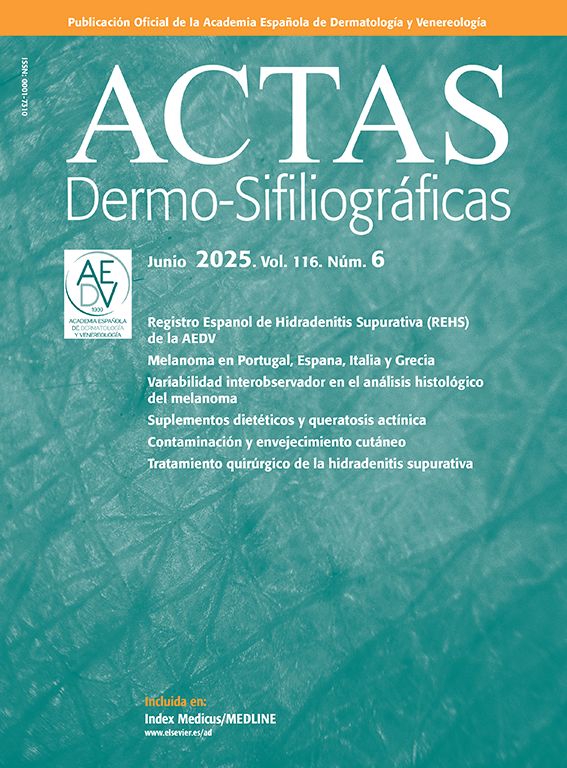

A woman of African origin, aged 59 years, attended the clinic with pruriginous lesions of 1 year standing, with involvement of the trunk and genital region. She had undergone kidney transplantation 6 years earlier and received immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus, prednisone, and mycophenolate mofetil. The physical examination revealed multiple flat papules with a pale pink color, measuring 2 to 3mm, distributed symmetrically in the inframammary folds, as well as in the inguinal, vulvar, and perineal region (Fig. 1A and B). Some of these lesions were grouped linearly (Koebner phenomenon). Histopathological study showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis with marked hypergranulosis, and enlarged keratinocytes with pale blue-gray cytoplasm in the granular layer (Fig. 1C and D). Based on these findings, the age of onset of the clinical manifestations, and the chronic immunosuppression of the patient, acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) was diagnosed.

A, Flat rose-colored papules in the inframammary folds, some with a linear pattern (Koebner phenomenon). B, Detail of the lesions in the inframammary folds. C, Similar lesions in the vulvar region, reminiscent of flat warts. D and E, (Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40 and ×100, respectively), sample of skin biopsy taken from the inframammary region that shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and increased keratinocytes with a pale blue-gray cytoplasm, histopathological findings considered pathognomonic of the cytopathic effects of HPV.

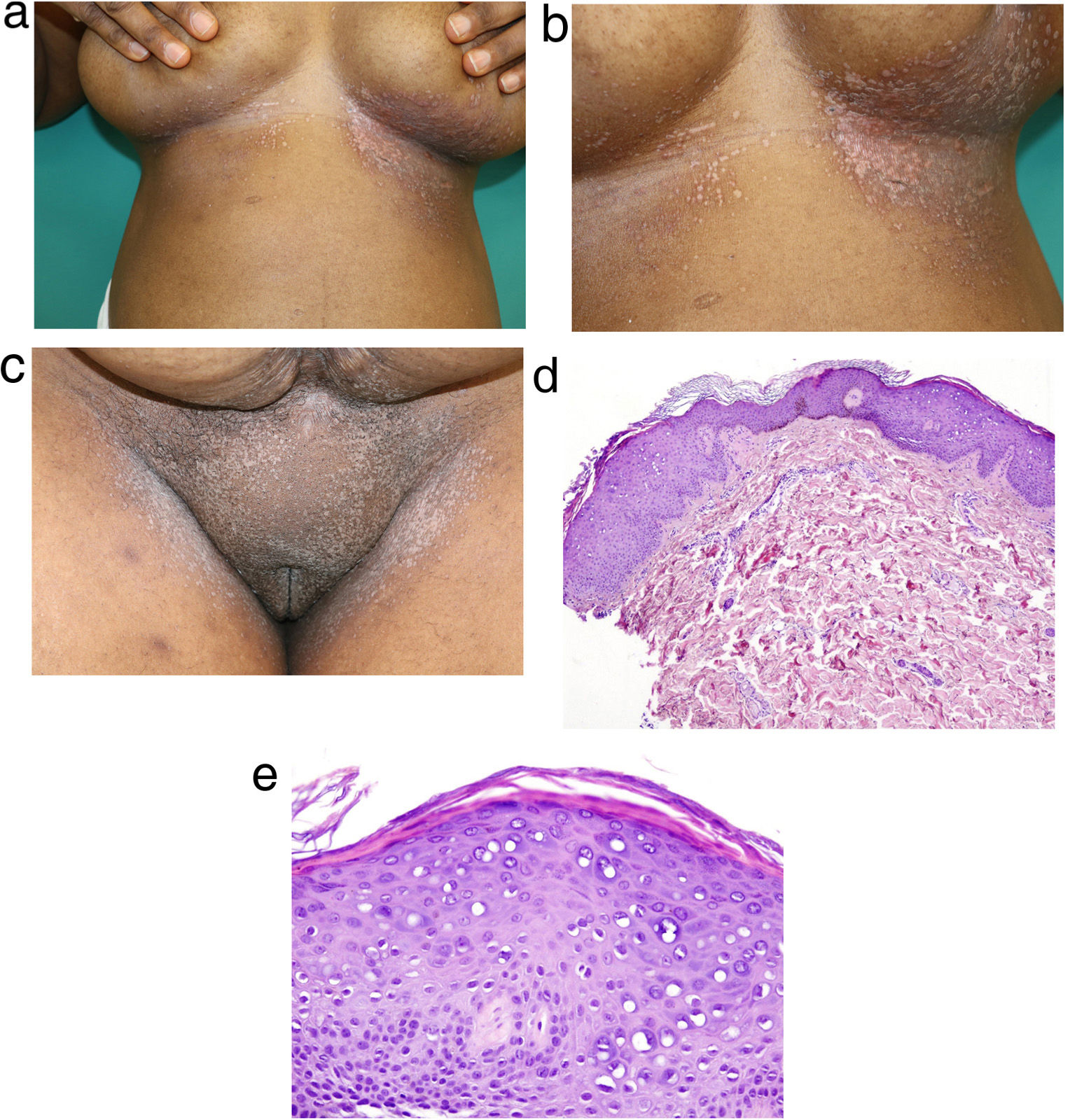

Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient. Given that these skin lesions were symptomatic and that the affected areas were prone to irritation and pain, topical therapies such as imiquimod and tretinoin were not considered suitable. In light of a case report,1 the nonavalent HPV vaccine (genotypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58) was prescribed (vaccine administration at 0, 2 and 6 months). Two weeks after the first dose, the patient experienced complete relief from pruritus and an improvement in the cutaneous lesions. Three months after the third dose, the skin lesions had completely resolved (Fig. 2A and B). After 6 months of follow-up, the patient continued in remission.

EV is an uncommon skin disease characterized by greater sensitivity to certain beta human papilloma viruses (HPV), with HPV 5 and 8 being the genotypes most frequently associated with this condition.2 EV is an autosomal recessive disease associated with mutations in the EVER1 and EVER2 genes (classic genetic EV). Recently, other genes such as RHOH, MST-1, CORRO1A, and EC1 (nonclassic genetic EV) have also been implicated.3 The term acquired EV describes a syndrome similar to EV associated with acquired cellular immunodeficiency, especially when associated with immunosuppressive therapy in solid organ transplant recipients or in patients with HIV infection. The acquired form has also been reported in association with systemic lupus erythematosus, lymphomas, and specific immunosuppressive drugs.2,4

Clinical and histological manifestations are similar both in genetic and acquired EV.5 Clinically, this condition presents in the form of versicolor pityriasis-like scaly macules and flat papules that are reminiscent of flat verrucae. Both genetic and acquired EV are characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and superficial keratinocytes with pale blue-grey cytoplasm, a finding considered pathognomonic of the cytopathic effects of HPV.6

In classic genetic EV, the lesions present a risk of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma (30% to 60% of cases).2 Although the risk of malignancy in nonclassic genetic EV and in acquired EV is not known, these lesions should be closely monitored. In addition, the risk of dysplasia could be greater in immunodepressed patients, given the combined effect of immunodepression and the oncogenic potential of HPV-5 and HPV-8.

Treatment for acquired EV is currently not standardized and relapse on suspending treatment is common. The treatments used to date, with variable success rates, include topical imiquimod 5%, glycolic acid 15%, and topical and oral retinoids.5 In the case presented, it was decided to administer the HPV vaccine given the good response reported in the literature,1 although our patient was not given concomitant treatments for the lesions.

One of the main limitations in the present case is that our laboratory does not have gene sequencing capability; however, the clinical and histological findings were consistent with the diagnosis of acquired EV. With the growing number of patients who receive immunosuppressive therapies, the incidence of acquired EV is likely to increase. Our case highlights the importance of recognizing this entity clinically and describing cutaneous manifestations in patients with dark skins. Appropriate management is essential, given the impact of the disease on quality of life and its prognostic implications, especially the potentially higher risk of malignant transformation in immunodepressed individuals.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of InterestM. Munera-Campos has received fees for scientific consulting, presentations, and other activities from Abbvie, LEO Pharma, Janssen, Sanofi, and Galderma, and has participated as the principal investigator and subinvestigator in clinical trials with Lilly, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, Almirall, UCB, and Galderma.

J.M. Carrascosa has participated as principal/subinvestigator and/or received fees as a speaker and/or steering committee for AbbVie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer ingelheim, Biogen, and UCB.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.