Both the functions and equipment of dermatologists have increased over the past few years, some examples being cosmetic dermatology, artificial intelligence, tele-dermatology, and social media, which added to the pharmaceutical industry and cosmetic selling has become a source of bioethical conflicts. The objective of this narrative review is to identify the bioethical conflicts of everyday dermatology practice and highlight the proposed solutions. Therefore, we conducted searches across PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases. Also, the main Spanish and American deontological codes of physicians and dermatologists have been revised. The authors recommend declaring all conflicts of interest while respecting the patients’ autonomy, confidentiality, and privacy. Cosmetic dermatology, cosmetic selling, artificial intelligence, tele-dermatology, and social media are feasible as long as the same standards of conventional dermatology are applied. Nonetheless, the deontological codes associated with these innovations need to be refurbished.

Las funciones y herramientas del dermatólogo se han incrementado en los últimos años; algunos ejemplos son la dermatología estética, la inteligencia artificial, la teledermatología y el uso de redes sociales. Estos junto con la industria farmacéutica o la cosmética son origen de problemas bioéticos. El objetivo de la presente revisión narrativa es identificar los problemas bioéticos de la práctica dermatológica y señalar las soluciones que se han propuesto. Para ello, se han realizado búsquedas en PubMed, Web of Science y Scopus y evaluado los principales códigos deontológicos españoles y americanos de médicos y dermatólogos. Los autores recomiendan declarar el conflicto de interés, respetar la autonomía, confidencialidad y privacidad del paciente. La dermatología estética, venta de cosméticos, inteligencia artificial, teledermatología y uso de redes sociales pueden ser adecuados si se cumplen con los mismos estándares que en la práctica habitual. Es necesario la actualización de los códigos deontológicos a las novedades.

The specialty of Dermatology and Venereology is closely related to the origin, development, and consolidation of modern Bioethics. The most representative example is the “Tuskegee Experiment,” which involved the intentional infection of African American men with syphilis to study the natural progression of the disease.1–4 This experiment was leaked to the press in the 1970s, resulting in the development of the Belmont Report and the Principles of Bioethics, 2 works that establish the 4 principles that should govern human research: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.1–4

Similarly, controversial experiments were conducted by dermatologist Albert M. Kligman in Holmesburg Prison (Philadelphia, United States) from 1951 through 1974. The researcher is attributed with the phrase: “All I saw before me were acres of skin, it was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.” He exposed the skin of these prisoners to detergents, radioactive compounds, and hallucinogens, intentional infections with bacteria and viruses, and testing of tretinoin cream, which left these African American men with lifelong scars and burns. Undoubtedly, although he contributed to modern dermatology by coining the term photoaging with tretinoin cream and his studies on contact dermatitis, he did so at the expense of human dignity.5–7

Dermatology has become more sophisticated since the beginning of the new millennium, evidenced by the increased relevance of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures. Therefore, the dermatologist has become not only the doctor of skin diseases but also the protector and guardian of healthy skin.8 Additionally, dermatology has grown new branches, such as teledermatology, artificial intelligence (AI), and the use of social media (SM).9–11 All these advances, along with collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry, photography, management of minorities, and the sale of cosmetics12–14 are sources of ethical problems and dilemmas in the routine clinical practice.

Medical associations are not insensitive to these problems. The Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) is a century-old scientific society dedicated to promoting education and maintaining the professionalism of Spanish dermatologists. In 2022, AEDV issued its own code of ethics to ensure excellence in Spanish dermatology.15 Similarly, international organizations, such as the American Medical Association (AMA), have their own code of ethics.16 Recently, the Spanish Medical Association (OMC) has published the new mandatory code of ethics for Spanish doctors.17

JustificationGiven the importance and interest involved with bioethics on the national and international arena, it is essential to conduct a narrative review to elucidate the main bioethical issues currently faced by dermatology. The present review will focus on aspects such as the management of vulnerable groups, clinical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, aesthetic dermatology, bioethics training, dermatological photography, the pharmaceutical industry, AI, SM, and teledermatology to improve the management of bioethical conflicts in everyday practice.

ObjectivesThe objectives of this narrative review are:

- 1.

To identify in the scientific literature the bioethical problems associated with dermatologic care for vulnerable groups, clinical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, aesthetic dermatology, bioethics training, dermatological photography, the pharmaceutical industry, AI, SM, and teledermatology.

- 2.

To highlight recommendations for addressing these issues.

- 3.

To establish whether medical and dermatologic codes of ethics address these issues.

Research questions were:

- 1.

Which bioethical issues can arise in regular dermatologic or aesthetic dermatologic consultations?

- 2.

What solutions do the authors of scientific articles propose?

- 3.

Do the codes of ethics for doctors and dermatologists address these issues?

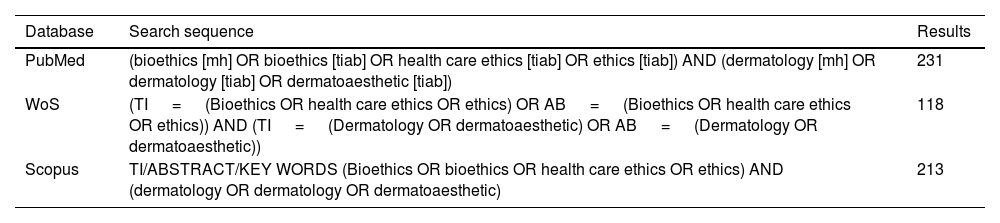

Searches were conducted across PubMed (MEDLINE), Web Of Science (WOS), and Scopus from March 1st to March 5th, 2023. Results were limited to the period that goes from 2000 through 2023. The terms, boolean operators, and fields used are shown in Table 1.

Search sequences.

| Database | Search sequence | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (bioethics [mh] OR bioethics [tiab] OR health care ethics [tiab] OR ethics [tiab]) AND (dermatology [mh] OR dermatology [tiab] OR dermatoaesthetic [tiab]) | 231 |

| WoS | (TI = (Bioethics OR health care ethics OR ethics) OR AB = (Bioethics OR health care ethics OR ethics)) AND (TI = (Dermatology OR dermatoaesthetic) OR AB = (Dermatology OR dermatoaesthetic)) | 118 |

| Scopus | TI/ABSTRACT/KEY WORDS (Bioethics OR bioethics OR health care ethics OR ethics) AND (dermatology OR dermatology OR dermatoaesthetic) | 213 |

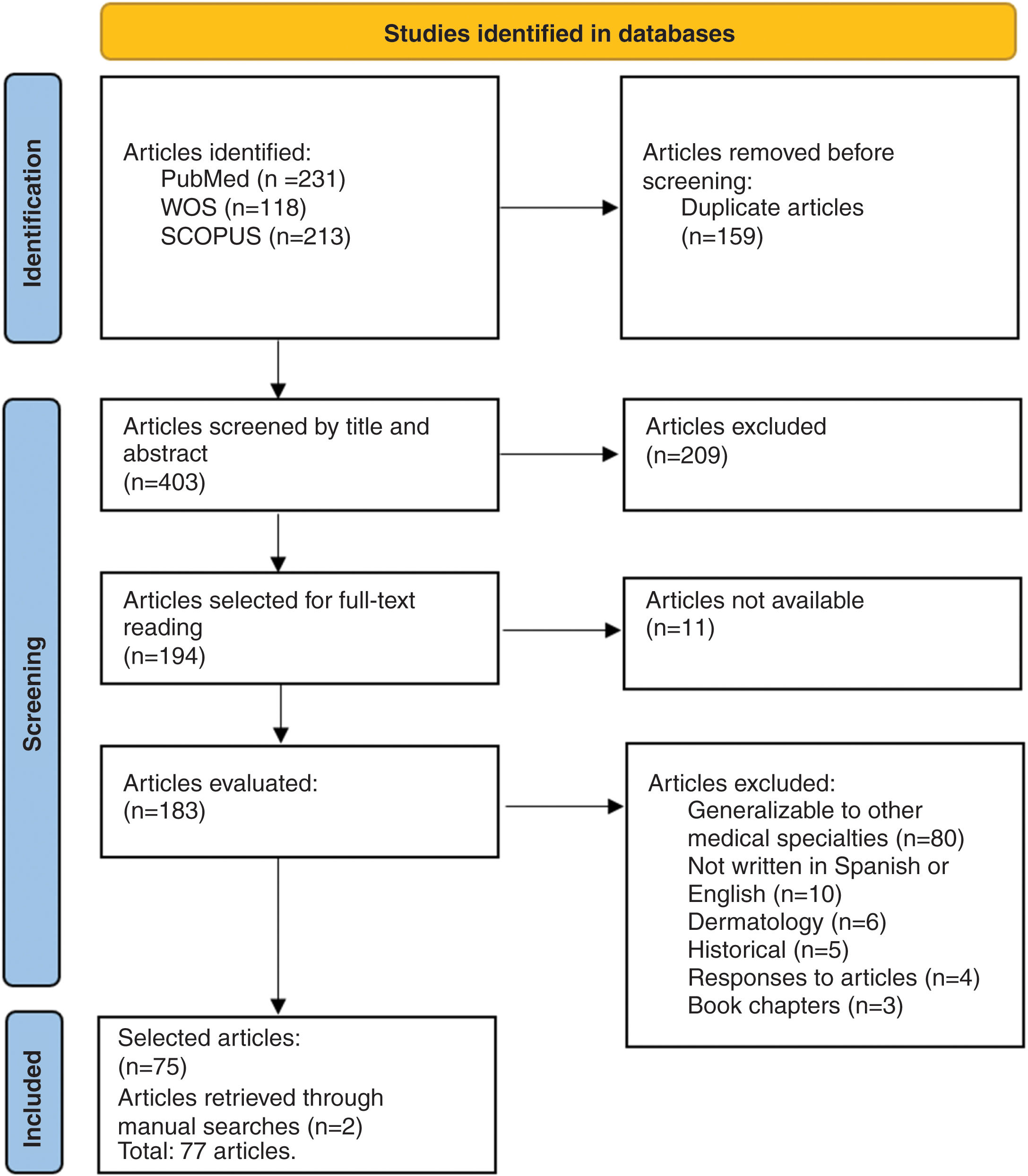

The selection of articles was conducted in full compliance with the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews” (PRISMA-ScR) methodology.18 Inclusion criteria were scientific opinion articles, letters to the editor, reviews, and case reports on bioethics. Clinical trials and protocols were not included as they focused on obtaining informed consent (IC) for participant involvement in research.

Exclusion criteria were full text not available, articles not written in Spanish or English, responses to articles, book chapters, historical articles, those addressing broadly applicable issues to all specialties such as participation in clinical trials, and dermatopathology articles. Grey literature was also reviewed, particularly the Spanish Medical Code of Ethics (CDM-E)17 and that of the American Medical Association (CDM-AMA),16 the AEDV Ethical and Good Governance Code (CE-AEDV),15 and the Standards of Professionalism and Ethics for dermatologists of the American Academy of Dermatology (EPE-AAD).19

Selected articlesThe search found a total of 562 articles, 159 of which were duplicates, leaving 403 articles total. After evaluating title and abstract, 194 were selected for full reading, and, eventually, a total of 77 articles were selected to become part of this narrative review (Fig. 1).

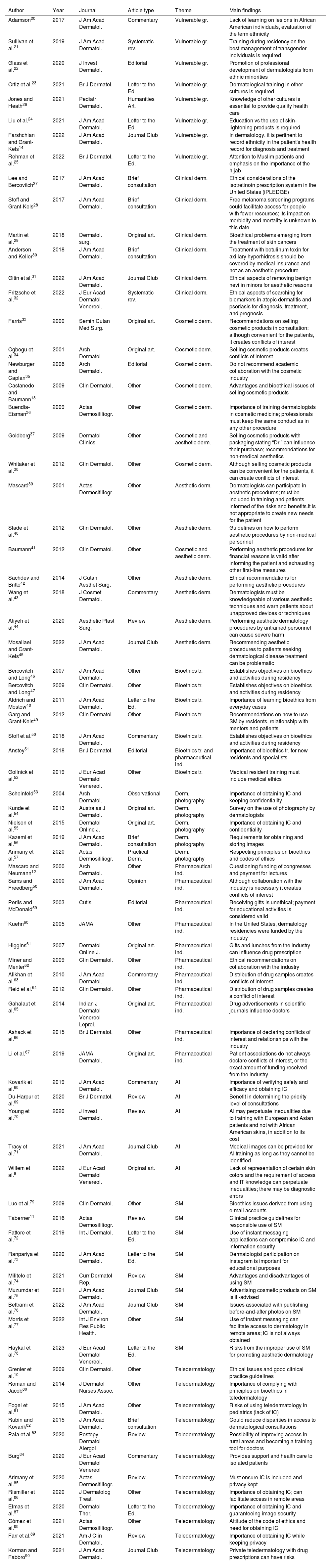

Categorization of resultsBioethical issues were categorized as vulnerable groups (issues related to minority ethnic groups or LGBTQ+), clinical dermatology (related to common skin diseases and conditions), cosmetic dermatology (related to cosmetic products), aesthetic dermatology (related to the practice of aesthetic techniques such as botox, fillers, lasers, and hair transplants), Bioethics training (training for residents and specialists), dermatological photography (issues related to taking photographs of patients), the pharmaceutical industry (problems arising from industry collaboration), AI (related to the use of AI systems in dermatology), SM (related to the use of e-mails, instant messaging services, and SM), and teledermatology (issues related to the use of teledermatology).

ResultsA total of 77 articles were eventually drawn from the following categories: vulnerable groups (n=8; 10.4%),14,20–26 clinical dermatology (n=6; 7.8%),27–32 cosmetic dermatology (n=7; 9.1%),13,33–38 aesthetic dermatology (n=7; 9.1%),39–45 bioethics training (n=7; 9.1%),46–52 dermatological photography (n=5; 6.5%),53–57 pharmaceutical industry (n=11; 14.3%),12,58–67 AI (n=5; 6.5%),9,68–71 SM (n=9; 11.7%),11,72–79 and teledermatology (n=12; 15.6%).10,80–90 Data extracted from each article included the name of the first author, type of article, year of publication, name of the journal, thematic area, and main result (Table 2). The most important aspects are reviewed below.

Articles picked for review.

| Author | Year | Journal | Article type | Theme | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamson20 | 2017 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Commentary | Vulnerable gr. | Lack of learning on lesions in African American individuals, evaluation of the term ethnicity |

| Sullivan et al.21 | 2019 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Systematic rev. | Vulnerable gr. | Training during residency on the best management of transgender individuals is required |

| Glass et al.22 | 2020 | J Invest Dermatol. | Editorial | Vulnerable gr. | Promotion of professional development of dermatologists from ethnic minorities |

| Ortiz et al.23 | 2021 | Br J Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | Vulnerable gr. | Dermatological training in other cultures is required |

| Jones and Heath26 | 2021 | Pediatr Dermatol. | Humanities Art. | Vulnerable gr. | Knowledge of other cultures is essential to provide quality health care |

| Liu et al.24 | 2021 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | Vulnerable gr. | Education vs the use of skin-lightening products is required |

| Farshchian and Grant-Kels14 | 2022 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | Vulnerable gr. | In dermatology, it is pertinent to record ethnicity in the patient's health record for diagnosis and treatment |

| Rehman et al.25 | 2022 | Br J Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | Vulnerable gr. | Attention to Muslim patients and emphasis on the importance of the hijab |

| Lee and Bercovitch27 | 2017 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Brief consultation | Clinical derm. | Ethical considerations of the isotretinoin prescription system in the United States (iPLEDGE) |

| Stoff and Grant-Kels28 | 2017 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Brief consultation | Clinical derm. | Free melanoma screening programs could facilitate access for people with fewer resources; its impact on morbidity and mortality is unknown to this date |

| Martin et al.29 | 2018 | Dermatol. surg. | Original art. | Clinical derm. | Bioethical problems emerging from the treatment of skin cancers |

| Anderson and Keller30 | 2018 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Brief consultation | Clinical derm. | Treatment with botulinum toxin for axillary hyperhidrosis should be covered by medical insurance and not as an aesthetic procedure |

| Gitin et al.31 | 2022 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | Clinical derm. | Ethical aspects of removing benign nevi in minors for aesthetic reasons |

| Fritzsche et al.32 | 2022 | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. | Systematic rev. | Clinical derm. | Ethical aspects of searching for biomarkers in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis for diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis |

| Farris33 | 2000 | Semin Cutan Med Surg. | Original art. | Cosmetic derm. | Recommendations on selling cosmetic products in consultation: although convenient for the patients, it creates conflicts of interest |

| Ogbogu et al.34 | 2001 | Arch Dermatol. | Original art. | Cosmetic derm. | Selling cosmetic products creates conflicts of interest |

| Newburger and Caplan35 | 2006 | Arch Dermatol. | Editorial | Cosmetic derm. | Do not recommend academic collaboration with the cosmetic industry |

| Castanedo and Baumann13 | 2009 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Cosmetic derm. | Advantages and bioethical issues of selling cosmetic products |

| Buendía-Eisman36 | 2009 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Other | Cosmetic derm. | Importance of training dermatologists in cosmetic medicine; professionals must keep the same conduct as in any other procedure |

| Goldberg37 | 2009 | Dermatol Clinics. | Other | Cosmetic and aesthetic derm. | Selling cosmetic products with packaging stating “Dr.” can influence their purchase; recommendations for non-medical aesthetics |

| Whitaker et al.38 | 2012 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Cosmetic derm. | Although selling cosmetic products can be convenient for the patients, it can create conflicts of interest |

| Mascaró39 | 2001 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Other | Aesthetic derm. | Dermatologists can participate in aesthetic procedures; must be included in training and patients informed of the risks and benefits.It is not appropriate to create new needs for the patient |

| Slade et al.40 | 2012 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Aesthetic derm. | Guidelines on how to perform aesthetic procedures by non-medical personnel |

| Baumann41 | 2012 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Cosmetic and aesthetic derm. | Performing aesthetic procedures for financial reasons is valid after informing the patient and exhausting other first-line measures |

| Sachdev and Britto42 | 2014 | J Cutan Aesthet Surg. | Other | Aesthetic derm. | Ethical recommendations for performing aesthetic procedures |

| Wang et al.43 | 2018 | J Cosmet Dermatol. | Commentary | Aesthetic derm. | Dermatologists must be knowledgeable of various aesthetic techniques and warn patients about unapproved devices or techniques |

| Atiyeh et al.44 | 2020 | Aesthetic Plast Surg. | Review | Aesthetic derm. | Performing aesthetic dermatology procedures by untrained personnel can cause severe harm |

| Mosallaei and Grant-Kels45 | 2022 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | Aesthetic derm. | Recommending aesthetic procedures to patients seeking dermatological disease treatment can be problematic |

| Bercovitch and Long46 | 2007 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Other | Bioethics tr. | Establishes objectives on bioethics and activities during residency |

| Bercovitch and Long47 | 2009 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Bioethics tr. | Establishes objectives on bioethics and activities during residency |

| Aldrich and Mostow48 | 2011 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | Bioethics tr. | Importance of learning bioethics from everyday cases |

| Garg and Grant-Kels49 | 2012 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Bioethics tr. | Recommendations on how to use SM by residents, relationship with mentors and patients |

| Stoff et al.50 | 2018 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Commentary | Bioethics tr. | Establishes objectives on bioethics and activities during residency |

| Anstey51 | 2018 | Br J Dermatol. | Editorial | Bioethics tr. and pharmaceutical ind. | Importance of bioethics tr. for new residents and specialists |

| Gollnick et al.52 | 2019 | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. | Other | Bioethics tr. | Medical resident training must include medical ethics |

| Scheinfeld53 | 2004 | Arch Dermatol. | Observational | Derm. photography | Importance of obtaining IC and keeping confidentiality |

| Kunde et al.54 | 2013 | Australas J Dermatol. | Original art. | Derm. photography | Survey on the use of photography by dermatologists |

| Nielson et al.55 | 2015 | Dermatol Online J. | Original art. | Derm. photography | Importance of obtaining IC and confidentiality |

| Kazemi et al.56 | 2019 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Brief consultation | Derm. photography | Requirements for obtaining and storing images |

| Arimany et al.57 | 2020 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Practical Derm. | Derm. photography | Respecting principles on bioethics and codes of ethics |

| Mascaro and Neumann12 | 2000 | Arch Dermatol. | Other | Pharmaceutical ind. | Questioning funding of congresses and payment for lectures |

| Sams and Freedberg58 | 2000 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Opinion | Pharmaceutical ind. | Although collaboration with the industry is necessary it creates conflicts of interest |

| Perlis and McDonald59 | 2003 | Cutis | Editorial | Pharmaceutical ind. | Receiving gifts is unethical; payment for educational activities is considered valid |

| Kuehn60 | 2005 | JAMA | Other | Pharmaceutical ind. | In the United States, dermatology residencies were funded by the industry |

| Higgins61 | 2007 | Dermatol Online J. | Original art. | Pharmaceutical ind. | Gifts and lunches from the industry can influence drug prescription |

| Miner and Menter62 | 2009 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Pharmaceutical ind. | Ethical recommendations on collaboration with the industry |

| Alikhan et al.63 | 2010 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Commentary | Pharmaceutical ind. | Distribution of drug samples creates conflicts of interest |

| Reid et al.64 | 2012 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Pharmaceutical ind. | Distribution of drug samples creates a conflict of interest |

| Gahalaut et al.65 | 2014 | Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. | Original art. | Pharmaceutical ind. | Drug advertisements in scientific journals influence doctors |

| Ashack et al.66 | 2015 | Br J Dermatol. | Other | Pharmaceutical ind. | Importance of declaring conflicts of interest and relationships with the industry |

| Li et al.67 | 2019 | JAMA Dermatol. | Original art. | Pharmaceutical ind. | Patient associations do not always declare conflicts of interest, or the exact amount of funding received from the industry |

| Kovarik et al.68 | 2019 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Commentary | AI | Importance of verifying safety and efficacy and obtaining IC |

| Du-Harpur et al.69 | 2020 | Br J Dermatol. | Review | AI | Benefit in determining the priority level of consultations |

| Young et al.70 | 2020 | J Invest Dermatol. | Review | AI | AI may perpetuate inequalities due to training with European and Asian patients and not with African American skins, in addition to its cost |

| Tracy et al.71 | 2021 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | AI | Medical images can be provided for AI training as long as they cannot be identified |

| Willem et al.9 | 2022 | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. | Original art. | AI | Lack of representation of certain skin colors and the requirement of access and IT knowledge can perpetuate inequalities; there may be diagnostic errors |

| Luo et al.79 | 2009 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | SM | Bioethics issues derived from using e-mail accounts |

| Taberner11 | 2016 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Review | SM | Clinical practice guidelines for responsible use of SM |

| Fattore et al.72 | 2019 | Int J Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | SM | Use of instant messaging applications can compromise IC and information security |

| Ranpariya et al.73 | 2020 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Letter to the Ed. | SM | Dermatologist participation on Instagram is important for educational purposes |

| Militelo et al.74 | 2021 | Curr Dermatol Rep. | Review | SM | Advantages and disadvantages of using SM |

| Muzumdar et al.75 | 2021 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | SM | Advertising cosmetic products on SM is ill-advised |

| Beltrami et al.76 | 2022 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | SM | Issues associated with publishing before-and-after photos on SM |

| Morris et al.77 | 2022 | Int J Environ Res Public Health. | Other | SM | Use of instant messaging can facilitate access to dermatology in remote areas; IC is not always obtained |

| Haykal et al.78 | 2023 | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. | Letter to the Ed. | SM | Risks from the improper use of SM for promoting aesthetic dermatology |

| Grenier et al.10 | 2009 | Clin Dermatol. | Other | Teledermatology | Ethical issues and good clinical practice guidelines |

| Roman and Jacob80 | 2014 | J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. | Other | Teledermatology | Importance of complying with principles on bioethics in teledermatology |

| Fogel et al.81 | 2015 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Other | Teledermatology | Risks of using teledermatology in pediatrics (lack of IC) |

| Rubin and Kovarik82 | 2015 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Brief consultation | Teledermatology | Could reduce disparities in access to dermatological consultations |

| Pala et al.83 | 2020 | Postepy Dermatol Alergol | Review | Teledermatology | Possibility of improving access in rural areas and becoming a training tool for doctors |

| Burg84 | 2020 | J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol | Commentary | Teledermatology | Provides support and health care to isolated patients |

| Arimany et al.85 | 2020 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Review | Teledermatology | Must ensure IC is included and privacy kept |

| Rismiller et al.86 | 2020 | J Dermatolog Treat. | Other | Teledermatology | Importance of obtaining IC; can facilitate access in remote areas |

| Elmas et al.87 | 2020 | Dermatol Ther. | Letter to the Ed. | Teledermatology | Importance of obtaining IC and guaranteeing image security |

| Gómez et al.88 | 2021 | Actas Dermosifiliogr. | Other | Teledermatology | Attitude of the code of ethics and need for obtaining IC |

| Farr et al.89 | 2021 | Am J Clin Dermatol. | Review | Teledermatology | Importance of obtaining IC while keeping privacy |

| Korman and Fabbro90 | 2021 | J Am Acad Dermatol. | Journal Club | Teledermatology | Private teledermatology with drug prescriptions can have risks |

IC, informed consent; vulnerable gr., vulnerable groups; clinical derm., clinical dermatology; cosmetic derm., cosmetic dermatology; aesthetic derm., aesthetic dermatology; bioethics tr., bioethics training; derm. photography, dermatological photography; pharmaceutical ind., pharmaceutical industry; AI, artificial intelligence; SM, social media.

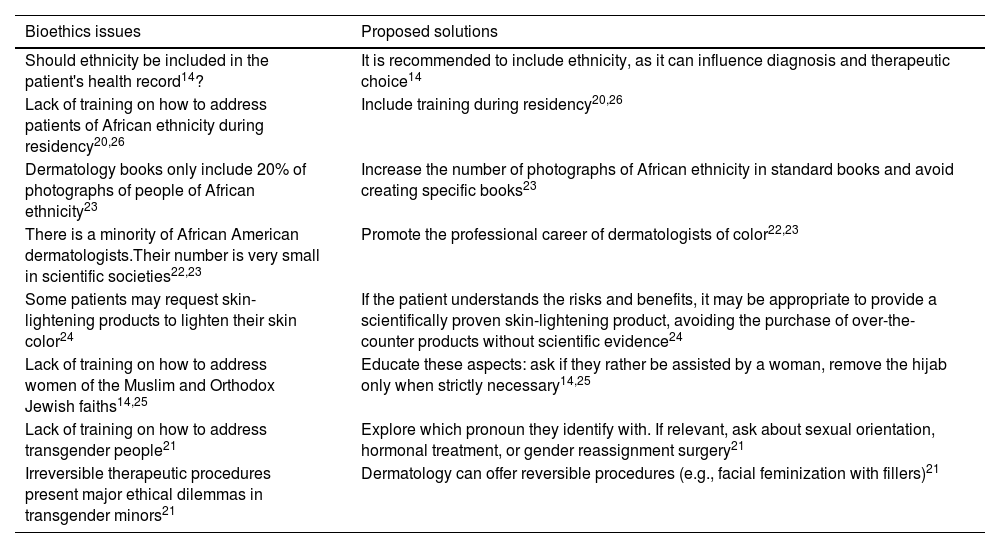

Bioethical issues have been identified in association with the doctor-patient relationship due to ethnicity, religion, and gender change. Most conflicts focus on the lack of training on how to treat these patients, which can undermine the clinical relationship. To avoid this, training programs during residency should include these aspects.23–25 The CDM-E, CDM-AMA, and EPE-AAD advocate for treating all patients with the same diligence, without discrimination of any kind.16,17,19 Conflicts and proposed solutions are shown in Table 3.

Bioethics issues related to vulnerable groups.

| Bioethics issues | Proposed solutions |

|---|---|

| Should ethnicity be included in the patient's health record14? | It is recommended to include ethnicity, as it can influence diagnosis and therapeutic choice14 |

| Lack of training on how to address patients of African ethnicity during residency20,26 | Include training during residency20,26 |

| Dermatology books only include 20% of photographs of people of African ethnicity23 | Increase the number of photographs of African ethnicity in standard books and avoid creating specific books23 |

| There is a minority of African American dermatologists.Their number is very small in scientific societies22,23 | Promote the professional career of dermatologists of color22,23 |

| Some patients may request skin-lightening products to lighten their skin color24 | If the patient understands the risks and benefits, it may be appropriate to provide a scientifically proven skin-lightening product, avoiding the purchase of over-the-counter products without scientific evidence24 |

| Lack of training on how to address women of the Muslim and Orthodox Jewish faiths14,25 | Educate these aspects: ask if they rather be assisted by a woman, remove the hijab only when strictly necessary14,25 |

| Lack of training on how to address transgender people21 | Explore which pronoun they identify with. If relevant, ask about sexual orientation, hormonal treatment, or gender reassignment surgery21 |

| Irreversible therapeutic procedures present major ethical dilemmas in transgender minors21 | Dermatology can offer reversible procedures (e.g., facial feminization with fillers)21 |

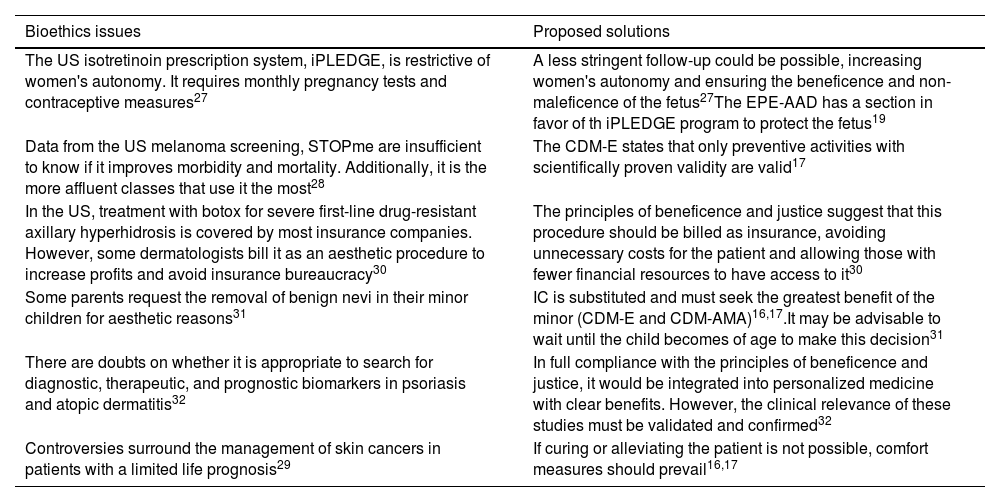

Bioethical problems have been identified in association with the prescription of isotretinoin27 and free melanoma screening in the United States. 28Issues also arose with the funding of axillary hyperhidrosis therapy with botulinum toxin,30 excision of nevi for aesthetic reasons in pediatrics,31 search for biomarkers in inflammatory diseases,32 and the management of skin cancers in patients with guarded prognosis.29 Problems and proposed solutions are available in Table 4.

Bioethics issues related to clinical dermatology.

| Bioethics issues | Proposed solutions |

|---|---|

| The US isotretinoin prescription system, iPLEDGE, is restrictive of women's autonomy. It requires monthly pregnancy tests and contraceptive measures27 | A less stringent follow-up could be possible, increasing women's autonomy and ensuring the beneficence and non-maleficence of the fetus27The EPE-AAD has a section in favor of th iPLEDGE program to protect the fetus19 |

| Data from the US melanoma screening, STOPme are insufficient to know if it improves morbidity and mortality. Additionally, it is the more affluent classes that use it the most28 | The CDM-E states that only preventive activities with scientifically proven validity are valid17 |

| In the US, treatment with botox for severe first-line drug-resistant axillary hyperhidrosis is covered by most insurance companies. However, some dermatologists bill it as an aesthetic procedure to increase profits and avoid insurance bureaucracy30 | The principles of beneficence and justice suggest that this procedure should be billed as insurance, avoiding unnecessary costs for the patient and allowing those with fewer financial resources to have access to it30 |

| Some parents request the removal of benign nevi in their minor children for aesthetic reasons31 | IC is substituted and must seek the greatest benefit of the minor (CDM-E and CDM-AMA)16,17.It may be advisable to wait until the child becomes of age to make this decision31 |

| There are doubts on whether it is appropriate to search for diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic biomarkers in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis32 | In full compliance with the principles of beneficence and justice, it would be integrated into personalized medicine with clear benefits. However, the clinical relevance of these studies must be validated and confirmed32 |

| Controversies surround the management of skin cancers in patients with a limited life prognosis29 | If curing or alleviating the patient is not possible, comfort measures should prevail16,17 |

CDM-AMA, American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics; CDM-E, Spanish Medical Code of Ethics; IC, informed consent; EPE-AAD, Standards of Professionalism and Ethics for Dermatologists by the American Academy of Dermatology.

Although the sale of cosmetic products in private clinics is a common practice, this creates conflicts of interest. This can be done by non-medical personnel and be accompanied by financial incentives.13,33,34,38 Sometimes, product packaging includes “Dr. X” or the logo of a university/public institution to promote sales.37,38

Selling cosmetic products could be morally acceptable if conflicts of interest are declared, the cosmetic product is backed by scientific evidence, the risk-benefit ratio of its use has been explained, and other alternatives are suggested. Additionally, magistral formulas not available on the market could be suggested too.13,33,34,36,38 Some authors say that academic institutions and dermatology services should be particularly cautious in their relationship with the industry.35 The recommendation of cosmetic products could be delegated to trained personnel.13

The CDM-E, CDM-AMA, EPE-AAD, and CE-AEDV emphasize the importance of declaring the conflicts of interest, while the EPE-AAD and CE-AEDV prohibit the use of their logos on cosmetic products.15–17,19 The CDM-E does not allow doctors to sell drugs or other products for therapeutic purposes to patients.17

Aesthetic dermatologyProblems have been identified on whether it is appropriate for dermatologists to perform aesthetic procedures,41–44 especially for patients seeking treatment for other disease,39,45 and whether these procedures can be performed by nurses and assistants.37,40,42,44 Problems and detected solutions are available in Table 5.

Bioethics issues related to aesthetic dermatology.

| Bioethics issues | Proposed solution |

|---|---|

| Is it appropriate for dermatologists to perform aesthetic procedures39,41–44? | The CE-AEDV and EPE-AAD include aesthetics among the dermatologist's functions15,19. The patient should be properly informed about their condition, benefits and risks, therapeutic alternatives, and expected outcomes39,41–44 |

| Can nurses and assistants perform aesthetic treatments37,40,42,44? | According to the CDM-E, all specialized medical acts must be performed by a specifically qualified physician17; EPE-AAD indicates that they can perform them if trained and informed about their qualification19 |

| Is it appropriate to recommend aesthetic procedures to patients seeking treatment for other dermatological conditions39,45? | Although it offers advantages such as presenting a never-before considered option, it can also cause emotional distress over a non-pathological issue. Some authors recommend not offering them39,45 |

CDM-E, Spanish Medical Code of Ethics; CE-AEDV, Ethical Code and Good Governance of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; EPE-AAD, Standards of Professionalism and Ethics for Dermatologists by the American Academy of Dermatology.

In the routine clinical practice, we face bioethical problems such as interaction with the industry and minors, off-label drug prescriptions... However, training in this area is often insufficient during residency.46,48,52 Resident tutors need to be further involved, as they are the role models for residents. Suggested activities include seminars, article discussions, and case-based learning. Teaching should include the declaration of potential conflicts of interest, relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, establishing boundaries with other health care workers and patients, and responsible use of social media.46,49,51 The AEDV and other institutions emphasize the need for training in “dermoethics” and deontology during residency and for specialists with a focus on everyday problems.15–17,19

Dermatological photographyPhotography is part of the health record, and it is necessary to request informed consent (IC), which should include the purposes and destinations of the image (such as publication or use in conferences); otherwise, the patient's autonomy could be violated or damaged. Some authors believe that even when the photograph cannot be identified, the corresponding IC should be requested since nearby anatomical areas, scars, tattoos, or piercings make the image identifiable to third parties.53,54,56,57 It is recommended to use storage systems provided by the hospital and avoid using mobile phones, which may pose a security breach.54,56,57 The currently available various codes of ethics emphasize the importance of obtaining IC for patient images and their use for different purposes, such as medical care, publication of scientific articles, or teaching.15–17,19

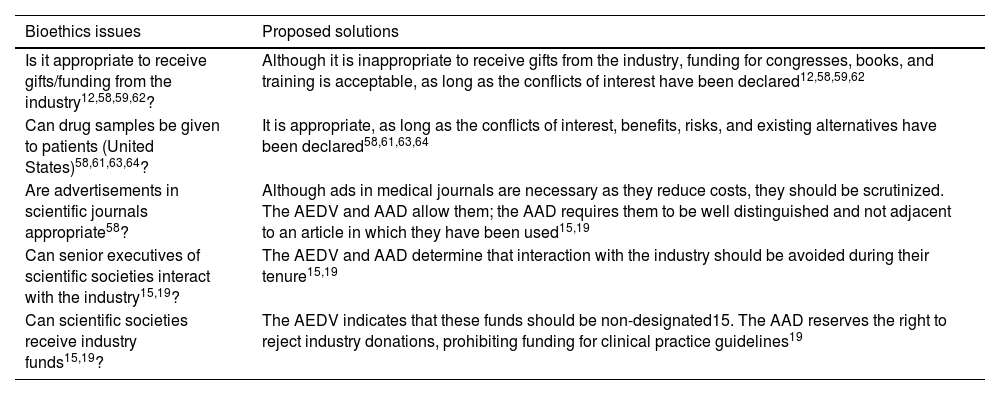

The pharmaceutical industryIndustry contact with professionals is increasingly early, affecting residents and medical students, and intends to influence their decision-making and prescribing habits.12,58,59,61,62,66 Identified problems and proposed solutions are collected in Table 6.

Bioethics issues related to the pharmaceutical industry.

| Bioethics issues | Proposed solutions |

|---|---|

| Is it appropriate to receive gifts/funding from the industry12,58,59,62? | Although it is inappropriate to receive gifts from the industry, funding for congresses, books, and training is acceptable, as long as the conflicts of interest have been declared12,58,59,62 |

| Can drug samples be given to patients (United States)58,61,63,64? | It is appropriate, as long as the conflicts of interest, benefits, risks, and existing alternatives have been declared58,61,63,64 |

| Are advertisements in scientific journals appropriate58? | Although ads in medical journals are necessary as they reduce costs, they should be scrutinized. The AEDV and AAD allow them; the AAD requires them to be well distinguished and not adjacent to an article in which they have been used15,19 |

| Can senior executives of scientific societies interact with the industry15,19? | The AEDV and AAD determine that interaction with the industry should be avoided during their tenure15,19 |

| Can scientific societies receive industry funds15,19? | The AEDV indicates that these funds should be non-designated15. The AAD reserves the right to reject industry donations, prohibiting funding for clinical practice guidelines19 |

AAD, American Academy of Dermatology; AEDV, Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Some studies have already demonstrated that AI can match or surpass a group of dermatologists, reduce costs, and increase health care coverage. However, there are still doubts on its safety, efficacy, confidentiality, and equitable access.9,68–71 Large image databases are required for AI to work properly because if these databases only contain lesions from Asian and European patients, they could make more diagnostic errors or promote less follow-up for African ethnicities.9,70,71 IC should be obtained before using images for this purpose.70,71 On the other hand, the financial cost associated with software, cameras, and infrastructure could reduce implementation in less resourceful areas, thus increasing inter-regional disparities. Additionally, the IT system must be secure to prevent photographs from being used with other purposes.9,70

The CDM-E allows the use of AI, as long as it has been designed and develop for the benefit of society, and ensures validity, safety, and traceability while always preserving patient privacy and confidentiality.17

Social mediaAlthough patients seek information on SM, most content is created by people outside the dermatology setting. Therefore, the participation of dermatologists is advisable to inform patients, doctors, and residents.73,74 SM can also be used for advertising and marketing private clinics, provided it is done respectfully and professionally, avoiding unrealistic results and expectations.11,76,78 Therefore, using “before and after” photos of an aesthetic procedure after obtaining the corresponding valid IC, explaining the associated risks and benefits and the possibility of revocation is required.11,76,78 Another use is advertising cosmetic products, which creates conflicts of interest and can be controversial,74,75 or receiving teleconsultations, which is ill-advised as there are other regulated modalities of teledermatology.72,77,79 The CDM-E and CDM-AMA allow the use of SM for assistance, education, research, and marketing, provided ethical standards are respected.16,17

TeledermatologyThe use of teledermatology can benefit patients by shortening wait times, reducing costs, and increasing dermatological coverage for immobilized patients or those in hard-to-reach areas.80,82–89 Additionally, it can also prevent damage to patients, such as COVID-19 infection, and serve as training for dermatology or family medicine residents.85–87,89 However, the use of teledermatology raises questions related to patient safety and confidentiality. It is important to inform patients of the limitations associated with teledermatology (no total body surface examination or image quality).10,80,83,85–88,90 Prescribing drugs is contentious since it is often impossible to identify the patient, inform them, or explain therapeutic alternatives.81

The CDM-E, CDM-AMA, and EPE-AAD include sections on telemedicine, where its use is permitted, provided ethical standards such as obtaining IC, preserving confidentiality, and declaring conflicts of interest are maintained.16,17,19 The CDM-AMA allows prescriptions if patient identity is ensured16, while the EPE-AAD requires an initial in-person visit before prescribing via teleconsultation.19

DiscussionDermatology has undergone significant changes in recent years; topics such as aesthetic medicine,40 AI68, social media,79 and teledermatology10 have gained unexpected social relevance. This narrative review has identified that there is bioethical concern for these aspects and others such as vulnerable groups,20 clinical27 and cosmetic dermatology,33 bioethics training,46 dermatological photography,53 and the pharmaceutical industry.59

Scientific community is interested in studying these topics, as demonstrated by the Journalof the American Academy of Dermatology, which dedicates a full section to this discipline91 (23 [30.6%] reviewed articles come from this journal, and 6 [7.8%] from Actas Dermosifiliográficas11,36,39,57,85,88). Additionally, as it has happened in the history of bioethics, societal events lead to the drafting of these articles, such as George Floyd's death and articles addressing racism in dermatology,22,23 or COVID-19 and teledermatology.85–87,89

Various authors share the perception that dermatologists should treat all patients with deserved respect and equality, regardless of their culture, religion, or sexual orientation.14,20,21,25 They also address aspects of clinical practice, such as the American system of isotretinoin prescription27 or the American melanoma screening program,28 which differ from the national clinical practice. Although, in Spain, dermatologists must warn patients of associated teratogenic risks and offer contraceptives systems, monthly gestational screening is not mandatory;27 free melanoma screening programs are also available. Yet these bioethical issues have not been addressed from the Spanish perspective.

Aesthetic and cosmetic dermatology are traditional sources of friction due to the possible underlying financial interest. Cosmetic dermatology is permissible, as long as the conflicts of interest have been declared, therapeutic alternatives have been explained; and products are sold with demonstrated evidence.13,33,34,38 Some authors recommend that dermatology services and departments should not engage with the cosmetic industry.35 In aesthetic dermatology, it is necessary to inform about the risks and benefits, alternatives, and whether a dermatologist or an assistant is performing the procedure.40–44 The CDM-E does not allow any medical acts to be performed by any members of the auxiliary staff.17

There is also a consensus on training young doctors in bioethics during residency, especially regarding the Pharmaceutical industry.46,48,51,52 Although collaboration with the industry is valid to fund congress attendance and continuing education, the conflicts of interest must be declared. Other aspects such as the distribution of samples or advertisements in scientific journals can be appropriate if subjected to certain controls.12,58,59,61,62,64

Although photography is essential for our specialty, obtaining informed consent (IC) and preserving patient confidentiality and privacy must be ensured. The use of mobile phones should not lead to a breach of these.53,54,56,57 These photographs have enabled the development of AI and teledermatology. For appropriate AI use, it is crucial to train software with images of lesions of patients from different ethnicities so that all patients can benefit the same.9,70,71 Teledermatology increases access to the specialty by reducing inequalities.10,80,84–88,90 Nonetheless, prescribing drugs via teledermatology is controversial, as it is usually not possible to establish a dialogue with the patient.81

Finally, the use of SM is appropriate as it educates not only the public but also doctors. SM can be used for promoting private clinics. For all these purposes, compliance with the same ethical standards as in regular clinical practice is required.11,75,76,78

Entities such as OMC, AEDV, AMA, or AAD have developed ethical codes that gather the necessary standards to preserve integrity, transparency, professionalism, and medical commitment to society. The CDM-E and CDM-AMA have been updated throughout the years and include sections on new topics, such as the use of social media, AI, or telemedicine.16,17

The EPE-AAD and CE-AEDV focus on their relationship with the pharmaceutical industry: although they recognize the need for funding, they also warn and create mechanisms to avoid its influence. Both discourage relationships with the industry during the tenure of their executives, and both emphasize the importance of declaring the conflicts of interest.15,19 They also include the aesthetic function as part of the dermatologist's duties.8,15,19 However, these codes that are more specific to dermatologies are not as comprehensive as the CDM-E and CDM-AMA. The CE-AEDV does not address the use of SM, AI, or teledermatology, while the EPE-AAD does not make any references to AI or social media either.19

Of note that some bioethical issues have not been addressed by dermatology journals. For example, SM is flooded with giveaways offering dermatological therapies in exchange for sharing content. The CDM-E states that it is unethical for a doctor to offer services in contests or sale discounts.17

The present review has limitations, such as less stringent inclusion criteria and inadequate weighting of the evidence of included articles. Aspects associated with venereology were not included either

In conclusion, as dermatology has become more sophisticated and diverse job opportunities have emerged, bioethical issues have increased. Some of these innovations have not been legislated, lacking binding regulations. Bioethics is vital, exercising control before and after these matters are legislated. Since its origin, dermatology has been focused on protecting human dignity.

ConclusionsCurrently, bioethical issues related to vulnerable groups, clinical, aesthetic, and cosmetic dermatology, the pharmaceutical industry, dermatological photography, teledermatology, and SM have been reported. There is consensus on the need for bioethics training to address these issues.

Various authors highlight the importance of declaring all possible conflicts of interest, respecting the patient's autonomy, confidentiality, and privacy. Aesthetic dermatology, the sale of cosmetics, AI, and teledermatology are ethically appropriate if they meet the same standards as our routine clinical practice. It is advisable for dermatologists to participate in SM to educate the public.

The CDM-E and CDM-AMA have adapted to most of these innovations, including sections on telemedicine, SM, and AI. Although the CE-AEDV and EPE-AAD focus on the pharmaceutical industry and need for bioethics training they omit some aspects of new technologies, which need updating.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.