eye to become familiar with the varied, heterogeneous aspects of skin diseases and then note similarities and differences in order to develop principles. Only then did the textbooks become useful to me. I recorded my observations, and although today I see diagnostic errors among them, I kept at it. By putting them together and collating them with my theoretical studies, I developed a body of work and an approach. I then decided the time had come to start making new, more detailed and more practical observations that would be more graphic and impossible to erase from memory.

The illustrations were born of this effort, created only with the idea of having a small museum in my own office, because I was unaware of any possibility of publishing a volume of such proportions with my own resources. Nor did I have hopes for any kind of official support.”

The illustrations that Olavide refers to in this foreword form part of his aforementioned General Dermatology and the Atlas. Gathered together are Olavide's lessons, conferences, and observations collected over a long period of time, though not immediately published. The completed body of work is a rich, complex resource that merits exhaustive study and a separate article. In the present paper we will limit ourselves to briefly summarizing its content.

The completed work is bound in 2 volumes. The first one contains nearly all the text pertaining to Olavide's General Dermatology and is itself divided into 2 parts. The first part, from 1871, comprises 170 pages of preliminary discussion plus a so-called analytical index or table of contents, and 9 plates illustrating concepts in general dermatology. The plates compare anatomical lesions or basic structures. The second part of this first volume consists of 27 clinical lessons on skin diseases published over the years. Six lessons are on parasitic diseases (from 1873), 7 discuss pseudo-exanthematous conditions (from 1874), and 14 concern constitutional diseases with skin involvement (from 1880).

The second volume is the Atlas proper. It comprises 166 chromolithographs illustrating skin diseases, most of them drawn from patients observed directly on the wards of Hospital San Juan de Dios. Detailed comments — in the style of notes typically found in a patient's medical history — accompany each plate. The edition described here is credited to publisher José Gil Dorregaray in 1873.

Various persons contributed to producing this very complex work during different stages in the publication process. José Acevedo illustrated what he saw during direct observation of hospitalized patients. He also undertook the printing of some of the chromolithographs. Some of the plates were printed by others; the surnames credited are Kraus, Soldevilla, Llanta, and Rufflé. The histologic illustrations in the first volume were prepared by Federico Rubio y Galí from drawings by Peiró Rodrigo. As mentioned, José Gil Dorregaray was named as publisher. J. Mateu y Dommon, in Madrid, was the printer.

During our restoration of the illustrations over the past 12 years, which took place in the context of restoring many other objects in the Olavide Museum, two plates (IV and V) in the Atlas called our attention because they were quite different from the rest. They were in the section on spontaneous local skin diseases or deformities.

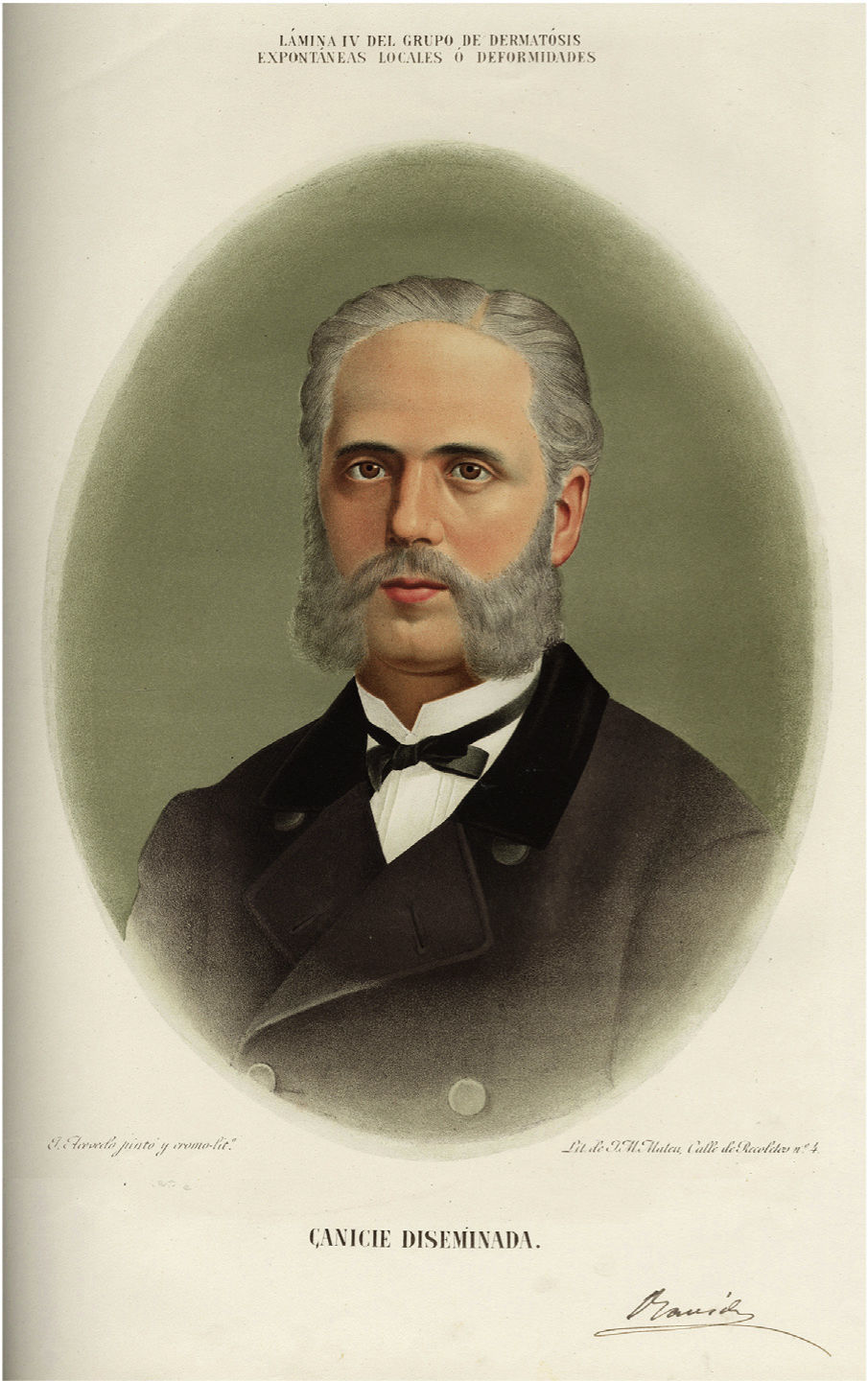

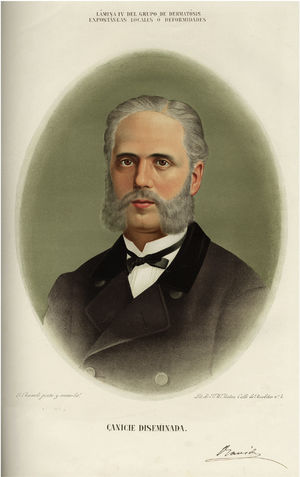

Both were frontal portraits of a man wearing a dark jacket, a shirt, and a bow tie. He was drawn against a light green background. In both plates the portrait is centered on the page within an oval field, according to the custom of the time. Care has been taken with the quality of the drawing as well as the printing. No medical history concerning the skin conditions named accompanies either of these illustrations.

One of the plates, given the simple caption “disseminated canities” (Fig. 1), took us greatly by surprise when we realized how much the man shown resembles Dr Olavide himself, judging by photographs of him from obituaries or donated by the family. The photographs are on file in the museum's archives. Moreover, below the portrait, on the right, the handwritten notation “Olavide” appears, encouraging us to hypothesize that the author decided to include his own portrait in the Atlas, one of his most important works.

Material and MethodsWe gathered all the photographs of Dr Olavide we could locate in our museum, which holds donations from his family (Fig. 2). We also examined photographs known to be in other collections.I

In addition, we sought several more copies of the 1873 Atlas so that different prints of the portrait could be compared.

Four were available for comparison. The Royal National Academy of Medicine had 2 copies of the work, and our Olavide Museum had 1 copy plus a set of unbound plates and pages. An additional 11 copies were located. Seven belonged to the medical faculty of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and 4 more were found in the private collections of dermatologists.

We describe these copies of the Atlas as follows:

Copy 1Atlas belonging to the Royal National Academy of Medicine

Author: José Eugenio Olavide

Publisher: José Gil Dorregaray, Madrid, 1873

Physical description: Large format 52×39×8.5cm (height×width×spine thickness)

Leather- and cloth-bound over cardboard. Gold-embossed green leather spine.

Markings: Dedication to the Royal Academy, inscribed “the author” (el autor)

Copy 2Atlas belonging to the Royal National Academy of Medicine

Author: José Eugenio Olavide

Publisher: José Gil Dorregaray, Madrid, 1873

Description: Large format 52×39×8.5cm (height×width×spine thickness)

Leather- and paper-bound over cardboard. Marbled paper on the cover, leather on the spine and corners, and gold-embossed lettering and decoration on the spine.

Copy 3Atlas belonging to the Olavide Museum

Author: José Eugenio Olavide

Printer: T. de Fortanet, Madrid, 1873

Description: Large format 52×39×8.5cm (height×width×spine thickness)

Bound in red leather and cloth over cardboard. Gold-embossed lettering and paneled border with botanical motifs, gilt-edged pages, and silk corner guards.

Copy 4Unbound plates from the Atlas belonging to the Olavide Museum.

Interested contemporary readers acquired copies of the Atlas in installments, or fascicles. Therefore, most variation between copies occurred over an extended period and became evident in the ordering of the plates during the binding process. The illustrations should properly be inserted according to their numbering and the order described in the index, or table of contents, but when copies are compared, the sequencing does not always coincide.

Furthermore, the same binding technique is not used from one copy to another. Some bindings are more elaborate and costly, boasting many gold-embossed decorative details as can be seen on the one in the Olavide Museum. Others are bound more soberly and economically. Although the simpler copies are also hardbound, the cardboard is covered with marbled paper, as is the second copy described above.

Having described the physical features of each copy of the Atlas, we will now discuss our discovery of the inclusion of what we believe to be the portrait of José Eugenio Olavide in his own work. To that purpose we applied the same tools we use routinely in the museum.

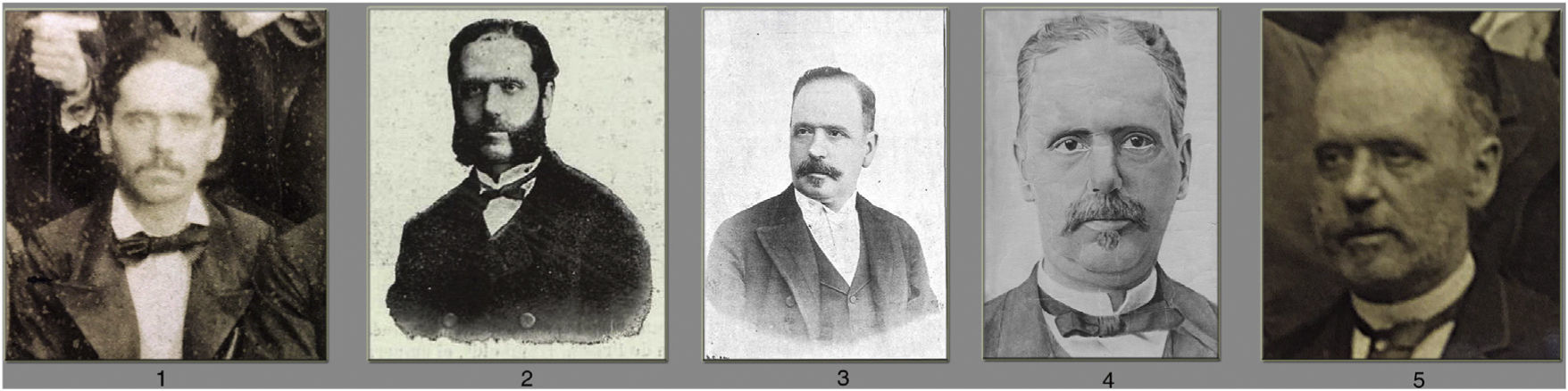

We examined all the available photographs (as opposed to caricatures or sketches) of Dr Olavide, as follows:

- 1.

Detail extracted from a group photograph of the graduating class of 1857–1858. (Reproduced with the permission of the Illustrious College of Physicians of Madrid. Photographer unknown.

- 2.

Photograph from the magazine Iris, Barcelona, March 16, 1901, p. 12. Photographer unknown.

- 3.

Photograph from the magazine La Ilustración Española y Americana (an illustrated magazine of places in Spain and the Latin America), Madrid, March 15, 1901, p. 10. Photographer: Company.

- 4.

Undated photograph provided by the family of Dr Olavide. Photographer unknown.

- 5.

Photograph taken during the First International Dermatology Conference in Paris in 1889. Provided by the museum of the Hôpital Saint Louis, París.

All the images were used to study the facial characteristics as they appeared over time and from different angles, even though only the first and fifth photographs were dated. Olavide was 21 or 22 years old when the first was taken and 53 years old when the fifth was taken.

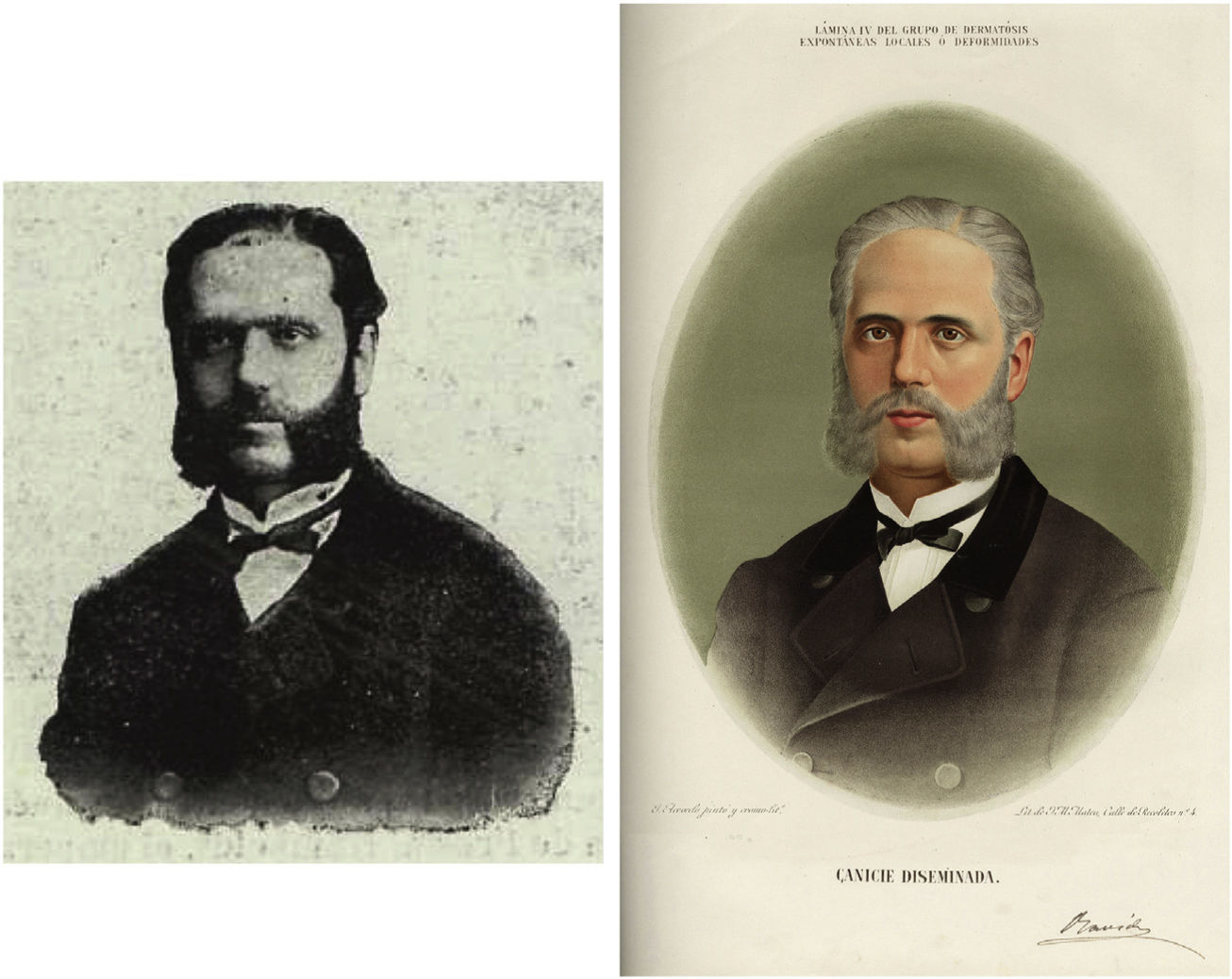

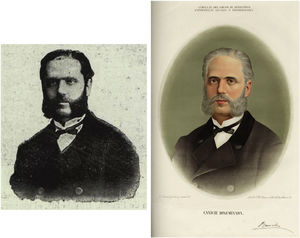

Most interesting was the second photograph published in a 1901 issue of Iris. Taken by an unknown photographer, it is the only one in which Dr Olavide has long sideburns joining a mustache to form a Hulihee beard, coinciding with the style of beard shown in the illustration of disseminated canities in the section on spontaneous local skin diseases or deformities (Fig. 3).

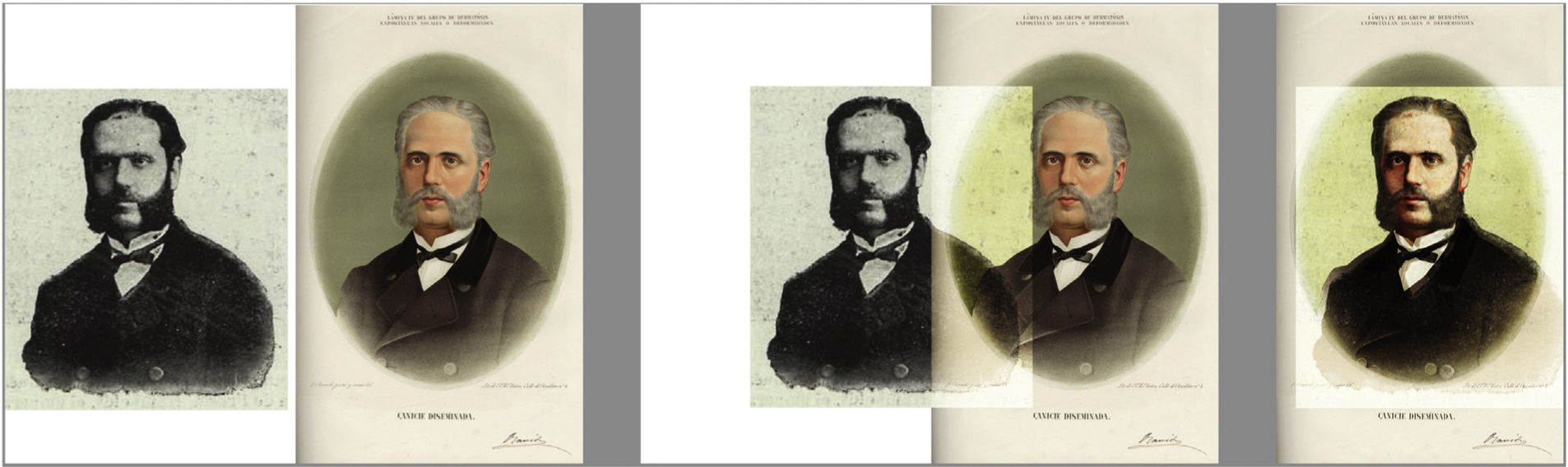

That photograph and the illustration in the Atlas were digitized for comparison in a program for editing and graphic design (Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended, Version 12.1, 64 bits). The images were resized and the opacity of the magazine photograph was reduced to create a semitransparent version that could be superimposed over the digitized illustration from the Atlas. This process showed that the main facial features in the Iris photograph of Olavide (oval face, hairline, ears, form of the eyes and distance between them, shape of the nose, mouth and chin) coincided almost perfectly with the features in the lithograph. The only differences between the 2 portraits were in the height of the shoulders and position of the shirt, therefore affecting the upper part of the trunk, as can be seen in Fig. 4.

Even the buttons on the jacket, the type of shirt, and the unusual form of the bow tie seem to be the same. We can say almost certainly that the portrait carefully drawn and reproduced by José Acevedo for the Atlas was based on this photograph of Olavide.

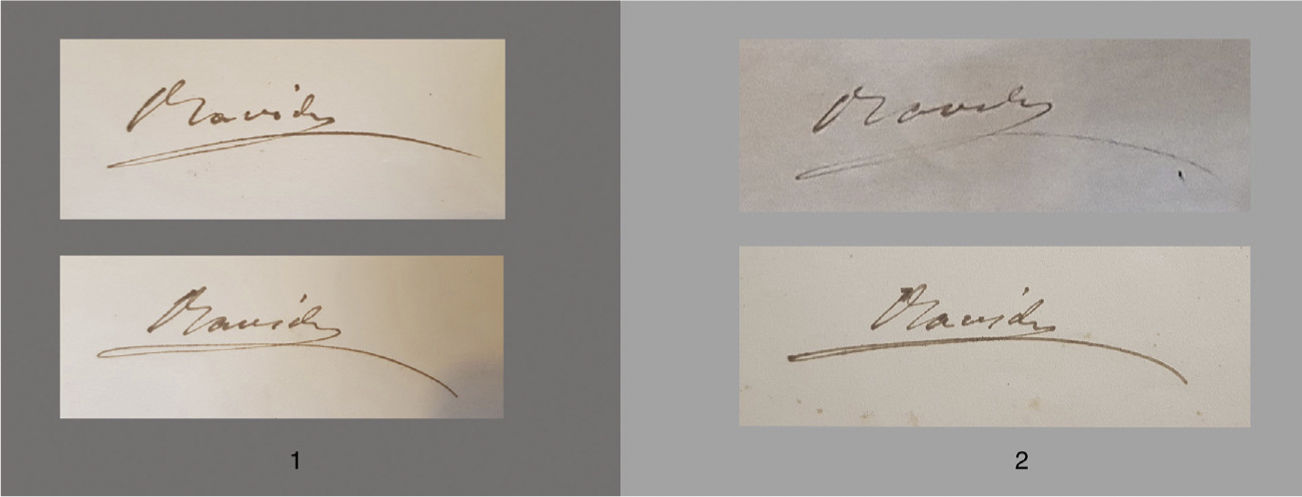

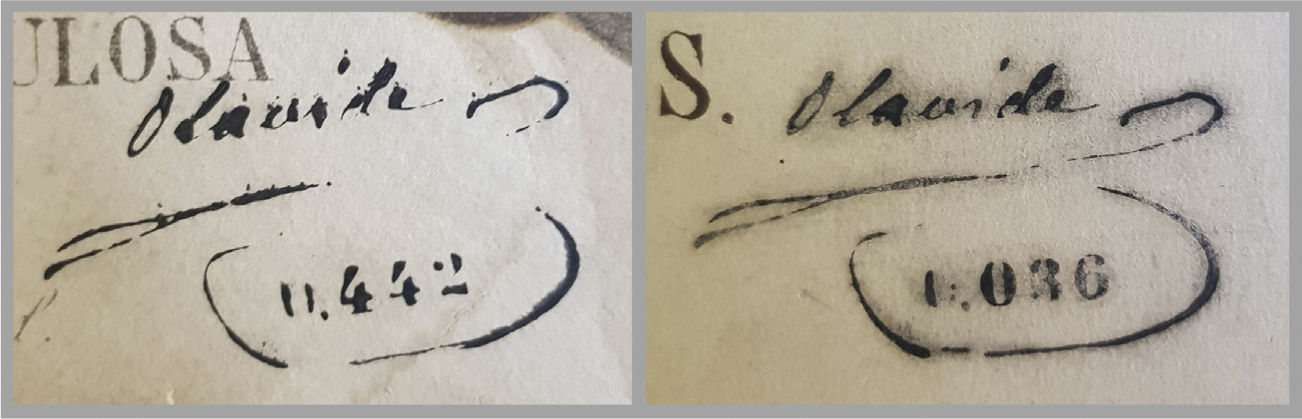

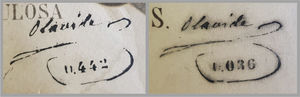

Moreover, an inscription — the author's name — is written on the plates captioned as "disseminated canities" in all 11 copies of the Olavide Atlas we were able to compare. These inscriptions should not be confused with the stamped signatures and series numbers that appear on some of the other lithographs (Figs. 5 and 6).

Based on these comparisons, even in the absence of conclusive anthropomorphic evidence, we believe we have supported our hypothesis that José Eugenio de Olavide y Landazábal inserted his own portrait into his Atlas, probably an indication of the satisfaction he must have felt on its publication.

The practice of placing an author's portrait, often a photograph, on the frontispiece facing the title page of a book was not unusual in this period.

What is singular in this case is that the apparent portrait of Olavide appears on one of the middle pages of the volume and presents the author as just another patient with a so-called local disease or deformity rather than as the author of the book. His signature is unmistakable, however, and we invite readers who have access to a copy of the 1873 Atlas to examine this interesting illustration and look for these details.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We especially thank Dr Emilio del Río de la Torre for his contributions and suggestions during the writing of this article. Without his historical research on the beginnings of dermatology and the figure of Olavide, the present research could not have been carried out. We are also grateful for his interest in and commitment to the Olavide Museum.

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar L, Aranda-Gabrielli D, Maruri-Palacín A. ¿Olavide en el «Olavide»? Nuevas aportaciones al Atlas de la clínica iconográfica de la piel o dermatosis. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2019;110:859–860.

Olavide's 2-volume work was published and acquired by readers over time in fascicles, as explained on p. 2. Therefore, some of the dates the author provides in this article refer to years when certain fascicles became available. (Translator: M. E. Kerans)