Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and CD4+ counts <200cells/μL are more vulnerable to opportunistic infections that can generate challenging presentations with potential misdiagnosis. A systematic approach could prevent errors in complex cases.

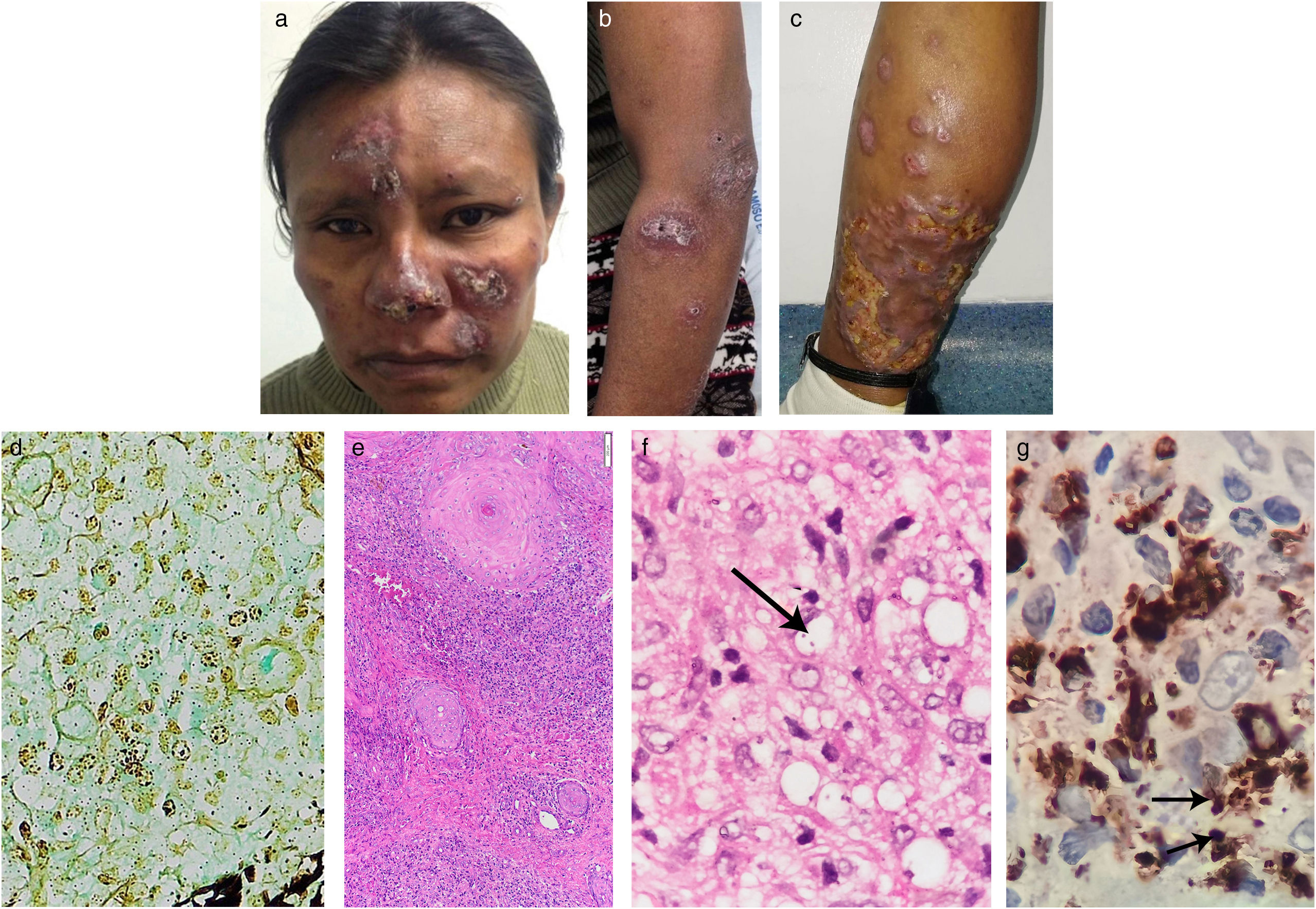

A 40-year-old woman from a tropical rainforest region on inpatient care for an acute diarrheal disease was referred to us for a 2-year history of multiple skin lesions that appeared on her lower left limb with subsequent ulceration, followed by similar lesions on the face and upper limbs. She had been diagnosed with HIV 2 years before and had poor adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Physical examination revealed brown erythematous nodules and plaques with hematic crusts on her face, anterior forearms, and legs (Fig. 1a–c). No mucosal lesions or lymphadenopathies were found. Laboratory tests showed showed an HIV viral load of 446,816copies/mL and a CD4+ count of 152cells/μL. Chest and abdominal CT scans were normal. Skin biopsy revealed a dermal granulomatous nodular dermatitis suggestive of Histoplasma infection due to positive Gomori structures within histiocytes (Fig. 1d). Treatment with liposomal amphotericin B (total dose of 1080 mg) for 8 days followed by itraconazole 200 mg/day for 14 days was given, with clinical improvement.

Brownish erythematous plaques on the face (A). Violaceous plaques on left forearm and arm (B). Nodules and a large erythematous infiltrated plaque on the posterior lower left leg with areas of ulceration (C). Positive Gomori structures within histiocytes (Gomori staining, 40×). (D) Granulomatous nodular inflammatory process consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and some plasma cells in the upper and deep dermis (H&E staining, 10×). (E) Leishmania amastigote, arrow (H&E staining, 600×). (F) Anti-CD68 (clone KP1) immunohistochemistry showing intense cytoplasmic positivity in macrophages. In addition, some amastigotes can be observed, arrows (IHQ, 600×) (G).

One month later, the patient returned with increased infiltration of lesions and a negative urinary Histoplasma antigen test, thus weakening the initial diagnosis. A second skin biopsy showed granulomatous nodular dermatitis, intracellular organisms consistent with amastigotes, an intense anti-CD68 cytoplasmic positivity (Fig. 1e–g), and a negative Gomori stain. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed the presence of Leishmania, subgenus Viannia. Further chest and abdominal CT scans were again normal. Cultures and histopathology examination from skin and transbronchial pulmonary biopsies were negative for fungi.

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) was diagnosed and liposomal amphotericin B was restarted in view of the previous good response, to complete a total dose of 2200mg, achieving cutaneous improvement.

At the 3-month follow-up, skin lesions developed a warty appearance, which was deemed a sign of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in view of adequate adherence to HAART, HIV viral load of 110copies/mL, CD4+ count of 500cells/μL, and a skin biopsy negative for amastigotes. Consequently, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed. Subsequently, after her last hospital discharge, the patient was lost to follow-up.

DCL is a rare chronic form of leishmaniasis in which there is a reduced response to Leishmania antigens and, therefore, it is observed in those cases with deficient cell-mediated immunity.1 The clinical picture in HIV-coinfected patients may be severe, with more than 200 lesions, or have a progressive course.2 In this context, clinical diagnostic difficulties can be seen in which the most important differentials are lepromatous leprosy and disseminated histoplasmosis, among others.3 Likewise, histopathological results may be inconclusive given the similarity to other entities in which certain findings (e.g. granulomas, parasitized macrophages) could lead to misdiagnosis.4,5

In our case, cutaneous lesions were similar to those of histoplasmosis and the positive Gomori structures within histiocytes seen in the first biopsy led to this initial diagnosis. In leishmaniasis, this latter and rare finding could be due to some kind of artifact from the histologic technique where amastigotes nuclei could capture silver nitrate (AgNO3) from Gomori stain.5 Beyond technical error, another possible explanation is the presence of structures resembling Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (MGB), reported in a few cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis.6,7 MGB, usually found in malakoplakia, are Gomori and Von Kossa positive. In Leishmania infection, these structures are Gomori positive but can be Von Kossa negative and have been hypothesized to correspond to bacterial contamination or phagosomes/phagolysosomes transformed by the parasite.6,7 Electron microscopy is useful to confirm MGB presence, but it was not performed in our case.

Although Histoplasma coinfection was plausible in our patient, it was ruled out considering the evidence of (1) a multidisciplinary approach (Dermatology, Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases, Pneumology, among others) in each hospitalization with relevant complementary studies did not find any pulmonary or cutaneous fungal involvement in serial images, nor in repeated samples for cytology, cultures, biopsies, and antigen detection. (2) The expected clinical picture in our context would have been that of disseminated histoplasmosis (DH), characterized by splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, adenopathy, pancytopenia, and pulmonary disease, in addition to skin lesions.4,5 None of these extracutaneous signs were seen at the follow-up. We should mention that DH-related skin signs are almost always a feature of disseminated disease in which a pulmonary focus is the initial point of dissemination to the skin.4

We propose these strategies to address the above-mentioned diagnostic difficulties: (1) consider the epidemiology since certain entities occur in specific areas; (2) clinical and histological clues specific to each disease allow to narrow down the diagnostic range (Tables 1 and 2)1–5; (3) in situations of complex or overlapping features, in addition to repeated biopsies obtained from different lesions together with examination of multiple serial sections and specific stains, it is it necessary to carry out additional diagnostic techniques such as PCR (Table 2).2,3,8 We also suggest using a combination of methods since some of them could have limited sensitivity3,8; (4) remember that in HIV patients, coinfections have the potential for atypical presentations, more than two organisms may coexist, and elevated relapse rates and poor response to conventional therapy have been reported.2,8

Comparative epidemiological and clinical findings in diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) and its differential diagnoses.

| Cause | Epidemiology (main distribution) | Clinical signs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCL | L. Mexicana, L. amazonensis, and ocassionally L. braziliensis | Central/South America | Multiple erythematous-to-violaceous macules, papules, nodules, and plaques especially on the face, extensor extremities, and buttocks; lesions are painless; diffuse cutaneous infiltration; ulceration not so common; mucosal lesions are possible; nerve involvement does not occur. |

| L. aethiopica, seldom by L. major | Africa | ||

| Lepromatous leprosy | Mycobacterium leprae | America, Africa, Asia | Multiple bilateral ill-marked papules, plaques, and nodules on the face ear lobes, extremities, and trunk; symmetric distribution; sometimes diffuse thickening; sensory loss in some lesions; nodules can ulcerate. |

| Mycobacterium lepromatosis | America, Asia | ||

| Disseminated histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Worldwide | Variable clinical presentation: molluscum contagiosum-like papules in most cases; nodules which converge to form warty lesions; plaques, pustules, abscesses, ulcers, cellulitis, purpuric lesions and panniculitis.The lung is the most common initial focus of infection. |

| DCS | Sporothrix schenkii | Worldwide | There are ≥3 lesions involving two anatomical sites; papules, pustules, plaques, ulcers, and gummata; it may progress into osteoarticular involvement. |

| Talaromycosis | Talaromyces marneffei | Southeast, South, and East Asia* | Mucocutaneous papules with central umbilication due to necrosis; predominantly on head and upper chest; also papules, pustules, nodules, subcutaneous abscesses or ulcers; multiple organ systems compromised. |

| Lobomycosis (verrucous or plaque-type) | Lacazia loboi | Central/South America* | Plaque and verrucous type: infiltrated plaques, nodules with a wart-like surface; usually in the lower limbs, followed by the ears, upper limbs, and head; ulceration in chronic disease; hypoesthesia/anesthesia. |

DCL: diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis; DCS: disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis.

Comparative histological and morphological findings in diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) and differential diagnoses in HIV patients.

| DCL | Disseminated histoplasmosis | DCS | Talaromycosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological features | Nodular dermatitis | Nodular dermatitis | Nodular dermatitis | Diffuse dermatitis |

| Absent or non-necrotic granulomas | Granulomas +/− in HIV patients | Suppurative or nonspecific granulomas | Focal necrosis, absent granulomas | |

| Numerous macrophages (MO): heavily parasitized | Yeast within cytoplasm of MO: surrounded by a clear halo | Yeast within phagocytic cells or extracellular | Yeast within cytoplasm of MO, also extracellular | |

| Few lymphocytes and plasma cells | Minimal inflammatory response (MIR) | MIR | Scattered MO | |

| Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PH) | Generally without PH | PH: +/− in HIV patients | PH: absent | |

| Morphology | Amastigote: 3–5μm round structure with bar shaped kinetoplast inside | Ovoid, encapsulated, and budding yeast, 2–4μm | Roundish spores, 4–6μmCigar bodies, 4–8μm longAsteroid bodies: – in HIV | Round/oval thin-walled yeast cell with transverse septum, 3–6μm |

| PAS and Gomori stains: negativeaGiemsa stain: intensely positive | PAS, Gomori: positiveGiemsa: positive | PAS, Gomori: positivecGiemsa: positivec | PAS, Gomori: positiveGiemsa: positive | |

| Additional diagnostic methods | Smear, culture | Culture, serum β-d-glucan | Culture: gold standard | Culture: gold standard |

| PCR | Urine H. capsulatum antigen:↑ levels in HIV patients | PCRd | Serum galactomannan | |

| Dermatoscopy | PCR | Sporotrichin skin testd: | PCR | |

| Montenegro skin test: – in DCLbAb testing: ↓ sensitivity in HIV | Ab testing: not good response in HIV patients | – in HIV patients | MALDI-TOF | |

DCL: diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis; DCS: disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; Ab: antibody; MALDI-TOF: matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight method.

Regarding the HIV–Leishmania interaction, studies from human cell cultures have shown that the upregulation of HIV replication in CD4+ T cells is driven by the lipophosphoglycan, the major surface protein of Leishmania.9 Furthermore, CD8+ T cells exhibit a low cytotoxic activity against infected macrophages, with the consequent unrestrained spread of Leishmania.10

In conclusion, this case illustrates the diagnostic drawbacks that could be found in DCL for which several solutions are suggested to address potential mistakes.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Luis Fernando Palma Escobar, Dr. María Janeth Vargas, and Dr. María Isabel González for their support in guiding and taking the histopathological photographs that illustrate this case report.