Macular amyloidosis (MA) is a skin condition with predominance in young women. We aimed to evaluate quality of life (QoL) and psychopathologies in these patients. In this cross-sectional study, patients with MA referring to the Imam Reza Hospital, Mashhad during 2018–2020, and their matched controls were included. Participants completed the 36-item short form survey (SF-36), the revised symptom checklist-90 (SCL-90-R), and the dermatology life quality index (DLQI). Overall, 40 women with a mean age of 36.80±10.19 years were studied. In the MA group, the SF-36 score was lower (P<0.001), and the SCL-90-R score was higher (P<0.001). The DLQI score was correlated with age (r=0.447; P=0.048) and pruritus severity (r=0.776; P<0.001), and was lower in patients with uncovered lesions (P=0.005). MA was associated with impaired QoL, which was determined by pruritus severity and lesion location; these patients can benefit from psychiatric interventions in this regard.

La amiloidosis macular (AM) es una situación cutánea con predominancia en mujeres jóvenes. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la calidad de vida (QoL) y las psicopatologías en estos pacientes. En este estudio transversal se incluyó a pacientes con AM derivados al Hospital Imam Reza, de Mashhad, de 2018 a 2020, así como a sus controles pareados. Los participantes completaron la encuesta SF-36 (formulario breve de 36 ítems), el test de los 90 síntomas revisado (SCL-90-R) y el índice de calidad de vida en dermatología (DLQI). A nivel global, se estudió a 40 mujeres con una edad media de 36,80±10,19 años. En el grupo AM, la puntuación SF-36 fue más baja (p<0,001), siendo más alta la puntuación SCL-90-R (p<0,001). La puntuación DLQI se correlacionó con la edad (r=0,447; p=0,048) y con la severidad del prurito (r=0,776; p<0,001), siendo más baja en las pacientes con lesiones sin cubrir (p=0,005). La AM estuvo asociada a un deterioro de la QoL, que vino determinada por la severidad del prurito y la localización de la lesión. A este respecto, dichas pacientes pueden beneficiarse de intervenciones psiquiátricas.

Macular amyloidosis (MA) is the most common type of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA).1 It typically presents in the upper back or the extremities forming pruritic regions with undefined borders.1 The treatment options for PLCA are diverse but still not definitive.2 Since somatic symptom relief is not an immediately achievable end, it is important to consider the psychological comorbidities of PLCA.

MA is often associated with pruritus, which can potentially limit patients’ functioning, comparable to chronic pain.3 Furthermore, MA lesions are esthetically displeasing and may cause stigmatization, particularly considering the higher prevalence in women.4 Therefore, it is important to consider MA's impact on psychosocial performance and quality of life (QoL), even though the disease is not clinically severe. So far, only one study has investigated this matter, reporting social and emotional role limitations and mental health decline.5 This study was aimed to investigate QoL and the extent of psychopathologies in Iranian patients with MA. The results of this study can be of particular interest, since Iran's unique culture and dress code makes skin lesions normally covered in public.

Patients and methodsStudy settings and approvalThis cross-sectional, two-group study was conducted during 2018–2020 at the outpatient dermatology clinic of Imam Reza Hospital of Mashhad. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants and confidentiality was ensured. The Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences approved this study (Code: IRAN.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1397.125).

ParticipantsConvenience sampling resulted in 20 participants with MA, who met the inclusion criteria: confirmed diagnosis of MA through histopathology and physical examination by a dermatologist, <65 years of age, and literacy. Using available sampling, 20 healthy age- and sex-matched volunteers were selected from the general population through an online invitation, as the control group. Patients with major pre-existing mental conditions (prior to MA), systemic amyloidosis and unrelated chronic physical illnesses were not included.

Data collectionThe case group completed three questionnaires: the 36-item short from survey (SF-36), the revised symptom checklist-90 (SCL-90-R) and the dermatology life quality index (DLQI). The control group only completed SF-36 and SCL-90-R. The validated Persian version of all three questionnaires were used.6–8The SCL-90-R is a self-report survey across nine dimensions, with greater scores representing more severe conditions. Three global variables are also measured by this survey: the global severity index (GSI) measures the extent of an individual's psychiatric conditions, the positive symptom total (PST) indicates the total number of questions with a score greater than zero, and the positive symptom distress index (PSDI) is calculated by dividing the sum of all items by PST.7

The DLQI is a self-administered questionnaire that measures the impacts of skin disease on QoL, focusing on six dimensions, with higher scores signifying greater QoL impairments.6 The SF-36 is a self-report questionnaire, measuring QoL across 8 subscales, with higher scores indicating better quality of life.9

Additionally, data including age, sex, marital status, education, employment, duration of disease, location of lesions, severity of pruritus (based on the visual analog scale [VAS]), history of psychiatric disease or hospitalization, substance abuse, and physical illnesses were recorded for each participant.

Statistical analysisAll data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Statistics, Chicago, IL). Means and standard deviations were used to describe the data, while t-test, Mann–Whitney, and Chi-square tests were used to compare variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test of normality, the Spearman's, and Pearson's tests were used. The alpha level was 0.05 for all tests.

ResultsIn total, 40 female participants (20 in each study group) with an average age of 36.80±10.19 years (ranging 13–53 years) were included. Based on t-test and Chi-square test, the case and control groups were not significantly different in age (P=0.668), marital status, education, employment, or family history of similar disease. The average disease duration was 5.05±3.30 years (ranging 1–12). Regarding lesion location in the case group (n=20), eight (40%) were covered (back or torso), four (20%) were uncovered (head, neck, or upper limbs), and eight (40%) were both. The mean pruritus severity was 5.30±3.46: score-0 (n=3, 15%); score-1 (n=2, 10%); score-2 (n=1, 5%); score-6 (n=4, 20%); score-7 (n=7, 35%); score-8 (n=2, 10%); score-10 (n=1, 5%).

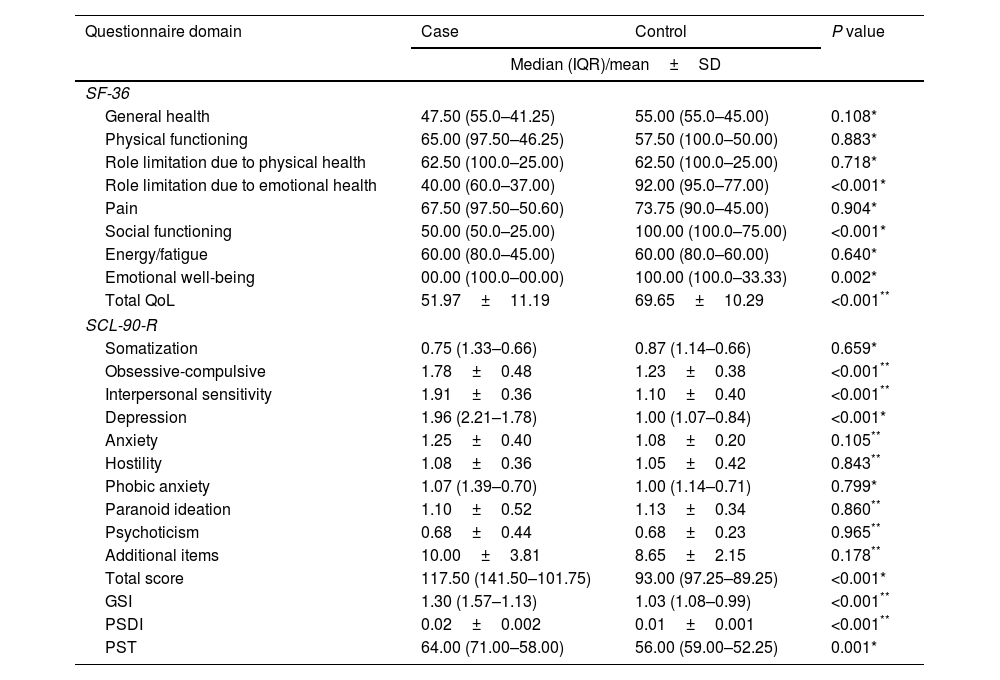

According to Table 1, the SF-36 score was significantly greater in the control group; total (P<0.001) and in three subscales: role limitation due to emotional health (P<0.001), social functioning (P<0.001), and emotional well-being (P=0.002). Regarding the SCL-90-R scores, the case group had greater total scores, as well as, the ‘depression’, ‘obsessive-compulsive’ and ‘interpersonal sensitivity’ dimensional scores (P<0.001). Furthermore, GSI, PSDI and PST were significantly higher in the case group (P<0.001).

Comparison of the SF-36 and SCL-90-R results between study groups.

| Questionnaire domain | Case | Control | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR)/mean±SD | |||

| SF-36 | |||

| General health | 47.50 (55.0–41.25) | 55.00 (55.0–45.00) | 0.108* |

| Physical functioning | 65.00 (97.50–46.25) | 57.50 (100.0–50.00) | 0.883* |

| Role limitation due to physical health | 62.50 (100.0–25.00) | 62.50 (100.0–25.00) | 0.718* |

| Role limitation due to emotional health | 40.00 (60.0–37.00) | 92.00 (95.0–77.00) | <0.001* |

| Pain | 67.50 (97.50–50.60) | 73.75 (90.0–45.00) | 0.904* |

| Social functioning | 50.00 (50.0–25.00) | 100.00 (100.0–75.00) | <0.001* |

| Energy/fatigue | 60.00 (80.0–45.00) | 60.00 (80.0–60.00) | 0.640* |

| Emotional well-being | 00.00 (100.0–00.00) | 100.00 (100.0–33.33) | 0.002* |

| Total QoL | 51.97±11.19 | 69.65±10.29 | <0.001** |

| SCL-90-R | |||

| Somatization | 0.75 (1.33–0.66) | 0.87 (1.14–0.66) | 0.659* |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 1.78±0.48 | 1.23±0.38 | <0.001** |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 1.91±0.36 | 1.10±0.40 | <0.001** |

| Depression | 1.96 (2.21–1.78) | 1.00 (1.07–0.84) | <0.001* |

| Anxiety | 1.25±0.40 | 1.08±0.20 | 0.105** |

| Hostility | 1.08±0.36 | 1.05±0.42 | 0.843** |

| Phobic anxiety | 1.07 (1.39–0.70) | 1.00 (1.14–0.71) | 0.799* |

| Paranoid ideation | 1.10±0.52 | 1.13±0.34 | 0.860** |

| Psychoticism | 0.68±0.44 | 0.68±0.23 | 0.965** |

| Additional items | 10.00±3.81 | 8.65±2.15 | 0.178** |

| Total score | 117.50 (141.50–101.75) | 93.00 (97.25–89.25) | <0.001* |

| GSI | 1.30 (1.57–1.13) | 1.03 (1.08–0.99) | <0.001** |

| PSDI | 0.02±0.002 | 0.01±0.001 | <0.001** |

| PST | 64.00 (71.00–58.00) | 56.00 (59.00–52.25) | 0.001* |

SF-36: the 36-item short from survey; SCL-90-R: the revised symptom checklist-90; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; QoL: quality of life; GSI: global symptom index; PSDI: positive symptom distress index; PST: positive symptom total.

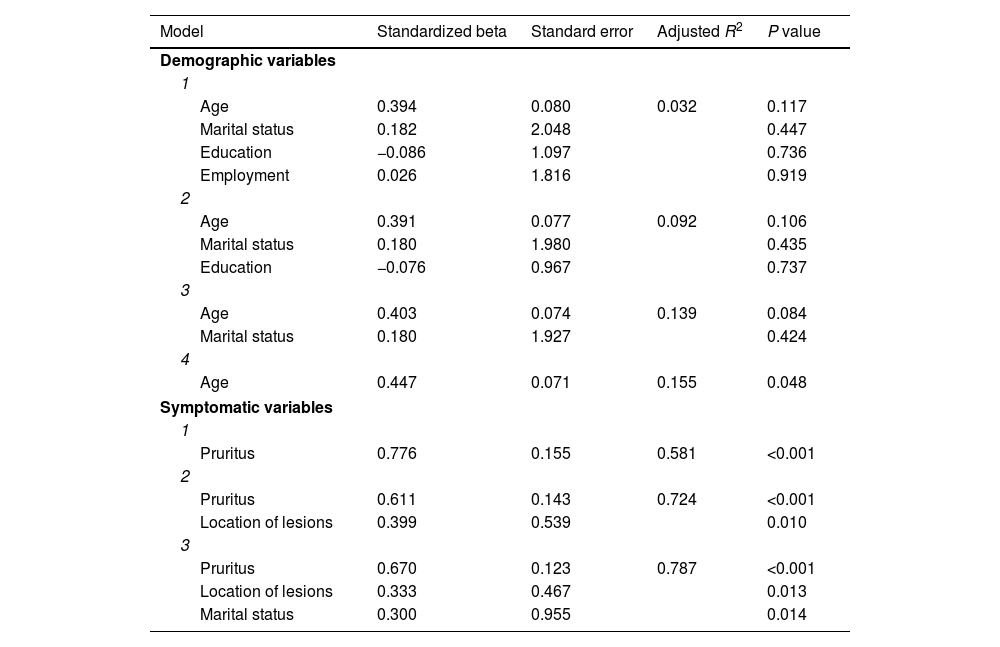

The case group answered the DLQI survey (Supplementary Table 1) resulting in a mean score of 10.95±3.60 (ranging 3–19). Accordingly, the effect on QoL in this group (n=20) was very large in ten (50.0%), moderate in nine (45.0%), and small in one (5.0%) case. Table 2 demonstrates the results of linear regression models, indicating that age can significantly predict DLQI score. Furthermore, after being adjusted, pruritus severity, location of lesions and marital status could significantly predict DLQI as much as 78%. Linear regression found no significant relationship between the SCL-90-R and SF-36 scores and the demographic or symptomatic features.

Linear regression models of the relationship DLQI score and different variables.

| Model | Standardized beta | Standard error | Adjusted R2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| Age | 0.394 | 0.080 | 0.032 | 0.117 |

| Marital status | 0.182 | 2.048 | 0.447 | |

| Education | −0.086 | 1.097 | 0.736 | |

| Employment | 0.026 | 1.816 | 0.919 | |

| 2 | ||||

| Age | 0.391 | 0.077 | 0.092 | 0.106 |

| Marital status | 0.180 | 1.980 | 0.435 | |

| Education | −0.076 | 0.967 | 0.737 | |

| 3 | ||||

| Age | 0.403 | 0.074 | 0.139 | 0.084 |

| Marital status | 0.180 | 1.927 | 0.424 | |

| 4 | ||||

| Age | 0.447 | 0.071 | 0.155 | 0.048 |

| Symptomatic variables | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| Pruritus | 0.776 | 0.155 | 0.581 | <0.001 |

| 2 | ||||

| Pruritus | 0.611 | 0.143 | 0.724 | <0.001 |

| Location of lesions | 0.399 | 0.539 | 0.010 | |

| 3 | ||||

| Pruritus | 0.670 | 0.123 | 0.787 | <0.001 |

| Location of lesions | 0.333 | 0.467 | 0.013 | |

| Marital status | 0.300 | 0.955 | 0.014 | |

DLQI: the dermatology life quality index.

Age was positively correlated with DLQI score (P=0.048; r=0.447), and the pain subscale of SF-36 was correlated with pruritus severity (P=0.018; r=0.521) and the DLQI score (P=0.044; r=0.455). In addition to these, pruritus severity was correlated negatively with paranoid ideation (P=0.027; r=0.521) and positively with DLQI score (P<0.001; r=0.776).

According to one-way analysis of variance, the DLQI score was not different between the married and single groups (P=0.236), while it was significantly different (P=0.001) between the three lesion location groups (covered; uncovered; and both). Tukey's test showed that patients with covered lesions had a higher QoL, compared with the other two groups (P<0.05).

DiscussionControlling somatic symptoms and accompanying psychological comorbidities has been acknowledged as an important element of disease management in recent years. Here, we used multiple questionnaires to investigate the impact of MA on mental health and QoL. Similar to our findings, Fang et al. discovered low SF-36 scores in the dimensions of emotional well-being, social functioning, and role limitation due to emotional health, among PLCA patients.5 The mean DLQI score in our study was higher than what Fang et al. reported (9.05±3.88); however, this is not surprising since we only investigated one subtype of PLCA and our sample size was limited in comparison.

DLQI score among PLCA patients has been reported in few studies. A study recorded the preliminary DLQI among MA and lichen simplex patients as a secondary outcome reporting a mean score of 8.25±10.5.10 A study on DLQI among females with acquired skin pigmentations showed that 40% of MA patients were very largely affected while 33.3% were moderately affected.11 We found that the mean DLQI score among MA patients was 10.95±3.60, while studies in similar populations indicate that this score in psoriasis, vitiligo, acne and burn injury is 6.46,12 7.05,6 6.4213 and 17.7,14 respectively. These demonstrate that MA is comparatively more impactful on QoL; however, it is worth noting that based on DLQI scores, most patients in our study (>90%) were experiencing very large to moderate effects. Furthermore, our findings of the DLQI score indicated a greater impairment of QoL in patients with uncovered lesions, which is in line with previous reports.15

No study had previously investigated the SCL-90-R in MA patients; however, compared with a healthy population, the total SCL-90-R is reportedly greater in patients affected by chronic pruritic skin lesions, with more prominent difference in the ‘obsessive-compulsive’ and the ‘depression’ dimensions.16 MA is a condition often accompanied by chronic pruritus, and as such, our findings are in line with studies on pruritic conditions.4,17 Pruritus is comparable to chronic pain3 and it can lead to sleep disorders, which can lead to depressive and anxious symptoms, ultimately reducing QoL.18

Even though, we found that older patients experience a greater impact on their QoL, studies with more diverse populations have concluded that younger age is associated with a greater impact on QoL among patients with PLCA and other skin conditions.5,19 Younger people, particularly women, appear to be more self-conscious about their physical image compared with older people, and they can have a harder time dealing with their condition, signifying the importance of a simultaneous psychiatric and symptomatic approach.

This study was the first in this region to evaluate the mental health implications of PLCA, although some limitations were present. We employed convenience sampling and did not incorporate treatment progress and stage of disease as variables into our analysis. Furthermore, due to our limited sample size, it was not feasible to adequately examine the variables predicating the impact of QoL on MA using logistic regression. Nonetheless, our study indicated that MA patients have an impaired QoL, which can be influenced by factors such as age, severity of pruritus, and the location of skin lesions (covered or uncovered). Our findings may signify the value of a multidisciplinary approach to patients with MA.

FundingThis work was financially supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences [grant number 970178].

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

This study is based on a thesis by Dr. Atieh Kaveh for the doctorate degree in medicine (MD).