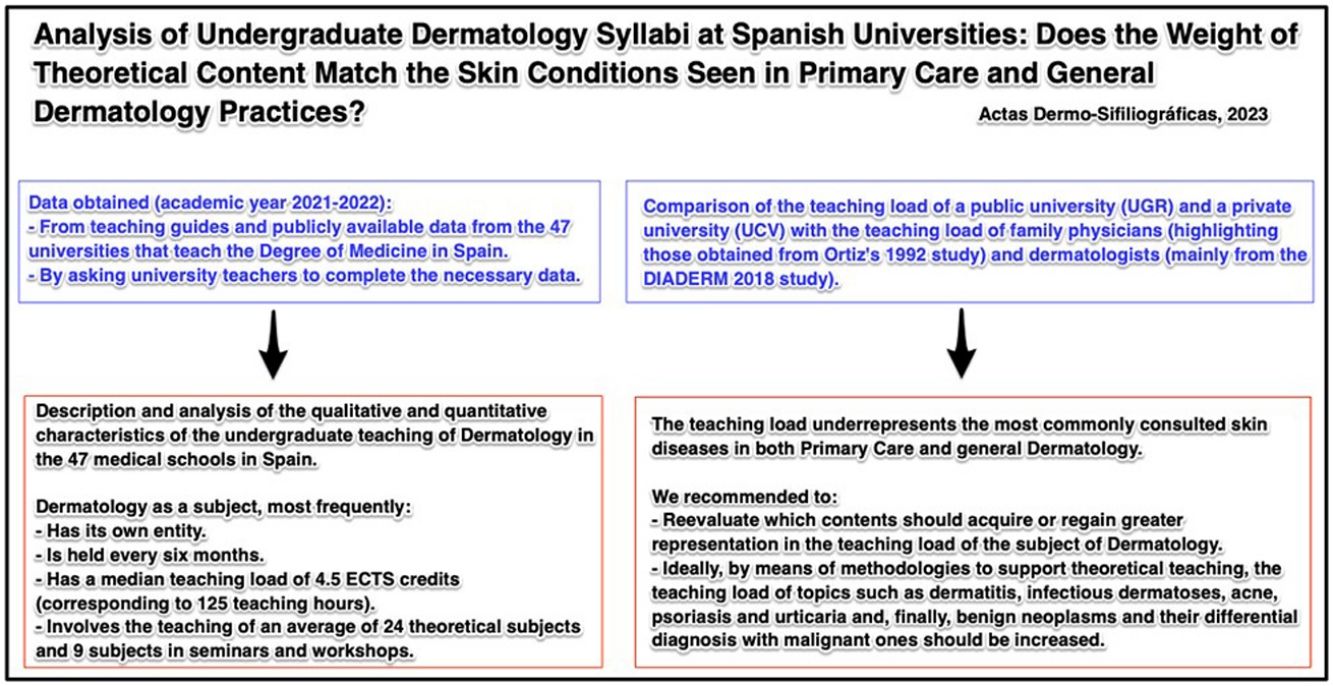

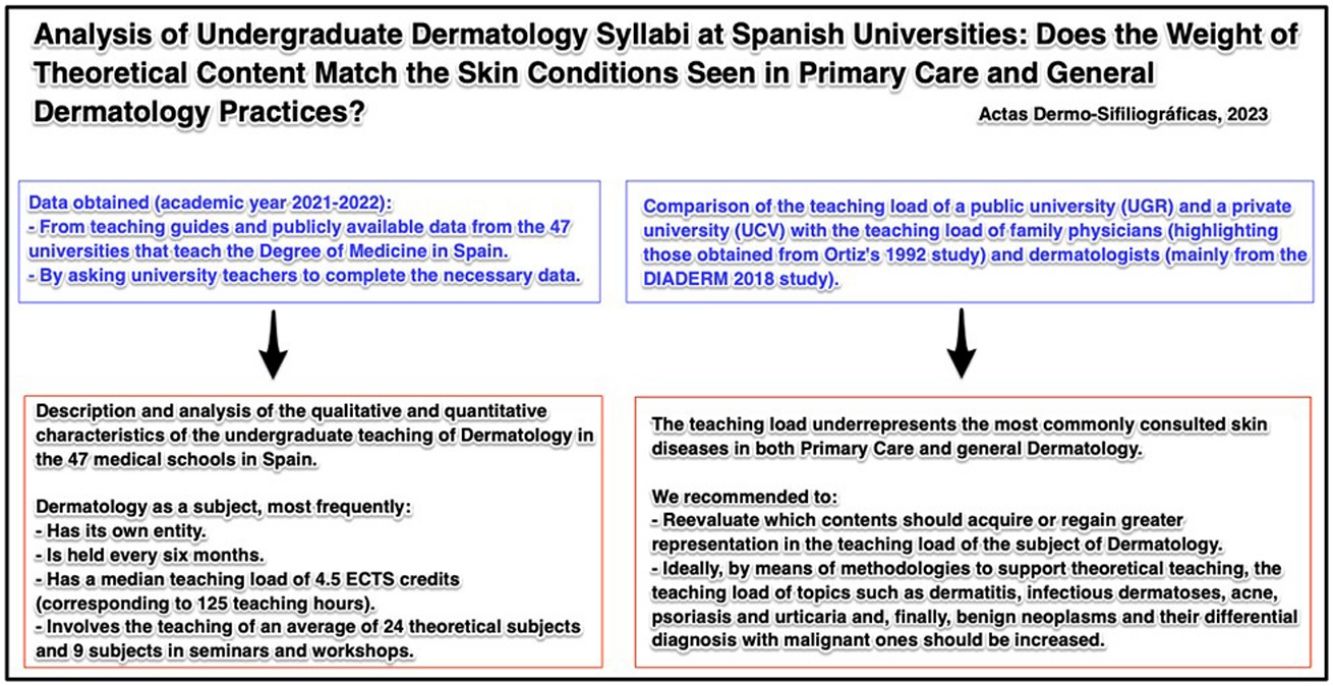

Undergraduate dermatology courses vary in the nearly 50 Spanish medical faculties that teach the subject. This study aimed to describe the characteristics of these courses and to analyze whether the weight assigned to dermatology topics reflects the caseloads of primary care physicians and general dermatologists in the Spanish national health system.

Material and methodsCross-sectional study of syllabi used in Spanish medical faculties during the 2021–2022 academic year. We determined the number of teaching hours in public and private university curricula and compared the weight of dermatology topics covered to the dermatology caseloads of primary care physicians and general dermatologists as reported in published studies.

ResultsMost medical faculties taught dermatology for one semester. The median number of credits offered was 4.5. On average, lectures covered 24 theoretical topics, and seminars and workshops covered 9 topics. We identified a clear disparity between the percentage of time devoted to dermatology topics in course lectures and the skin conditions usually managed in primary care and general dermatology practices.

DiscussionThe skin diseases most commonly treated by primary care physicians and general dermatologists are underrepresented in the curricula of Spanish medical faculties. The topics that should be given more weight in syllabi, or recovered for inclusion in dermatology courses, should be re-examined. Our findings show that the topics that ideally should be emphasized more are types of dermatitis, infectious skin diseases, acne, psoriasis, rashes, and the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant neoplasms. There should be additional support for the theoretical teaching of these topics.

La docencia de pregrado de Dermatología varía entre las casi 50 facultades de Medicina españolas. El presente estudio pretende describir las características de las asignaturas y analizar si la carga lectiva de los temarios se ajusta a la casuística de los médicos de Atención Primaria y dermatólogos generales del sistema de salud español.

Material y métodoEstudio de corte transversal realizado en 2021-2022. Se recabaron datos de universidades a partir de las guías docentes. Se comparó la carga docente de una universidad pública y otra privada con la carga asistencial de médicos de familia y dermatólogos a partir de estudios previos.

ResultadosLa mayor parte de las facultades imparten Dermatología como asignatura semestral, con una mediana de 4,5 créditos, con una media de 24 temas teóricos y 9 temas en seminarios y talleres. Existe una clara divergencia entre la carga docente relativa de los temas teóricos y la carga asistencial por enfermedades cutáneas en Atención Primaria y Dermatología general.

DiscusiónLa carga lectiva infrarrepresenta en gran medida las enfermedades cutáneas más comúnmente consultadas en Atención Primaria y Dermatología general. Resulta oportuno reevaluar qué contenidos deben adquirir o recuperar una mayor representación en la carga docente de la asignatura de Dermatología. Con base en los resultados obtenidos, consideramos óptimo incrementar, idealmente mediante metodologías de apoyo a la docencia teórica, la carga docente referida a cuadros de dermatitis, dermatosis infecciosas, acné, psoriasis, urticaria y, finalmente, las neoplasias benignas y su diagnóstico diferencial con las malignas.

Medical–surgical dermatology and venereology (MSDV) is a specialty that is generating growing interest among medical students, and this interest grows even further once students become more aware of the role of the dermatologist.1 Data from the postgraduate specialization period highlight that, in recent years, the places offered for medical residents in MSDV are systematically chosen by the candidates with the highest grades in the Spanish medical board exam (“examen MIR”). However, most Spanish medical school graduates choose other specialties, with family and community medicine being the most numerous (2338 places of 7989 offered to medical residents [29.3%] went to this specialty).2

The caseload generated by dermatologic conditions in primary care is substantial,3,4 and a high percentage of affected patients are referred from this care level to dermatology.5 Therefore, undergraduate training of future family physicians in diseases affecting the skin, mucosa, and adnexa must be as robust as possible.

The areas covered in the different subjects that make up a degree in medicine are constantly updated to include the latest available scientific evidence. However, the content and workload of the syllabi are generally stable, mainly because the material provided in manuals and texts aims to ensure coherence of content. Teaching materials often underrepresent some diseases, which, for various reasons, receive scant attention in scientific publications and events but are characterized by high incidence, prevalence, and/or disease burden.

Thus, a significant proportion of MSDV specialists and, in particular, family and community medical doctors see patients with very common skin conditions (typical dermatologic conditions in primary care or direct access without triage) on a daily basis. Undergraduate courses either do not cover these conditions or do so in too little detail.

In the present article, our aims were to describe the characteristics of undergraduate dermatology courses in medical schools throughout Spain, to analyze whether the subjects covered and their relative number of teaching hours reflect the caseloads of general dermatologists and family physicians in Spain, and to propose improvements.

Material and MethodsIn order to meet our goals, we designed a cross-sectional study based on data collected during the academic year 2021–2022 on teaching in the specialty of MSDV in Spain. We included data that were publicly available in the syllabus on the web pages of the departments that incorporate the specialty of MSDV in the various schools of medicine. We also included the cut-off grades and cost of registration for first-year undergraduate studies (from the various university websites and from a cut-off grade reference website,6 if the former did not contain all the necessary data). In cases where it was impossible to obtain the syllabus or this was incomplete, we contacted the teaching coordinators responsible for the subject of dermatology.

In order to compare data on relative weight by disease in the syllabus, we selected the public center of the third author (ABE) and the private center of the last author (EN) of the present manuscript as a reference. In both cases, the syllabi were similar to those of the other schools of medicine. Once the theoretical areas of the syllabus were ordered, we attributed a percent weighting of relative and approximate time dedicated to each of the areas addressed, with half of the percentage calculated assigned when it was necessary to account for a very specific disease area. For example, when accounting for the number of teaching hours dedicated to herpes simplex, we assigned half of that of the corresponding subject area, namely, viral infections. We used specific articles as reference studies for the cases seen in daily clinical practice. For specialists in family and community medicine, we used 2 articles (one describing the most frequent diagnoses of skin disease in primary care4 and another analyzing the most frequent referrals from primary care to the specialty of dermatology5); for specialists in MSDV, we used that of DIADERM, sponsored by the Healthy Skin Foundation of the AEDV.7

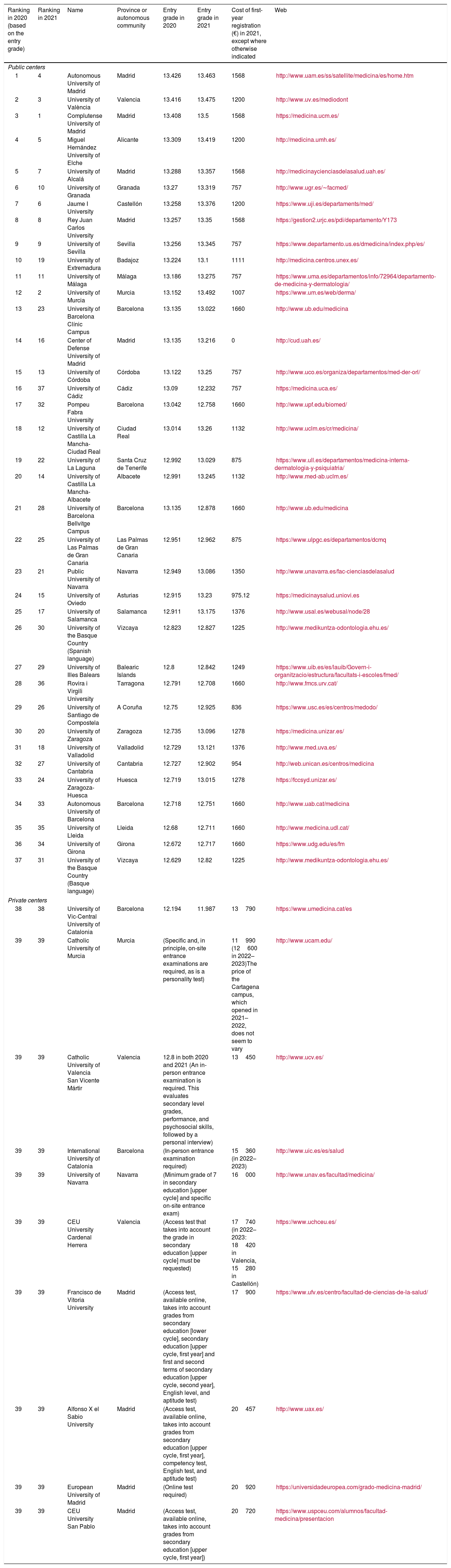

ResultsA medical degree can be studied at 37 public universities and 10 private universities in Spain. The medical schools of some of the public universities require a registration fee and access grades and vary in terms of their characteristics and location (in the same and different provinces). Table 1 shows basic information for the universities.

Spanish Universities With Schools of Medicine: Entry Grade, Location, Cost of Registration, and Webpage.

| Ranking in 2020 (based on the entry grade) | Ranking in 2021 | Name | Province or autonomous community | Entry grade in 2020 | Entry grade in 2021 | Cost of first-year registration (€) in 2021, except where otherwise indicated | Web |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public centers | |||||||

| 1 | 4 | Autonomous University of Madrid | Madrid | 13.426 | 13.463 | 1568 | http://www.uam.es/ss/satellite/medicina/es/home.htm |

| 2 | 3 | University of València | Valencia | 13.416 | 13.475 | 1200 | http://www.uv.es/mediodont |

| 3 | 1 | Complutense University of Madrid | Madrid | 13.408 | 13.5 | 1568 | https://medicina.ucm.es/ |

| 4 | 5 | Miguel Hernández University of Elche | Alicante | 13.309 | 13.419 | 1200 | http://medicina.umh.es/ |

| 5 | 7 | University of Alcalá | Madrid | 13.288 | 13.357 | 1568 | http://medicinaycienciasdelasalud.uah.es/ |

| 6 | 10 | University of Granada | Granada | 13.27 | 13.319 | 757 | http://www.ugr.es/∼facmed/ |

| 7 | 6 | Jaume I University | Castellón | 13.258 | 13.376 | 1200 | https://www.uji.es/departaments/med/ |

| 8 | 8 | Rey Juan Carlos University | Madrid | 13.257 | 13.35 | 1568 | https://gestion2.urjc.es/pdi/departamento/Y173 |

| 9 | 9 | University of Sevilla | Sevilla | 13.256 | 13.345 | 757 | https://www.departamento.us.es/dmedicina/index.php/es/ |

| 10 | 19 | University of Extremadura | Badajoz | 13.224 | 13.1 | 1111 | http://medicina.centros.unex.es/ |

| 11 | 11 | University of Málaga | Málaga | 13.186 | 13.275 | 757 | https://www.uma.es/departamentos/info/72964/departamento-de-medicina-y-dermatologia/ |

| 12 | 2 | University of Murcia | Murcia | 13.152 | 13.492 | 1007 | https://www.um.es/web/derma/ |

| 13 | 23 | University of Barcelona Clínic Campus | Barcelona | 13.135 | 13.022 | 1660 | http://www.ub.edu/medicina |

| 14 | 16 | Center of Defense University of Madrid | Madrid | 13.135 | 13.216 | 0 | http://cud.uah.es/ |

| 15 | 13 | University of Córdoba | Córdoba | 13.122 | 13.25 | 757 | http://www.uco.es/organiza/departamentos/med-der-orl/ |

| 16 | 37 | University of Cádiz | Cádiz | 13.09 | 12.232 | 757 | https://medicina.uca.es/ |

| 17 | 32 | Pompeu Fabra University | Barcelona | 13.042 | 12.758 | 1660 | http://www.upf.edu/biomed/ |

| 18 | 12 | University of Castilla La Mancha-Ciudad Real | Ciudad Real | 13.014 | 13.26 | 1132 | http://www.uclm.es/cr/medicina/ |

| 19 | 22 | University of La Laguna | Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 12.992 | 13.029 | 875 | https://www.ull.es/departamentos/medicina-interna-dermatologia-y-psiquiatria/ |

| 20 | 14 | University of Castilla La Mancha-Albacete | Albacete | 12.991 | 13.245 | 1132 | http://www.med-ab.uclm.es/ |

| 21 | 28 | University of Barcelona Bellvitge Campus | Barcelona | 13.135 | 12.878 | 1660 | http://www.ub.edu/medicina |

| 22 | 25 | University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 12.951 | 12.962 | 875 | https://www.ulpgc.es/departamentos/dcmq |

| 23 | 21 | Public University of Navarra | Navarra | 12.949 | 13.086 | 1350 | http://www.unavarra.es/fac-cienciasdelasalud |

| 24 | 15 | University of Oviedo | Asturias | 12.915 | 13.23 | 975.12 | https://medicinaysalud.uniovi.es |

| 25 | 17 | University of Salamanca | Salamanca | 12.911 | 13.175 | 1376 | http://www.usal.es/webusal/node/28 |

| 26 | 30 | University of the Basque Country (Spanish language) | Vizcaya | 12.823 | 12.827 | 1225 | http://www.medikuntza-odontologia.ehu.es/ |

| 27 | 29 | University of Illes Balears | Balearic Islands | 12.8 | 12.842 | 1249 | https://www.uib.es/es/lauib/Govern-i-organitzacio/estructura/facultats-i-escoles/fmed/ |

| 28 | 36 | Rovira i Virgili University | Tarragona | 12.791 | 12.708 | 1660 | http://www.fmcs.urv.cat/ |

| 29 | 26 | University of Santiago de Compostela | A Coruña | 12.75 | 12.925 | 836 | https://www.usc.es/es/centros/medodo/ |

| 30 | 20 | University of Zaragoza | Zaragoza | 12.735 | 13.096 | 1278 | https://medicina.unizar.es/ |

| 31 | 18 | University of Valladolid | Valladolid | 12.729 | 13.121 | 1376 | http://www.med.uva.es/ |

| 32 | 27 | University of Cantabria | Cantabria | 12.727 | 12.902 | 954 | http://web.unican.es/centros/medicina |

| 33 | 24 | University of Zaragoza-Huesca | Huesca | 12.719 | 13.015 | 1278 | https://fccsyd.unizar.es/ |

| 34 | 33 | Autonomous University of Barcelona | Barcelona | 12.718 | 12.751 | 1660 | http://www.uab.cat/medicina |

| 35 | 35 | University of Lleida | Lleida | 12.68 | 12.711 | 1660 | http://www.medicina.udl.cat/ |

| 36 | 34 | University of Girona | Girona | 12.672 | 12.717 | 1660 | https://www.udg.edu/es/fm |

| 37 | 31 | University of the Basque Country (Basque language) | Vizcaya | 12.629 | 12.82 | 1225 | http://www.medikuntza-odontologia.ehu.es/ |

| Private centers | |||||||

| 38 | 38 | University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia | Barcelona | 12.194 | 11.987 | 13790 | https://www.umedicina.cat/es |

| 39 | 39 | Catholic University of Murcia | Murcia | (Specific and, in principle, on-site entrance examinations are required, as is a personality test) | 11990 (12600 in 2022–2023)The price of the Cartagena campus, which opened in 2021–2022, does not seem to vary | http://www.ucam.edu/ | |

| 39 | 39 | Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir | Valencia | 12.8 in both 2020 and 2021 (An in-person entrance examination is required. This evaluates secondary level grades, performance, and psychosocial skills, followed by a personal interview) | 13450 | http://www.ucv.es/ | |

| 39 | 39 | International University of Catalonia | Barcelona | (In-person entrance examination required) | 15360 (in 2022–2023) | http://www.uic.es/es/salud | |

| 39 | 39 | University of Navarra | Navarra | (Minimum grade of 7 in secondary education [upper cycle] and specific on-site entrance exam) | 16000 | http://www.unav.es/facultad/medicina/ | |

| 39 | 39 | CEU University Cardenal Herrera | Valencia | (Access test that takes into account the grade in secondary education [upper cycle] must be requested) | 17740 (in 2022–2023: 18420 in Valencia, 15280 in Castellón) | https://www.uchceu.es/ | |

| 39 | 39 | Francisco de Vitoria University | Madrid | (Access test, available online, takes into account grades from secondary education [lower cycle], secondary education [upper cycle, first year] and first and second terms of secondary education [upper cycle, second year], English level, and aptitude test) | 17900 | https://www.ufv.es/centro/facultad-de-ciencias-de-la-salud/ | |

| 39 | 39 | Alfonso X el Sabio University | Madrid | (Access test, available online, takes into account grades from secondary education [upper cycle, first year], competency test, English test, and aptitude test) | 20457 | http://www.uax.es/ | |

| 39 | 39 | European University of Madrid | Madrid | (Online test required) | 20920 | https://universidadeuropea.com/grado-medicina-madrid/ | |

| 39 | 39 | CEU University San Pablo | Madrid | (Access test, available online, takes into account grades from secondary education [upper cycle, first year]) | 20720 | https://www.uspceu.com/alumnos/facultad-medicina/presentacion | |

The maximum cut-off grade to enter medical schools in Spain during the academic year 2021–2022 was 13.5. While the lowest published grade (11.99) was for a private center, most private centers did not publish the grade necessary for undergraduate medical studies. Also noteworthy is the variation in the cost of registration for the first year of medicine, both in public centers (depending on the autonomous community, with a minimum of €757 in Andalusia and a maximum of €1660 in Catalonia) and in private centers (ranging from €11990 to 20920).

Table 2 shows the different denominations of the subject in which the course content for MSDV is provided, as well as the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the syllabus. Most medical schools teach the subject during the second cycle of the degree, in year 4 (21 schools) and year 5 (19 schools). The subject mostly covers 6 months and stands alone (i.e., it is not shared with other, similar knowledge areas). The median number of credits (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) is 4.5, that is, 125 official teaching hours (including both active class time and self-study). Students cover a mean of 24 theory areas, with 9 areas covered in seminars and workshops. In general terms, practical classes are the main approach (i.e., a mean of 11hours of seminars and workshops complemented by 20hours of clinical practice sessions), as opposed to the theory classes (mean, 28hours). Finally, in line with the information provided in the syllabus, the number of hours of self-study and tutorials (mean, 55hours) are almost the same as that of theory, seminars/workshops, and clinical practice sessions (mean, 65hours).

Characteristics of Subjects With Specific MSDV Content in Spanish Medical Schools.

| Ranking in 2020 (according to the cut-off grade) | Name of the university | Name of the subject | Year when course is given | By term or year | Total ECTS credits for the subject | ECTS credits for dermatology | No. of theory subjects according to syllabus | Hours of theory according to syllabus | No. of subjects in seminars and workshops | Hours of seminars and workshops | Hours of clinical practice | Total teaching hours according to credits (including self-study) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public centers | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Autonomous University of Madrid | Dermatology | Fifth | Annually | 5 | 5 | 31 | 31 | 7 | 7 | 30 | 125 | |

| 2 | University of València | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 17 | 19 | 5 | 24 | 13 | 112.5 | |

| 3 | Complutense University of Madrid | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 6 | 6 | 30 | 150 | |||||

| 4 | Miguel Hernández University of Elche | Dermatology | Third | First term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 26 | 4 | 112.5 | ||||

| 5 | University of Alcalá | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 11.25 | 33.75 | 112.5 | |

| 6 | University of Granada | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 6 | 6 | 40 | 40 | 10.5 | 10 | 150 | ||

| 7 | Jaume I University | Diseases of the locomotor apparatus, immune system, and skin | Fifth | Second term | 8 | (No data) | 28 | ||||||

| 8 | Rey Juan Carlos University | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 5 | 5 | 30 | 35 | 8 | 10 | 125 | Practice sessions not included in the subject (included in “Clinical Practice II”). The number of hours of clinical practice varies according to the hospital from at least 40h (80h at the coordinating center for the subject). This is usually increased by a further 80-h optional rotation in year 6. | |

| 9 | University of Sevilla | Dermatology | Third | Second term | 6 | 6 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 150 | In addition, optional year 5 course called “Advanced Dermatology: Cosmetic Medicine and Sexually Transmitted Diseases”, with 30h of theory and 30h of seminars |

| 10 | University of Extremadura | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 6 | 6 | 40 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 90 | |

| 11 | University of Málaga | Dermatology, immunopathology, and toxicology | Third | Second term | 9 | 4 | 7 | 20.25 | 12 | 8.25 | 100 | ||

| 12 | University of Murcia | Dermatology | Fifth | Second term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 32 | 40 | 7 | 16 | 112.5 | ||

| 13 | University of Barcelona Clínic Campus | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 5 | 5 | 9 | 25 | 7 | 40 | 125 | ||

| 14 | Center of Defense University of Madrid | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 46 | 125 | |

| 15 | University of Córdoba | MSDV | Fifth | First term | 6 | 6 | 19 | 19 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 150 | |

| 16 | University of Cádiz | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 6 | 6 | 30 | 30 | 5 | 13 | 46 | 150 | |

| 17 | Pompeu Fabra University | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 4 | 4 | 24 | 48 | 8 | 16 | 100 | ||

| 18 | University of Castilla La Mancha-Ciudad Real | Dermatology | Fourth | Annually | 6 | 6 | 24 | 24 | 16 | 26 | 20 | 150 | |

| 19 | University of La Laguna | Dermatology | Fourth | Annually | 4.5 | 4.5 | 21 | 21 | 5 | 5 | 17 | 112.5 | |

| 20 | University of Castilla La Mancha-Albacete | Dermatology | Fourth | Annually | 6 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 12 | 33 | 150 | ||

| 21 | University of Barcelona Bellvitge Campus | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 5 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 36 | 125 | |

| 22 | University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Dermatology, allergology, and clinical immunology | Third | Second term | 7.5 | 4.5 (estimated) | 32 | 32 | 7 | 14 | 14 | 112.5 | |

| 23 | Public University of Navarra | Dermatology | Third | Second term | 3 | 3 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 75 | ||

| 24 | University of Oviedo | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 6 | 6 | 150 | ||||||

| 25 | University of Salamanca | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 4 | 4 | 35 | 39 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 100 | |

| 26 | University of País Vasco (Spanish language) | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 6 | 6 | 28 | 28 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 150 | 5 different groups (in Álava, Guipúzcoa, and Vizcaya, with variations in the syllabus) |

| 27 | University of Illes Balears | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 3 | 3 | 21 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 75 | ||

| 28 | Rovira i Virgili University | Dermatology | Fourth | Annually | 4 | 4 | 26 | 26 | 10 | 100 | |||

| 29 | University of Santiago de Compostela | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 4 | 4 | 30 | 30 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 100 | |

| 30 | University of Zaragoza | Dermatology, immunopathology, and toxicology | Third | Second term | 9 | 4 | 7 | 20.25 | 14.25 | 6 | 100 | ||

| 31 | University of Valladolid | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 5 | 5 | 25 | 25 | 8 | 12 | 125 | ||

| 32 | University of Cantabria | MSDV | Fourth | First term | 6 | 6 | 30 | 30 | 10 | 14 | 150 | ||

| 33 | University of Zaragoza-Huesca | Dermatology | Third | Second term | 9 | 4 | 7 | 20.25 | 14.25 | 6 | 100 | ||

| 34 | Autonomous University of Barcelona | Clinical dermatology | Fifth | Annually | 4 | 4 | 25 | 8 | 10 | 100 | |||

| 35 | University of Lleida | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 4 | 4 | 26 | 25 | 16 | 16 | 100 | ||

| 36 | University of Girona | Dermatology: (1) Sensory organs: the skin and (2) Plastic surgery | Fifth | Second term | 11 | 6 (estimated) | 19 | 18 | 8 | 150 | |||

| 37 | University of País Vasco (Basque language) | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 6 | 6 | 28 | 28 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 150 | 5 different groups (in Álava, Guipúzcoa, and Vizcaya, with variations in the teaching guidelines) |

| Private centers | |||||||||||||

| 38 | University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia | Sensory organs: the skin | Fifth | Annually | 5 | 5 | 17 | ||||||

| 39 | Catholic University of Murcia | Dermatology | Fourth | First term | 4.5 | 4.5 | 43 | 26 | 6 | 13.5 | 125 | ||

| 39 | Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 6 | 6 | 25 | 45 | 5 | 17.5 | 112.5 | ||

| 39 | International University of Catalonia | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 4 | 4 | 30 | 30 | 14 | 16 | 100 | Also offers an optional course in Practical Dermatology | |

| 39 | University of Navarra | Dermatology | Fifth | First term | 3 | 3 | 27 | 27 | 7.5 | 75 | |||

| 39 | CEU Cardenal Herrera University | Diseases of the organs, skin, and senses | Fourth | Second term | 9 | 3.5 (estimated) | 27 | 0 | 100 | According to the syllabus, in-class activity is limited to 100h of theory (same as before COVID-19 pandemic) | |||

| 39 | Francisco de Vitoria University | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 3 | 3 | 14 | 25.5 | 35 | 75 | |||

| 39 | Alfonso X el Sabio University | Dermatology | Fourth | Second term | 6 | 6 | 28 | 28 | 7 | 7 | 30 | 150 | |

| 39 | European University of Madrid | Clinical training viii: Dermatology | Fifth | Annually | 8 | 8 | 30 | 50 | 8 | 100 | 200 | ||

Abbreviations: ECTS, European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System; MSDV, medical–surgical dermatology and venereology.

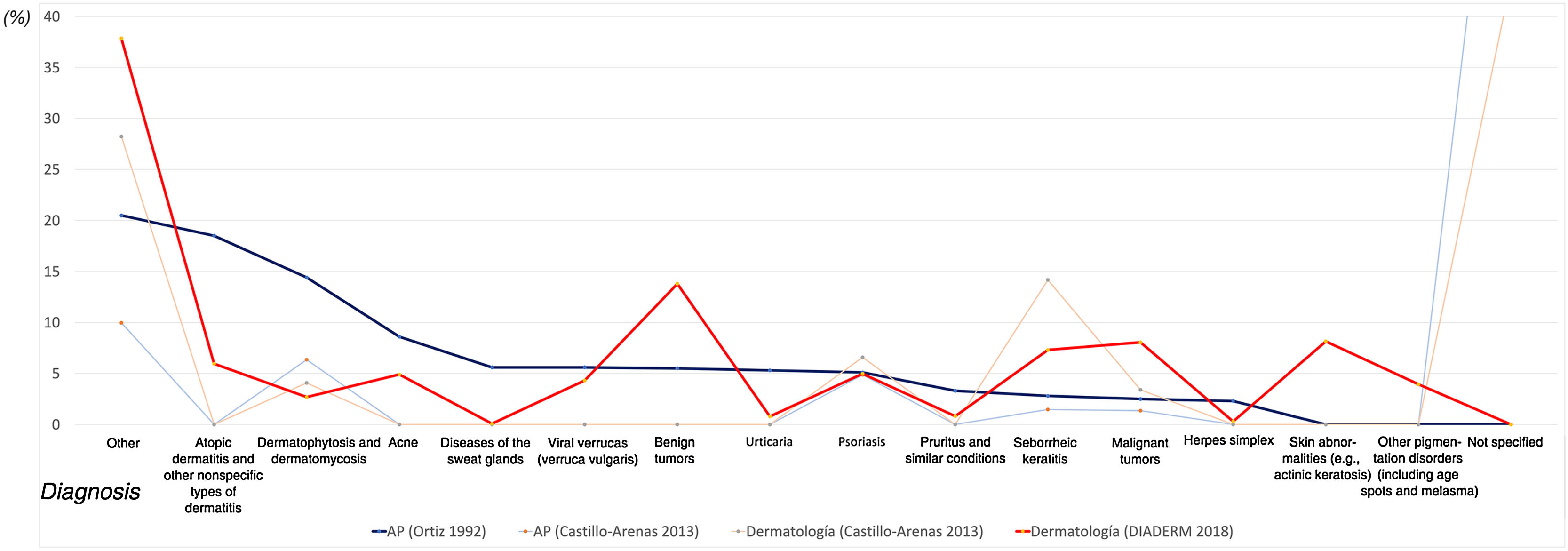

Fig. 1 shows the caseload (as a percentage of the total number of diagnoses) for diseases reported in primary care and the dermatology department from various series.4,5,7 It also shows, in part, the structure of the Spanish health system, where acute conditions, such as herpes and mycosis, are more commonly seen in primary care (or by general dermatologists who see patients without triage); other lesions are managed mainly in specialized care. Acne, dermatophytosis, and dermatitis were the most frequently diagnosed skin diseases in primary care (corresponding to 41.5% of diagnoses based on reported data4), whereas benign and malignant neoplasms and skin abnormalities (including actinic keratosis) are more common in dermatology (37.3% of diagnoses in DIADERM7).

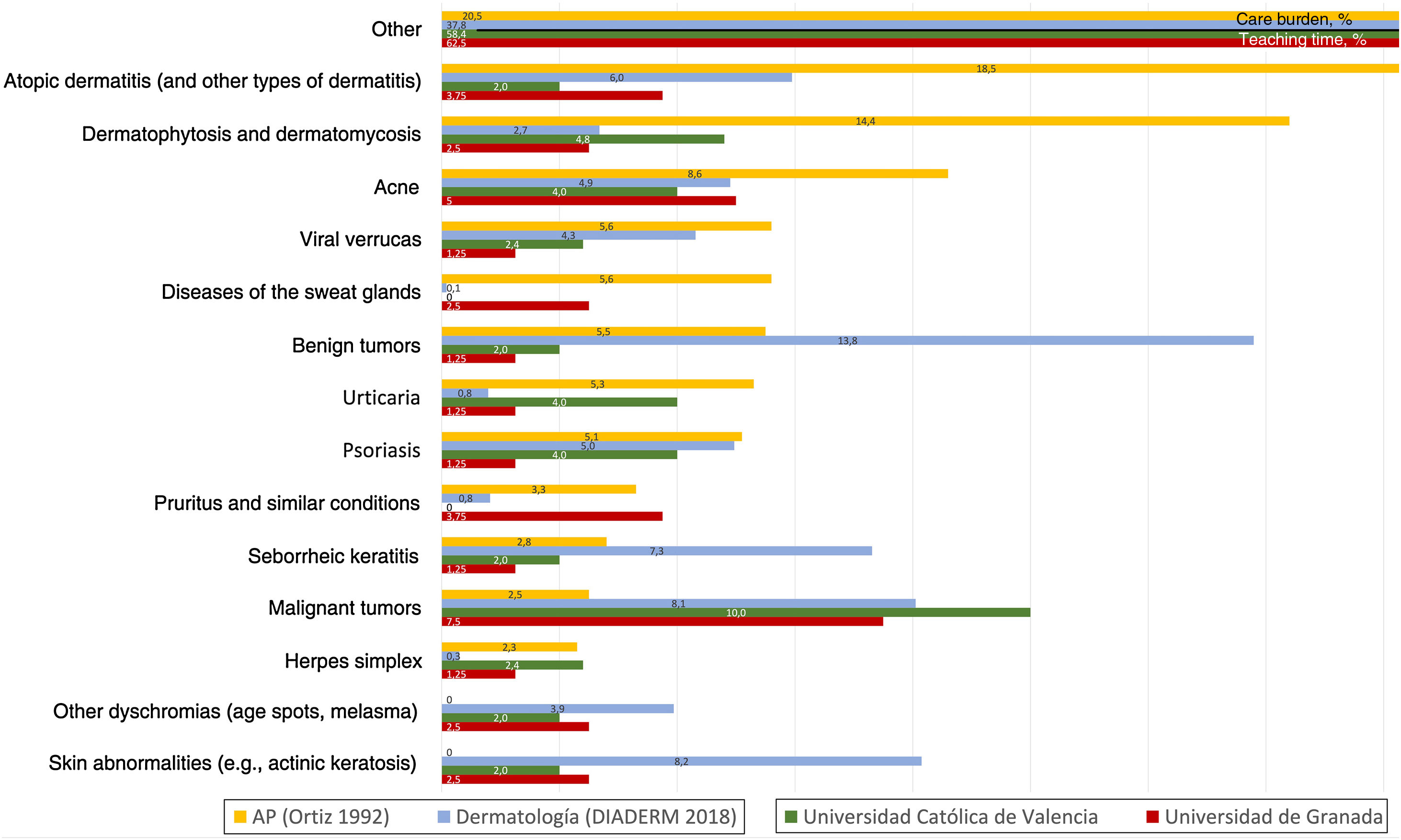

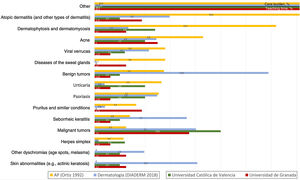

Fig. 2 shows the difference between the frequency of diseases (caseload) and the relative teaching time for the theory areas. Only in the case of acne and malignant neoplasms in the 2 universities studied did teaching time reflect the caseload in the clinical practice of general dermatologists in Spain, in contrast with family physicians.

Relative percentage of care burden by skin disease according to studies from primary care and dermatology compared with the relative percentage of teaching time according to the theory syllabus by skin diseases. Data from the schools of medicine of the Universtity of Granada and the Catholic University of Valencia.

In the present study, we address the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of undergraduate subjects aimed at MSDV in Spain. Our comparison of the theory syllabus and the relative teaching workload for specific diagnoses with data from previous studies on the caseload of dermatologists and primary care physicians showed that the teaching workload only approaches that of general dermatologists for 2 diagnoses.

Therefore, according to the data presented, diagnoses of dermatological diseases by Spanish dermatologists and primary care physicians are underrepresented in the theory taught in subjects aimed at MSDV in Spain.

We found no other scientific studies applying a similar approach. We selected diagnoses and grouped their frequency in the 3 Spanish reference articles based on similar approaches and attempted to obtain comparable diagnostic groups.

Our study has a series of strengths, for example, its relevance, its approach (which we consider novel), and the recording of comparative data from universities with medical schools in Spain.

We are aware that the importance of a disease depends not only on its frequency, but also on its relevance (associated morbidity and mortality), and that, consequently, our methodology may be subject to limitations. However, we must ask ourselves what a degree subject aims to achieve. Does it intend to represent the areas a specialist should concentrate on or does it intend to train the postgraduate physician (in general and in family and community medicine) in the identification and basic management of the diseases most commonly seen in the clinic? If we take the latter intention, then we think that taking morbidity and mortality into account is not indispensable in terms of the methodological approach used. While the syllabi of the 2 medical schools selected are very similar to those of the other schools, the subjects and their estimated time requirements do not fully reflect the reality of teaching practice, in which the day-to-day work could be used to apply corrective factors in seminars, workshops, tutorials, self-study, and, of course, practical clinical training. We believe that, regarding these adaptations to the curriculum of the undergraduate subject, it is essential not to exclude the students’ opinion on and vision of how to address them.

One of the limitations in the approach to the case burden generated by skin diseases in primary care is the limited number of studies that enable us to assess it in this setting. Therefore, we think that studies such as those of DIADERM8 should be repeated periodically. The data collected in DIADERM in 20167 and the methodology applied could be used in studies in other medical specialties, such as family and community medicine. With respect to the public health system, studies such as DIADERM have highlighted a series of key areas: avoidable referrals from primary care to dermatology,9 whether there are seasonal variations in diagnoses,10 how telemedicine has been applied,11 and the difficulties experienced in coding dermatologic diagnoses.12 These studies could be reproduced in a similar fashion for other specialties. They have also revealed the scale of major areas in MSDV, such as cutaneous oncology,13 and some less well represented areas in most settings, such as anogenital and venereal diseases.14

ConclusionsTeaching time devoted to theory largely underrepresents the skin diseases most commonly seen in primary care. We believe that medical graduates should be trained in the identification and basic management of the most frequent diseases seen in general medicine and in primary care. Given that general, rural, and family and community physicians receive between 2.5% and 20% of visits associated with skin diseases, it seems appropriate to reevaluate the type of content that should be assigned more weight or recover teaching hours in the subject of dermatology.

Therefore, based on the results obtained, we believe that it is essential to increase, ideally by means of approaches that support the teaching of theory (e.g., seminars, workshops, case studies, tutorials, guided self-study), the number of hours allocated to dermatitis, infectious skin diseases, acne, psoriasis, urticaria, and, finally, benign neoplasms and the differential diagnosis with malignant neoplasms.

Reconsidering teaching hours by subject or adjusting content that is an alternative to theory classes would result in improved teaching that is better adjusted to the real-world situations students face after graduation and that enables a more suitable approach to and care for the patients they will treat.

FundingThis study was presented during the Fifth Call for Innovative Teaching Projects of the Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir and was awarded a grant, which went toward its completion.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.