Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an option for the treatment of actinic keratosis, Bowen disease, and certain types of basal cell carcinoma. It is also used to treat various other types of skin condition, including inflammatory and infectious disorders. The main disadvantages of PDT are the time it takes to administer (both for the patient and for health professionals) and the pain associated with treatment. Daylight-mediated PDT has recently been reported to be an alternative to the conventional approach. Several studies have shown it to be similar in efficacy to and better tolerated than classic PDT for the treatment of mild to moderate actinic keratosis. Nevertheless, most of these studies are from northern Europe, and no data have been reported from southern Europe. The present article reviews the main studies published to date, presents the treatment protocol, and summarizes our experience with a group of treated patients.

La terapia fotodinámica (TFD) constituye una alternativa terapéutica para las queratosis actínicas, la enfermedad de Bowen y determinados carcinomas basocelulares. Se utiliza además para el tratamiento de otras enfermedades cutáneas de diversa naturaleza, incluyendo enfermedades inflamatorias e infecciosas. Los principales inconvenientes de la TDF convencional son el tiempo que consume su realización (al paciente y al personal sanitario) y el dolor que produce. Recientemente se ha descrito la TFD con luz de día (TFDLD) como alternativa al procedimiento convencional. En diversos estudios se ha mostrado similar en eficacia y mejor tolerada que la TFD clásica en el tratamiento de queratosis actínicas leves-moderadas. No obstante, la mayoría de los estudios realizados proceden del norte de Europa, y no existen por ahora resultados en países de la latitud de España. El presente artículo revisa los principales estudios publicados hasta el momento, expone el protocolo de utilización y resume nuestra experiencia en un grupo de pacientes tratados.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has become established as a treatment for actinic keratosis (AK), Bowen disease, and certain types of basal cell carcinoma over the past decade because it is highly effective for these dermatoses and gives excellent cosmetic results.1–5 PDT is currently included in clinical guidelines for treating nonmelanoma skin cancers1,4,6–10 and is considered the first line of therapy for multiple AKs and field cancerization.4,11–15 The range of indications for PDT has broadened in recent years and now encompasses infectious conditions,16–19 inflammatory dermatoses,8,20–22 adnexal diseases,23–25 skin tumors,17,26–28 and photoaging.8,29–31 The potential value of PDT as a preventive treatment in transplant patients or those with conditions that are difficult to manage, such as Gorlin syndrome, has also been recognized.32–36 However, the application of conventional PDT10 is a laborious, time-consuming process for health professionals and patients alike and requires special equipment that takes up space in a clinic. The classic protocol10 specifies that the photosensitizer should be applied and kept covered (occlusion) for a certain period—usually 4to 6hours or more for 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or 3 hours for the 5-ALA methylester, or methyl aminolevulinate (MAL). After incubation, the area is exposed to an appropriate source of light. The most common combinations of light sources and doses used in Europe are the Aktilite (Galderma, Lausanne, Switzerland) at 37J/cm2 for approximately 8minutes and the Waldmann PDT 1200L (Waldmann GmbH & Co, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany) at 75to 100J/cm2 for approximately 20minutes. PDT is not free of adverse effects.37–44 The most common one, and the most limiting, is pain during illumination, which must sometimes be interrupted; analgesia or local or regional anesthesia may be required.45,46

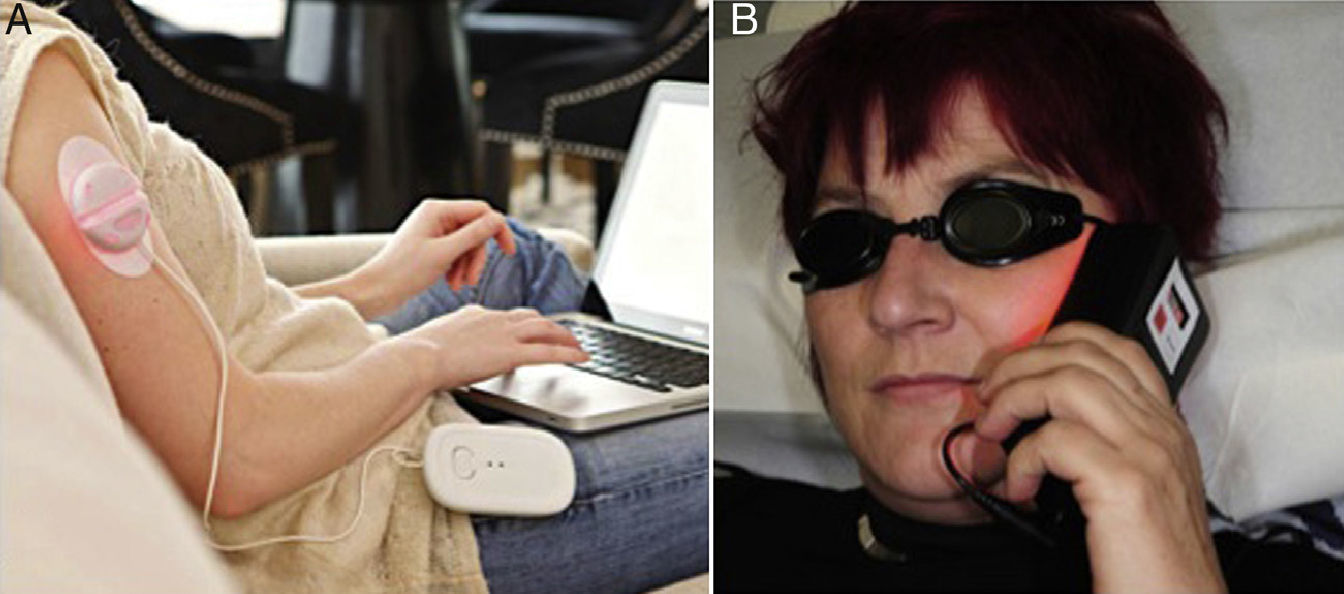

With the use of portable light sources (Fig. 1) to optimize the procedure and facilitate outpatient treatment,47–49 the concept of ambulatory PDT has emerged.50 This modality is costly, however, and is only useful for treating small lesions. The most important methodological simplification introduced in recent years has been the therapeutic use of daylight.51,52

Ambulatory photodynamic therapy using portable light sources.50 A, Ambulight (Ambicare Health Ltd, St Andrews, Fife, UK) (http://www.ambicarehealth.com/ambulight-pdt/). This device uses an adhesive patch with a red light emitting diode (LED)—peak emission 640±25 nm—that delivers a dose of 75J/cm2. Light intensity is low (7mW/cm2) and exposure lasts for 3h.49 Image used with the permission of Ambicare Health Ltd. B, AK-derm (Sellas GmbH, Ennepetal, Germany). High-intensity LED (70–80mW/cm2) that emits 37J/cm2 in 8min; peak emission is 630nm±5nm. Image used with permission of Dr Helger Stege (Klinikum Lippe, Detmold, Germany).

Daylight PDT uses a combination of direct and reflected sunlight outdoors.53 Using the sun as a light source has encouraged more widespread use of PDT, has lowered costs considerably, and has enhanced adherence.

Clinical Trials and Other Published StudiesThe available publications are summarized in Table 1. Strasswimmer and Grande54 suggested in 2006 that daylight could activate a photodynamic reaction, a claim that others disputed.55 Batchelor and colleagues51 were the first to report the effective use of daylight PDT to treat multiple scalp AKs in a 90-year-old patient who showed good tolerance of the session. The most important work on this modality has been published since 2008 by the group of Wiegell and colleagues at Hospital Bispebjerg in Denmark. Most of their studies have enrolled patients with AK (Table 1). In a pilot study with 29 patients they initially demonstrated that daylight-mediated PDT was as effective against AKs as red-light PDT using a light-emitting diode as the source; daylight therapy was also much less painful.52 The authors suggested that progressive, slower activation of protoporphyrin IX [PpIX] by small amounts of the photosensitizer (rather than rapid activation of large amounts of PpIX in the target tissue after several hours of incubation) might reduce the pain associated with treatment; they also suggested that since red and blue light fall within the spectrum of daylight, this source might be effective in therapy and also facilitate treatment. The use of natural light, therefore, could theoretically be useful and enhance therapy. In a later study they compared the efficacy of daylight-mediated PDT using MAL at concentrations of 16% and 8%, observing no differences in response rates, grades of erythema or pain between patients using the different concentrations.56 The authors suggested that MAL concentrations lower than the usual one of 16% could be effective. In 2011 they published the results of the first multicenter trial of daylight PDT in patients with nonhyperkeratotic AKs, finding that outcomes after exposures of 1.5and 2.5hours were similar.57 The authors recommended a 2-hour exposure time. The 2 later studies confirmed the earlier findings that daylight PDT is effective in nonhyperkeratotic AK. However, this modality proved less effective on hyperkeratotic AK lesions.58

Characteristics of the Principal Studies of Daylight-Mediated PDT Treatment of AK.

| Wiegell et al.52 | Wiegell et al.56 | Wiegell et al.57 | Wiegell et al.58 | Braathen59 | Shumack et al.a | |

| Journal | BJD | BJD | BJD | BJD | ADV | Unpublished |

| Year of publication | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 | 2012 | 2012 |

| Study design | Randomized, controlled, single blind | Randomized, double blind | Randomized, multicenter | Randomized, multicenter | Retrospective case series | Multicenter, randomized, blinded, within-patient controlled |

| Country | Denmark | Denmark | DenmarkNorwaySweden | DenmarkNorwaySweden | Switzerland | Australia |

| No. of participating centers | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 7 |

| Objective | To compare conventional red-light PDT to daylight PDT without occlusion | To compare response rates and adverse events in daylight PDT with 8% or 16% MAL | To compare the efficacy of daylight PDT with MAL after 1.5or 2.5h of exposure | To assess the efficacy of PDT with MAL in AK of different levels of severity. | To assess the feasibility of, adherence to, and satisfaction with daylight PDT in private practice | To assess the noninferiority of daylight PDT and the maximum pain caused |

| Treatment season | June–Sept 2006 | June–Sept 2007 | June–Oct 2008 | June–Oct 2008 | April–Sept 2011 | Mar–May 2012 |

| Follow-up, mo | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| No. of treatment sessions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No. of cases | 29 | 30 | 120 | 145 | 18 | 100 |

| Age, yb | 73 (63–90) | 71 (51–94) | 72 (47–95) | 72 (47–95) | 72 (60–85) | 66.9 (42–90) |

| Sex, M/F | 23/6 | 26/4 | 96/24 | 117/28 | 12/6 | 75/35 |

| Grade of AK | I, II | I, II, III | I | II, III | I, II | I, II |

| Principal location | Face, scalp | Face, scalp | Face, scalp | Face, scalp | Face, scalp | Face, scalp |

| Surface area treated | 80cm2 | 80cm2 | At least 25cm2 | At least 25cm2 | 1–10AKs | 8×18cm |

| Sunscreen | None | P20 (Riemann & Co A/S, Hilleroed, Denmark) | P20 | P20 | Louis Widmer F15gel | SPF 30 |

| Time between application of sunscreen and photosensitizer | NA | 15min | 15min | 15min | 5–15min | NS |

| Photosensitizing agent | MAL 16% | MAL 16%, MAL 8% | MAL 16% | MAL16% | MAL 16% | MAL 16% |

| Amount of photosensitizer or layer thickness | 1g | 1g | “Thick layer” | 1-mm layer | Layer of 0.5–1 mm | NS |

| Photosensitizer incubation | 30min on the daylight PDT side; 3h on the conventional PDT side | Wait of 0–120min before sun exposure | ≤ 30min | ≤ 30min | 30min | ≤ 30min |

| Occlusion after photosensitizer application | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Time of day for exposure | NS | 11–18h | 8–18:30h | NS | 11–16h | 9–18h |

| Exposure duration recommended | 2.5h | Rest of the day | 1.5h vs 2.5h | 1.5h vs 2.5h | 90min on a sunny day; 120min on a partly cloudy or cloudy day | 2h |

| Light dose | Effective total exposure dose, 34.2J/cm2 (range, 11.7–65.9J/cm2) | Mean effective dose, 30.1J/cm2 (range, 1.2–69.8J/cm2) | Mean effective dose, 1.5h, 8.6J/cm2; in 2.5h,10.2J/cm2 | 100 patients received >3.5J/cm2; 37 patients received <3.5J/cm2 | NS | NS |

| Weather conditions | Sunny or partly cloudy | 3 patients exposed on cloudy or rainy days | Sunny or partly cloudy (83%); rainy or cloudy (17%) | Sunny or partly cloudy; rainy or cloudy | >12°C, on days without rain | Sunny/partly cloudy |

| Results at 3 mo c | 79% reduction of AK in the treated area | 76.9% reduction in number of AKs (MAL 16%); 79.5% (MAL 8%) | Mean response rates: after 1.5h, 77.2%; after 2.5h, 74.6% | Mean response rates: 75.9% in AK I;61.2% in AKII;49.1% in AKIII | Mean response rate, 77% (range, 0%–100%) | 82% reduction in AKs |

| Pain (scale 0–10) | Mean maximum pain, 2 (1.9) | MAL 16%, 3.7 (2.4);MAL 8%, 3.6 (2.4) | 0–1, 92%;4–7, 7.5%;8–10, 0.8% | NS | 1 patient, 5 out of 10; others, 0 | Mean, 0.8 |

| Other adverse effects | Erythema, crusting | Erythema, crusting | Erythema, 74%; pustules, 29% | NS | Erythema, edema, crusting | NS |

Abbreviations: ADV, Actas Dermo-sifiliográficas; AK, actinic keratosis; BJD, British Journal of Dermatology; F, female; M, male; MAL, methyl aminolevulinate; Mar, March; NA, not applicable; NS, not specified; Oct, October; PDT, photodynamic therapy; Sept, September.

Braathen59 reported similar results for daylight PDT used to treat facial and scalp AKs in a series of 18 patients in a private practice setting.

The results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial in Australia were recently presented by Shumack and colleagues at the Euro-PDT meeting (the annual conference of the European Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology) in Madrid from May 31 to June 1, 2013. This study showed that daylight PDT was not inferior to conventional PDT and that it was better tolerated and preferred by both patients and the investigators. This study confirmed the findings of earlier ones done in Nordic settings52,56–58 and was the first undertaken in a country with a climate that is very different from that of northern Europe. The same conference brought together reports of other smaller trials of daylight PDT. In one study, Grinblat and colleagues used 1 to 3 sessions to treat 14 patients with grade I or II AKs. The setting was Brazil and exposure was performed between 9am and 11:30am for a period of 60to 90minutes. Most patients experienced improvement. In the Netherlands, Venema used daylight-mediated PDT to treat 2 patients with actinic cheilitis, observing good clinical and cosmetic results. Tolerance was excellent. Le Pillouer-Prost presented the findings of a French study of 17 patients with grade I to III AKs. Five of the patients had been pretreated with fractionated carbon dioxide laser therapy. After 1 or 2 sessions of daylight PDT, depending on lesion thickness, most AKs in the pretreated group had resolved. Lesions had also cleared in 10 of the 12 patients who had not been pretreated. Finally, Enk, described using this modality in 14 patients with nonulcerated cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel. The patients were exposed to daylight in the hospital's garden for 2.5hours immediately after application of MAL. The cure rate was 86% after an average of 5 weekly sessions. Scarring was minimal and the procedure was painless.

The main conclusions of the most important studies and a discussion of the details of the different approaches to this form of PDT can be found in a Euro-PDT consensus paper.53

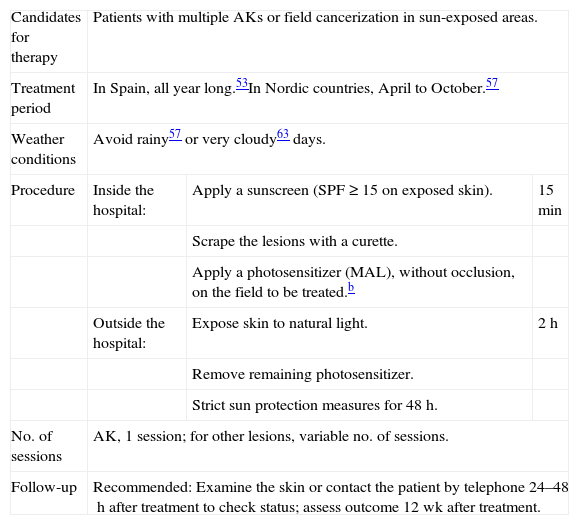

Treatment ProtocolThe only treatment protocol currently available for daylight-mediated PDT was proposed by Wiegell and colleagues57 and is summarized in Table 2. Considering that this PDT modality is at present off-label, the patient must be adequately informed about the procedure, its adverse effects, and efficacy. Written informed consent must be obtained. In order to assess the final outcome, baseline photographs of the area to be treated should be taken, and it may be useful to count and map the lesions in the field. Pretreatment with topical keratolytic agents may be advisable in some cases. Once the patient is in the treatment room, a sunscreen is applied to all exposed areas of the skin, even the area targeted for treatment. The sunscreen should provide a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 20 and not contain physical, or inorganic, filters. Approximately 15minutes after sunscreen application, the lesions should be scraped with a curette. A layer of MAL cream approximately 1mm thick is then spread on the field to be treated. Occlusion is not needed. The patient should be outdoors and start exposing the area to daylight within half an hour of MAL application. The recommended duration of exposure is 2 hours, after which the remaining photosensitizer is removed and the skin is cleaned. The treated field should be protected from sunlight the rest of the day. Sun protection measures should be continued for at least the next 48hours.

Protocol for Daylight-Mediated PDT. a

| Candidates for therapy | Patients with multiple AKs or field cancerization in sun-exposed areas. | ||

| Treatment period | In Spain, all year long.53In Nordic countries, April to October.57 | ||

| Weather conditions | Avoid rainy57 or very cloudy63 days. | ||

| Procedure | Inside the hospital: | Apply a sunscreen (SPF ≥ 15 on exposed skin). | 15min |

| Scrape the lesions with a curette. | |||

| Apply a photosensitizer (MAL), without occlusion, on the field to be treated.b | |||

| Outside the hospital: | Expose skin to natural light. | 2h | |

| Remove remaining photosensitizer. | |||

| Strict sun protection measures for 48h. | |||

| No. of sessions | AK, 1 session; for other lesions, variable no. of sessions. | ||

| Follow-up | Recommended: Examine the skin or contact the patient by telephone 24–48h after treatment to check status; assess outcome 12 wk after treatment. | ||

Abbreviations: AK, actinic keratosis; MAL, methyl aminolevulinate; PDT, photodynamic therapy; SPF, sun protection factor.

The ideal thickness remains to be established. The prescribing information recommends a layer 1mm thick. However Wulf and colleagues have reported using a thinner layer without loss of efficacy (Dr. H. C. Wulf, personal communication at the thirteenth annual conference of the European Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology [Euro-PDT], in Madrid, May 31 to June 1, 2013).

This modality is mainly appropriate for cooperative patients who have multiple AKs (preferably grade I or II) or field cancerization in sun-exposed areas and who find conventional PDT to be very painful. Daylight PDT will probably gradually come to be used for skin diseases other than AK.

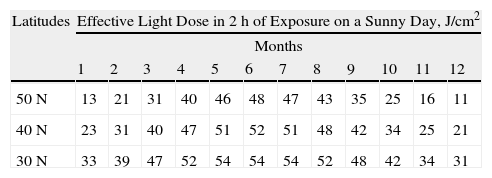

What Light Dose Is Needed for Effective Activation of PpIX?The amount of irradiation received in 2hours of direct sunlight at midday varies greatly according to geographic location, weather conditions, and season.60 The threshold dose for PpIX activation (at which daylight PDT will be effective for destroying AKs) varies in studies published to date (8, 6, and 3.5J/cm2).53,57,58,60 Until the effective dose is established more precisely, a threshold of 8J/cm2 is currently considered adequate to ensure that therapy will be effective.60 Using meteorological models and dosimeters installed at a number of geographic locations it has been possible to establish the effective light doses for activating PpIX in 2hours of exposure at midday on the fifteenth day of each month at different latitudes.53 Accordingly, it would be possible to reach daylight doses over 8J/cm2 in Spain in any month, depending on weather conditions; this treatment could therefore be completed within the 2-hour time frame all year round53 (Table 3).

Light Dose Received in 2h of Exposure at Midday in the Middle of Each Month at the Range of Latitudes in Which Spain Is Included. a

| Latitudes | Effective Light Dose in 2h of Exposure on a Sunny Day, J/cm2 | |||||||||||

| Months | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 50N | 13 | 21 | 31 | 40 | 46 | 48 | 47 | 43 | 35 | 25 | 16 | 11 |

| 40N | 23 | 31 | 40 | 47 | 51 | 52 | 51 | 48 | 42 | 34 | 25 | 21 |

| 30N | 33 | 39 | 47 | 52 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 52 | 48 | 42 | 34 | 31 |

Spain extends from about the 30°N (Punta de Tarifa) to 43°47¿N (Estaca de Bares). Columns show months by number. Months are expressed as numbers; 1 indicates January, 2 indicates February, etc. Adapted from Wiegell et al.53

Exposure should take place outside in the middle of the day and last 2hours.57 However, Grinblat and colleagues (unpublished, Euro-PDT meeting) used shorter exposure times of 60to 90minutes and observed results that were similar to those of multicenter studies.57,58 Considering at the PpIX activation range corresponds to visible light, which passes through glass, Hospital Molhom in Vejle, Denmark, uses a glass structure to protect patients from certain weather conditions and increase comfort during exposure (Fig. 2).

What Period of the Year Is Most Appropriate for Daylight-Mediated PDT?It seems to be possible to provide treatment at midday all year round in Spain unless there is a thick cloud cover.53 Temperature may be a limiting factor, however, as studies in vitro and in mice suggest that low temperatures reduce PpIX production.60–62 Low temperatures also make it difficult for the patient to stay outside during exposure. A temperature range of 10°C to 35°C for daylight PDT has been recommended,60 but there is room for variation according to patient characteristics and exposure location. To date, no studies have demonstrated that there are differences in treatment efficacy outside this temperature range.

Wiegel and colleagues60 a linear association between the UV index and the light dose that activates PpIX production during exposure at midday (11am to 1pm) for 2hours; when the UV index exceeds 3, patients receive over 8J/cm2 in this period. Weather conditions also play a part, as the effective daylight dose can decrease 25% on partly cloudy days, 50% on cloudy days, and 75% on rainy days.53,60 The exposure time required on such days has not been determined, and although some authors recommend not scheduling this modality of PDT on rainy57 or very overcast63 days, it would be useful to more precisely determine the required conditions for delivering the minimum effective light dose.

Why Is a Sunscreen Needed and What Sunscreen Is Appropriate for PDT?The recommendation to use a sunscreen aims mainly to prevent the adverse effects of UV radiation during exposure to sunlight. Sunscreens used to date have varied in their SPF levels, ranging from SPF 15,59 to SPF 20,53,57 to SPF 30 and SPF 50 (by Grinblat and colleagues and by Le Pillouer-Prost, respectively; unpublished reports, Euro-PDT meeting). Similar outcomes have been observed with all of these sunscreens. It is important to use one that does not contain mineral filters, which might block the visible light necessary for PpIX activation in addition to UV radiation. A list of sunscreens appropriate for use in daylight-mediated PDT has been provided by the Spanish company Laboratorios Galderma SA. It includes the following products: from Laboratorios Uriage, Bariesun cream, SPF 30/50; from Laboratorios Ducray, Melascreen solar emulsion, SPF 50; from Laboratorios Eucerin, Sun Spray transparent, SPF 30/50; from Laboratorios Bioderma, AKN Mat SPF 30/UV-A 13, MAX cream, SPF 50+/UV-A 38 and AKN Spray SPF 30/UV-A13; and from Laboratorios ISDIN, a transparent SPF 30 gel-cream.

What Limitations Affect Daylight-Mediated PDT?Daylight-mediated PDT is of great benefit for certain patients and for dermatologists who have neither the time nor the infrastructure for conventional PDT. However, there are certain limitations, such as the difficulty of scheduling sessions because of unpredictable weather and the constraints imposed by climate conditions in some geographic areas. At northern European latitudes, solar radiation is insufficient and temperatures are too low to accommodate sessions during some seasons (autumn and winter). Conditions in countries like Spain are different. It is still unclear whether very intense exposure for 2hours at our latitudes might be risky for our patients, but the Australian clinical trial described above has shown that daylight-mediated PDT is effective and safe in countries with strong solar radiation. Another problematic issue is the lack of rigorous control over therapy during the ambulatory outdoor period of the procedure, as the patient is the one who monitors illumination. To date, we still do not know the impact these possible differences might have on the effectiveness of therapy. In addition, daylight PDT seems to be less effective than conventional PDT for grade III AKs, and for the moment we lack sufficient evidence to support daylight-mediated PDT for other types of skin lesions. We expect to have new data in the future, however.

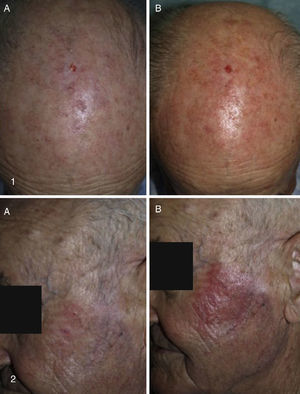

Our Hospital Departments’ ExperienceThe dermatology services under the Integrated Management System in Vigo (at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo [CHUVI] and Hospital San Jorge in Huesca [HSJ]) have used daylight-mediated PDT in 35 (CHUVI) and 9 (HSJ) patients with multiple grade I, II or III AKs, or field cancerization. Lesions were located on the face and/or scalp (CHUVI and HSJ) or legs (HSJ). Most patients were treated in a single session, but some underwent 2 sessions (HSJ). The results (Fig. 3) were similar to those achieved with conventional PDT for grade I or II AKs but inferior for grade III AKs. The main adverse effects were inflammation and crusting in the treated area. These effects were less intense, however, than those usually seen after conventional PDT (Fig. 4). Patients treated in the CHUVI reported less pain (scores, 0–3 on a scale of 0 to 10) after daylight mediated PDT than after conventional PDT (scores, 6–10) Most patients who had previously undergone conventional PDT expressed a clear preference for the daylight-mediated modality. The use of this approach allowed us to schedule treatment more quickly and accommodate all of them. Daylight was particularly useful for treating CHUVI patients who lived outside the city, and this choice also considerably reduced the amount of time the CHUVI staff spent preparing and supervising therapy.

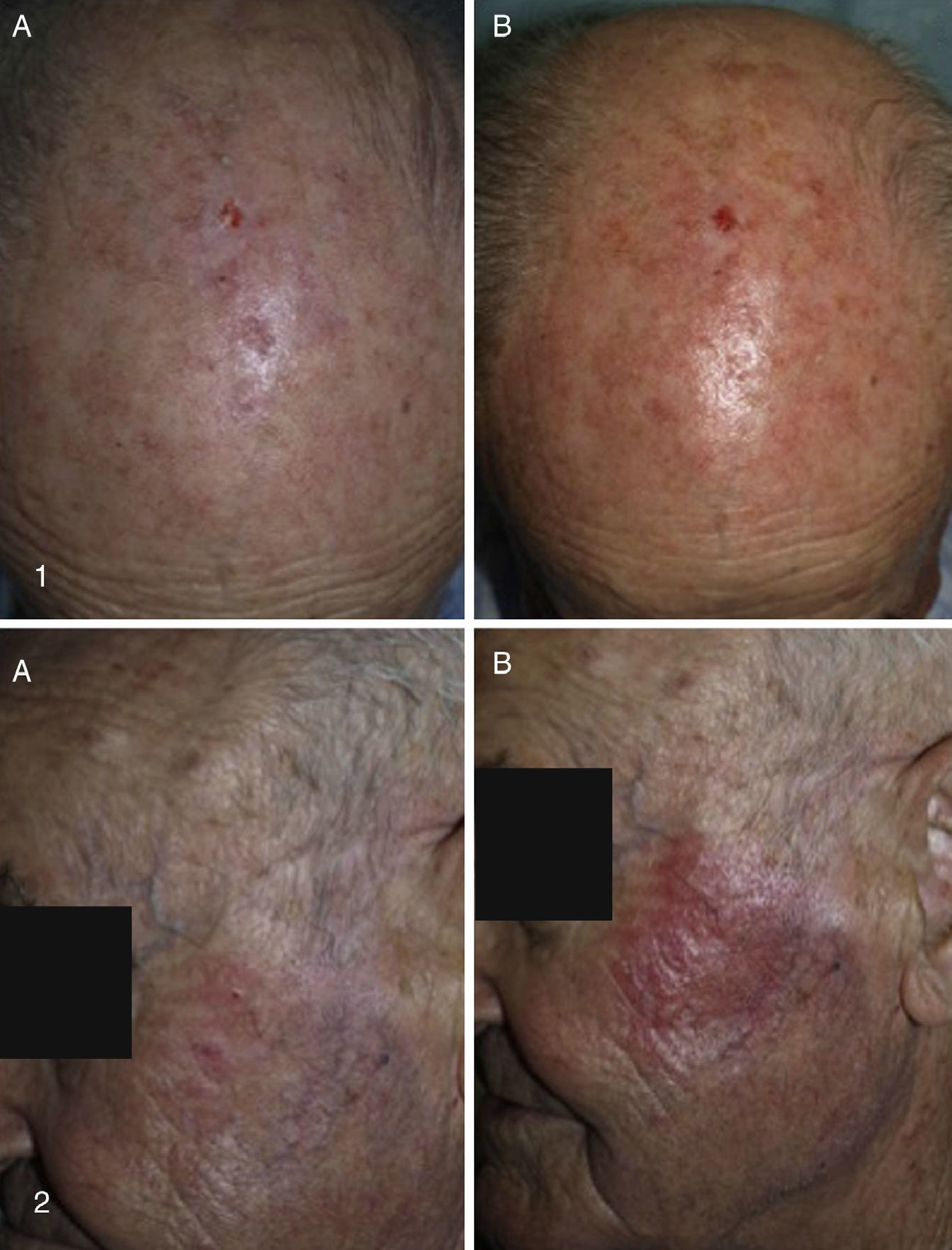

Results of treating multiple AKs with daylight photodynamic therapy (PDT). Photographs in the left column show lesions before treatment. Photographs on the right show the same lesions after treatment. Follow-up images in cases 1to 3 (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, of the Integrated Management System in Vigo) were taken 3mo after a single PDT session. Follow-up images in cases 4and 5 (Hospital San Jorge, Huesca) were taken 8mo after 1 PDT session and 4mo after 2 PDT sessions, respectively.

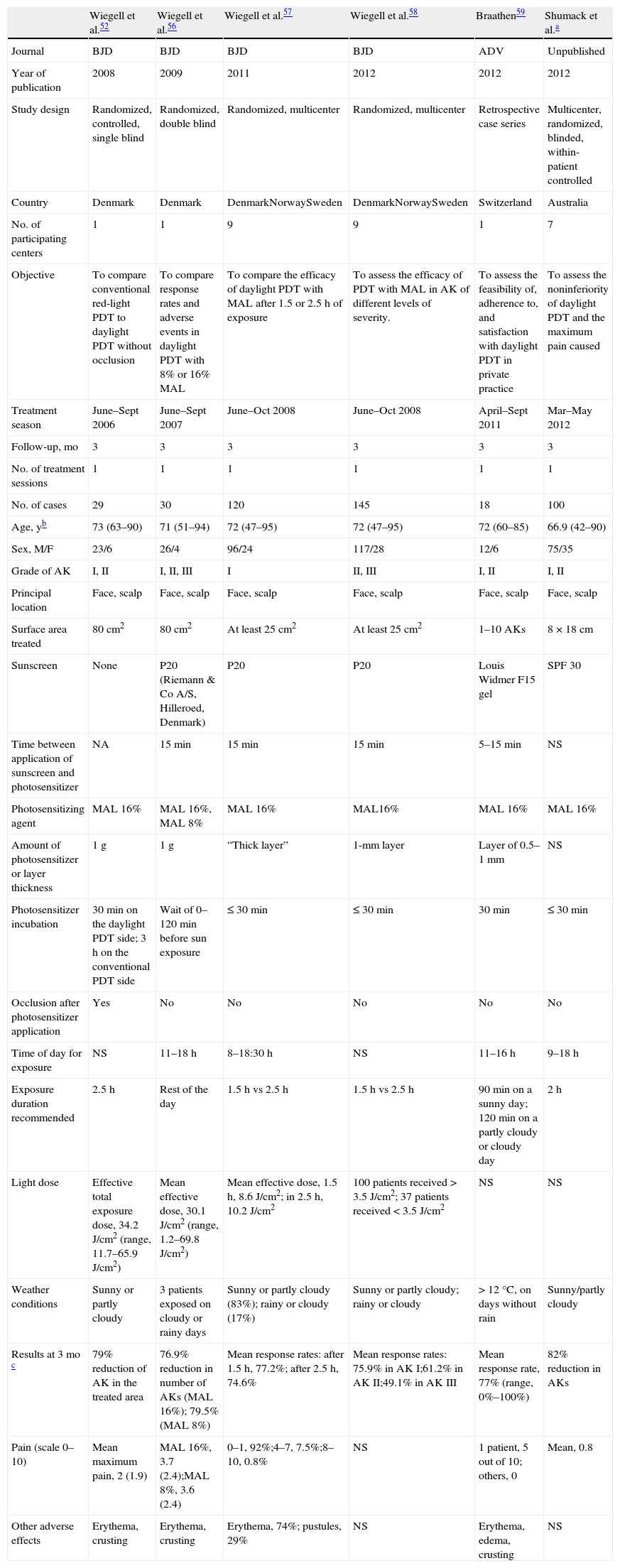

A, Baseline appearance of treated actinic keratosis lesions. B, Erythema and inflammation 3h after treatment. The lesions in the upper photographs (1A and B) were treated with daylight photodynamic therapy (PDT). The lesions in the lower photographs (2A and B) were treated with conventional PDT. Photographs from Hospital San Jorge.

Daylight-mediated PDT is an important new modality in dermatology. It has proven to be as effective as conventional PDT for treating AK and is a technically simpler method. Tolerance of therapy has improved considerably with the use of natural light. Both patients and specialists often express a preference for daylight PDT because the ambulatory procedure is simple and easy to organize. However, important disadvantages are that it is difficult to schedule because of weather conditions at certain times of the year and because light exposure is difficult to control. Over time, this modality will probably begin to have applications in the treatment of skin conditions other than AK, as has occurred with conventional PDT in recent years.

Although a protocol for daylight-mediated PDT has been proposed57 and an international consensus paper has been published,53 many aspects remain speculative to a certain degree and need to be defined in the short-term so treatment can be fully standardized. Some of these aspects are the obligatory use of a sunscreen, the most appropriate SPF for this clinical use, the ideal amount and concentration of photosensitizer, whether occlusion is necessary, the effective daylight dose required for PpIX activation, the exact exposure time required at different times of day and in specific weather conditions, the real effect of ambient temperature on efficacy, and the possible use of photosensitizers other than MAL.

According to information available at this time, Spain has an ideal climate for providing daylight PDT all year round. Existing international treatment protocols are currently based on conditions in Nordic countries. In order to adapt them to other settings, a clinical trial is currently under way in several European countries, including Spain, and the results are expected to be available soon. The findings will help us establish optimal procedures for applying daylight PDT in Spain.

Conflicts of InterestDr Lidia Pérez has attended Spanish and international meetings about PDT at the invitation of Laboratorios Galderma SA; she was a speaker at the first meeting organized by that company on PDT in Galicia. Dr Yolanda Gilaberte has received consulting fees from Laboratorios Galderma SA; she has received fees for speaking for that company at various conferences.

We express thanks to Dr Stephen Schumack (St. George Dermatology and Skin Cancer Centre; Kogarah, Australia) for information about the Australian multicenter study on daylight-mediated PDT.

Thanks to Dr Beni Grinblat for information on results of his group's study of daylight-mediated PDT in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Thanks to Dr Ann Le Pillouer-Prost for sending information about the study of daylight-mediated PDT in Marseille, France.

Thanks to Dr Helger Stege (Klinikum Lippe, Detmold, Germany) for providing information about the AK-Derm device and a photograph of it.

Thanks to Dr Peter Bjerring (Hospital Molhom, Vejle, Denmark) for his kind permission to use a photograph of the greenhouse used by his department.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Gilaberte Y. Terapia fotodinámica con luz de día en España: ventajas y limitaciones. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:663–674.