Histoplasmosis is a systemic infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. In immunocompromised patients, primary pulmonary infection can spread to the skin and meninges. Clinical manifestations appear in patients with a CD4+ lymphocyte count of less than 150 cells/μL.

Coccidioidomycosis is a systemic mycosis caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. It can present as diffuse pulmonary disease or as a disseminated form primarily affecting the central nervous system, the bones, and the skin.

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans (var. neoformans and var. grubii) and Cryptococcus gattii, which are members of the Cryptococcus species complex and have 5 serotypes: A, B, C, D, and AD. It is a common opportunistic infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS, even those receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Histopathologic examination and culture of samples from any suspicious lesions are essential for the correct diagnosis of systemic fungal infections in patients with HIV/AIDS.

La histoplasmosis es una micosis sistémica causada por el hongo dimorfo Histoplasma capsulatum. En pacientes inmunocomprometidos se produce una progresión de la enfermedad pulmonar y la diseminación en la piel y las meninges. Las manifestaciones clínicas aparecen cuando los niveles de linfocitos CD4 son menores a 150 células/μl.

La coccidioidomicosis es una micosis sistémica causada por Coccidioides immitis y Coccidioides posadasii. Se presenta como una forma pulmonar difusa o diseminada, con manifestaciones en el sistema nervioso central, los huesos y la piel, fundamentalmente.

La criptococosis está causada por diferentes especies de Cryptococcus species complex, Cryptococcus neoformans (var. neoformans y var. grubii) y Cryptococcus gattii, que conforman los 5 serotipos identificados: A, B, C, D y AD. Es una infección oportunista común en pacientes con VIH/sida, incluso si están en tratamiento con antirretrovirales.

El estudio histopatológico y el cultivo de cualquier lesión sospechosa son fundamentales para un correcto diagnóstico de estas micosis sistémicas en pacientes infectados por el VIH/sida.

Systemic mycoses can be classified according to whether the causative agent is a systemic fungal pathogen (Blastomyces dermatitidis, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum [variants capsulati and duboisii], and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis) or one of an increasing number of opportunistic fungal pathogens normally found in the environment. These fungi are thermally dimorphic microorganisms with 2 phases. Transition from the mycelial to yeast phase is normally associated with a change in temperature from 25°C to 37°C. With the exception of C immitis, which forms spherules with endospores, the natural phase of each of these fungi is a mold, while the histic form is a yeast.1–4

All these fungi are essentially pulmonary pathogens and inhalation of conidia is the most likely route of entry to the respiratory tract. Skin manifestations generally require disseminated infection but can occasionally be due to traumatic implantation of material contaminated with the fungi. The majority of deep-seated mycoses usually occur in certain regions of North America, South America, Central America, and Africa. These infections and their corresponding skin manifestations have become the most frequent opportunistic infection among the increasingly large populations of individuals with severe immune deficiencies, including AIDS. Skin manifestations are important for 2 reasons. First, they may preempt other clinical manifestations, including pulmonary or neurologic conditions, and so their detection can enable early treatment. Second, a skin biopsy can be readily taken with minimally invasive procedures. The biopsy samples enable microbiological culture and histopathologic study, which are sometimes necessary for correct diagnosis. The diagnostic yield for such procedures is high. The present article should therefore be useful for younger dermatologists and for all those interested in the study of mycosis. We have focused on 3 types of infection—histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis—as these are the most prevalent. They are also the infections for which we have most information and experience.

We have conducted a thorough review of the literature on epidemiologic, clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic information pertaining to endemic systemic mycoses (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis) in adult patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS, from the first reports of cases until the end of 2011. We have also included data and images from our own experience.

HistoplasmosisEtiologyHistoplasmosis is caused by the dimorphic fungus H capsulatum, which has 2 variants that are pathogenic for humans, the duboisii variant, found mainly in Africa, and the capsulatum variant, found mainly in North and South America. The disease can, however, occur throughout the world.5 The fungus is present in the excrement of bats and certain birds, and can remain in the environment for prolonged periods.

Transmission MechanismInfection is acquired by inhalation of the mycelial form and primarily affects the lungs. Spontaneous resolution occurs in 95% of the patients, and infection induces immunologic memory.6 The pathogenic process after inhalation of conidia initially involves localized pneumonitis, followed by hematogenous spread after 2 weeks, and cell-mediated immune response after 3 weeks. In patients with AIDS, infection can progress or become reactivated when CD4 levels decrease.7

EpidemiologyHistoplasmosis has been accepted as one of the defining diseases of AIDS since 1987. However, with the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), CD4+ levels have come under better control with a decline in the incidence of fungal infections 20% to 25% below the incidences in the 1990s.8–11

Overview of SymptomsThe symptoms of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis include fever, general malaise, weight loss, cough, and chest pain. Infection can follow a rapid course with involvement of the reticuloendothelial system, in which case it is almost always fatal. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement can be primary or it may be associated with disseminated disease (5% to 10% of cases). Manifestations include meningitis, encephalitis, and vascular syndromes.7,12 Half the patients with disseminated forms have impaired adrenal function, but only 7% actually present with adrenal insufficiency. Ocular damage in the form of panophthalmitis and uveitis may occur. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome has been reported after uveitis or choroiditis; in most cases (90%), these processes are unilateral.13

Skin ManifestationsPrimary skin lesions are uncommon. Skin involvement occurs in association with disseminated histoplasmosis in 70% to 80% of cases (Figs. 1–3). Skin manifestations are observed mainly in adults and more frequently in South America, where the strains are thought to be more virulent. There are no specific skin lesions. Two-thirds of patients experience mucosal involvement, particularly in the oropharyngeal region (Fig. 4). Erythema nodosum or polymorphous erythema may also be present in association with pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Laboratory observations used to support diagnosis of histoplasmosis include anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, abnormal liver enzymes, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin.

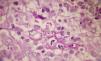

A smear with May-Grünwald-Giemsa or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains can be obtained from lesions, bone marrow samples, sputum samples, or material obtained from bronchoscopy to visualize the yeasts (Fig. 5).14 Intradermal reaction is not very useful in patients with AIDS. Although histopathologic study with PAS, Giemsa, or Gomori-Grocott stains is very helpful, culture is still the gold standard for diagnosis.

Currently, laboratory techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunodiffusion, and complement fixation can be used to identify reactive antibodies. These tests are positive in 90% of the patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis without immunosuppression, although they are often negative in patients with AIDS.15

Finally, we should remember that measurement of a polysaccharide antigen in serum and urine is the most sensitive and rapid test, although it may yield false positives in patients with other mycotic diseases, particularly blastomycosis.15,16

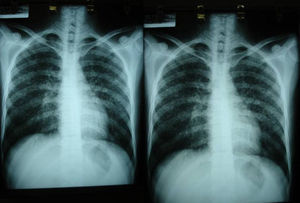

Imaging tests may not be positive in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis. Thus, H capsulatum has been isolated from the lungs of patients with AIDS, and so a negative result does not rule out the disease. Imaging is used essentially to determine the extent of disease (Fig. 6).

Differential DiagnosisDifferential diagnosis includes conditions such as secondary syphilis and molluscum contagiosum (Table 1).16,17

Treatment and Prophylaxis for Endemic Fungal Infections.

| Infection | Skin/Mucosal Manifestations | Differential Diagnosis | Treatment | Secondary Prophylaxis | Primary Prophylaxis |

| Histoplasmosis | Skin: papules, pustules, nodules, ulcers, molluscoid lesionsMucosae: oropharynx (vegetative lesions, nodules, ulcers) | Secondary syphilis, prurigo, cryptococcosis, candidiasis, molluscum contagiosum, penicilliosis | Disseminated disease: Amphotericin B (3 mg/kg/d) for 2 weeks followed by itraconazole (200 mg/twice daily) for 10 weeksIsolated skin lesions: itraconazole 300mg twice daily for 3 days followed by 200 mg/twice daily for 12 weeks | Itraconazole (200mg twice daily or 400mg once daily) or amphotericin B (50 mg/week); drug indicated for intermittent therapy after 12 months in patients with immune reconstitution with HAART. | Itraconazole (200 mg/d) in patients living in endemic areas with CD4<150 cells/μL |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Papules, verrucous and/or granulomatous lesions, abscesses, and pustules | TB, sporotrichosis, molluscum contagiosum, HSV, rhinophyma, Kaposi sarcoma, and bacterial cellulitis | Disseminated disease: amphotericin B (0.5–0.7 mg/k/d), for an indeterminate duration | Fluconazole (400 mg/d) or itraconazole (200mg twice daily), for an indeterminate duration | Not recommended |

| Cryptococcosis | Papules, pustules, vesicles and/or ulcers, verrucous or necrotic herpetiform, acneiform and varioliform plaques, or even plaques similar to those in Kaposi sarcoma and molluscum contagiosum | Molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex, rhinophyma, Kaposi sarcoma, and bacterial cellulitis | Disseminated disease: Amphotericin B (0.7–1 mg/kg for 7 days) + flucytosine (100 mg/kg for 7 days) for 2 weeks followed by fluconazole (400 mg/d) for 10 weeksIsolated skin lesions: Fluconazole (200–400 mg/d) or itraconazole (400 mg/d) for 2 weeks | Fluconazole (200–400 mg/d) or itraconazole (400 mg/d), intermittent once immune reconstitution reaches CD4 >10–150 cells/μL for ≥6 months | Debatable |

Abbreviations: HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HSV, herpes simplex virus; TB, tuberculosis.

The international guidelines for treatment of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS have changed since the introduction of ART. In fact, such therapy is considered fundamental for the prevention and control of opportunistic mycoses in these patients (Table 1).9

CoccidioidomycosisEtiologyCoccidioides species are an imperfect dimorphic fungus. As a parasite, this organism takes the form of a spherule with endospores, whereas the saprophytic form is a mold with a septate mycelium that produces thallic conidia. The mycelium alternates between disjunctor, degenerate, and empty cells. Coccidioidomycosis is a systemic mycosis caused by microorganisms of the Coccidioides genus, which includes 2 species, C immitis and Coccidioides posadasii.5

Transmission MechanismInfection is acquired through inhalation of arthrospores from soil or laboratory cultures. Once inhaled, the spores become lodged in the pulmonary alveoli and activate the host's first line of defense, comprising polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages. The complement system is also activated. The macrophages engulf the conidia but lysis does not occur until activation by type 1 T helper cells. Eosinophils and mastocytes are also activated, releasing large amounts of immunoglobulin E. The fungus, in addition to having a high biotic potential (each spherule can produce up to 800 endospores), has defense mechanisms to protect it from the host’ immune response. These defense mechanisms include production of metalloproteinase 1, which degrades a protein on the surface of the endospores (spherule outer wall glycoprotein). As this glycoprotein interacts with the antibodies to trigger opsonization of the parasite, its production enables the pathogen to elude recognition by the immune system and persist in the host. C posadasii produces ammonia, which favors infection by increasing the pH in infected tissues. In vivo experiments have shown that the microorganism can synthesize melanin.5

Infection is not transmitted from one person to another because it cannot be acquired from spores present in expectoration or exudate although perinatal transmission is possible. Infection of the genitourinary tract of the mother can cause infection of the placenta and coccidioidal endometriosis with aspiration of infected amniotic liquid and consequent intrauterine or perinatal transmission.18–22

EpidemiologyCoccidioidomycosis is the most common and most serious respiratory mycosis. Per year, there are thought to be between 45 000 and 100 000 cases, 50% of which originate in the south of the United States.5,23 In the last 2 decades, several endemic areas have been identified: northwest Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, and Argentina.24

Overview of SymptomsThe first reports of AIDS-related coccidioidomycosis appeared a few years after the first reports of the syndrome itself. The course is progressive and can lead to severe respiratory failure.25–27

Coccidioidomycosis has been detected in almost all organs: the eyes, larynx, thyroid glands, peritoneum, prostate, kidneys, and uterus, as well as in prostheses and peritoneal shunts. Bone involvement is uncommon. Vertebral discs are rarely affected, but paraspinal masses with fistulas are common. Other bones that may be affected include the cranium, ribs, tibia, femur, metacarpals, and metatarsals.

Dissemination to the CNS is the most serious form of infection. Such spread usually manifests as chronic granulomatous meningitis, with involvement of the basilar meninges; hydrocephaly may be present.28,29

Skin ManifestationsThe skin is the structure most commonly involved when disease is disseminated. Manifestations are varied and lesions may coalesce to form plaques (Figs. 7 and 8). The granulomatous lesions show minimal inflammation. With ulcerated lesions, the possibility of a fistula should be considered.30

Diagnosis is based on intradermal reactions to coccidioidin or spherulin, which is the most sensitive agent. The test is positive from between 2 days to 3 weeks after infection and remains positive for several years.5 Imaging is negative in up to 98% of patients with AIDS in the first 48 to 72hours.26

Serology tests are less reliable in HIV-infected patients, although they are positive in 68% to 74% of cases. However, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and complement fixing show high sensitivity. Tube precipitation tests are very specific. Binding of particles to latex is positive in 70% of cases.

Techniques such as fluorescent antibodies, monoclonal antibodies, PCR, and in situ hybridization can also be used for detection.

Cultures can be obtained in secure laboratories equipped to handle hazardous materials. Microscopic analysis reveals slender, septate hyphae with rectangular arthrospores.5

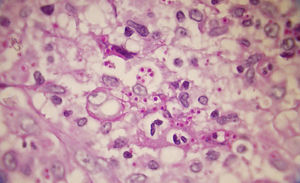

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy samples from skin lesions and lesions in other tissues (Fig. 9) often reveals spherules measuring 10 to 80μm, with a doubly refractile wall and endospores measuring 2 to 5μm. However, these structures can be visualized better with PAS and Gomori-Grocott stains (Fig. 10). Histopathology also reveals a granulomatous reaction around the spherules.5

The fungus can be isolated in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in only half the cases: diagnosis is confirmed with a positive finding for immunoglobulin G antibodies.26 Radiographic studies are not specific for coccidioidomycosis.5

Differential DiagnosisThe differential diagnosis should initially include tuberculosis in its different clinical manifestations and then consider sporotrichosis, among other conditions (Table 1).31

TreatmentTreatment for the different forms of coccidioidomycosis is subject to debate. Given the widely variable results and limited number of controlled studies, it is hard to propose universal recommendations for the treatment of each clinical manifestation in HIV-infected patients, particularly regarding the duration of therapy (Table 1). In a patient with disseminated coccidioidomycosis, successful use of interferon gamma at a dose of 50μg/m2, 3 times a week, has been reported.29 Patients with initially negative serology may experience a delay in improvement and the findings do not necessarily correlate with disease course. The duration of therapy has not been defined, although treatment for at least 1 year is recommended.32,33

CryptococcosisEtiologyThe Cryptococcus genus includes many species. Of these, human infection only occurs with Cryptococcus neoformans (variant neoformans and variant grubii) and Cryptococcus gattii, of which 5 serotypes—A, B, C, D, and AD—have been identified.1 These microorganisms have a firm wall and a spherical or elliptical shape. Characteristically, they have a thick capsule that can be stained with freshly prepared India ink. The capsule is composed of polysaccharides, mainly glucuronoxylomannan (90%–95%), galactoxylomannan (5%–8%), and mannoproteins (<1%).34

Transmission MechanismC neoformans is ubiquitous in the urban environment and is found in pigeon excrement and, to a lesser extent, bat excrement, whereas C gattii has been associated with certain trees and is limited to tropical and subtropical regions.34–38 Penetration occurs mainly via the respiratory tract and, more rarely, via the gastrointestinal tract and the skin.2 Once inside the host, the yeast can change the composition and size of the capsule to increase its chances of resisting or eluding the host's defense mechanisms. These changes determine the principal virulence factor of the microorganism, which confers an ability to avoid phagocytosis, change its phenotype, and, in some cases, produce melanin.39

EpidemiologyCryptococcosis is a common opportunistic infection in patients with HIV infection/AIDS; in fact, it is the most frequent disseminated fungal infection in these cases. Immune cell dysfunction is considered the main risk factor so patients with HIV infection/AIDS are highly susceptible despite treatment with ART.40

C neoformans variant neoformans (serotype D) and especially the variant grubii (serotype A) is the species implicated in the infection of immunocompromised patients, including those with HIV infection or cancer and solid-organ transplant recipients.5C gattii has recently been described as an emerging species in the northwest region of North America, although mainly immunocompetent patients are infected.

In Europe, C neoformans is the cause of 20% of infections in patients with HIV infection/AIDS. In Africa, it is the initial infection in 20% to 30% of patients and responsible for 20% to 40% of deaths attributable to AIDS. Extrapulmonary cryptococcosis is even considered a defining infection of AIDS; this form is detected in 4.3% of cases and presents more frequently in the skin, prostate, and eyes. Cryptococcal meningitis is more common in patients with CD4+cell counts below100 cells/μL.41

Overview of SymptomsCryptococcosis causes pneumonia in most cases, but pulmonary cryptococcomas have also been reported and, in 10% of patients, hematogenous spread may occur to other organs, mainly the CNS. Often, on diagnosis, infection is disseminated and meningitis is present in up to 60% to 70% of patients. The onset of meningitis is insidious, with impaired hearing and higher-level mental processes, headache, fatigue, dizziness, irritability, and/or impaired coordination. Other organs that may be infected include the kidney, liver, and genitourinary tract. The skeletal system may also become involved.42

Skin ManifestationsSkin lesions, which are present in 10% to 15% of patients, may be single or multiple and appear predominantly on the trunk and face (Figs. 11 and 12). The clinical presentation is extremely varied. Skin lesions may arise from disseminated C immitis infection, from old quiescent pulmonary lesions that are reactivated when the effectiveness of specific immune mechanisms are undermined, or from propagation of the pathogen from underlying lymph node, skeletal, or articular lesions. Usually, multiple lesions develop, with the first ones appearing on the head and neck (near natural orifices). Subsequently, they coalesce to form plaques and become verrucous. Cutaneous granulomas appear in the vicinity of fistulous tracts, which tend to heal while the lesion progresses at the borders. In other cases, chronic bone lesions induce secondary involvement of soft tissue. The most characteristic lesions are described in Table 1.43,44

The cryptococcus can usually be identified by laboratory analysis of blood, bone marrow, CSF, and samples from the eye, respiratory tract, skin and mucosae, urine, and other tissues. From any patient who is positive for the cryptococcal antigen, in whom encapsulated yeasts are detected in direct examination or histology, or in whom C neoformans is isolated from any other body site, it is recommended to obtain, immediately inspect, and culture samples from the CSF, blood, urine, and serum. This process will enable the assessment of the severity of infection and the optimal induction of treatment.5,45

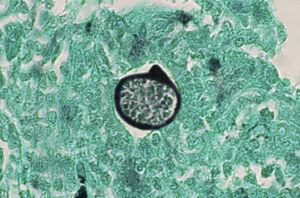

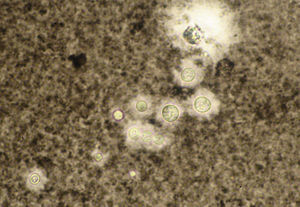

The India ink test can be performed with any body fluid. Yeasts measuring 2 to 5μm are observed to be surrounded by a mucoid capsule that remains unstained (Fig. 13). This test is quick (taking less than a minute) and very specific though sensitivity is low as only 50% of cases are positive.46

Tissue sections can be stained to facilitate visualization of the fungus. The most useful stains are PAS, Grocott, Papanicolaou, and Gram. For diagnosis of clinical samples, the fungus can be also be inspected by fluorescence microscopy with calcofluor-white staining or phase contrast microscopy.5

Any tissue or body fluid can be cultured. The fungi grow in temperatures ranging from 25°C to 37°C and the yeast colonies can be white, yellow, or light-coffee colored. A cryptococcal species is definitively identified be means of the carbohydrate utilization test and production of pigment on Niger agar (Gyzotia abissinica).47

Differential DiagnosisDifferential diagnosis should include molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex virus, rhinophyma, Kaposi sarcoma, and bacterial cellulitis (Table 1).40–42

Treatment and Follow-upThe treatment of choice for disseminated infection is a combination of intravenous amphotericin B and flucytosine. This combination allows the dose of both drugs to be reduced, thereby lowering toxicity and side effects. It is important to remember that flucytosine increases hematologic toxicity in patients receiving treatment with zidovudine, so renal function and flucytosine levels should be closely monitored (Table 1). Two predictive factors for mortality have been proposed: a CD4+ count less than 50 cells/μL and a history of oral candidiasis prior to starting ART.42,43

Skin Manifestations and Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory SyndromeWith the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of many opportunistic infections has decreased in HIV-infected patients. At the same time though, these agents have brought new problems, such as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), an adverse effect of HAART-induced reconstitution of the antigen-specific immune response that is manifest as the clinical onset of preexisting subclinical infections or the vigorous onset of autoimmune and neoplastic diseases.48–50

Cases of skin manifestations of histoplasmosis have been reported. In most cases, the patients presented with generalized papular or crusty lesions (Fig. 14) and, in 1 case in particular the patient had a nodular lesion on the face, with accompanying fever and lymphadenitis. Histology of samples from skin and lymph nodes showed giant cell granulomas with necrosis and yeast cells. H capsulatum was cultured from blood samples and this microorganism was also isolated from skin and the lungs. The treatment is the same antifungal therapy as described above.51

The exact incidence of C neoformans-related IRIS is not known even though this microorganism is always detected in series and case reports of patients with IRIS. In most cases, the cause is reactivation of previously treated infections, suggesting that the condition is an immune response to inadequately treated disease or an inflammatory reaction to certain residual antigens. IRIS presents mostly in the form of meningitis, although cases presenting as lymphadenitis and mediastinitis have also been reported.

Skin manifestations are uncommon, but when present they appear as large single or multiple masses or large ulcers. In some cases, surgery is required to excise the nodular lesions while HAART continues.52

There have been no reports of IRIS in patients with HIV/AIDS and coccidioidomycosis.

Practical Consequences in SpainDermatologists should be prepared to detect rare diseases and atypical presentations of the most common infections—skin infections in particular—in patients with a compromised immune system, including those with HIV infection/AIDS. The impairment and dysregulation of immunity caused by HIV makes patients are susceptible to a wide range of skin infections. Lesions may show less inflammation than is usual or be more generalized, disfiguring, and destructive. Lesions can also be atypical when HIV-infected patients develop lesions caused by simultaneous infection of more than a single pathogen.53

Histoplasmosis is a common opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients who live in endemic areas. Mortality can be as high as 80% according to some reports. Although uncommon in Europe, and particularly in Spain, some cases are still seen mainly because of the increasing number of immigrants and visitors from endemic countries such as eastern United States of America, Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, east Asia, and Oceania.53 When HIV-infected individuals seek our care, histoplasmosis is present in disseminated form in 95%.54 The skin lesions arise as a result of hematogenous spread and onset generally occurs after the CD4+ cell count has fallen below 150 cells/μL.

Different strains of H capsulatum have been identified, in relation to whether the patient has AIDS or not. Reyes-Montes et al.55 isolated the following chain types from H capsulatum in Mexican patients with AIDS: EH-316, EH-317, EH-318, EH-319, EH-323, and EH-325. In contrast, EH-46 and EH-53 were isolated from patients without AIDS.

Whether or not sex is a risk factor for disease is still under debate. Some authors report that histoplasmosis affects men and women in equal measure whereas others have found predominance among men. There is little information about the incidence of histoplasmosis between different ethnic groups or races. However, many authors seem to agree that the features of the skin lesions may differ with race and endemic status of the region.

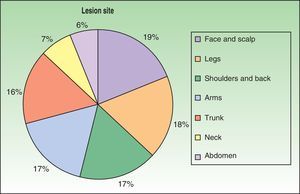

The first cases of disseminated histoplasmosis with skin involvement were reported by Bayes et al.56–59 Subsequently, other investigators reported further cases.60,61 After reviewing the literature, we found that the most common sites for lesions, in decreasing order, were the face and scalp, legs, shoulders and back, trunk, neck, and abdomen9,16,17,57–62 (Fig. 15). However, Bonifaz and Chang63 found that lesions occur mainly on the face and trunk. Cutaneous lesions are present in 38% to 85% of cases, according to whether patients are originally from South America or Africa, suggesting that genetic differences are present in these 2 variants. It has been suggested that dermotropic strains of H capsulatum may be responsible for the higher frequency of skin lesions in patients with AIDS. H capsulatum has been found in endoneural macrophages and in Schwann cells in cutaneous nerves. It is thought that a large number of these microorganisms invade the dermis, with secondary nerve infection then occurring although affected nerves do not show necrosis or cell proliferation. The presence of fungal elements in cutaneous nerves could be the main indicator of recurrent disease or dissemination. Mucosal lesions such as papules, nodules, and ulcers may occur in the gastrointestinal tract.

Bonifaz and Chang63 found papules, nodules and hyperkeratotic plaques, some ulcers, and purpuric lesions in all their patients. This clinical presentation occurs frequently and had been reported previously in populations in Latin America.12,64 Samples taken by curettage of these lesions lead to confirmation of the diagnosis of mycosis in almost all cases.64

Of note is that primary prophylaxis (itraconazole, 200mg/d) is administered to HIV-positive patients with a CD4+ count less than 150 cells/μL. A mortality rate of 43.5% has been reported in patients with disease that has become disseminated despite treatment,8 whereas in a recent European review this figure was 15% in the initial phases of treatment and 57% during follow-up.65

Coccidioidomycosis is a systemic mycosis found in America. The disseminated form is most common in men and in patients with AIDS and with dark skin. The course of infection may be acute, subacute, or chronic. In the subacute and chronic forms, most symptoms are localized to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, osteoarticular system, lymph nodes, and the CNS.

The primary pulmonary form manifests as pneumonia (in 44%) and miliary involvement may be present (in 19%). Cavitation or coccidioidomas may also be present (in 19%).21,22,66 In approximately 0.2% of patients with primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, the lesions spread predominantly to the skin, CNS, and osteoarticular system. The disseminated form generally follows an acute course, reaching various organs and systems and rapidly leading to death if diagnosis and treatment are delayed. The first report of HIV-associated coccidioidomycosis in Spain appeared in 1997.67 Approximately 10% to 20% of HIV-positive patients with systemic infection have cutaneous lesions, which provide a defining characteristic of AIDS and are a sign of poor prognosis. Early detection of these lesions can lead to early start of ART and so improve the prognosis.66

The large number of clinical forms and possible complications make it difficult to indicate specific treatment regimens for every situation. Recently, in cases refractory to treatment, voriconazole and posaconazole have been suggested for their broad spectrum of action, but outcomes have not been very satisfactory.68

Although vaccines against coccidioidomycoses have been under investigation for years, none as yet has proven effective. Vaccines based on total RNA extracted from spherules have been shown to be ineffective. However, in recent studies, recombinant antigens have shown promising results in animal models.18,42

Surgical resection of the lesion is indicated in cases of nodules in the lungs and at other sites when patients do not respond to antifungal therapy. Detection of a mass or abscess in the brain requires drainage or surgical resection. Debridement of cutaneous lesions to eliminate necrotic material is an important auxiliary measure. Patients should be treated in an outpatient setting, with follow-up at 3 and 6 months, then annually for a further 12 years.32

The virulence of the Cryptococcus genus is related to protease and oxidase production as well as the antiphagocytic properties of the capsular polysaccharide. The most plausible explanation for infection is the small diameter of the basidiospores (1.2–1.8μm), which allows them to accumulate in the alveoli, where the encapsulated yeasts are transformed at a temperature of 37°C. In most cases, inhalation of Cryptococcus species causes asymptomatic and self-limiting pulmonary infection, and yeasts can remain latent in the pulmonary environment or die. If an immunocompromised state develops subsequently, they may become reactivated and cause disease.69 Several studies have shown that C neoformans molecular type VNI is predominant in HIV-positive patients whereas C gattii molecular type VGII is predominant in HIV-negative ones (P<.001). Only 3 out of 37 cases in HIV-positive patients (8.1%) were caused by C gattii molecular type VGII, whereas 5 of 21 cases in HIV-negative patients (23.8%) were caused by C neoformans molecular type VNI.70–72

Before ART became available, cryptococcosis had become a major opportunistic infection and the leading cause of death in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ counts below 100cells/μL.5,43 In Spain, cryptococcosis was the most common fungal infection in these patients as of 2006.73

Skin infection in cryptococcosis occurs in 10% to 20% of cases, almost always secondary to systemic infection and so is considered a “sentinel sign” of disseminated disease. Necrotizing infections in soft tissues (cellulitis and necrotizing fascitis) and lesions that resemble pyoderma gangrenosum and keloid scars have occasionally been reported. Mortality is high (80%).74,75

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is a very rare condition, defined in the literature by the identification of C neoformans in a skin biopsy or culture in absence of disseminated disease. The sporotrichotic pattern is an extremely uncommon presentation. The patients in the cases we reviewed were immunocompromised but were not infected with HIV.76

The use of primary prophylaxis is still under discussion. In a metaanalysis of primary prophylaxis with fluconazole or itraconazole in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ counts below 300 cells/μL, the incidence of cryptococcosis decreased but mortality was unaffected. In patients with HAART-induced immune reconstitution, fluconazole or itraconazole can be interrupted provided the CD4+ count has remained stable above 100 cells/μL over the last 12 months.77,78

ConclusionsSystemic mycoses are mainly pulmonary diseases caused by dimorphic pathogenic fungi. If the inoculum is large or the individual's immune system is compromised, primary infection is possible and may be acute, self-limiting, or subclinical. Most skin manifestations correspond to disseminated disease, and so systemic treatment is required. Given that other skin lesions may also develop in the course of these diseases, it is recommended to take an extensive medical history and perform additional imaging tests, accompanied by histopathologic study and culture.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, Arenas R, Moreno-Coutiño G, Vásquez E, Fernández R, Chang P. Micosis sistémicas en pacientes con virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana/sida. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:5–17.