Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an acquired prothrombotic state characterized by recurrent thromboses, pregnancy loss, thrombocytopenia, and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant and/or anti-β2-glycoprotein antibody.1–3 The original clinical and laboratory criteria for APS, called the Sapporo criteria, were first published in 1999.4 These were replaced by the Sydney criteria in 2006,5 when patients were required to have at least 1 clinical criterion and 1 laboratory criterion for a diagnosis of APS to be made.

A wide variety of dermatologic manifestations have been described in patients with APS,6 including livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculitis, digital gangrene, erythematous macules,7 skin ulcerations, and, on rare occasions, extensive cutaneous necrosis.8 We report the case of a patient with widespread cutaneous necrosis as the initial manifestation of APS.

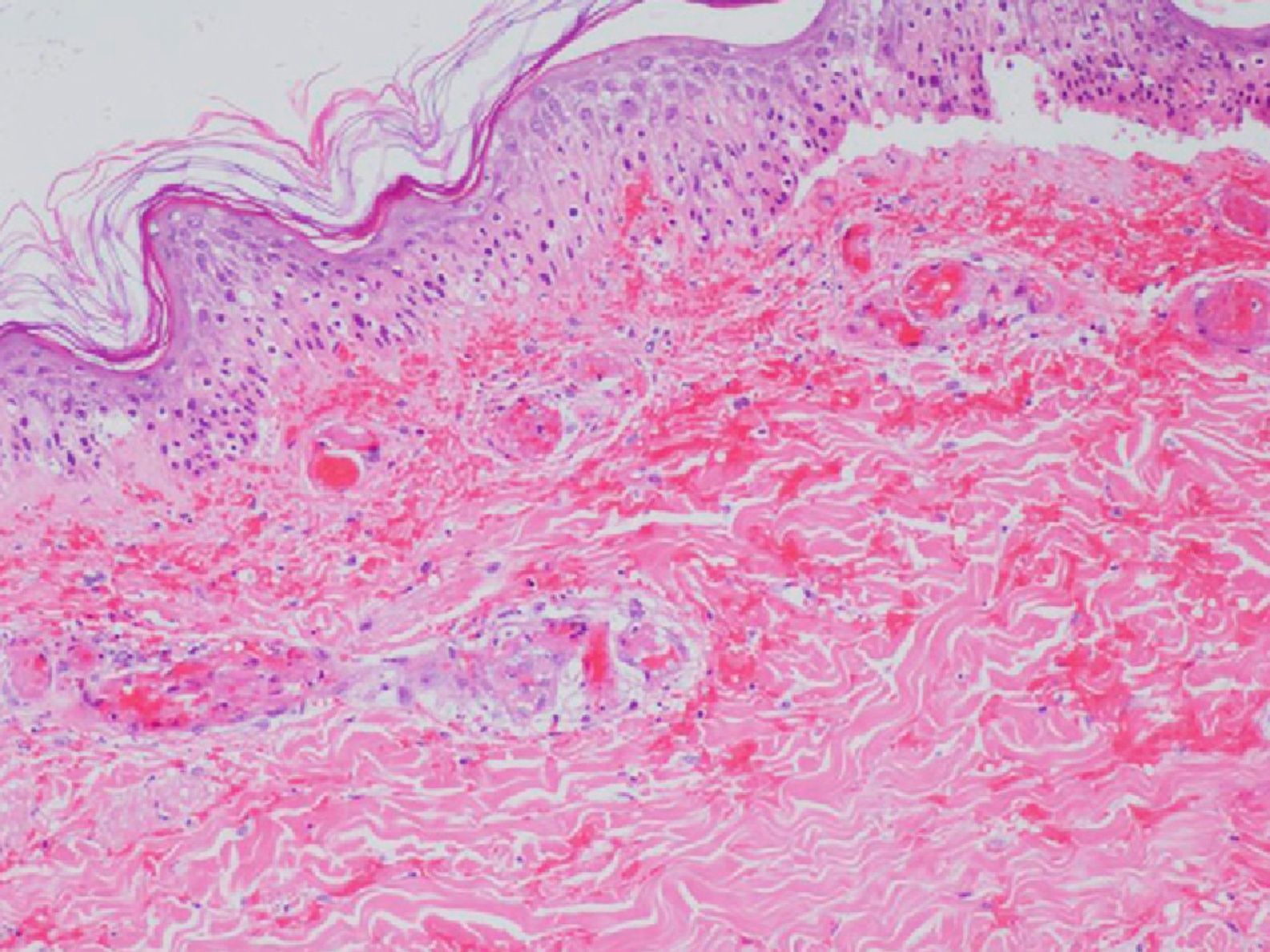

A 48-year-old woman presented at the emergency room with a 2-week history of fever, arthralgia, malaise, and chest pain. On examination she was noted to have 3 bullous erythematous violaceous plaques on her right leg (Fig. 1). Her medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Medications included thyroxine, olanzapine, risperidone, and sertraline. Laboratory tests revealed thrombocytopenia (platelet count 25,000) and normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. Lupus anticoagulant was present and the antinuclear antibody titer was 1:320. C3 and C4 levels were normal.

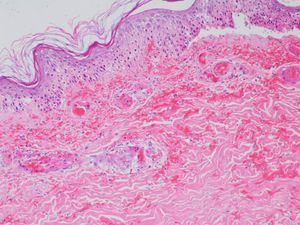

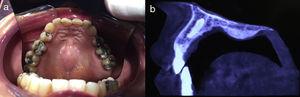

The lesions deteriorated rapidly despite initiation of corticosteroid therapy with prednisolone at a dosage of 1mg/kg/d. The dermatology service was called to evaluate the patient on day 7 of hospitalization. Examination revealed extensive cutaneous necrosis on the right leg (Fig. 2). Further laboratory data revealed an elevated anticardiolipin antibody immunoglobulin (Ig) G titer (30; normal <23). Anti-β2-glycoprotein antibody IgG levels were also elevated, but cryoglobulins and cryofibrinogens were normal. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the periphery of a lesion revealed hemorrhage throughout the dermis with organized thrombi in many dermal vessels, with no evidence of vasculitis (Fig. 3). No further lesions developed after the addition of intravenous heparin. At discharge, the heparin was replaced by long-term oral anticoagulation therapy and prednisone was tapered over 8 weeks. At the 3-month follow-up, only residual scarring remained (Fig. 4). There have been no new thrombotic events in 1 year of follow-up.

Only 23 cases of extensive cutaneous necrosis linked to APS have been reported in the literature.1,8 Most of the patients have been young women and the underlying diseases included SLE (9 cases), lupus-like disease (1 case), urinary tract infection (2 cases), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (1 case), rheumatoid arthritis (1 case), mycosis fungoides (1 case), and mixed connective tissue disease (7 cases). Seven patients had no underlying disease. All of the patients developed thrombotic complications limited to skin, and, as in our patient, the lower limbs were the most commonly affected site. Skin biopsy revealed the presence of thrombi in dermal venules and capillaries, with no evidence of vasculitis.

The mechanisms of thrombosis associated with antiphospholipid antibodies remain unknown.3 The main entities to take into consideration in the differential diagnosis are catastrophic antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Our patient achieved complete healing with prednisolone at a dose of 1mg/kg/d and heparin, which was replaced by oral anticoagulants at discharge. At the time of writing, after 1 year of follow-up, there have been no further thrombotic episodes.

We conclude that widespread cutaneous necrosis is a rare initial manifestation of APS and should be considered a major thrombotic event.3 It is important to recognize these lesions because early diagnosis enables early treatment, and, possibly, better prognosis.