Surgery is the treatment of choice for lentigo maligna (LM) and acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM). However, in these types of lentiginous melanomas, poor delineation and subclinical extension are common findings, which can lead to recurrence after incomplete excision.1

Multiple studies have shown that the 5mm margins recommended by the National Institutes of Health are insufficient. Thus, the rates of recurrence after conventional surgery can be as high as 20%.2,3

Surgery with margin control under the microscope, whether frozen or in paraffin, is the optimal type of surgery for these lesions, as it allows for lower rates of recurrence and preserves healthy tissue in functionally and aesthetically compromised locations.4

Several authors consider paraffin variants, deferred Mohs/slow Mohs, or mapped serial excision, to be the therapies of choice for melanoma.5 These techniques offer the advantage of better interpretation of atypical melanocytes at the lesion margins. However, they require longer procedures that can go on for days, during which the defect remains open until clear margins have been achieved.

One of the variants is the spaghetti technique. In its original description, it involves resecting a 2mm strip (spaghetti) at the periphery of the lesion, 3mm to 5mm away from the clinical margin. Tumor delineation can be improved with dermoscopy, Wood's light, or even confocal microscopy. The created defect is sutured directly, avoiding open wounds. The spaghetti strip is divided into several segments that are later analyzed through vertical sections along its longitudinal axis at the outer margin. This process is repeated until clear margins are obtained, at which point the central tumor is excised. The central tumor specimen is processed conventionally to identify possible invasive components.6

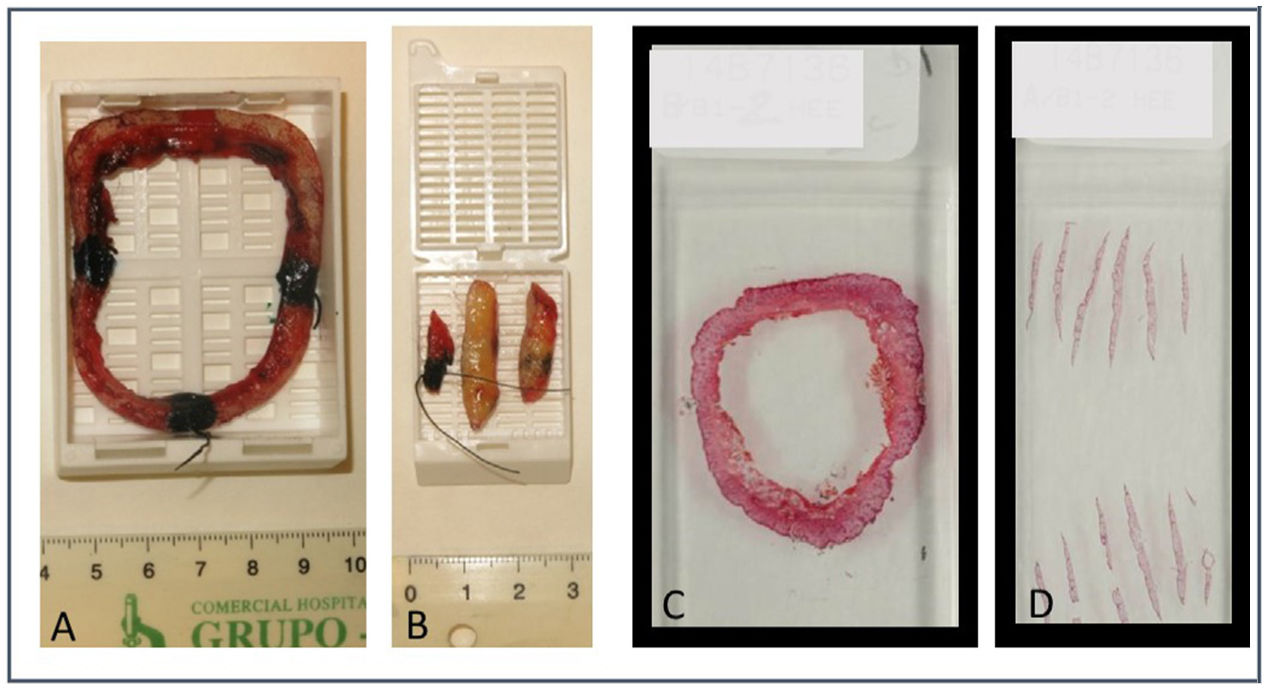

Since 2014, the spaghetti technique has been used in LM and ALM at the Dermatology Service of Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León, Spain, with some changes added compared to the initial technique: we obtain a single piece or “ring” or “ringlet” (instead of an actual spaghetti), which is incised at a 45-degree angle only on its outer margin to flatten it and make horizontal cuts. The ring is referenced on 2 different areas with sutures. The surgical bed is referenced on these same areas slightly away from the edge of the defect that will later be sutured. The pathologist immediately marks the obtained piece with colored inks only at 4 points at 12, 6, 3, and 9 o’clock positions including it as whole in a macroblock.

By processing the specimen through horizontal cuts, the pathologist still has a single ring in the macrocarrier, with a simple mapping and representation of the complete epidermis. That is how we avoid having to make and assess vertical cuts of one/several segments, saving time and facilitating the location of a possible residual tumor. In addition to evaluating 100% of the lateral margin, evaluating a portion of the deep margin has allowed us to detect a few cases of microinvasion (Figures 1 and 2).

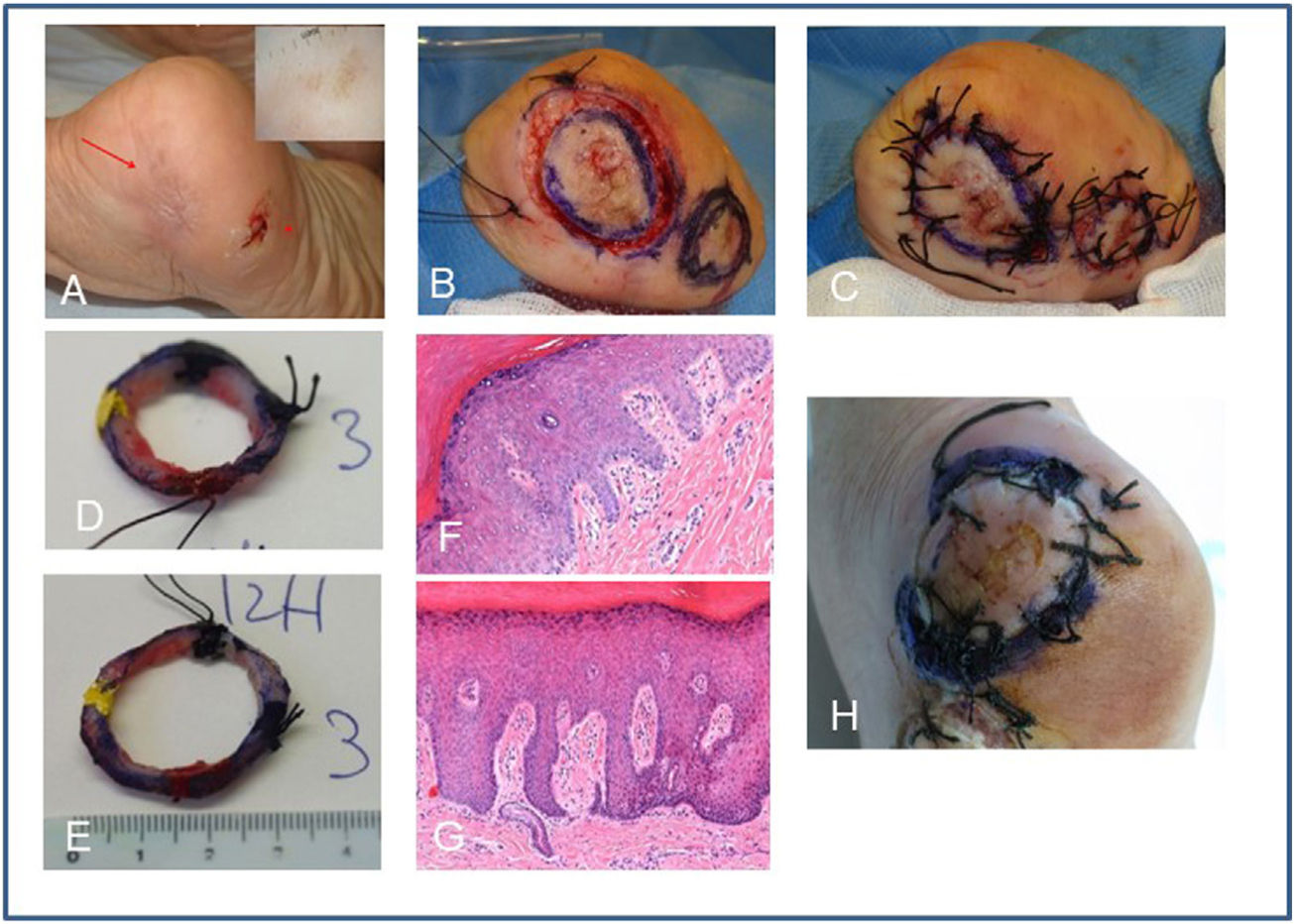

A) Recurrence of acral melanoma on the left heel confirmed by partial biopsy of in situ ALM (red arrow). Note dermoscopy with parallel ridge pattern. The image shows the scar of an adjacent excision of in situ melanoma (asterisk). B) Treatment with the spaghetti technique using the enlargement of the other completely excised adjacent in situ melanoma as negative control. Excision at 45 degrees of both spaghetti and reference at 2 points with silk. C) The defects are sutured directly. D and E) Pathologist's marking of the specimens at 12, 3, 9, and 6 positions and inclusion in macroblocks. F) Histological image (hematoxylin eosin 10x) of the 1st positive stage with atypical melanocytic hyperplasia. G) Histological image (hematoxylin eosin 10x) of the negative control. H) Performance of the second stage in positive areas at 12-1 o’clock and 6-9 o’clock positions, which turned out negative.

ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma.

Sometimes, contralateral skin is used as a negative control (Figure 1 corresponding to cases #1 and #2 of Table 1). We believe that using a negative control can be useful to help the pathologist interpret the margins of acral locations with low melanocyte density.

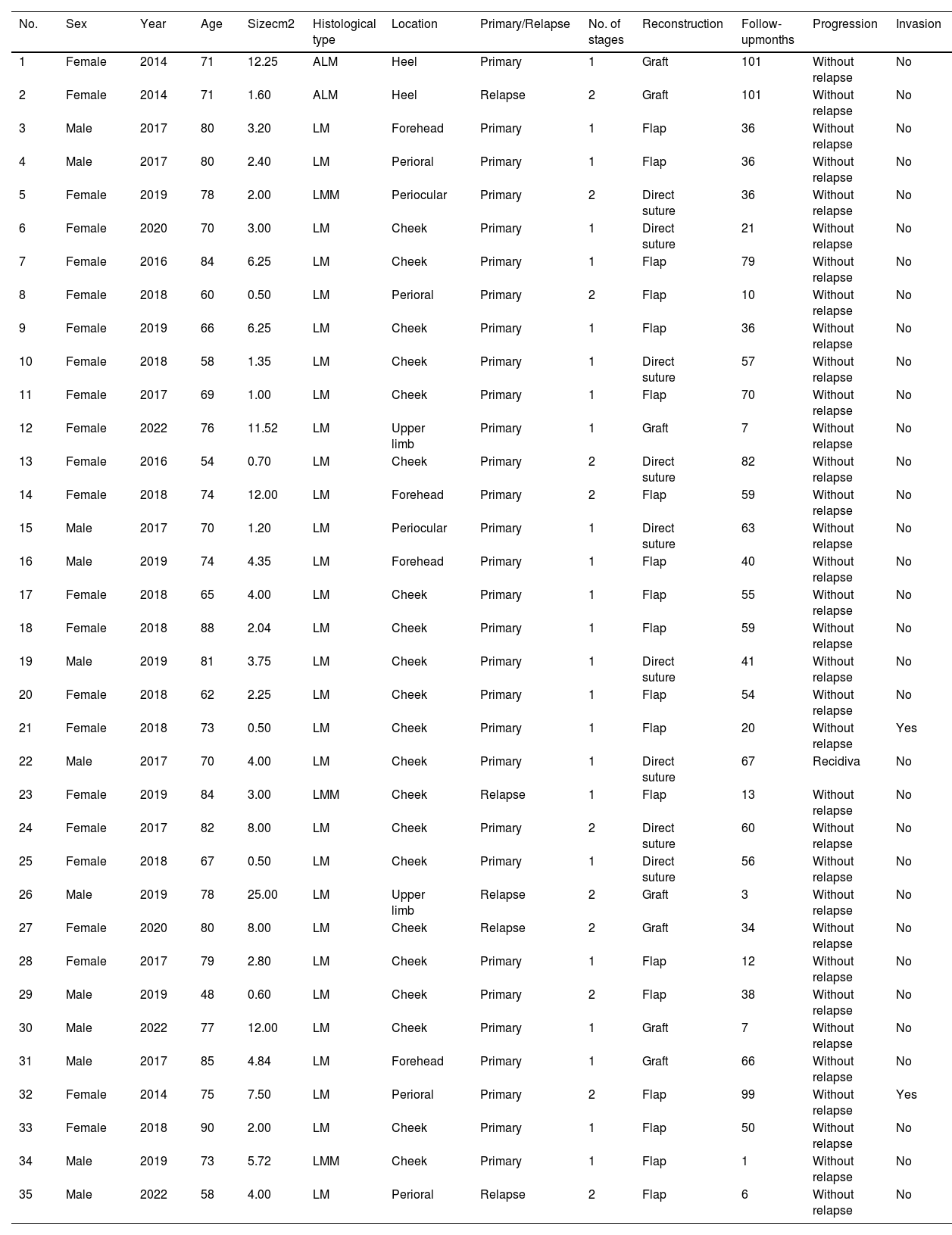

Cases of lentigo maligna and acral lentiginous melanoma treated at Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León with the modified spaghetti technique (January 2014 through December 2022).

| No. | Sex | Year | Age | Sizecm2 | Histological type | Location | Primary/Relapse | No. of stages | Reconstruction | Follow-upmonths | Progression | Invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 2014 | 71 | 12.25 | ALM | Heel | Primary | 1 | Graft | 101 | Without relapse | No |

| 2 | Female | 2014 | 71 | 1.60 | ALM | Heel | Relapse | 2 | Graft | 101 | Without relapse | No |

| 3 | Male | 2017 | 80 | 3.20 | LM | Forehead | Primary | 1 | Flap | 36 | Without relapse | No |

| 4 | Male | 2017 | 80 | 2.40 | LM | Perioral | Primary | 1 | Flap | 36 | Without relapse | No |

| 5 | Female | 2019 | 78 | 2.00 | LMM | Periocular | Primary | 2 | Direct suture | 36 | Without relapse | No |

| 6 | Female | 2020 | 70 | 3.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 21 | Without relapse | No |

| 7 | Female | 2016 | 84 | 6.25 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 79 | Without relapse | No |

| 8 | Female | 2018 | 60 | 0.50 | LM | Perioral | Primary | 2 | Flap | 10 | Without relapse | No |

| 9 | Female | 2019 | 66 | 6.25 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 36 | Without relapse | No |

| 10 | Female | 2018 | 58 | 1.35 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 57 | Without relapse | No |

| 11 | Female | 2017 | 69 | 1.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 70 | Without relapse | No |

| 12 | Female | 2022 | 76 | 11.52 | LM | Upper limb | Primary | 1 | Graft | 7 | Without relapse | No |

| 13 | Female | 2016 | 54 | 0.70 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 2 | Direct suture | 82 | Without relapse | No |

| 14 | Female | 2018 | 74 | 12.00 | LM | Forehead | Primary | 2 | Flap | 59 | Without relapse | No |

| 15 | Male | 2017 | 70 | 1.20 | LM | Periocular | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 63 | Without relapse | No |

| 16 | Male | 2019 | 74 | 4.35 | LM | Forehead | Primary | 1 | Flap | 40 | Without relapse | No |

| 17 | Female | 2018 | 65 | 4.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 55 | Without relapse | No |

| 18 | Female | 2018 | 88 | 2.04 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 59 | Without relapse | No |

| 19 | Male | 2019 | 81 | 3.75 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 41 | Without relapse | No |

| 20 | Female | 2018 | 62 | 2.25 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 54 | Without relapse | No |

| 21 | Female | 2018 | 73 | 0.50 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 20 | Without relapse | Yes |

| 22 | Male | 2017 | 70 | 4.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 67 | Recidiva | No |

| 23 | Female | 2019 | 84 | 3.00 | LMM | Cheek | Relapse | 1 | Flap | 13 | Without relapse | No |

| 24 | Female | 2017 | 82 | 8.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 2 | Direct suture | 60 | Without relapse | No |

| 25 | Female | 2018 | 67 | 0.50 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Direct suture | 56 | Without relapse | No |

| 26 | Male | 2019 | 78 | 25.00 | LM | Upper limb | Relapse | 2 | Graft | 3 | Without relapse | No |

| 27 | Female | 2020 | 80 | 8.00 | LM | Cheek | Relapse | 2 | Graft | 34 | Without relapse | No |

| 28 | Female | 2017 | 79 | 2.80 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 12 | Without relapse | No |

| 29 | Male | 2019 | 48 | 0.60 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 2 | Flap | 38 | Without relapse | No |

| 30 | Male | 2022 | 77 | 12.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Graft | 7 | Without relapse | No |

| 31 | Male | 2017 | 85 | 4.84 | LM | Forehead | Primary | 1 | Graft | 66 | Without relapse | No |

| 32 | Female | 2014 | 75 | 7.50 | LM | Perioral | Primary | 2 | Flap | 99 | Without relapse | Yes |

| 33 | Female | 2018 | 90 | 2.00 | LM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 50 | Without relapse | No |

| 34 | Male | 2019 | 73 | 5.72 | LMM | Cheek | Primary | 1 | Flap | 1 | Without relapse | No |

| 35 | Male | 2022 | 58 | 4.00 | LM | Perioral | Relapse | 2 | Flap | 6 | Without relapse | No |

ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; LM, lentigo maligna; LMM, minimally invasive lentigo maligna melanoma.

Size: clinical size of the lesion in cm2.

Histological type: histological type after initial biopsy.

Primary vs relapse after previous treatments.

Follow-up in months.

Invasion: identification of invasive component in the analysis of the central tumor specimen.

Year: year of intervention.

We conducted a retrospective and observational study on LM and ALM treated at our center with the modified spaghetti technique from January 2014 through December 2022. During this period, a total of 35 lesions in 33 patients were treated. Twenty-two patients were women (66.7%). The median age of the patients was 74 years (range, 48-90), 33 lesions were LM and 2, ALM. A total of 5 cases (14.3%) were recurrences after previous treatment, and 3 were minimally invasive lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) in the initial biopsy. A total of 31 tumors (85.7%) were located on the face, 21 of which were on the cheek (60%). The median clinical size was 3.2cm2 (range, 0.5-25). In 11 cases (31.4%), 2 passes were necessary to obtain clear margins. Overall, 70% of final defect reconstructions were performed using grafts or flaps. An invasive LMM component was detected in 2 cases after conventional analysis of the central specimen. After a median follow-up of 41 months (range, 1-101), the rate of tumor control was 97.1%, with only 1 recurrence (2.9%) being reported at the 60-month follow-up (Table 1).

Unlike others which are performed later, the spaghetti technique has the advantage of not leaving an open wound during successive stages, which reduces the risk of infection and patient discomfort, simplifies care, avoids hospital stays, and can be performed outpatiently.

However, being a deferred technique means that it requires multiple patient visits to complete the stages required for excision, and that tumor analysis could be delayed for days or even weeks. Sometimes, this analysis may reveal an invasive component, as it occurred in 2 of our cases. This finding is present in 9% of the lesions initially diagnosed as LM via partial biopsy.7 The presence of an invasive component can be anticipated if the histopathological examination of the initial biopsy shows melanocytes forming rows or an artifact groove, especially if > 25% of melanocytes are forming nests, pagetoid extension, and a prominent inflammatory infiltrate. Also, if dermoscopy reveals the presence of irregular spots, obliterated follicular openings and black color, or more than 5 colors, pigmented and erythematous rhomboidal structures added to the aforementioned follicular obliteration.5,8–10

In contrast, flash freezing of conventional Mohs surgery to treat LM/ALM would have the advantage of shortening the entire process to just 1 day, using rapid immunohistochemical staining techniques to address margin interpretation issues.5 However, flash freezing of conventional Mohs surgery requires specific infrastructure that is not always available in all the centers. In addition, it requires trained personnel (dermatologic surgeon, pathologist, and technician). Additionally, the immunohistochemical stains used cannot distinguish malignant from benign melanocytes.

For all these reasons, we believe that the spaghetti technique has several advantages that make it feasible for most centers. In our experience, the change made simplifies the procedure by saving time with the examination of a single sample without losing complete margin evaluation.

Our series lacks long-term follow-up, and the rate of recurrence is similar to the one reported in the original technique and subsequent series. Longer follow-up studies would be necessary, though, as recurrences, if they occur, tend to be slow and late. We wish to emphasize that this is a simple technique that, unlike conventional Mohs surgery, does not require any special infrastructure, except for macrocarriers, or specific training.

FundingThis study has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.