Chemotherapy can cause multiple dermatological alterations, including nail changes that significantly impact patients’ quality of life. This study aims to characterize the nail alterations induced by chemotherapy and assess their diagnosis through dermatoscopy.

MethodologyAn observational, prospective, and descriptive study that included 140 patients from the Fundación Instituto Valenciano de Oncología (FIVO). Both clinical and dermatoscopic nail alterations in the hands and feet were evaluated, associated with the different chemotherapy drugs administered. Analyzed variables included the type of nail alteration, the treatment cycle in which they appeared, and the observed dermatoscopic patterns.

ResultsThe prevalence of nail alterations was 45.7%, with chromonychia being the most frequent, followed by onycholysis. Lesions affected both hands and feet in 72.3% of cases. The most common chromonichias were erythronychia (36.4%) and leukonychia (9.3%). Monoclonal antibodies, tubulin binders, and platinum complexes were the drug groups most associated with these alterations. Onychomycosis was suspected in eight patients, confirmed in four cases through mycological cultures, where non-dermatophyte fungi were isolated.

ConclusionNail alterations induced by chemotherapy are common, affecting nearly half of patients. Dermatoscopy allowed the identification of alterations at early stages, which can facilitate the implementation of timely therapeutic strategies and improve patients’ quality of life.

Chemotherapy is essential in the treatment of many cancers. The increasing prevalence of cancer in the general population leads to greater use of chemotherapy and other antineoplastic therapies and, consequently, to a wide range of dermatologic toxicities that must be identified and treated to improve the patients’ quality of life.

Of note, cytotoxic drugs inhibit cell division. Therefore, while exerting their activity on tumor cells, they also act on healthy cells with a high mitotic index, such as those in the skin and its appendages, which may become affected.

It is important to detect chemotherapy-related toxicities at an early stage to implement therapeutic measures that reduce their severity and duration. In some cases, cutaneous toxicity requires dose reduction or even interruption of the drug, which may affect the patient's prognosis.1,2

Among the forms of cutaneous involvement, nail alterations may occur. Nail changes are primarily classified using the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE), which includes 5 nail changes (paronychia, nail loss, ridging, nail discoloration, and infection).3 However, this classification does not capture all nail alterations observed in patients undergoing cancer therapies, many of which may significantly impact quality of life.

Scientific literature predominantly consists of case reports, case series, and—less frequently—systematic and narrative reviews. As a result, the incidence rate of nail changes varies widely among studies, since it has not been investigated systematically. In addition, many studies focus on a particular group of drugs, such as taxanes, and include small samples.4–7

Furthermore, in most studies no standardized nail examination protocol is established to identify lesions, and in some cases there may be bias due to limited skill in detecting nail changes. Dermoscopy is a simple, noninvasive technique that allows visualization of small details not visible to the naked eye and contributes to better characterization and identification of nail alterations.

The aim of this study was to describe the main nail adverse effects of chemotherapy according to the drug used and the timing of onset in relation to the treatment cycle. Additionally, dermoscopic patterns were identified, as well as the location of the alterations (fingernails, toenails, or both).

MethodWe designed a descriptive, observational, prospective exploratory study. Patients on chemotherapy who were older than 18 years, between May 2023 and July 2023, were selected. The sampling method was non-probabilistic and consecutive, according to the order in which patients were attended at the Day Hospital and the Dermatology Service of XXX (institution withheld per journal requirements), on 2 fixed days per week. Due to the characteristics of the center, the study did not include children. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the XXX Research Ethics Committee (see previous note) (V1 03-13-2018).

All patients underwent clinical examination of the fingernails and toenails to define the main dependent variable of the study: the presence or absence of nail alteration. For patients with nail lesions, photographic documentation was performed, including clinical dorsal, lateral, and frontal views of the nail, as well as dermoscopic dorsal and frontal images of the affected nail plate.

A mycological culture was performed in patients with clinical signs suggestive of onychomycosis (onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, dystrophy, and/or chromonychia), after disinfecting the nail plate with 70% alcohol. To obtain the specimen, the distal nail edge was removed to collect material from the more active proximal area. The sample was collected with nail clippers and a scalpel by cutting the nail plate and scraping subungual hyperkeratosis. The specimen was placed in a properly labeled transparent container with patient identifiers.

The mycological study included fungal species identification and susceptibility testing. Sabouraud agar and Mycoline were used as culture media. Identification was performed using optical microscopy and MALDI-TOF. The mycological evaluation included assessment of macroscopic cultures, optical microscopy, fungal identification, and ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) sequencing, which enables identification by PCR amplification of the non-coding regions ITS-1 and ITS-2 of nuclear rDNA.

Independent variables included age (years), sex (male, female), tumor location (breast, ovary, cervix, endometrium, prostate, testis, bladder, kidney, pancreas, liver, esophagus, stomach, colon, lung, trachea, head and neck, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, melanoma), the treatment received for the neoplasm (categorized by mechanism of action as antimetabolites, antibiotics, alkylating agents, platinum compounds, tubulin-stabilizing agents, topoisomerase inhibitors, hormonal therapy), and the number of treatment cycles.

Nail lesions recorded included: pitting, hapalonychia, onychorrhexis, trachyonychia, Beau's lines, onychomadesis, onycholysis, onychoschizia, subungual hyperkeratosis, subungual exudate, anonychia, hapalonychia, chromonychia, onychocryptosis, pyogenic granuloma, dystrophy, onychomycosis (presence/absence). For cases of onychomycosis, the clinical type (distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, total dystrophic onychomycosis, white superficial onychomycosis, proximal onychomycosis, mixed onychomycosis) and etiologic agent (dermatophytes, yeasts, molds) were recorded. For all nail lesions, dermoscopic findings were assessed: longitudinal streaks, subungual hyperkeratosis, ruin appearance, irregular distal edge, onycholysis with regular or irregular borders, proximal erythematous border, salmon patch, splinter hemorrhages, subungual hemorrhage, red dots in the hyponychium, red dots on lateral folds, type of chromonychia (multicolor, melanonychia, leukonychia, erythronychia, xanthonychia, etc.), pattern of chromonychia (longitudinal, diffuse distal, diffuse proximal, distal linear, total diffuse), triangular sign, inverse triangular sign, aurora borealis sign, micro-Hutchinson, Hutchinson sign, pseudo-Hutchinson. Additionally, the timing of lesion onset (treatment cycle number) and associated symptoms, both prior to and during treatment, were documented.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0. Frequency analyses were performed for variables, and comparisons were made based on sex, patient age, the nail alteration identified, and the chemotherapy received.

ResultsA total of 140 patients were included, with a median age of 63 years (34–89); 47 (33.6%) were men and 93 (66.4%) women. The patients had 17 types of malignant neoplasms for which they were on chemotherapy; breast carcinoma was the most frequent (45 patients; 32.1%), followed by lung cancer (21 patients; 15%), and bladder and colon cancer (13 patients; 9.3% each) (Table 1).

Frequency of tumor location.

| Carcinoma | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 45 | 32.1 |

| Colon | 2 | 1.4 |

| Ovary | 7 | 5.0 |

| Bladder | 13 | 9.3 |

| Melanoma | 3 | 2.1 |

| Renal | 2 | 1.4 |

| Colon | 13 | 9.3 |

| Gastric | 4 | 2.9 |

| Pancreas | 9 | 6.4 |

| Endometrium | 1 | 0.7 |

| Cervix | 4 | 2.9 |

| Head and neck | 6 | 4.3 |

| Lung | 21 | 15.0 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 | 2.1 |

| Soft-tissue sarcoma | 2 | 1.4 |

| Esophagus | 1 | 0.7 |

| Prostate | 4 | 2.9 |

| Total | 140 | 100 |

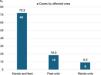

Nail alterations were identified in 64 patients (45.7%), mostly affecting both the hands and feet (46 patients; 72.3%) (Fig. 1). Lesions were more frequent in women (50 patients; 78.1%) than in men (14 patients; 21.8%). Patients were followed for a median of 65 days (interquartile range, 45–75 days).

There were 14 different types of nail alterations. The most frequent was chromonychia (62.9%), followed by onycholysis (25%) (Fig. 2). Among chromonychias, the most frequent were erythronychia (36.4%), leukonychia (9.3%; apparent in 7.9% and true in 1.4%), and purpura (7.9%).

Examples of nail changes in the study sample. Image 1 Globular-pattern erythronychia. Image 2. Erythronychia, Beau's line, and diffuse pigmentation. Image 3. Globular-pattern erythronychia. Image 4. Progression of globular erythema in a patient 2 months into chemotherapy: increased purplish area and onycholysis. Image 5. Red lunula. Image 6. Peri-lunular erythema. Image 7. Capillary dilatation in the nail bed. Image 8. Linear longitudinal erythema (longitudinal erythronychia). Image 9. Proximal diffuse nail-bed erythema. Image 10. Distal diffuse nail-bed erythema.

The pharmacologic groups most associated with nail alterations were monoclonal antibodies, followed by tubulin-stabilizing agents, platinum compounds, and antimetabolites.

Chromonychias were more strongly associated with monoclonal antibodies, whereas onycholysis was more commonly associated with tubulin-stabilizing agents and, to a lesser extent, with monoclonal antibodies (Table 2).

Frequency of the most common nail changes due to chemotherapy.

| Nail alteration | Number of patients | Percentage | Associated drug class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythronychia | 46 | 36.4% | Monoclonal antibodies (n=17)Tubulin-stabilizing agents (n=15)Antimetabolites (n=13)Platinum complexes (n=12)Antibiotics (n=4)Topoisomerase inhibitors (n=4)Alkylating agents (n=2) |

| Other chromonychias (leukonychia, melanonychia, purpura) | 35 | 23.6% Leukonychia9.3% Petechiae/purpura7.9% Melanonychia6.4% Xanthonychia 2.9% | Monoclonal antibodies (n=13)Tubulin-stabilizing agents (n=12)Platinum complexes (n=9)Antimetabolites (n=7)opoisomerase inhibitors (n=4)Corticosteroids (n=2)Antibiotics (n=1)Immunotherapy (n=1) |

| Onycholysis | 33 | 25% | Tubulin-stabilizing agents (n=14)Monoclonal antibodies (n=11)Antimetabolites (n=8)Platinum complexes (n=7)Antibiotics (n=3)Alkylating agents (n=2)Topoisomerase inhibitors (n=1)Corticosteroids (n=1) |

Tables 3–5 illustrate the clinical presentation and its relationship with the chemotherapy agents used for each major nail alteration observed.

Number of patients who developed erythronychia under different chemotherapy protocols.

| Chemotherapy protocol | Lesion onset | Number of patients (n=46) | Percentage | Type of erythronychia (dermoscopic pattern) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel (n=7)Bevacizumab (n=3)Carboplatin+Paclitaxel (n=3)Irinotecan (n=2)Capecitabine (n=2)Rituximab+Vincristine (n=2)Nivolumab (n=2)Trastuzumab+Paclitaxel (n=2)Cemiplimab (n=1)Oxaliplatin (n=2)Gemcitabine (n=1)Pembrolizumab (n=1)Pemetrexed (n=1)Enfortumab (n=1)Atezolizumab (n=1)Cisplatin (n=1)Calcium folinate+5-FU (n=1) | Cycle 1 and/or 3Cycles 1 and 6Cycle 1 and 2Cycle 3Cycle 2Cycle 3Cycles 2 and 10Cycle 1 and 2Cycle 3Cycle 2Cycle 1 and 4Cycle 3Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycle 5Cycle 2Cycle 2 | 35 | 76% | Diffuse erythema (Image 7) |

| Paclitaxel (n=2) | Cycle 2 | 2 | 4.3% | Peri-lunular or lunular erythema (Images 3 and 4) |

| Doxorubicin (n=1)Cisplatin (n=1) | Cycle 2Cycle 2 | 2 | 4.3% | Capillary dilatations (Image 5) |

| Trastuzumab (n=1)Paclitaxel (n=2)Calcium folinate+5-FU (n=1)Carboplatin (n=1) | Cycle 2Cycle 1Cycle 2Cycle 1 | 5 | 10.8% | Linear erythema (Image 6) |

| Cetuximab (n=1)Docetaxel (n=1) | Cycle 4Cycle 2 | 2 | 4.3% | Globular erythema (Images 1 and 2) |

Frequency of other chromonychias under different chemotherapy protocols.

| Chemotherapy protocol | Lesion onset | Patients with color changes (n=35) | Percentage | Type of discoloration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept+Irinotecan (n=1)Bevacizumab (n=2)Paclitaxel+Dexamethasone (n=2)Trastuzumab+Paclitaxel (n=2)Doxorubicin (n=1)Nivolumab (n=1) | Cycle 2Cycles 1 and 6Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycle 3 | 9 | 69.2% | Melanonychia |

| Paclitaxel (n=1)Cabazitaxel (n=1)Cetuximab+Irinotecan (n=2)Oxaliplatin+5-FU (n=1)Cisplatin (n=2)Carboplatin+Gemcitabine (n=1)Irinotecan+5-FU (n=2)Pembrolizumab (n=1) | Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycle 3Cycle 4Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycles 3 and 5 | 11 | 84.6% | Apparent leukonychia |

| Enfortumab (n=1)Nivolumab (n=1)Carboplatin+Paclitaxel (n=1) | Cycle 5Cycle 10Cycle 2 | 3 | 23% | True leukonychia |

| Paclitaxel (n=2)Doxorubicin (n=1)Cemiplimab (n=1)Trastuzumab (n=4)Rituximab+Vincristine (n=1)Cetuximab (n=3) | Cycles 1 and 2Cycle 2Cycle 3Cycle 2Cycle 3Cycle 4 | 12 | 92.3% | Diffuse pigmentation (purpura) |

Number of patients who developed onycholysis under different chemotherapy protocols.

| Chemotherapy protocol | Lesion onset | Patients with onycholysis (n=33) | Percentage | Type of onycholysis (dermoscopic pattern) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin (n=3)Carboplatin (n=3)Gemcitabine (n=1)Capecitabine (n=1)Bevacizumab (n=1)Paclitaxel (n=11)Polatuzumab+Rituximab (n=1)Trastuzumab (n=4) | Cycle 2Cycle 2Cycle 6Cycle 1Cycle 6Cycles 1 and 3Cycle 6Cycles 2 and 7 | 25 | 75.7% | Regular-border onycholysis |

| Paclitaxel (n=2)Cemiplimab (n=1)Cetuximab (n=1)Doxorubicin+Cyclophosphamide (n=2)Docetaxel (n=1)Oxaliplatin (n=1) | Cycle 1Cycle 3Cycle 4Cycles 1 and 2Cycle 2Cycle 6Cycle 1 | 8 | 24.3% | Irregular-border onycholysis |

Onychomycosis was suspected in 8 patients, and non-dermatophyte fungi were isolated in 4. Table 6 illustrates the clinical suspicion of onychomycosis, the dermoscopic pattern identified, the culture results, and the histologic findings from nail clipping.

Characteristics of patients with suspected onychomycosis (n=8).

| Chemotherapy protocol | Clinical suspicion of onychomycosis | Dermoscopy pattern | Culture result | Biopsy result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab | DLSO | Irregular-border onycholysis Xanthonychia Nail-bed erythema | Negative | Negative |

| Paclitaxel | DLSO | Irregular-border onycholysis Xanthonychia | Negative | Positive |

| Gemcitabine | DLSO | Regular-border onycholysis Subungual hyperkeratosis | Negative | Negative |

| Docetaxel | DLSO | Irregular-border onycholysis Nail-bed erythema | Fusarium spp. | Negative |

| Oxaliplatin+Bevacizumab | DLSO | Irregular-border onycholysis | Aspergillus terreus | Negative |

| Cisplatin+Pemetrexed | Endonyx | Xanthonychia | Aspergillus versicolor | Negative |

| Trastuzumab+Paclitaxel | DLSO | Regular-border, erythematous onycholysis Ruin sign | Negative | Positive |

| Rituximab+Vincristine | DLSO | Irregular-border onycholysis Ruin sign | Fusarium spp. | Negative |

DLSO: distal lateral subungual onychomycosis.

In this study, we describe the dermoscopic characteristics of nail changes in patients no cancer treatment.

The prevalence of nail alterations observed is similar to that reported in other studies. For example, Pavey et al. observed nail changes in 62.2% of the 53 patients examined,8 whereas Praveen Kumar et al. reported a prevalence of 33.3% in 50 patients.9

The most frequent finding was chromonychia, mainly erythronychia. The type of alteration differed depending on the mechanism of action of the chemotherapeutic agent used. In addition, fungal infection was identified in 4 patients.

Regarding nail discoloration, most studies refer to melanonychia, which has been identified in approximately 80% of patients8–11—findings that contrast with the 6.4% reported in the present study. In this case series, unlike previous ones, the most frequent lesion was erythronychia. Of note, unlike other studies, this work focused on dermoscopic findings, which may partly explain the identification of different types of changes, possibly because early erythematous changes—detectable with dermoscopy—may go unnoticed on routine clinical examination. Therefore, while Trivedi et al. identified erythronychia in 5.3% of patients, in the present series it was found in 36.4% of the cases. Those authors associated erythronychia with cisplatin. In contrast, in our study erythronychia was seen mainly with monoclonal antibodies, followed by tubulin-stabilizing agents, antimetabolites, and platinum complexes. It was identified in most cases after the 1st or 2nd treatment cycle, with different patterns (Table 3), progressing over subsequent cycles toward more violaceous, purplish, or bluish tones (Images 8 and 9), lesion enlargement, and in some cases, the appearance of onycholysis—possibly due to nail bed inflammation.

Furthermore, leukonychia was identified, a finding reported by Praveen Kumar et al. in 3.2% of patients, mainly in those on oxaliplatin.9 Trivedi et al. observed true leukonychia in 2.1% of patients on various chemotherapeutics.11 Chapman and Cohen suggest that no specific combination or group of chemotherapeutic agents is more frequently associated with acquired transverse leukonychia; however, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine may be the most widely involved drugs—a finding consistent with our observations.20

The findings also coincide with those reported by Praveen et al., who described diffuse pigmentation in 16% of patients on taxanes.9 These changes appeared in most cases after the 2nd treatment cycle. In our study, discoloration occurred more frequently with monoclonal antibodies, followed by tubulin-stabilizing agents and platinum complexes.

Falkson and Schulz, in a study of patients treated with 5-FU, observed melanonychia in 14 of 64 patients (21.8%).13 Five of the 13 patients from the study by Pratt and Shanks14 on doxorubicin developed melanonychia, which are findings consistent with our results. The exact etiology of melanonychia is unknown. It is thought to follow the stimulation of matrix melanocytes via an inflammatory response to chemotherapy, leading to melanocyte activation and melanin deposition in the nail plate. In addition, an increase in adrenocorticotropic hormone and melanocyte-stimulating hormone may enhance pigment production.15–19

In addition to chromonychias, other alterations such as onycholysis were observed. Most studies agree that taxanes (docetaxel and paclitaxel) are the chemotherapeutic agents most frequently associated with onycholysis, likely due to direct toxic effects. However, mild-to-moderate onycholysis may occur with other agents such as capecitabine, etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cetuximab, erlotinib, lapatinib, afatinib, dacomitinib, trametinib, cobimetinib, selumetinib, everolimus, temsirolimus, ibrutinib, and vandetanib.21–27

The pathophysiological mechanism of onycholysis in these patients is not clearly established. It may result from direct cytotoxic damage to epithelial cells of the nail bed, leading to epidermolysis and secondary loss of adhesion of the nail plate. Moreover, an antiangiogenic effect of taxanes has been proposed. Similarly, although some authors suggest a phototoxic mechanism for photo-onycholysis, this has not yet been confirmed.21,26,28,29 Based on our findings, nail bed erythema may represent an early sign of impending onycholysis, as seen in 22 of 46 patients with erythema. While distal onycholysis is the most common form in the general population, in patients on chemotherapy, nail bed inflammation may generate detachment patterns differing from those seen in individuals without cancer treatment. In our study, onycholysis was identified in 33 patients, representing 25% of all nail changes. The drug class most frequently associated was tubulin-stabilizing agents (paclitaxel and docetaxel), which is consistent with the literature, followed by monoclonal antibodies, antimetabolites, and platinum complexes.

Finally, possible onychomycosis was suspected in 8 patients (7 were suspected to have distal lateral subungual onychomycosis based on clinical and dermoscopic findings and 1, endonyx onychomycosis). Mycological culture confirmed onychomycosis in 4 patients (confirmed with repeat culture), all involving non-dermatophyte fungi. Although these organisms may represent contaminants, we cannot rule out that separation between the nail plate and bed may facilitate colonization by pathogenic microorganisms contributing to onychomycosis. It seems reasonable to recommend nail care measures to patients at the beginning of cancer treatment to minimize the occurrence of onycholysis and prevent secondary onychomycosis.

In conclusion, nearly half of patients on chemotherapy exhibit nail alterations—diverse in nature but predominantly erythronychia and onycholysis—most commonly involving both fingernails and toenails. The increasing use of new cytotoxic agents highlights the need to recognize all nail alterations and provide appropriate management to relieve local symptoms. Dermoscopy helps identify lesions at an earlier stage and enables earlier intervention, which may be especially relevant for infection-prevention strategies in the setting of onycholysis. Proper patient counseling supports treatment adherence and may help achieve the optimal duration of chemotherapy, thereby improving response rates and avoiding treatment interruptions.

Uncited reference12.