The figure of José Eugenio de Olavide y Landazábal is well known to readers: his life, books, and other publications have been the focus of several articles.1–4 Dr. Olavide's book of aphorisms—those brief, doctrinal sentences that propose a general rule in a science or art—is perhaps one of the less well-known of his many works.3

To comprehend the meaning of Olavide's aphorisms, we should bear in mind 2 aspects of his view of science. First, Olavide gave credit to postulates that describe a constitutional theory of health, as expressed in the following 3 affirmations2:

- 1.

Disease is a ‘state of a man’ as a whole, not of one of the parts of his body.

- 2.

We cannot speak, therefore, of diseases of the skin, except when these have external causes (i.e., diseases from parasites or other agents).

- 3.

“In all other cases, a skin lesion is not itself the disease but merely its manifestation.”

Second, Olavide classified skin diseases as follows:

- 1.

Diseases of known causes, which are zooparasitic or phytoparasitic.

- 2.

Natural, or spontaneous, diseases, which are general, or constitutional.

- 3.

Artificial diseases, or those externally caused.

This article briefly discusses Olavide's views of the practice of dermatologic therapy, as it is expressed through his aphorisms.

MethodsWe studied Olavide's Aphorisms on the Practice of Dermatology.5 The cover (Fig. 1) names him as Sr. Dr. D. José Eugenio Olavide, and the publisher is given as the printing establishment of the Real Hospicio de San Fernando (Oficina Tipográfica del Hospicio) in Madrid. The year of publication was 1880.

Results and DiscussionOlavide's aphorisms were published in the series of semiannual monographs issued by the Specialist Journal of Ophthalmology, Syphilology, Dermatology and Urinary Diseases (Revista Especial de Oftalmología, Sifiliografía, Dermatología y Afecciones Urinarias). Each monograph cost 1 Spanish peseta (1000 pesetas=€6). A journal page advertising the monographs included the habitual warning that no credit would be extended to enquiring parties and that orders for the monograph would not be processed unless accompanied by payment.

The author is described on the cover (Fig. 1) as a physician of Madrid's Hospital de San Juan de Dios and of the royal household, a member of the Royal Academy of Medicine, and decorated with the Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished American Order of Isabel the Catholic, among other honors. Dr. Olavide himself described the collection of aphorisms for the practice of dermatology as “a loose collection of ideas about diseases of the skin presented in no particular order,” suggesting that they were jotted down whenever and however they occurred to him “on the fly,” which is to say he wrote them quickly, improvising and expressing his ideas without stopping to review or revise and without any premeditated structure or logical order that is evident.

The monograph brings together 257 aphorisms on 49 pages. We found 13 that are relevant to topical treatments (Table 1) and 12 that are relevant to spa therapies (Table 2).

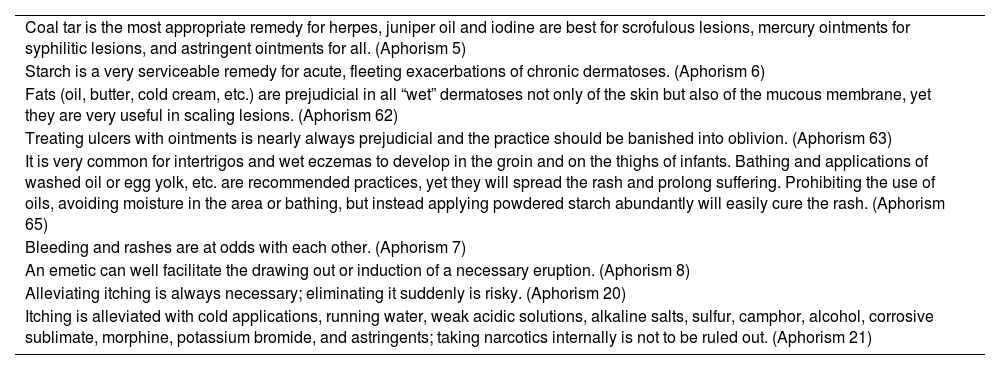

Aphorisms Relevant to Topical Treatments.

| Coal tar is the most appropriate remedy for herpes, juniper oil and iodine are best for scrofulous lesions, mercury ointments for syphilitic lesions, and astringent ointments for all. (Aphorism 5) |

| Starch is a very serviceable remedy for acute, fleeting exacerbations of chronic dermatoses. (Aphorism 6) |

| Fats (oil, butter, cold cream, etc.) are prejudicial in all “wet” dermatoses not only of the skin but also of the mucous membrane, yet they are very useful in scaling lesions. (Aphorism 62) |

| Treating ulcers with ointments is nearly always prejudicial and the practice should be banished into oblivion. (Aphorism 63) |

| It is very common for intertrigos and wet eczemas to develop in the groin and on the thighs of infants. Bathing and applications of washed oil or egg yolk, etc. are recommended practices, yet they will spread the rash and prolong suffering. Prohibiting the use of oils, avoiding moisture in the area or bathing, but instead applying powdered starch abundantly will easily cure the rash. (Aphorism 65) |

| Bleeding and rashes are at odds with each other. (Aphorism 7) |

| An emetic can well facilitate the drawing out or induction of a necessary eruption. (Aphorism 8) |

| Alleviating itching is always necessary; eliminating it suddenly is risky. (Aphorism 20) |

| Itching is alleviated with cold applications, running water, weak acidic solutions, alkaline salts, sulfur, camphor, alcohol, corrosive sublimate, morphine, potassium bromide, and astringents; taking narcotics internally is not to be ruled out. (Aphorism 21) |

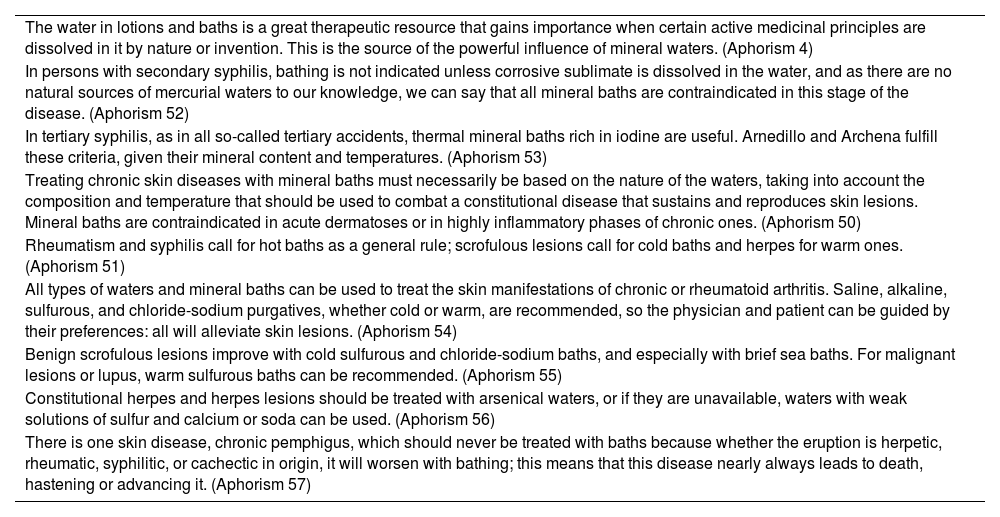

Aphorisms Relevant to Spa Therapies.

| The water in lotions and baths is a great therapeutic resource that gains importance when certain active medicinal principles are dissolved in it by nature or invention. This is the source of the powerful influence of mineral waters. (Aphorism 4) |

| In persons with secondary syphilis, bathing is not indicated unless corrosive sublimate is dissolved in the water, and as there are no natural sources of mercurial waters to our knowledge, we can say that all mineral baths are contraindicated in this stage of the disease. (Aphorism 52) |

| In tertiary syphilis, as in all so-called tertiary accidents, thermal mineral baths rich in iodine are useful. Arnedillo and Archena fulfill these criteria, given their mineral content and temperatures. (Aphorism 53) |

| Treating chronic skin diseases with mineral baths must necessarily be based on the nature of the waters, taking into account the composition and temperature that should be used to combat a constitutional disease that sustains and reproduces skin lesions. Mineral baths are contraindicated in acute dermatoses or in highly inflammatory phases of chronic ones. (Aphorism 50) |

| Rheumatism and syphilis call for hot baths as a general rule; scrofulous lesions call for cold baths and herpes for warm ones. (Aphorism 51) |

| All types of waters and mineral baths can be used to treat the skin manifestations of chronic or rheumatoid arthritis. Saline, alkaline, sulfurous, and chloride-sodium purgatives, whether cold or warm, are recommended, so the physician and patient can be guided by their preferences: all will alleviate skin lesions. (Aphorism 54) |

| Benign scrofulous lesions improve with cold sulfurous and chloride-sodium baths, and especially with brief sea baths. For malignant lesions or lupus, warm sulfurous baths can be recommended. (Aphorism 55) |

| Constitutional herpes and herpes lesions should be treated with arsenical waters, or if they are unavailable, waters with weak solutions of sulfur and calcium or soda can be used. (Aphorism 56) |

| There is one skin disease, chronic pemphigus, which should never be treated with baths because whether the eruption is herpetic, rheumatic, syphilitic, or cachectic in origin, it will worsen with bathing; this means that this disease nearly always leads to death, hastening or advancing it. (Aphorism 57) |

Before focusing on Dr. Olavide's aphorisms on treatments, we mention 2 of them that sum up his opinion on why many physicians have trouble treating skin diseases. The first states his view of certain colleagues baldly: “many physicians are afraid to treat skin diseases because they don’t know how” (aphorism 24). The second qualifies that statement, explaining that “sometimes they themselves have no fear, but they instill it in their patient to cover for their own inaction or ignorance” (aphorism 25).

Olavide states that the approach to treating a condition must depend on whether it is acute or chronic: “wise waiting is the great remedy for acute skin diseases” (aphorism 1), whereas “chronic skin diseases should be fought with internal and external remedies. The first type neutralize maladies within the patient, whether known or unknown, because fortunately there exist treatments even for conditions whose natures are still a mystery. Treating them also serves to halt the gradual progression of constitutional changes, which sustain, or reproduce, processes that become chronic. The second type (topical treatments) check the progression of the local malady—which is to say, the skin lesion, which is almost always a symptom of an altered constitution” (aphorism 2). Olavide adds that “there are numerous other treatments of noteworthy value in special cases that cannot be applied generally without creating problems” (aphorism 3).

Some of the aphorisms on topical therapies listed in Table 1 express principles that we might well share today, while others no longer have a place in our therapeutic arsenal.

Olavide was a great proponent of spa therapy, for which he particularly recommended the Spanish spas of Archena, in Murcia, and Arnedillo, in La Rioja, for treating skin diseases. Table 2 brings together his aphorisms on the use of their resources. He never missed a chance to give his opinion about the veracity of certain notions advocated by lay practitioners who were inexpert in skin problems. Thus, he says, “a common opinion of non-experts, and of many physicians too, when presented with a chronic rash, is to fail to take time for a deeper, more detailed look before calling the eruption herpes, and then to recommend avoiding topical treatments so the herpes does not go further inside. Their only advice is to take sulfurous baths in summer. A routine like that is ridiculous and out of step with the scientific advances of our day” (aphorism 64). Or, he wonders, “What ridiculous notion underlies the common belief that patients should take no baths in spa waters?” (aphorism 66). Or, he asks, “Is there any common sense in seeking a radical cure for a skin condition that has been present for many years, just by spending 7 or 9 days taking the waters and bathing?” (aphorism 67).

The monograph ends with aphorism 257, dedicated to what we might call the new treatments of those times. Perhaps they seem completely dated to us now, but Olavide and his follow dermatologists logically enthused that “today dermatology has two new topical medications, pyrogallic acid and chrysophanic acid, which offer advantages over coal tar and juniper oil to combat psoriasis, pityriasis and all dry skin diseases or conditions in phases of desiccation or peeling. They should be mixed with butter in a ratio of 5 to 100 to create an ointment to rub gently into the eruption once a day.”

Conclusions- 1.

The Aphorisms of Dr. José Eugenio Olavide is a historical document that sheds light on the practices of Spanish dermatology at the end of the 19th century.

- 2.

Some of the doctor's aphorisms continue to be relevant today.

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.