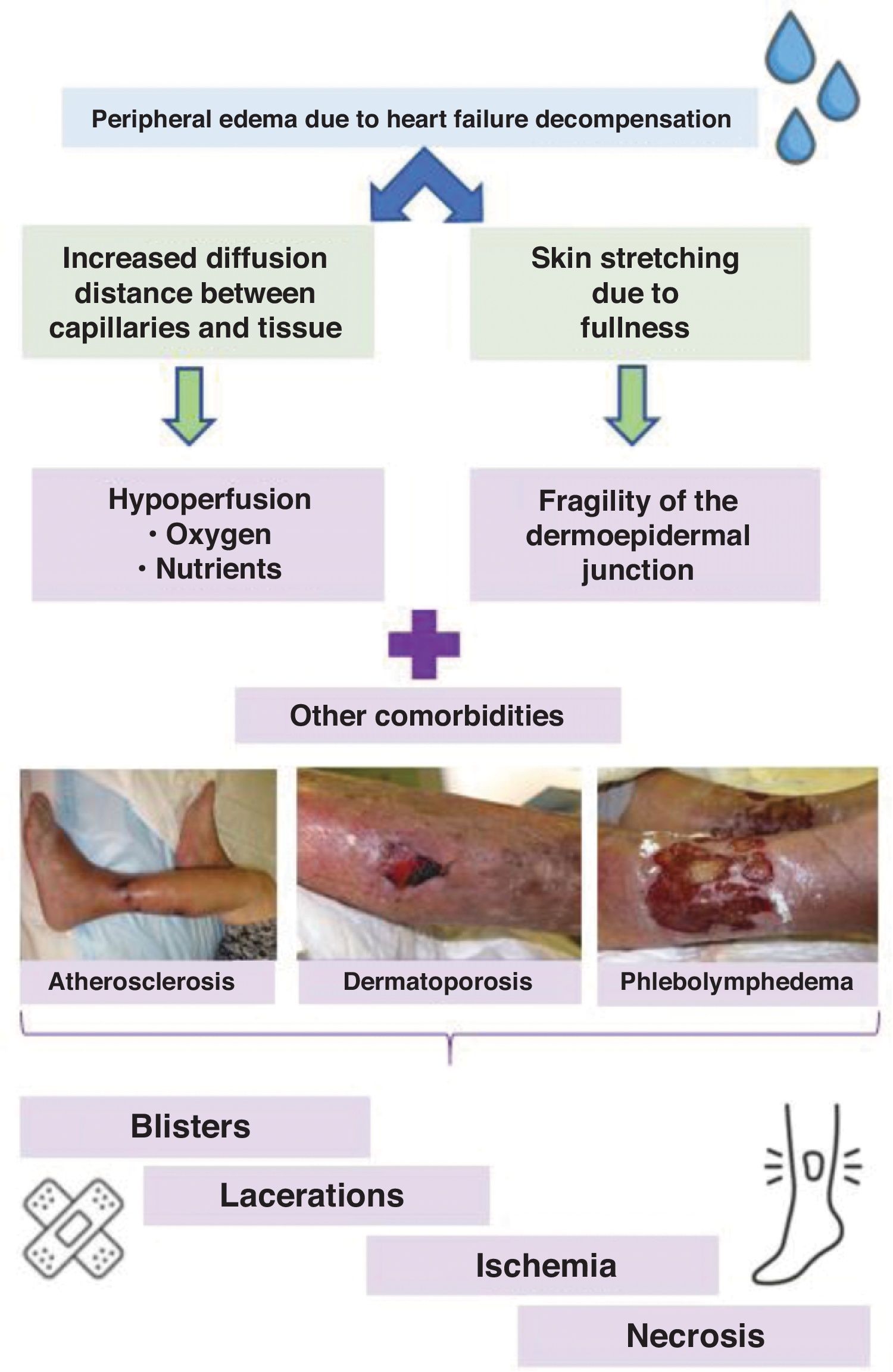

In Spain, heart failure is the most common reason for hospitalization in elderly patients. Its key clinical signs include dyspnea, fatigue, and peripheral edema. The rapid onset of lower extremity edema often leads to the development or worsening of wounds of varying complexity. This occurs due to an increased diffusion distance between the capillary network and the dermoepidermal tissue caused by the edema, impairing tissue perfusion. Additionally, compensatory mechanisms due to tissue hypoperfusion activate the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, resulting in greater sodium and water retention1 and further clinical worsening of the edema.

In patients with pre-existing conditions that reduce tissue perfusion—atherosclerosis or phlebolymphedema—peripheral edema in decompensated heart failure can trigger Martorell ulcers (an atherosclerosis-related ulcer spectrum) or worsen previous predominantly venous ulcers.2 Furthermore, the skin stretching increases, weakening the dermoepidermal junction. In the context of old age-related dermatoporosis, there is an increased tendency for the formation and complication of skin tears. Fig. 1 illustrates the pathophysiology and comorbidities associated with wounds due to increased diffusion distance.

Current clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend focusing heart failure decompensation treatment on peripheral decongestion, as it is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms in these patients.3

Historically, compression therapy was contraindicated in heart failure. However, the only absolute contraindications now are severe peripheral artery disease and advanced heart failure classified as NYHA (New York Heart Association) IV—characterized by an inability to perform physical activity without discomfort, with symptoms present even at rest.4 In less severe cases, gradual increases in compression pressure have shown only brief phases of increased cardiac load and can significantly reduce peripheral edema, although the available scientific literature on compression therapy in heart failure is fairly limited.1

In daily dermatological practice, wounds triggered or worsened by a cardiac decompensation episode are a common reason for consultation. Compression therapy has proven beneficial, reducing the length of stay, diuretic drug needs, and improving quality of life when using devices with Velcro closures.3,4 In our opinion, this therapy is underused, likely due to fear or lack of knowledge.

Compression therapy must always be tailored to the patient's functional status, ideally using high-rigidity devices (e.g., Velcro-closure devices, short-stretch bandages, or multi-component systems) alongside anti-edema measures such as elevating the legs above heart level while at rest.5

In this context, considering the increased diffusion distance due to heart failure decompensation—a common yet sometimes neglected condition—is essential as a factor that exacerbates poor wound healing in the legs. Dermatologists should advocate for and support the use of compression therapy as an adjuvant therapy to diuretics in reducing the peripheral edema characteristic of this disease. In fact, compression therapy has proven useful in reducing edema resistant to classical diuretics.6

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We wish to thank Dr. Elena Conde for her warmth and dedication to numerous trainees, her exemplary patient care, and her inspiration to a generation of dermatologists in the management of geriatric dermatological patients.