The clinical presentations of Lipoatrophia semicircularis (LS) vary, and diagnostic criteria are unclear. Several etiopathogenic factors, including occupational environmental ones, have been suggested. We aimed to describe a cluster of cases of suspected LS that started to appear in May 2008 among employees of the city council of Madrid, Spain. We report the actions taken by the council’s Occupational Health Service and propose clinical categories with prognostic implications.

Material and methodRetrospective observational case series study including prospectively collected data from patients evaluated between 2008 and 2021 at the Madrid City Council STI/Dermatology Department. Information on measures taken by the Occupational Health Service is detailed. The recording of clinical variables for statistical analysis and the proposal of defined clinical patterns were carried out.

ResultsWe studied the cases of 75 women and one man, most of whom attended follow-up visits for a median of 37 months. Local symptoms were observed in just 14.5% of patients. The cases were classified into 4 groups: typical LS, unilateral LS, band-like lipoatrophy in the lower limbs, and nonspecific LS. Clinical outcomes were more often favorable in the first 2 groups, in which 76% of patients achieved total or partial improvement of lesions (vs. 25.8% in the last 2 groups). LS was negatively associated with the presence of hypertrophic subcutaneous adipose tissue (P < .001).

DiscussionTypical LS, which can often be unilateral, generally has a satisfactory outcome. The clinical characteristics of this form distinguish it from other types of lipoatrophy. Measures taken by the Occupational Health Service contributed to favorable outcomes. In this series, LS was not associated with marked subcutaneous adipose tissue hypertrophy in the thighs. Our proposed categories may help distinguish between cases of LS with a favorable prognosis and other cases presenting with skin surface depressions, which are often persistent.

La lipoatrofia semicircular (LS) puede tener presentaciones clínicas variadas, sin criterios diagnósticos claros. Se han propuesto varios factores etiopatogénicos, incluyendo determinados ambientes laborales. En este manuscrito se pretende describir las características de un brote de casos sospechosos de LS que se inició en mayo de 2008 entre trabajadores del Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Con base en la experiencia acumulada, se describen las acciones realizadas por el Servicio de Salud Laboral y se proponen unos criterios clínicos con implicación pronóstica que permitan categorizar los casos.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional retrospectivo tipo serie de casos que incluye datos recogidos de forma prospectiva de los pacientes revisados en el Servicio de ITS/Dermatología del Ayuntamiento Madrid entre 2008 y 2021. Se lleva a cabo la descripción de las medidas realizadas desde Salud Laboral. A través del registro y análisis estadístico de las variables recogidas durante la evaluación clínica de los pacientes, se proponen unos patrones clínicos definidos.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 75 mujeres y un hombre, seguidas en su mayoría durante un período con mediana de 37 meses. Los síntomas locales fueron poco frecuentes (14,5%). Se propone la clasificación de las pacientes en 4 grupos: LS típica, LS unilateral, lipoatrofia en banda en miembros inferiores y lipoatrofia inespecífica. Al comparar los 2 primeros grupos con los 2 últimos, pudo constatarse una evolución clínica más favorable (76 versus 25,8% de mejoría total o parcial de las lesiones), además de una asociación negativa con la presencia de hipertrofia del tejido subcutáneo (p < 0,001).

DiscusiónLa LS típica (que puede ser frecuentemente unilateral) tiene por lo general una evolución favorable y unas características definidas que permiten diferenciarla de otros cuadros de lipoatrofia. Las medidas descritas realizadas por el Servicio de Salud Laboral contribuyeron a dicha evolución. En nuestra serie la LS no se asoció a la presencia de hipertrofia grasa de la región de los muslos. Los criterios de clasificación propuestos permiten a priori diferenciar los casos de LS (con una probable evolución favorable) de otros en forma de depresiones de la superficie cutánea que en muchos casos son persistentes.

Lipoatrophia semicircularis (LS) was described in 1974 by Gschwandtner and Münzberger1, and is characterized by depressed areas on the skin surface with a peculiar distribution in long, horizontal, generally symmetric bands located on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the thighs. It predominantly affects young women. This diagnosis has, however, included cases in which the lesions presented unilaterally, in different locations2, or with a presentation in the form of several parallel bands3, and this can lead to the lesions being confused with normal variations in the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue, which appear as depressions or indentations in the skin surface4. Diagnosis is essentially clinical and no additional tests have been reported that help to confirm the diagnosis.

Suggested causes include repetitive pressure on specific areas due to contact with the edge of a desk or chair3, or if an incorrect work posture is used5. It has also been described in association with the pressure exerted by different garments6–8 and with repeated microtrauma9,10.

Although isolated cases have been published, groups of cases supposedly linked to a specific work environment have also been reported, in the form of “epidemics”11 in people with sedentary office jobs. These outbreaks have been linked to work with computers, especially spending long periods in buildings with climate control and little natural ventilation (so-called intelligent buildings)12. Some authors have suggested that exposure to electric currents or electromagnetic fields produced by computers or their cables, especially if this occurs in an environment with low relative humidity, may be the cause that triggers the observed lesions.

In the literature published to date, we have found no uniform diagnostic criteria that make it possible to differentiate between cases of LS and other lesions of depressed areas of the skin surface.

In May 2008, an outbreak of suspected cases of LS occurred among the administrative personnel of several buildings belonging to Madrid City Council, which required the intervention of the city council’s occupational health service, with the collaboration of the dermatology service, in investigating the cases.

The primary objective of this study is to describe the clinical presentation and course of the lesions assessed in the dermatology department. Secondary objectives, based on the experience accumulated, are to describe the actions carried out by the aforementioned occupational health department and to propose clinical criteria with prognostic implications that may make it possible to categorize cases.

Material and MethodsWe performed a retrospective observational case-series study that included data collected prospectively from patients seen at the STI/Dermatology Service of Madrid City Council between May 2008 and March 2021.

From the moment the appearance of LS in some employees of different areas of Madrid City Council and its autonomous bodies, the subdirectorate of occupational risk prevention, through the department of occupational health, drew up an action protocol aimed at studying and assessing the situation. Similarly, the technical teams of the subdirectorate carried out a number of actions at the affected workplaces to determine the possible causes of these cases. The application of this protocol in the event of a suspected case involved notifying the department of occupational health of the potential case, followed by a specific medical examination, an examination by the city council’s dermatology specialist, and reporting of the case to the corresponding subdirectorate. Once the case had been confirmed and the subdirectorate notified, the following were performed for each patient: study of the workplace, hygiene survey of the worker and measurement of the agents that may have caused the LS (temperature and humidity conditions, electrostatic charge on furniture and people, surface resistivity, and electromagnetic fields).

Thus, all patients included in the series were clinically assessed by a specialist in medical-surgical dermatology and venereology (FJBG), who recorded the clinical variables and created a photographic record of the lesions (this record was repeated in each examination). Follow-up was initially recommended between 3 and 6 months after the initial assessment and, once stability and lack of local symptoms had been established, annual follow-up was recommended until the end of the study or until the lesions disappeared.

The following clinical variables were recorded: location and morphological description of the lesions and their measurements; intensity of the lesions in 3 levels (manifest [clearly visible], moderate [barely visible but clearly noticeable on palpation], and mild [noticeable only on palpation]); and level of hypertrophy of the subcutaneous cellular tissue in the region of the thighs (high, moderate, or absent). The study of the clinical characteristics of the case made it possible to group them into a proposed case classification.

The variables are expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. The EpiInfo® (version 7.2.2.6) software package was used to analyze the data, using the χ2 test to detect associations between qualitative variables (the degree of association is expressed using the odds ratio) and the Mann–Whitney U test for comparison of means.

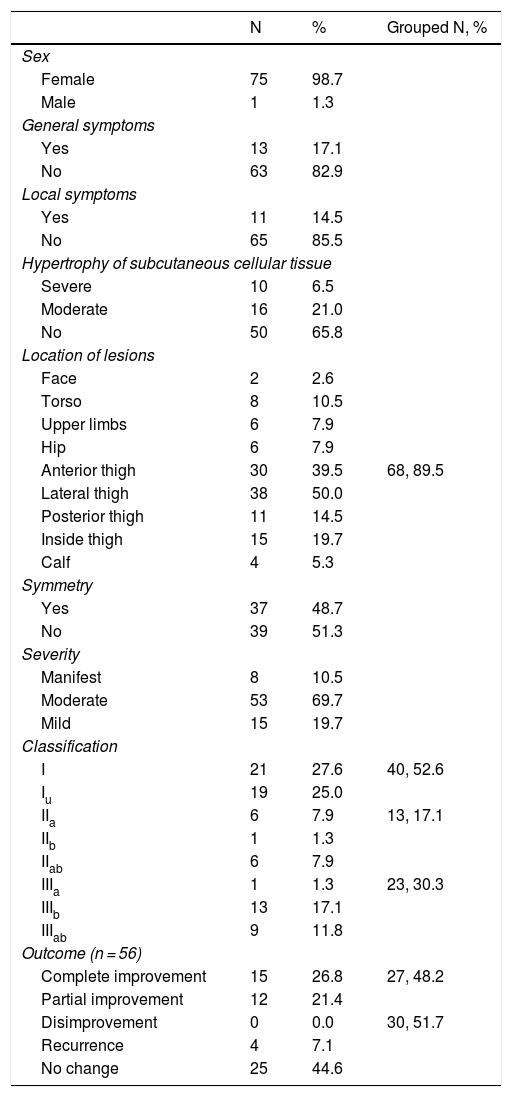

ResultsA total of 75 women and 1 man were enrolled in the study. The clinical characteristics of the cases and the distribution of the lesions are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the recorded patients and lesions.

| N | % | Grouped N, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 75 | 98.7 | |

| Male | 1 | 1.3 | |

| General symptoms | |||

| Yes | 13 | 17.1 | |

| No | 63 | 82.9 | |

| Local symptoms | |||

| Yes | 11 | 14.5 | |

| No | 65 | 85.5 | |

| Hypertrophy of subcutaneous cellular tissue | |||

| Severe | 10 | 6.5 | |

| Moderate | 16 | 21.0 | |

| No | 50 | 65.8 | |

| Location of lesions | |||

| Face | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Torso | 8 | 10.5 | |

| Upper limbs | 6 | 7.9 | |

| Hip | 6 | 7.9 | |

| Anterior thigh | 30 | 39.5 | 68, 89.5 |

| Lateral thigh | 38 | 50.0 | |

| Posterior thigh | 11 | 14.5 | |

| Inside thigh | 15 | 19.7 | |

| Calf | 4 | 5.3 | |

| Symmetry | |||

| Yes | 37 | 48.7 | |

| No | 39 | 51.3 | |

| Severity | |||

| Manifest | 8 | 10.5 | |

| Moderate | 53 | 69.7 | |

| Mild | 15 | 19.7 | |

| Classification | |||

| I | 21 | 27.6 | 40, 52.6 |

| Iu | 19 | 25.0 | |

| IIa | 6 | 7.9 | 13, 17.1 |

| IIb | 1 | 1.3 | |

| IIab | 6 | 7.9 | |

| IIIa | 1 | 1.3 | 23, 30.3 |

| IIIb | 13 | 17.1 | |

| IIIab | 9 | 11.8 | |

| Outcome (n = 56) | |||

| Complete improvement | 15 | 26.8 | 27, 48.2 |

| Partial improvement | 12 | 21.4 | |

| Disimprovement | 0 | 0.0 | 30, 51.7 |

| Recurrence | 4 | 7.1 | |

| No change | 25 | 44.6 | |

The median time for development of the lesions, self-reported by the patients before their first assessment was 2.5 months (range, 1–48 mo). We were able to monitor the course of 56 of the patients (73.7%) who came for in-person follow-up examinations: the mean follow-up time in these cases was 48.4 months (range, 7–135 mo); median, 37 mo).

Local symptoms were recorded in 11 cases (14.5%), mainly described as heavy and tired legs (9 patients) and paresthesia (2). General symptoms were reported by 13 patients (17.1%): asthenia (7 cases), myalgia (5), and headache (2).

After the actions taken by the Department of Occupational Health, the following preventive measures were implemented:

- -

Maintain relative humidity in the workplaces between 45% and 55%, regardless of the amount of outside air entering the space.

- -

Apply antistatic products to surfaces prone to holding static-electric charges (chairs, desks, etc.) in the form of spray or varnish.

- -

Apply antistatic product daily when cleaning the floor to help dissipate any static charges that are generated and accumulate.

- -

Inform personnel about static electricity and the factors that may affect it and on individual actions to prevent it:

- •

Adjust chair height to prevent thighs from entering into contact with desks, resting feet on the floor or on the footrest.

- •

Adopt an upright position, with forearms resting on the armrests or on the desk, in a manner appropriate for the work activity in question.

- •

Avoid leaning repeatedly on the edge of the desks.

- •

Stand up and walk a few steps at least once every hour.

- •

Do not rest feet on the legs of the chair.

- •

Avoid repeated rubbing against the chair during the working day.

- •

Sit with the back supported by the backrest of the chair as much as possible.

- •

Do not use fabrics with artificial (acrylic) fibers when the accumulation of static electricity is considerable.

- •

Avoid using rubber-soled footwear.

- •

Avoid dragging the feet when walking.

- •

Do not lean thighs against the edges of desks, drawer units or auxiliary tables.

- •

Stay hydrated by drinking water.

- •

Avoid the use of very tight clothing as much as possible.

- •

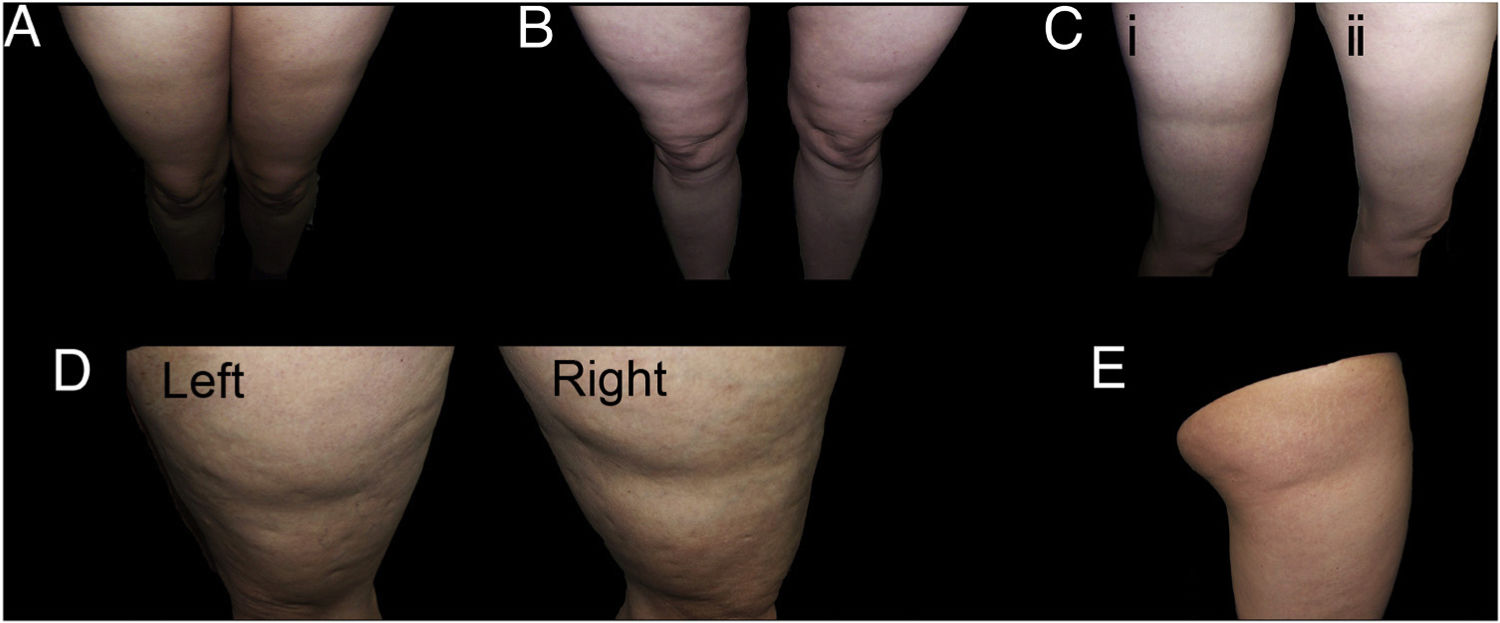

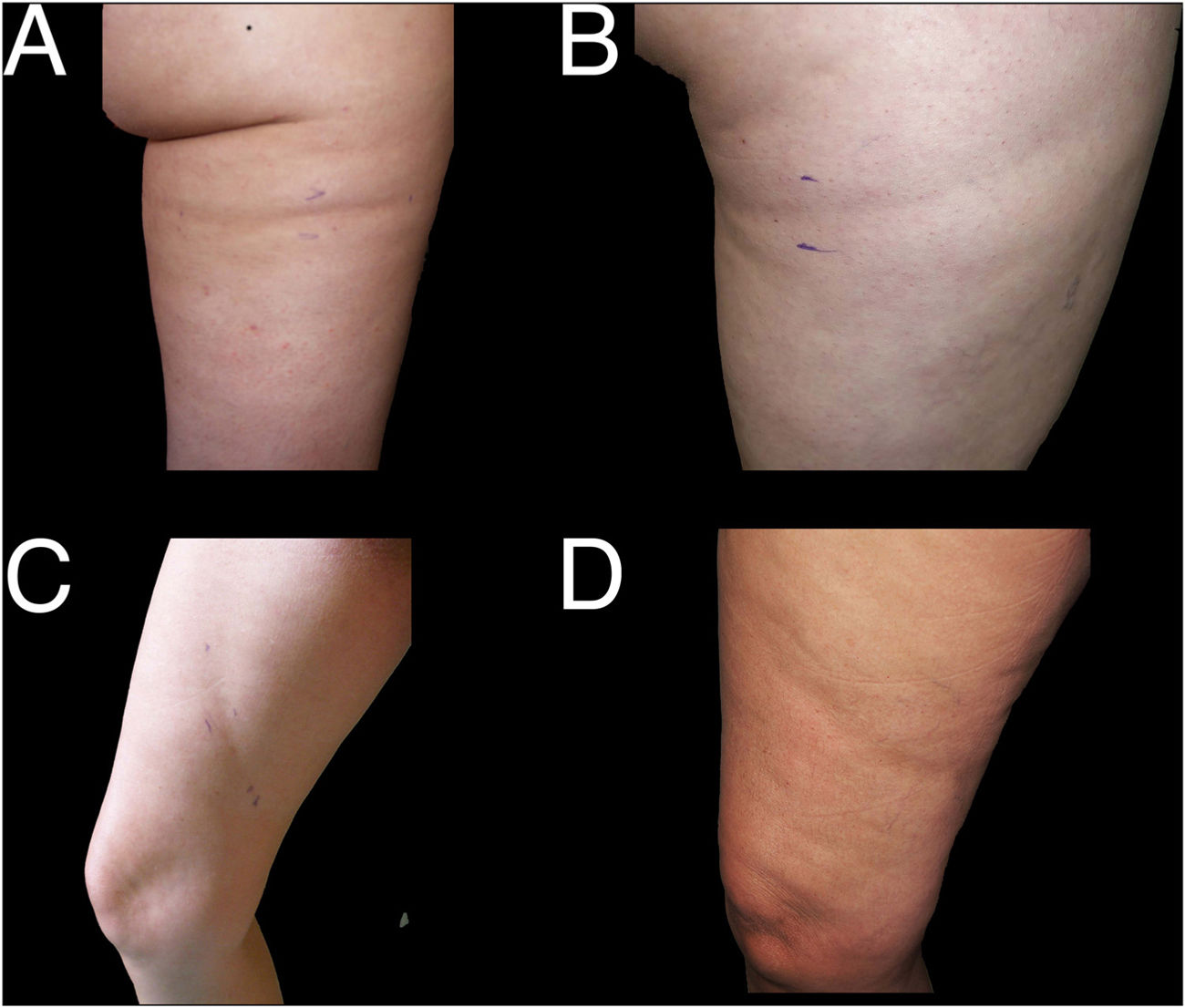

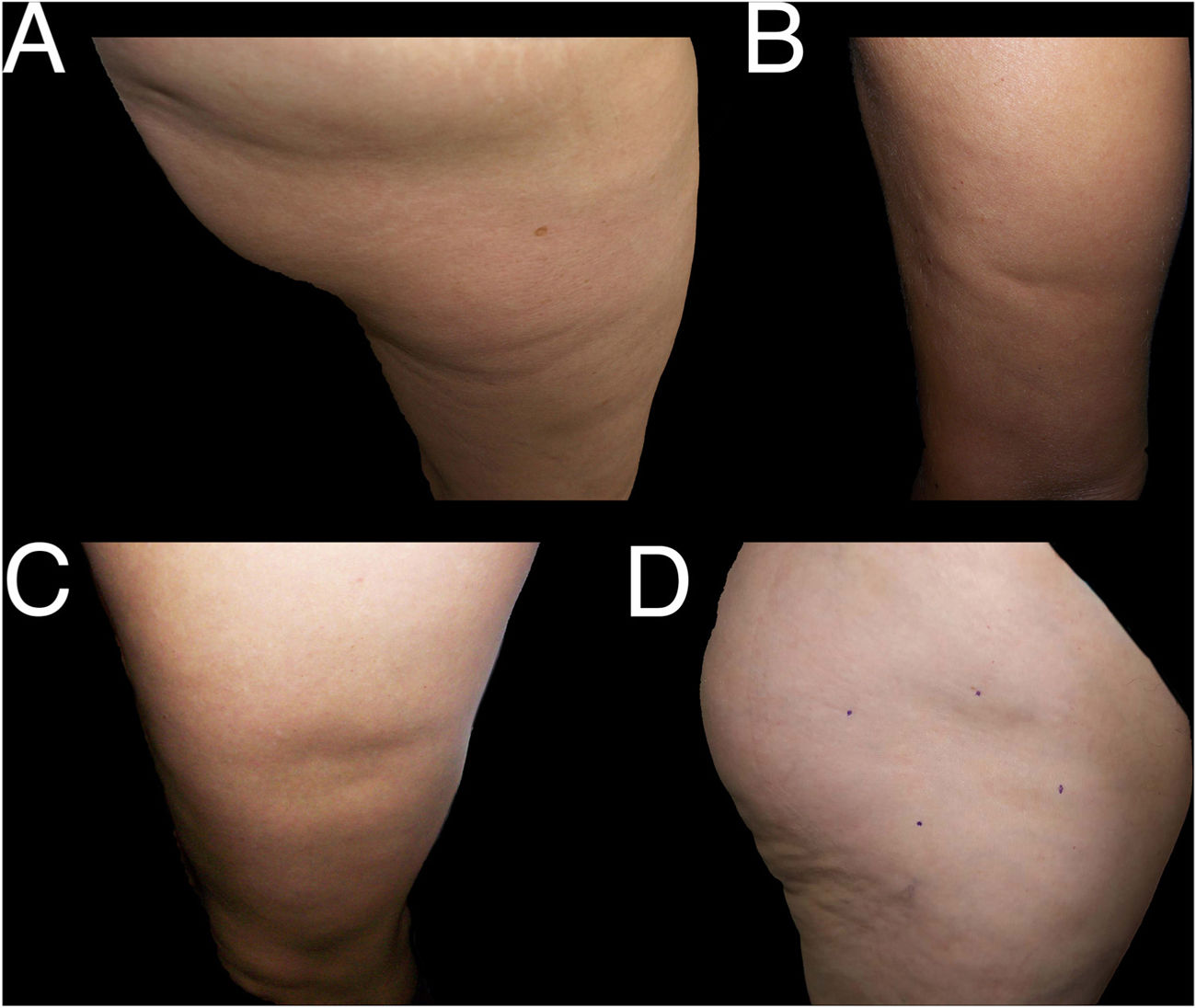

With regard to the dermatologic examination, Table 2 shows our proposed classification and criteria for identifying the cases of LS (Fig. 1) and differentiating them from other lesions with depressed skin surface (Figs. 2 and 3).

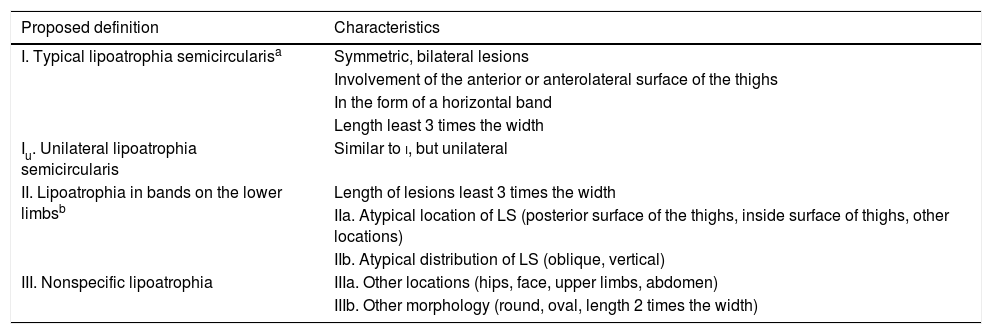

Diagnostic criteria. Proposed classification of lipoatrophia lesions.

| Proposed definition | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I. Typical lipoatrophia semicircularisa | Symmetric, bilateral lesions |

| Involvement of the anterior or anterolateral surface of the thighs | |

| In the form of a horizontal band | |

| Length least 3 times the width | |

| Iu. Unilateral lipoatrophia semicircularis | Similar to i, but unilateral |

| II. Lipoatrophia in bands on the lower limbsb | Length of lesions least 3 times the width |

| IIa. Atypical location of LS (posterior surface of the thighs, inside surface of thighs, other locations) | |

| IIb. Atypical distribution of LS (oblique, vertical) | |

| III. Nonspecific lipoatrophia | IIIa. Other locations (hips, face, upper limbs, abdomen) |

| IIIb. Other morphology (round, oval, length 2 times the width) |

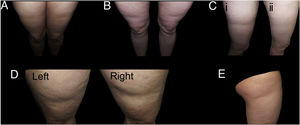

Examples of cases of typical lipoatrophia semicircularis (LS) (Group I). A and B, LS with bilateral, symmetric distribution in bands on the anterior surface of the thighs. C, Bilateral and symmetric LS (only one of the thighs is shown in the figure) on the outside surface of the thigs (i), with spontaneous resolution after a year (ii). D, LS in bands on the outside surface of both thighs, reasonably symmetric. E, Unilateral LS on the outside surface of the right thigh (Group iu).

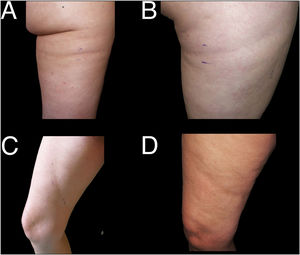

Examples of cases of nonspecific lipoatrophia (Group III). A and B, lipoatrophia in other locations (Group iiia): on the buttock (A) and on the posterior surface of the arm (B). C and D, lipoatrophia with other morphologies (Group iiib): lipoatrophia with an almost oval form on the outside surface of the left thigh (C) and lipoatrophia with a round-oval form in the anterolateral region of the proximal third of the right thigh (D).

Considering the grouped form of the cases included in categories i and iu (i.e., those that show the characteristics most widely recognized as typical of LS) and comparing them with the rest, the following were observed:

- -

No significant differences existed between the 2 groups in terms of mean follow-up time (47.1 months for patients with type i and iu LS compared to 49.4 months for the others, P = .84).

- -

Severe or moderate hypertrophy of the subcutaneous cellular tissue was negatively associated with the diagnosis of LS (odds ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.06–0.54; P < .001).

- -

The cases categorized as type i and iu LS presented a significantly more favorable outcome during the follow-up period than those in other classification categories. Specifically, total or partial improvement was found in 76.0% of cases compared with 25.8% in the other classification categories (odds ratio, 9.1; 95% CI, 2.6–30.8; P < .001).

This study provides a description of the experience accumulated over more than 10 years of follow-up of an outbreak of cases of LS, which affected predominantly female workers in the different municipal offices of Madrid City Council. The actions and preventive measures taken by our institution’s department of occupational health were also made explicit, in line with previous references10.

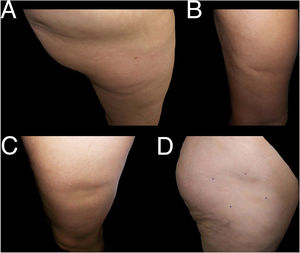

Although the clinical presentation of LS is highly characteristic, when groups of cases appear in a specific work setting, it can be difficult to differentiate the clinical signs and symptoms of genuine LS (Fig. 1) from others (Figs. 2 and 3), in which lesions are assessed that have different locations, forms, or distribution, but share with LS an apparent reduction in the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue.

With the proposed classification, we observed that the cases in group I (those that correspond to the classic description of LS) show a more favorable outcome. This becomes more evident when they are compared with the cases included in the other groups, which tend to remain stable. This more favorable evolution of the cases of LS has been recorded in previous studies: resolution of the lesions in between 6 and 12 months has been reported in most cases and 95% of cases were found to have resolved a year after retirement13.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that, in our series, of the cases in group I, almost half corresponded to unilateral or at least clearly asymmetric forms of presentation. While this asymmetric or unilateral presentation has been reported in other studies, the high frequency in our series contrasts with that of Hermans et al.5, in which 85% of cases presented bilaterally. We believe that if the cause of LS is linked to a local harmful effect (either electrical, electromagnetic, or through repeated pressure), it is unsurprising that it should act with more intensity or exclusively on one of the lower extremities. In fact, it is rare, except in cases that have been attributed to pressure or contact on the anterior surface of the edge of a desk or counter, for the lesions to present such perfect symmetry14. Moreover, in this subgroup of unilateral or asymmetric lesions (iu), the outcome was no different from that found in bilateral and symmetric cases.

We believe that a local predisposition must exist for the lesions to present predominantly on the anterior surface of the thighs. It has been suggested that the location of the lesions may be linked to the muscle insertions in the area15 or to local vascular abnormalities5. Although a previous study found no link between LS and body mass index5, it has also been postulated that, in some women, the female distribution of body fat leads to an increased thickness of the adipose layer in that area of the thighs, which may favor the development of LS7,16. Our findings do not make it possible to confirm this theory, as the most typical cases of LS presented predominantly in women with no marked fat hypertrophy in that region.

Furthermore, even assuming that due to some anatomical circumstance, the anterolateral region of the thighs has a predisposition to present LS lesions, it would be unsurprising to find some cases with other forms or locations17. This circumstance has been observed in some of the cases studied, with lesions in atypical locations but which presented a favorable outcome when the appropriate changes were introduced to the workplace.

In conclusion, the proposed criteria make it possible to differentiate a priori cases of LS (which will probably have a favorable outcome) from others in the form of depressions in the skin surface, which are often persistent.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Bru-Gorraiz FJ, Comunión-Artieda A, Bordel-Nieto I, Martin-Gorgojo A. Lipoatrofia semicircular: estudio y seguimiento clínico de 76 casos en Madrid, España. Propuesta de clasificación. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:15–21.