Skin complications arising from tattoos include contact dermatitis, photodermatosis, lichenoid reactions, granulomas (foreign body, sarcoid), and infection.1,2 Small outbreaks of skin infections due to Mycobacterium chelonae in contaminated tattoo ink have recently been reported.

Patient 1Patient 1 was a 33-year-old man who had had a tattoo placed on his right leg 4 years previously. Three months before consulting, he had the shield outlined in black and a gray flame added. Asymptomatic lesions appeared 2 weeks later and were treated unsuccessfully with topical corticosteroids and antibiotics. The patient was then referred to the dermatology department.

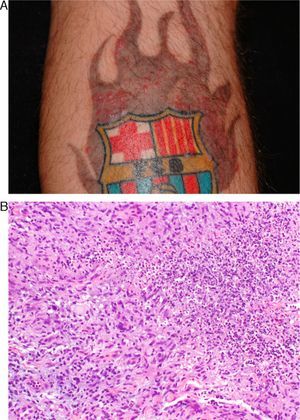

Physical examination of the gray flame revealed several papulopustules measuring 1mm to 4mm in diameter (Fig. 1A). The border drawn in black ink the same day was not affected. Analysis of a biopsy specimen revealed granulomas with abscess formation (Fig. 1B); Kinyoun staining was negative. M chelonae grew in culture 15 days later. The chest x-ray was normal, and laboratory tests (including serology for HIV and hepatitis) were negative. The patient was treated empirically with clarithromycin (500mg/12h) for 3 months. The lesions disappeared.

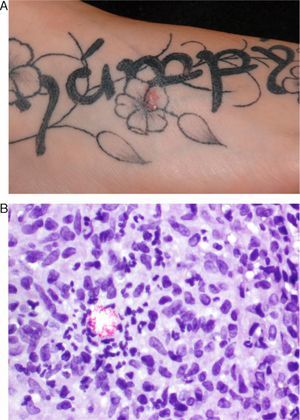

Patient 2Patient 2 was a 25-year-old woman who had had a black and grey tattoo placed on the dorsum of the foot 5 months previously by the same tattoo artist. Five days later, an asymptomatic lesion appeared on the gray areas. The lesion had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antibiotics and corticosteroids. Physical examination revealed an erythematous plaque measuring 1cm in diameter that was soft to palpation with occasional pustules on its surface (Fig. 2A). Analysis of a biopsy specimen revealed granulomas with abscess formation; Kinyoun staining showed a small accumulation of acid-alcohol-fast bacteria (Fig. 2B), but culture was negative. The patient was treated with clarithromycin (500mg/12h), although the drug was withdrawn in less than a month because of digestive tract intolerance. As the lesion had disappeared, no further treatment was administered.

DiscussionM chelonae is a fast-growing saprophytic mycobacterium that is found in tap water and water tanks and can contaminate surgical material. Skin infections have been reported in surgery, acupuncture, mesotherapy, and tattooing. In the case of tattoos, the infections affect the gray areas, as nonsterile water is added to the black ink.

The first case of a tattoo infected by mycobacteria was reported in 2003. Diagnosis was based on Ziehl-Neelsen staining and positive results in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. De Quatrebarbes et al4 later reported the first epidemic of M chelonae in tattoos. Twenty men presented with a rash in the gray area of their tattoos 7 to 10 days after having them performed by the same artist. Culture was positive for M chelonae in 13 patients.4 Goldman et al5 subsequently included these patients in a letter reporting on 48 patients who were tattooed by 2 different artists in Le Havre, France. M chelonae was found in 2 bottles of diluted black ink. New cases have since been reported in France,6 Australia,7 and the United States.8,9 Rodríguez-Blanco et al10 recently reported 5 cases in La Coruña, Spain; 3 were culture-positive and 2 PCR-positive. Table 1 summarizes the cases published to date.

Cases of Skin Infection by Mycobacterium chelonae in Tattoos.

| Author/Year/Country | No. of Cases | Time to Appearance | Time to Diagnosis | Histology | Mycobacterial Staining | Culture | Treatment |

| Wolf and Wolf/20033/Israel | 1 | ND | 3 mo | Granulomatous dermatitis | + | PCR+atypical mycobacteria | None |

| Goldman et al./20105/Francea | 48 | 3-35 d | 2 mo (mean) | 50% granulomas | NDb | 13+/30 | Clarithromycin in 41 patients+tobramycin (10 patients) |

| Kluger et al./20086/France | 8 | 10-21 d | 2-5 mo | Inflammatory dermatitis and granulomatous reaction | – (+ in ink) | – | Minocycline (1 mo) |

| Preda et al./20097/Australia | 1 | 2 mo | Inflammatory and granulomatous dermatitis | ND | + | Clarithromycin+moxifloxacin4 mo | |

| Drage et al./20108/United States | 6 | 1-2 wk | Mean 17.6 (range, 10-22) wk | Inflammatory dermatitis (3 cases)Granulomatous dermatitis (3 cases) | – | 3+/6 | Clarithromycin 6 mo |

| Rodríguez-Blanco et al./201010/Spain | 5 | 3-30 d | ND | Inflammatory dermatitis (3 cases)Granulomatous dermatitis (2 cases) | – | 3 + | Clarithromycin 3-5 mo (2 patients) |

| Kappel and Cotliar/20119/United States | 1 | 45 d | 2 wk | Inflammatory and granulomatous dermatitis | ND | + | Clarithromycin and levofloxacin, 6 mo |

| Present report, 2011 | 2 | 5-15 d | 3-5 mo | Granulomatous dermatitis | 1+ | 1+ | Clarithromycin, 1-3 mo |

Abbreviation: ND, no data.

All the cases involved the appearance of papulopustules in the gray areas of the tattoo 1 to 2 weeks after placement. No systemic involvement was recorded. The diagnostic delay (1-5 mo) is noteworthy, as the patients were initially diagnosed with an allergic reaction or bacterial infection and were treated with topical antibiotics, corticosteroids, or both. No standard treatment has been defined, although the most widely used agent is clarithromycin, which, according to Drage et al,8 should be prescribed for at least 6 months; however, digestive tract intolerance makes this difficult.10 Some clinicians have combined clarithromycin with quinolones9; others have found a 1-month course of minocycline to be successful.6

The tattoo artist claimed to have used disposable material with each patient. The gray color was obtained by mixing black ink with rose water bought at the pharmacy. We assume that this water or the mixture became contaminated and was thus the cause of the infection, although we were unable to verify this, as all the material had been disposed of.

As tattooing is increasingly common, we wish to stress the importance of using disposable material and sterile products in order to avoid this type of infection. Furthermore, black ink should be mixed with sterile saline or water when the tattoo is being placed in order to avoid subsequent contamination; the mixture should not be stored.

Clinicians should suspect this infection and be able to recognize it, since staining is usually negative and culture positive in only 40% to 60% of cases. New PCR techniques can help to confirm the diagnosis.

Curcó N, et al. Infección cutánea por Mycobacterium chelonae en un tatuaje. Presentación de 2 casos y revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:842-5.