Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a major multiple organ complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and skin involvement is associated with substantial mortality, morbidity and reduction in quality of life. However, more than half of patients are refractory to current first-line therapy and there is still a lack of high-level evidence regarding alternative therapeutic agents. This systematic review was conducted by two independent reviewers who searched and screened records published from database inception to May 2024 in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, using prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria aligned with the study objective. Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias and quality of evidence of trials eligible for review. Seven randomized controlled trials of extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) with standard therapy, imatinib, entospletinib with prednisone, ruxolitinib, and ibrutinib with prednisone were eligible for inclusion. Ruxolitinib demonstrated superiority versus standard therapy and placebo with an overall response rate of 41.5% and a reduction in body surface area affected from 14.5% down to 6.2%. No other treatments conferred a statistically significant benefit versus standard therapy or placebo. Entospletinib was markedly inferior to placebo. Although all 7 trials demonstrated some risk of bias, they were found to have a moderate-to-high quality of evidence. In conclusion, of all therapeutic agents reviewed, only ruxolitinib demonstrated high-level evidence of a modest efficacy in treating cutaneous cGVHD and should be considered as a line of therapy in addition to current first-line therapy. Further high-level studies are needed to identify alternative therapeutic agents and validate their efficacy profile.

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) remains a major multiple organ complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) therapy. Occurring in up to 85% of patients on HSCT (typically for hematological malignancies),1–3 cGVHD is the leading post-HSCT cause of mortality other than relapse,4 and is associated with severe impairments in quality of life.5 Risk factors include female donor-to-male recipient, greater age, prior grade III–IV acute GVHD, donor-recipient human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch, and use of peripheral blood rather than bone marrow stem cell transplant.6,7 The natural history and pathogenesis of cGVHD has been poorly understood until the last decade, and accordingly, few identifiable therapeutic targets have been identified.8,9 The current model of cGVHD pathogenesis is triphasic, consisting of early inflammation of host tissues; thymic injury and dysregulation of donor T and B cells; and fibrosis of host tissues with end-organ damage.10 The U.S. National Institutes of Health diagnostic criteria are defined by clinical signs in specific organ-systems, including the skin, GI tract, lungs, liver, and eyes, as well as nails, hair, mouth, and genitalia.11

Of these organ-systems, the skin is involved in up to 90% of cGVHD patients. Cutaneous cGVHD typically occurs earliest versus other organs, and takes the form of the earlier-onset lichenoid (lcGVHD) or later-onset sclerodermatous (scGVHD) subtypes.1 The scGVHD subtype is present in up to 20% of patients within 3 years after transplant12 and is associated with a 5-year mortality rate of 12%.13 If not successfully treated, cutaneous cGVHD patients face severe ongoing adverse effects, including an increased risk of cutaneous malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma, likely due to the inflammatory processes underlying cGVHD.14,15 Fibrotic changes caused by scGVHD result in fixed joint contractures which severely restrict range of motion,16 which in turn substantially reduces the patients’ quality of life.17 Increased skin thickness, fragility, and tightening in scGVHD also give rise to a greater risk of cutaneous infections, as well as a greater risk of cutaneous ulcers.16

Despite the use of prophylactic measures such as anti-thymocyte globulin and T-cell depletion,18 the incidence rate of cGVHD (including cutaneous subtypes) among post-HSCT patients is still substantial, meaning effective treatments are also required.19 The current first-line therapy for mild cutaneous presentations is topical corticosteroids, and for more severe presentations, systemic corticosteroid therapy. At least 50% of patients will be refractory to first-line therapy, requiring the use of other, more potent immunosuppressants or phototherapeutic approaches.20,21 However, there are currently few therapeutic guidelines or standardized treatments for the use of these agents in treating cGVHD, and even fewer for treating cGVHD in individual organ-systems.22 It is necessary to identify treatments effective for cutaneous cGVHD specifically because different organ-systems do not necessarily respond uniformly to therapeutic agents.

Therefore, this systematic review aimed to identify all therapeutic agents for cGVHD which have demonstrated high-level evidence of efficacy in improving skin-related outcome measures.

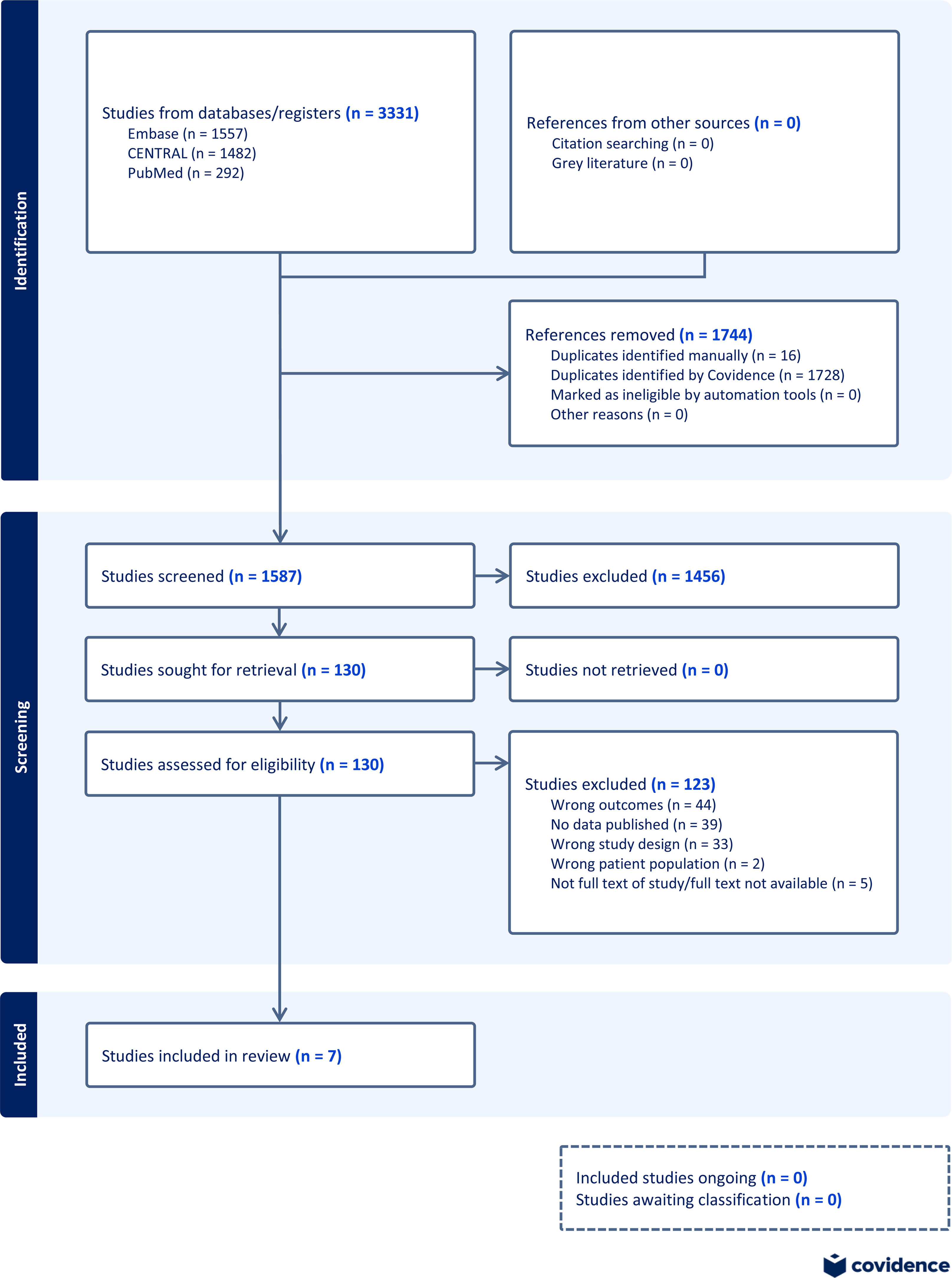

Materials and methodsWe conducted a systematic review of the existing literature, with a search and screening process conforming to guidelines described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.23 The study protocol was registered on the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO ID CRD42024567934).

Eligibility criteriaA Patients, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes and Study type (PICOS) framework based on the aims of this study was established. The PICOS framework was modified to account for the study aim of evaluating a range of treatments rather than a single treatment. The PICOS framework was used to define inclusion and exclusion criteria before conducting the literature search. Records were considered eligible for data extraction and review if they met the following criteria: (i) patients diagnosed with cutaneous cGVHD; (ii) at least one treatment for cGVHD; (iii) change in cutaneous signs of cGVHD as an outcome measure; (iv) was a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Records were excluded if they met the following criteria: (i) patients diagnosed with acute GVHD; (ii) studies evaluating the efficacy profile of prophylaxis versus GVHD; (iii) no skin-specific outcome measures; (iv) not a randomized controlled trial; (v) duplicates of other records; (vi) records not available in English; (vii) records without published data; (viii) no full text available.

Search strategyThese inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to construct a high-sensitivity set of search terms and medical subject headings (eMethods 1: Search strategy). This was refined with assistance from a specialist librarian. This was used to search across PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from inception to May 27th 2024. Search results were limited to RCTs. There were no restrictions on date of publication.

Study selectionRecords retrieved were imported into Covidence systematic review software24 for screening and review. Duplicate records were automatically excluded by the software. Two reviewers (MZ and PFP) independently undertook title, abstract, and keyword screening for relevance based on the pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Records were deemed suitable for full-text screening if they met all inclusion/exclusion criteria, or if there was insufficient evidence to decide otherwise. Conflicts were resolved by discussion. Then, two reviewers (MZ and PFP) independently reviewed the full text of the remaining records for relevance, again using the pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Records satisfying all inclusion/exclusion criteria were deemed eligible for data extraction.

Data extractionTwo reviewers (MZ and MMP) independently used a standardized table to extract data from included studies. This included study details (authors, year of publication, study design, sample size, patient demographics, proportion of patients who had been on prophylaxis, proportion of patients who had been on prior treatments), intervention and controls, and results (outcome measures, outcomes, statistical significance).

Risk of bias and quality of evidence assessmentTwo reviewers (MZ and MMP) independently used the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool25 to assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Then, two reviewers (MZ and MMP) assessed the quality of included studies according to Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.26

ResultsThe search strategy identified 1587 unique records after duplicate removal. Following the initial screening, 130 records were selected for full-text review, of which 7 randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria for data extraction. The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

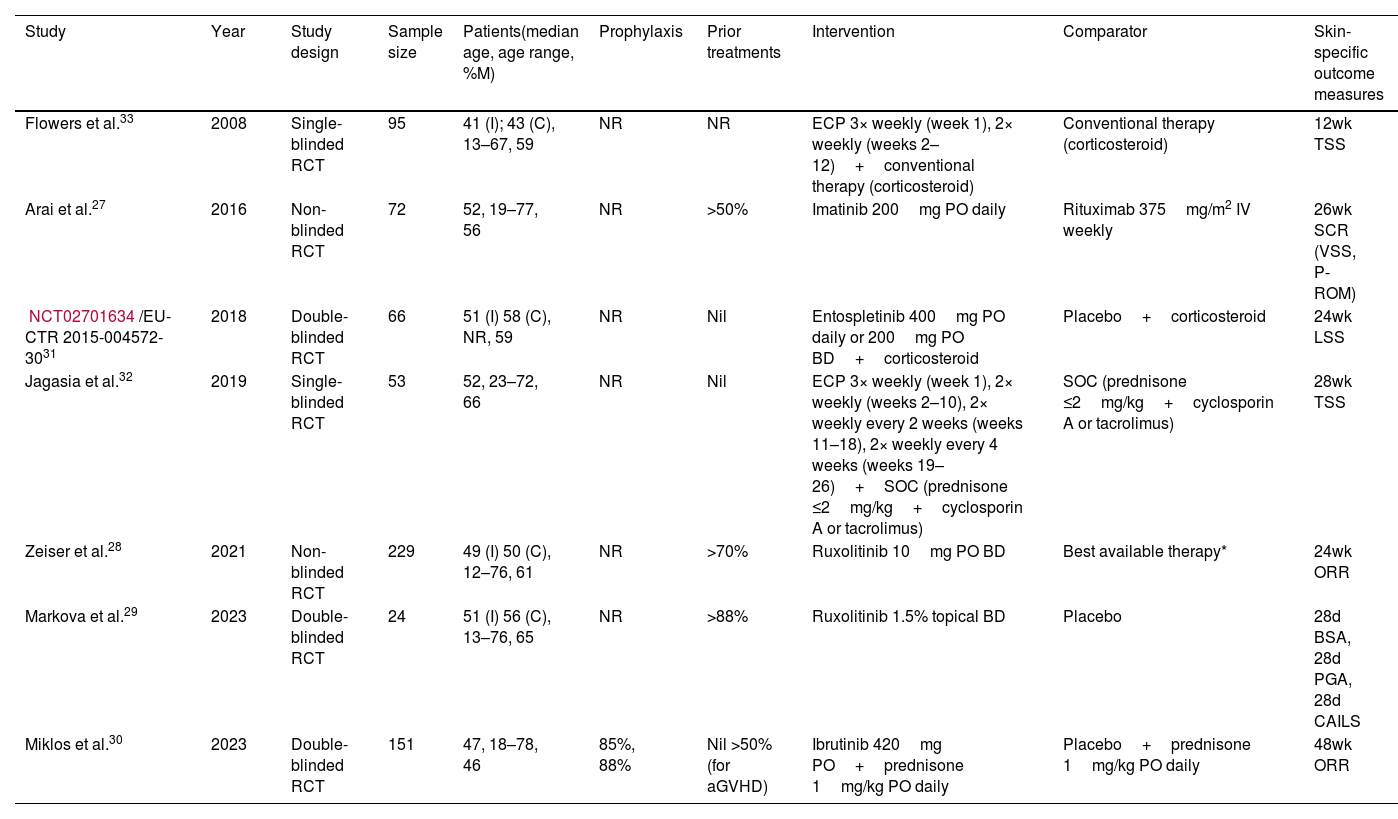

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Results from included studies were published between 2008 and 2023. Sample sizes ranged from 24 to 329. Treatments studied included extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) with standard therapy, imatinib, entospletinib with prednisone, ruxolitinib, and ibrutinib with prednisone. Control treatments included physician-selected best available/conventional/standard of care therapy, rituximab, placebo with prednisone, and placebo alone. Six studies specified whether patients had previously received other treatments, with >50% of patients having received treatment for cGVHD in 3 studies,27–29 and >50% of patients from another study30 having received treatment for aGVHD but not cGVHD. Patients from 2 studies31,32 received the intervention or comparator as first-line therapy. One study30 reported details of cGVHD prophylaxis used, with >85% of patients from that study having received prophylaxis. Two studies28,30 measured treatment efficacy in terms of overall response rate (ORR), 232,33 by total skin score (TSS), 127 by significant clinical response (SCR), and 129 by body surface area (BSA) affected (eResults 1: Description of outcome measures).

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Year | Study design | Sample size | Patients(median age, age range, %M) | Prophylaxis | Prior treatments | Intervention | Comparator | Skin-specific outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flowers et al.33 | 2008 | Single-blinded RCT | 95 | 41 (I); 43 (C), 13–67, 59 | NR | NR | ECP 3× weekly (week 1), 2× weekly (weeks 2–12)+conventional therapy (corticosteroid) | Conventional therapy (corticosteroid) | 12wk TSS |

| Arai et al.27 | 2016 | Non-blinded RCT | 72 | 52, 19–77, 56 | NR | >50% | Imatinib 200mg PO daily | Rituximab 375mg/m2 IV weekly | 26wk SCR (VSS, P-ROM) |

| NCT02701634/EU-CTR 2015-004572-3031 | 2018 | Double-blinded RCT | 66 | 51 (I) 58 (C), NR, 59 | NR | Nil | Entospletinib 400mg PO daily or 200mg PO BD+corticosteroid | Placebo+corticosteroid | 24wk LSS |

| Jagasia et al.32 | 2019 | Single-blinded RCT | 53 | 52, 23–72, 66 | NR | Nil | ECP 3× weekly (week 1), 2× weekly (weeks 2–10), 2× weekly every 2 weeks (weeks 11–18), 2× weekly every 4 weeks (weeks 19–26)+SOC (prednisone ≤2mg/kg+cyclosporin A or tacrolimus) | SOC (prednisone ≤2mg/kg+cyclosporin A or tacrolimus) | 28wk TSS |

| Zeiser et al.28 | 2021 | Non-blinded RCT | 229 | 49 (I) 50 (C), 12–76, 61 | NR | >70% | Ruxolitinib 10mg PO BD | Best available therapy* | 24wk ORR |

| Markova et al.29 | 2023 | Double-blinded RCT | 24 | 51 (I) 56 (C), 13–76, 65 | NR | >88% | Ruxolitinib 1.5% topical BD | Placebo | 28d BSA, 28d PGA, 28d CAILS |

| Miklos et al.30 | 2023 | Double-blinded RCT | 151 | 47, 18–78, 46 | 85%, 88% | Nil >50% (for aGVHD) | Ibrutinib 420mg PO+prednisone 1mg/kg PO daily | Placebo+prednisone 1mg/kg PO daily | 48wk ORR |

BSA: body surface area; C: comparator arm; CAILS: composite assessment of index lesion severity; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis; I: intervention arm; LSS: Lee symptom scale; NR: not reported; ORR: overall response rate; PGA: physician's global assessment; P-ROM: photographic range of motion; RCT: randomised-controlled trial; SCR: significant clinical response; SOC: standard of care; TSS: total skin score; VSS: Vienna skin score.

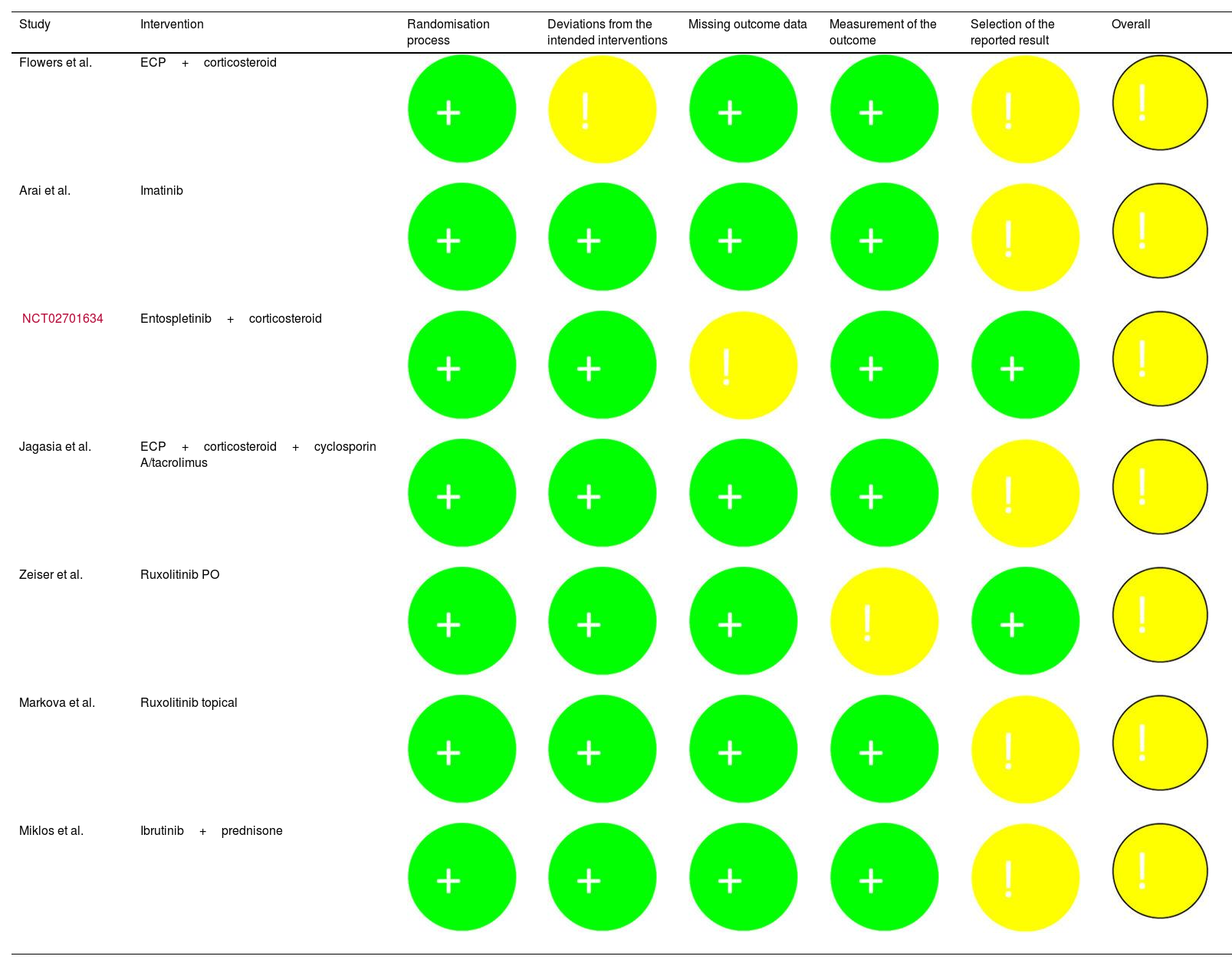

The risk of bias assessment by primary outcome for each study is shown in Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment (Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool).

| Study | Intervention | Randomisation process | Deviations from the intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported result | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flowers et al. | ECP+corticosteroid | ||||||

| Arai et al. | Imatinib | ||||||

| NCT02701634 | Entospletinib+corticosteroid | ||||||

| Jagasia et al. | ECP+corticosteroid+cyclosporin A/tacrolimus | ||||||

| Zeiser et al. | Ruxolitinib PO | ||||||

| Markova et al. | Ruxolitinib topical | ||||||

| Miklos et al. | Ibrutinib+prednisone |

+: low risk of bias; !: some concerns around bias; -: high risk of bias; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis.

All 7 studies contained features that were of some concern, mainly pertaining to bias in the measurement of outcomes and the potential for selection bias in reported results.

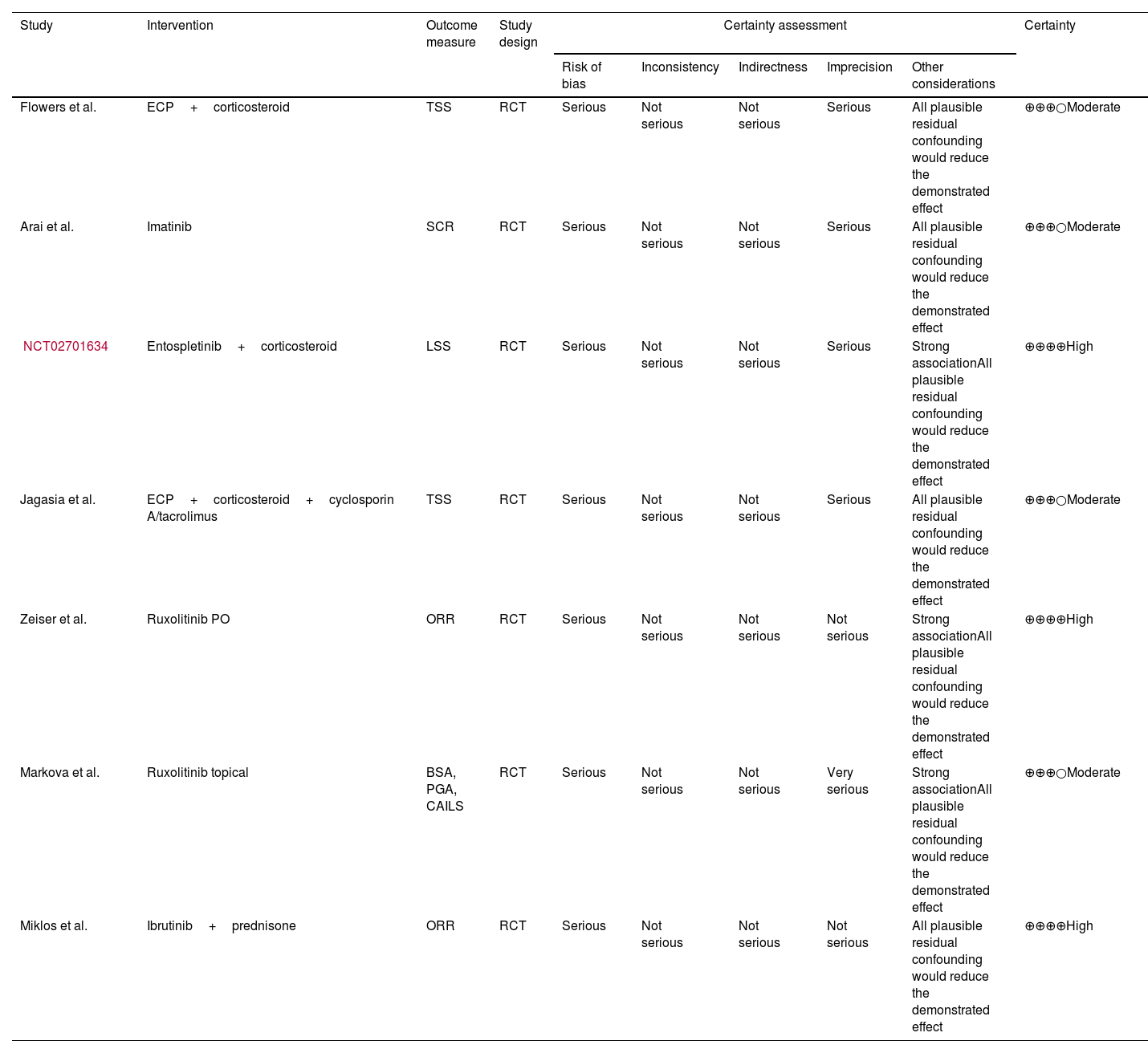

The quality of evidence assessment by primary outcome is shown in Table 3.

Quality of evidence assessment (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria).

| Study | Intervention | Outcome measure | Study design | Certainty assessment | Certainty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||||

| Flowers et al. | ECP+corticosteroid | TSS | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕○Moderate |

| Arai et al. | Imatinib | SCR | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕○Moderate |

| NCT02701634 | Entospletinib+corticosteroid | LSS | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Strong associationAll plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕⊕High |

| Jagasia et al. | ECP+corticosteroid+cyclosporin A/tacrolimus | TSS | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕○Moderate |

| Zeiser et al. | Ruxolitinib PO | ORR | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Strong associationAll plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕⊕High |

| Markova et al. | Ruxolitinib topical | BSA, PGA, CAILS | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Strong associationAll plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕○Moderate |

| Miklos et al. | Ibrutinib+prednisone | ORR | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | ⊕⊕⊕⊕High |

BSA: body surface area; CAILS: composite assessment of index lesion severity; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis; LSS: Lee symptom scale; ORR: overall response rate; PGA: physician's global assessment; RCT: randomized controlled trial; SCR: significant clinical response; TSS: total skin score; VSS; Vienna skin score.

Four out of 7 studies27,29,32,33 were assessed as having a moderate level of certainty due to all studies being RCTs, with downgrading primarily due to concerns around risk of bias, low effect sizes, and relatively small sample sizes. Three studies28,30,31 were assessed as having a high level of certainty due to strong effect sizes and less serious risk of bias.

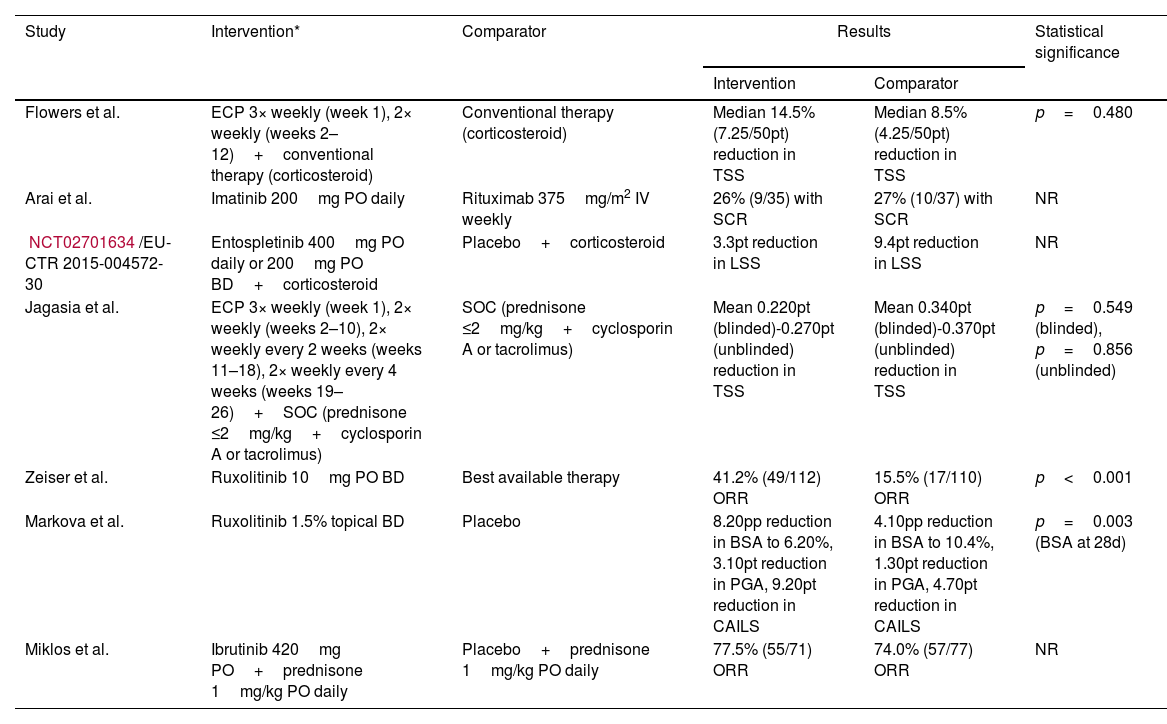

OutcomesOutcomes are shown in Table 4.

Summary of results.

| Study | Intervention* | Comparator | Results | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Comparator | ||||

| Flowers et al. | ECP 3× weekly (week 1), 2× weekly (weeks 2–12)+conventional therapy (corticosteroid) | Conventional therapy (corticosteroid) | Median 14.5% (7.25/50pt) reduction in TSS | Median 8.5% (4.25/50pt) reduction in TSS | p=0.480 |

| Arai et al. | Imatinib 200mg PO daily | Rituximab 375mg/m2 IV weekly | 26% (9/35) with SCR | 27% (10/37) with SCR | NR |

| NCT02701634/EU-CTR 2015-004572-30 | Entospletinib 400mg PO daily or 200mg PO BD+corticosteroid | Placebo+corticosteroid | 3.3pt reduction in LSS | 9.4pt reduction in LSS | NR |

| Jagasia et al. | ECP 3× weekly (week 1), 2× weekly (weeks 2–10), 2× weekly every 2 weeks (weeks 11–18), 2× weekly every 4 weeks (weeks 19–26)+SOC (prednisone ≤2mg/kg+cyclosporin A or tacrolimus) | SOC (prednisone ≤2mg/kg+cyclosporin A or tacrolimus) | Mean 0.220pt (blinded)-0.270pt (unblinded) reduction in TSS | Mean 0.340pt (blinded)-0.370pt (unblinded) reduction in TSS | p=0.549 (blinded), p=0.856 (unblinded) |

| Zeiser et al. | Ruxolitinib 10mg PO BD | Best available therapy | 41.2% (49/112) ORR | 15.5% (17/110) ORR | p<0.001 |

| Markova et al. | Ruxolitinib 1.5% topical BD | Placebo | 8.20pp reduction in BSA to 6.20%, 3.10pt reduction in PGA, 9.20pt reduction in CAILS | 4.10pp reduction in BSA to 10.4%, 1.30pt reduction in PGA, 4.70pt reduction in CAILS | p=0.003 (BSA at 28d) |

| Miklos et al. | Ibrutinib 420mg PO+prednisone 1mg/kg PO daily | Placebo+prednisone 1mg/kg PO daily | 77.5% (55/71) ORR | 74.0% (57/77) ORR | NR |

BSA: body surface area; CAILS: composite assessment of index lesion severity; ECP: extracorporeal photopheresis; LSS: Lee symptom scale; NR: not reported; ORR: overall response rate; PGA: physician's global assessment; pp: percentage point; P-ROM: photographic range of motion; pt: point; RCT: randomized controlled trial; SCR: significant clinical response; SOC: standard of care; TSS: total skin score; VSS: Vienna skin score.

Two studies reported on the ORR. Zeiser et al. reported a 41.2% (n=112) ORR with ruxolitinib versus an ORR of 15.5% (n=110) with physician-selected best available therapy. This was found to be a statistically significant difference regarding the outcomes (p<0.001).28 Miklos et al. reported an ORR of 77% (n=71) with ibrutinib plus prednisone; however, whether this differed significantly from the ORR of 74% (n=77) observed with placebo plus prednisone was not reported.30 Although Flowers et al. reported a 14.5% (n=48) reduction in TSS with ECP and standard therapy versus an 8.5% (n=47) reduction in TSS with standard therapy alone, this was not a statistically significant difference (p=0.48).33 Jagasia et al., in a different study with ECP and standard therapy, found a lesser reduction in TSS of 0.22 points (n=29) versus 0.37 points (n=24) with standard therapy alone. This difference was found to be statistically insignificant (p=0.549).32 Arai et al. reported a 26% SCR (n=35) with imatinib versus a 27% SCR (n=37) with rituximab, but did not report the statistical significance of this result.27 An unpublished clinical trial (NCT02701634) reported a 3.3 point (n=33) reduction in LSS with entospletinib and corticosteroid versus a 9.4-point (n=33) reduction on placebo. No statistical analysis was conducted as the trial was terminated before completion.31 Markova et al. reported a smaller affected BSA of 6.2% (n=24) with topical ruxolitinib versus 10.4% (n=24) with placebo at 28 days (p=.003), whereas no significant difference had been observed at baseline (p=.12).

DiscussionThis systematic review found that ruxolitinib, administered either orally or topically, is the only treatment with demonstrated efficacy for cutaneous cGVHD. Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1 and 2 (JAK1/2) inhibitor that disrupts cytokine and other inflammatory signaling pathways, thereby reducing fibrosis.34 Both studies with ruxolitinib found a statistically significant superiority in efficacy versus the best available therapy and placebo, respectively.28,29 This lends support – from an organ-specific perspective – to the New South Wales Cancer Institute guideline which notes the potential efficacy profile of ruxolitinib.35 It similarly is consistent with the U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, in which only ruxolitinib was recommended with a high level of evidence.36 A major limitation of the study by Zeiser et al.28 was the lack of blinding of both investigators and patients, which increased the risk of bias.

In contrast, the evidence in this review does not support the use of ECP for cutaneous cGVHD. Lower-level evidence cited in guidelines by the Haemato-oncology subgroup of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology and the British Society for Bone Marrow Transplantation support the use of ECP,37 as did a 2015 meta-analysis of mostly single-arm trials by Chen et al.38 However, the high-level evidence in this review found ECP non-superior to standard therapy. Indeed, the more recently published trial conducted by Jagasia et al. found a greater reduction in TSS with standard therapy alone than standard therapy plus ECP.32 Flowers et al. reported that ECP enabled 25% of patients to reduce corticosteroid dose by >50%.33 This may be relevant to the treatment of cGVHD more generally, particularly in patients with adverse reactions to corticosteroids. An important limitation of both ECP studies included in this review is that they were assessor-blinded only, owing to the nature of the intervention precluding blinding of patients.

All other agents were found to be non-beneficial in treating cutaneous cGVHD. Imatinib and ibrutinib with prednisone failed to confer significant benefit compared to standard therapy or placebo.27,30 Entospletinib, meanwhile, was markedly inferior to placebo.31

Another salient finding overall is that in all studies included in this review, the comparator arm exhibited improvement in cutaneous symptoms, even where the comparator was a placebo. This highlights firstly that the natural history of cutaneous cGVHD may still not be fully understood, and secondly, the rationale for this review including only trials with either a placebo or comparator arm with a standard/conventional therapy. Without such a comparator arm, it would not be possible to disaggregate with certainty the effect of an intervention from skin changes potentially arising as part of the natural history of cGVHD.

ImplicationsThe findings of this systematic review point to a broader dearth of high-level studies investigating treatments for cutaneous cGVHD. Despite ruxolitinib demonstrating greater efficacy than other treatments reviewed, the benefit was modest at best. The lack of efficacy demonstrated by other treatments reviewed means there remains a question of how best to treat cutaneous cGVHD in the substantial proportion of patients who do not respond to ruxolitinib.

Thus, further research into alternative therapeutic agents is needed. However, as illustrated by this review, there are two major impediments to identifying effective treatments in the current literature.

Firstly, there are currently few trials which are designed with sufficient robustness to determine the efficacy profile of treatments with a high level of certainty. For instance, although another recent systematic review by Fatoum et al.39 found the skin-specific response was highest with mesenchymal stem cells and rituximab rather than with ruxolitinib, these findings were based on single-arm clinical trials, which constitute a lower-level of evidence than the RCTs included in this review. Other trials with potentially relevant therapeutic agents that were ineligible for inclusion in this review investigated belumosudil, axatilimab, pomalidomide, and hydroxychloroquine. Belumosudil, a Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, has been approved for the management of cGVHD by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration.40,41 Both approvals were granted based on a single-arm trial by Cutler et al. which found a best ORR of 37% in skin and 71% in joints/fascia.42 Kitko et al. reported an ORR >50% achieved by all three arms of a non-controlled trial of axatilimab in which over half of patients had been refractory to treatment with ibrutinib and ruxolitinib.43 Curtis et al. found 43% of patients had a median 10% decrease in BSA affected using high or low dose pomalidomide.44 Another single-arm trial by Gilman et al. with hydroxychloroquine reported that 38% of patients had either complete or partial skin response.45

The second major gap in current literature is that even when trials are randomized and controlled, few report organ-specific outcome measures. For example, Zheng et al. reported a significantly higher response rate in patients treated with mesenchymal stem cells compared with those receiving standard therapy; however, results were not disaggregated by organ system.46 Carpenter et al. found no significant benefit from adding a calcineurin inhibitor to a prednisone and sirolimus regimen but did not report organ-specific outcomes.47 It is, therefore, recommended that future research further investigate agents ineligible for inclusion in this study to identify alternate lines of therapy. Further trials are also required to corroborate findings regarding newer therapeutic agents such as ruxolitinib. From a methodological standpoint, it is recommended that studies include a control arm and that outcome measures are disaggregated by organ-system.

Strengths and limitationsThe main limitation of this systematic review was the high degree of heterogeneity in interventions and outcome measures between studies. The inclusion/exclusion criteria used meant that of the studies eligible, only two therapeutic agents (ruxolitinib and ECP) were investigated by more than one study. A lack of a consensus around outcome measures meant that even when studies investigated the same intervention, outcome measures reported were different. This ultimately precluded meta-analysis and consequently it was not possible to establish quantitative evidence regarding treatments.

A second limitation is that this review did not differentiate between different subtypes of cutaneous cGVHD. Given the paucity of trials with skin-specific outcome measures, there were even fewer which further differentiated between the milder lichenoid and the more severe sclerodermatous subtypes. As such, the findings presented in this review are limited to cutaneous cGVHD overall.

A third limitation is that this review did not include outcome measures for safety.

The main strength of this systematic review was that only RCTs were included, which increased the level of certainty in the evidence. However, this did also curtail the number of treatments which were eligible for analysis. Another strength is that this is the first systematic review of treatments solely focused on cutaneous cGVHD.

In conclusion, this systematic review found that most therapeutic agents for which there is high-level evidence are not effective versus cutaneous cGVHD. Only ruxolitinib, which acts on a recently discovered therapeutic target, demonstrated evidence of efficacy. Therefore, further research is needed to identify alternative therapeutic agents and to validate their efficacy profile.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.