Moringa is a plant native to the southern Himalayas that belongs to the Moringaceae family. The most common species is Moringa oleifera. It is widely used in traditional medicine in developing countries owing to its empirical nutritional, antioxidant, and therapeutic properties. Although its active principles and its effects remain unknown, the moringa market in developed countries is booming.1,2 We present a case of a rarely described adverse effect: cutaneous toxicity due to moringa.

A 57-year-old woman with a personal history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and fibromyalgia was referred to the emergency department for a generalized pruritic rash that had appeared 3 days earlier and was accompanied by mild respiratory distress and edema of the tongue.

Physical examination revealed a morbilliform rash on the face, trunk, and upper limbs that consisted of confluent erythematous papules that disappeared with diascopy and was interspersed with areas of healthy skin. There were no vesicles or blisters and the mucous membranes were spared (Figs. 1 and 2).

During the interview, the patient denied having consumed any new medication or food, but reported that for 2 weeks she had been taking moringa in powder form in order to lose weight, adding unspecified amounts to salads and taking daily infusions.

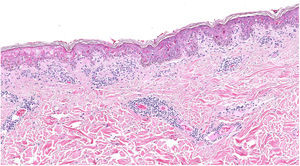

A biopsy showed dotted and confluent necrotic keratinocytes with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3).

Based on the suspected diagnosis of cutaneous toxicity due to moringa, use of moringa powder was discontinued and the patient was prescribed symptomatic treatment with antihistamines and a topical corticosteroid, which resulted in progressive resolution of the condition over the following 10 days.

Moringa, like any medicinal plant, can cause harm due to the direct pharmacological effects of some of its components, interactions with commonly used drugs, or the presence of unknown contaminants. The exact mechanism of action of moringa is unknown and most studies have exclusively investigated its anti-inflammatory properties, although its effects in our patient were precisely the opposite.

The reported adverse effects of moringa include alterations in liver and kidney function, miscarriage, alterations in hematologic parameters, diarrhea, insomnia, and lithiasis.3 No frequent cutaneous adverse effects have been reported.

Several studies of M oleifera have been published in recent years, mainly in rodents, and have shown that these harmful effects appear to increase in correlation with dose and duration of consumption. However, little effort has been made to standardize the moringa extracts studied, and it is therefore difficult to compare and contrast results between studies.4

No adverse effects were reported in a human study conducted with whole leaf powder at a single dose of 50 g or in another study in which participants received a dose of 8 g per day for 40 days.4 However, higher concentrations of toxic substances have been detected in the seeds, root, and bark of the plant.3

One case of urticaria was described in an article published in the journal of the Spanish Society of Allergology and Immunology. The authors described a 54-year-old man who presented with urticaria after taking a food supplement consisting of powdered moringa leaves.5 An article recently published by the Sri Lankan medical association described Stevens–Johnson syndrome in a 53-year-old man who had consumed moringa leaves.6 Rash and urticaria are the most frequently reported immediate adverse reactions associated with herbal medicines.2

The few published studies of moringa have demonstrated that it contains the potentially toxic agents moringin and moringinin, plant alkaloids that are structurally very similar to ephedrine.7 Both ephedrine and pseudoephedrine exert adverse cutaneous effects, which include eruption, fixed drug eruption, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, and erythroderma.8,9

Descriptions of lesion histology are absent from most of these reports and, if included, tend to consist of variable, nonspecific changes. Reported findings include hydropic changes in the basement membrane and perivascular infiltrate, but not necrosis as intense as that observed in our patient’s biopsy, the results of which were compatible with Stevens–Johnson syndrome.10

These types of plants are classified as dietary foods or supplements, and therefore do not require evidence of quality, efficacy, or safety prior to commercialization. Due to the large number of components that a single plant can contain, evaluation of efficacy and safety is much more complex than for conventional drugs.

We wish to highlight the importance of monitoring the consumption and adverse effects of M oleifera, given the growing market for this plant in Europe.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sagrera A, Montenegro T, Borrego L. Toxicodermia por Moringa oleifera. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:953–954.