Colombia is home to one of the areas with the highest levels of exposure to UV radiation in the world, namely, the Andes Mountains, which stretch along the equator. Recent studies have reported an increase in the incidence of basal cell carcinoma in Colombia, but the risk factors associated with the development of this disease have not been studied.

ObjectiveTo determine the risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in patients from the National Dermatology Center of Colombia.

Material and methodsWe performed a case-control study involving 406 individuals, and analyzed sociodemographic, epidemiological, and clinical factors using multiple logistic regression.

ResultsThe following risk factors were identified: skin phototypes I to III (odds ratio [OR], 15.4), family history of skin cancer (OR, 5.8), past history of actinic keratosis (OR, 3.3), continued residence in a rural area after the age of 30 years (OR, 2.96), practice of outdoor sports (OR, 2.67), history of 10 or more episodes of sunburn (OR, 2.3), actinic conjunctivitis (OR, 2.26), and failure to use a hat in childhood (OR, 2.11).

ConclusionsDifferent factors specific to Colombia increase the risk of basal cell carcinoma. In particular, the association with phototype III could partly explain the increase in incidence detected in this country. Preventive programs should target the risk groups detected and highlight the importance of basing decisions on local evidence.

Sobre el paralelo ecuatorial, en la cordillera de los Andes, se localiza una de las áreas con la radiación ultravioleta más alta del planeta. Colombia se encuentra en esta ubicación, y recientemente se ha documentado para este país un incremento en las tasas de carcinoma basocelular; sin embargo no se han estudiado en esta población los factores asociados con el desarrollo de esta neoplasia.

ObjetivoEstablecer factores de riesgo de carcinoma basocelular en pacientes del Centro Nacional de Dermatología de Colombia.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio de casos y controles, incluyendo 406 sujetos. Se estudiaron factores sociodemográficos, epidemiológicos y clínicos. Para el análisis se empleó el método de regresión logística.

ResultadosSe identificaron los siguientes factores de riesgo: fototipos I al III (OR: 15,4), antecedente familiar de cáncer de piel (OR: 5,8), antecedente de queratosis actínicas (OR: 3,3), vivir en área rural incluso después de los 30 años (OR: 2,96), practicar deportes al aire libre (OR: 2,67), historia de 10 o más quemaduras solares (OR: 2,3), conjuntivitis actínica (OR: 2,26), y no utilizar sombrero en la infancia (OR: 2,11).

ConclusiónExisten diferentes factores propios del contexto colombiano que incrementan el riesgo de carcinoma basocelular. Se destaca la asociación con el fototipo III, que podría explicar parte del fenómeno de incidencia creciente en el país. Las acciones preventivas se deben enfocar a los grupos de riesgo detectados, resaltando la importancia de tomar decisiones basadas en la evidencia local.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignant tumor in white individuals and its incidence is growing in different parts of the world.1–3 Two studies have reported similar patterns in the incidence of this disease in Colombia. The first, published in 2007 and conducted at the Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta E.S.E, described an increase from 40 cases per 10 000 patients in 2003 to 110 cases per 10 000 patients in 2005.4 The second study, published by Sánchez et al.5 in 2011, reported an increase from 23 cases per 100 000 inhabitants in 2003 to 41 cases per 100 000 inhabitants in 2007.5 According to Sánchez et al., if the current trend continues and conditions remain unchanged, the incidence of BCC could reach worrying levels from the perspective of the health care system, with an estimated 102 new cases per 100 000 inhabitants in 2020.

Skin cancer has not been a public health priority in Colombia, partly because of its low mortality (approximately 1 death per 100 000 population per year).6,7 According to reports from other countries, however, skin cancer is a major public health burden in terms of mortality and health costs. Based on data from the US social insurance program, Medicare, skin cancer costs over US $426 million a year, placing it among the 5 most costly cancers in the United States.8 In England, according to data published in 2009, skin cancer cost the National Health Service an estimated £190 million in 2002.9

It is widely established that UV radiation is involved in the genesis of BCC through a complex interplay of factors, such as duration and frequency of exposure. While UV-B radiation causes direct DNA damage, UV-A radiation induces photo-oxidative stress and mutations through the generation of oxygen reactive species.10,11 Columbia lies in the equatorial region (latitude 0°), which is exposed to some of the highest levels of UV radiation in the world.12 Furthermore, a large proportion of the country's population lives in the Andean region, at an average altitude of 2400m above sea level. The population is also characterized by a unique racial makeup and a specific socioeconomic context, which, if it changed, could modify the true risk of BCC in the Colombian population.

Very few studies have analyzed the risk of BCC in Latin America. In view of the rising incidence of this disease in Colombia5 and the fact that the country's population is exposed to risk factors that may differ in distribution from those in countries with distinct geographical and cultural characteristics, we decided to perform a case-control study to establish the main risk factors for BCC in a sample of patients from the national referral center for skin diseases in Colombia.

Material and MethodsWe performed an analytical case-control study at the Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta E.S.E, where we consecutively enrolled all patients newly diagnosed with histologically confirmed BCC in 2010. Each case was matched to a control of the same age (±3 years), and measures were taken to control for the possible confounding effect of age. The controls were recruited from among patients from the same center without neoplastic disease or lesions indicative of skin cancer on physical examination. We excluded patients who had been prescribed routine protection against UV radiation due to an underlying condition such as photodermatosis.

The sample size was calculated to detect a difference in skin sensitivity to UV radiation between cases and controls similar to that reported by Vlajinac et al.,13 who observed a frequency of sensitivity of 39% for cases and 23% for controls. We calculated a sample size of 386 (193 cases and 193 controls) using the formula designed by Miettinen and modified by Connor,14 with a statistical power of 80% and a 95% confidence level. The questionnaire used to assess risk factors for BCC was drawn up following a systematic review of the literature and input from a panel of experts from the study center and tested for reliability to ensure its reproducibility. Questions with the highest levels of reliability were included in the final questionnaire, which addressed issues such as sociodemographic variables, place of residence, occupational and recreational exposure to UV radiation, personal and family history, and clinical aspects. A standardized Fitzpatrick scale15 was used by the study investigators to classify participants by phototype. The study was assessed and approved by an independent ethics committee and conducted in accordance with national and international guidelines (revised Declaration of Helsinki [2000]); all the cases and controls gave their written consent to participate in the study.

The statistical analysis included a general description of variables based on the scales used to measure each variable. A bivariate analysis using the χ2 test was performed to investigate dependent or independent associations between variables, with calculation of odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% CIs. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. For each variable, we defined a reference category that did not include the attribute being analyzed. Table 1 shows a summary of the ORs and 95% CIs calculated for each risk factor; categories with an OR of 1 (no association) were not included. We compared the means and medians of continuous variables, which were then reclassified as categorical variables to calculate the ORs. Finally, we performed multivariate analysis with conditional logistic regression and included variables with statistically significant results, clinically relevant variables, and possible confounders. The goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using the Hosmer Lemeshow test. Analyses were performed using the statistical program Stata 10.

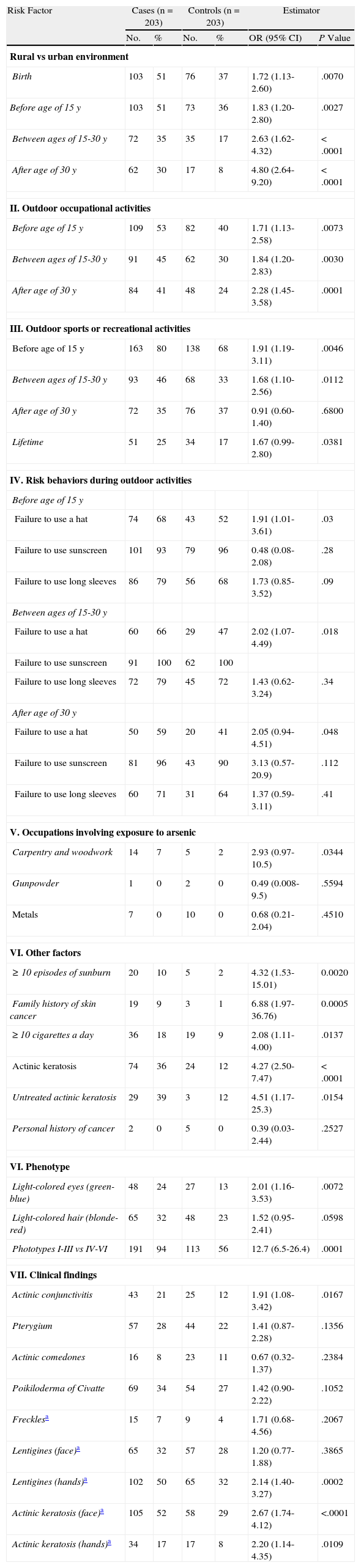

Risk Factors for Basal Cell Carcinoma: Bivariate Analysis With Odds Ratios (ORs).

| Risk Factor | Cases (n=203) | Controls (n=203) | Estimator | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Rural vs urban environment | ||||||

| Birth | 103 | 51 | 76 | 37 | 1.72 (1.13-2.60) | .0070 |

| Before age of 15 y | 103 | 51 | 73 | 36 | 1.83 (1.20-2.80) | .0027 |

| Between ages of 15-30 y | 72 | 35 | 35 | 17 | 2.63 (1.62-4.32) | < .0001 |

| After age of 30 y | 62 | 30 | 17 | 8 | 4.80 (2.64-9.20) | < .0001 |

| II. Outdoor occupational activities | ||||||

| Before age of 15 y | 109 | 53 | 82 | 40 | 1.71 (1.13-2.58) | .0073 |

| Between ages of 15-30 y | 91 | 45 | 62 | 30 | 1.84 (1.20-2.83) | .0030 |

| After age of 30 y | 84 | 41 | 48 | 24 | 2.28 (1.45-3.58) | .0001 |

| III. Outdoor sports or recreational activities | ||||||

| Before age of 15 y | 163 | 80 | 138 | 68 | 1.91 (1.19-3.11) | .0046 |

| Between ages of 15-30 y | 93 | 46 | 68 | 33 | 1.68 (1.10-2.56) | .0112 |

| After age of 30 y | 72 | 35 | 76 | 37 | 0.91 (0.60-1.40) | .6800 |

| Lifetime | 51 | 25 | 34 | 17 | 1.67 (0.99-2.80) | .0381 |

| IV. Risk behaviors during outdoor activities | ||||||

| Before age of 15 y | ||||||

| Failure to use a hat | 74 | 68 | 43 | 52 | 1.91 (1.01-3.61) | .03 |

| Failure to use sunscreen | 101 | 93 | 79 | 96 | 0.48 (0.08-2.08) | .28 |

| Failure to use long sleeves | 86 | 79 | 56 | 68 | 1.73 (0.85-3.52) | .09 |

| Between ages of 15-30 y | ||||||

| Failure to use a hat | 60 | 66 | 29 | 47 | 2.02 (1.07-4.49) | .018 |

| Failure to use sunscreen | 91 | 100 | 62 | 100 | ||

| Failure to use long sleeves | 72 | 79 | 45 | 72 | 1.43 (0.62-3.24) | .34 |

| After age of 30 y | ||||||

| Failure to use a hat | 50 | 59 | 20 | 41 | 2.05 (0.94-4.51) | .048 |

| Failure to use sunscreen | 81 | 96 | 43 | 90 | 3.13 (0.57-20.9) | .112 |

| Failure to use long sleeves | 60 | 71 | 31 | 64 | 1.37 (0.59-3.11) | .41 |

| V. Occupations involving exposure to arsenic | ||||||

| Carpentry and woodwork | 14 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2.93 (0.97-10.5) | .0344 |

| Gunpowder | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.49 (0.008-9.5) | .5594 |

| Metals | 7 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0.68 (0.21-2.04) | .4510 |

| VI. Other factors | ||||||

| ≥10 episodes of sunburn | 20 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 4.32 (1.53-15.01) | 0.0020 |

| Family history of skin cancer | 19 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 6.88 (1.97-36.76) | 0.0005 |

| ≥10 cigarettes a day | 36 | 18 | 19 | 9 | 2.08 (1.11-4.00) | .0137 |

| Actinic keratosis | 74 | 36 | 24 | 12 | 4.27 (2.50-7.47) | <.0001 |

| Untreated actinic keratosis | 29 | 39 | 3 | 12 | 4.51 (1.17-25.3) | .0154 |

| Personal history of cancer | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0.39 (0.03-2.44) | .2527 |

| VI. Phenotype | ||||||

| Light-colored eyes (green-blue) | 48 | 24 | 27 | 13 | 2.01 (1.16-3.53) | .0072 |

| Light-colored hair (blonde-red) | 65 | 32 | 48 | 23 | 1.52 (0.95-2.41) | .0598 |

| Phototypes I-III vs IV-VI | 191 | 94 | 113 | 56 | 12.7 (6.5-26.4) | .0001 |

| VII. Clinical findings | ||||||

| Actinic conjunctivitis | 43 | 21 | 25 | 12 | 1.91 (1.08-3.42) | .0167 |

| Pterygium | 57 | 28 | 44 | 22 | 1.41 (0.87-2.28) | .1356 |

| Actinic comedones | 16 | 8 | 23 | 11 | 0.67 (0.32-1.37) | .2384 |

| Poikiloderma of Civatte | 69 | 34 | 54 | 27 | 1.42 (0.90-2.22) | .1052 |

| Frecklesa | 15 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 1.71 (0.68-4.56) | .2067 |

| Lentigines (face)a | 65 | 32 | 57 | 28 | 1.20 (0.77-1.88) | .3865 |

| Lentigines (hands)a | 102 | 50 | 65 | 32 | 2.14 (1.40-3.27) | .0002 |

| Actinic keratosis (face)a | 105 | 52 | 58 | 29 | 2.67 (1.74-4.12) | <.0001 |

| Actinic keratosis (hands)a | 34 | 17 | 17 | 8 | 2.20 (1.14-4.35) | .0109 |

We analyzed 203 cases and 203 controls. The mean (SD) age in both groups was 65 (13.2) years and the median age was 66 years (range, 30-97 years). The age differences between the groups were not significant (P=.96). Sixty-one percent of the cases and 65% of the controls were women (P=.3). The mean level of education was similar between the groups (8.6 years for cases vs 8.4 for controls, P=.07). No significant differences were observed for district of birth (P=.17) or for the association between the risk of BCC and the average altitude at which the study participants had resided during their lifetime (P=.8).

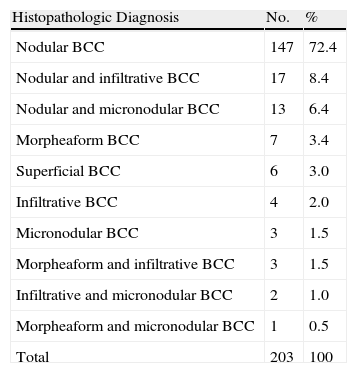

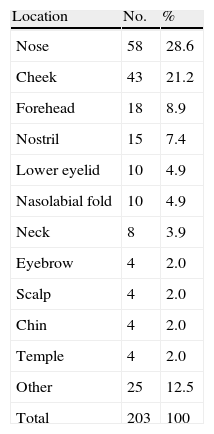

The most common histologic subtype was nodular BCC (72.4% of all cases) (Table 2) and the most common location was the nose (28.6% of all cases) (Table 3). The main diagnoses in the control group were tinea pedis (34%, 69/203), seborrheic dermatitis (24%, 48/203), contact dermatitis (19%, 38/203), rosacea (16%, 32/203), and psoriasis (7%, 16/203).

Histopathologic Subtypes of Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC).

| Histopathologic Diagnosis | No. | % |

| Nodular BCC | 147 | 72.4 |

| Nodular and infiltrative BCC | 17 | 8.4 |

| Nodular and micronodular BCC | 13 | 6.4 |

| Morpheaform BCC | 7 | 3.4 |

| Superficial BCC | 6 | 3.0 |

| Infiltrative BCC | 4 | 2.0 |

| Micronodular BCC | 3 | 1.5 |

| Morpheaform and infiltrative BCC | 3 | 1.5 |

| Infiltrative and micronodular BCC | 2 | 1.0 |

| Morpheaform and micronodular BCC | 1 | 0.5 |

| Total | 203 | 100 |

The crude odds ratios for the main risk factors analyzed are shown in Table 3. We investigated associations between the risk of BCC and lifetime residence in a rural area, lifetime outdoor occupational activities, and outdoor recreational activities before the age of 15 years and between the ages of 15 and 30 years. In our analysis of sun exposure behavior, we established that failure to use a hat during outdoor activities may constitute a risk practice. We also observed that only a small percentage of patients (0%-7%) had used sunscreen throughout their lives. We detected a significant association between the risk of BCC and having worked in the carpentry trade or wood industry (OR, 2.9; P=.03), but not for having worked in the gunpowder, metal, or insecticide industries.

We also detected significant associations between the risk of BCC and the following factors: history of 10 or more episodes of sunburn (OR, 4.32; P=.0020), family history of skin cancer (OR, 6.8; P=.0005), history of smoking an average of 10 or more cigarettes a day (OR, 2.08; P=.0122), history of actinic keratosis (OR, 4.27; P<.0001), and history of untreated actinic keratosis (OR, 4.51; P=.0154). No significant associations were observed for a personal history of other types of cancer (P=.257).

The main phenotype analyzed was skin sensitivity to UV radiation (phototype). Using phototypes IV to VI as the reference category, we observed that phototypes I, II, and III were all risk factors for BCC. The respective ORs (95% CI) were 17.5 (3.29-113.7), 15.6 (7.5-34.3), and 10.38 (5.08-22.4). Based on these results, we reclassified the phototypes into 2 categories: I-III and IV-VI. The corresponding risk estimates are shown in Table 1.

On examining risk related to phenotypic features and clinical findings, we found significant associations for light-colored (green-blue) eyes, actinic conjunctivitis, lentigines on the hands, and actinic keratosis on the hands or the face (Table 1).

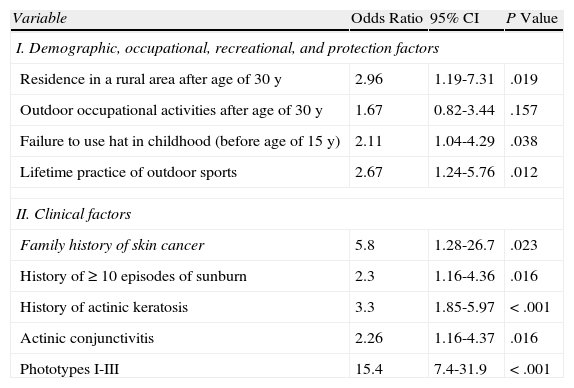

The conditional logistic regression model based on the results of the bivariate analysis showed the following factors to be clearly associated with a risk of developing BCC: residence in a rural area, particularly after the age of 30 years, failure to use a hat in childhood, practice of outdoor sports throughout one's life, a family history of skin cancer, a personal history of 10 or more episodes of sunburn, a history of actinic keratosis, clinical findings of actinic conjunctivitis, and phototypes I, II, and III. The corresponding risk estimates are shown in Table 4.

Risk Estimates of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Conditional Logistic Regression.a

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

| I. Demographic, occupational, recreational, and protection factors | |||

| Residence in a rural area after age of 30 y | 2.96 | 1.19-7.31 | .019 |

| Outdoor occupational activities after age of 30 y | 1.67 | 0.82-3.44 | .157 |

| Failure to use hat in childhood (before age of 15 y) | 2.11 | 1.04-4.29 | .038 |

| Lifetime practice of outdoor sports | 2.67 | 1.24-5.76 | .012 |

| II. Clinical factors | |||

| Family history of skin cancer | 5.8 | 1.28-26.7 | .023 |

| History of ≥10 episodes of sunburn | 2.3 | 1.16-4.36 | .016 |

| History of actinic keratosis | 3.3 | 1.85-5.97 | <.001 |

| Actinic conjunctivitis | 2.26 | 1.16-4.37 | .016 |

| Phototypes I-III | 15.4 | 7.4-31.9 | <.001 |

Despite the progressive increase in the incidence of skin cancer in Colombia,5 there are no known risk factors that are specific to the Colombian population. This might explain the lack of skin cancer prevention strategies in our country. The present study is the first to analyze risk factors for BCC in a sample of Colombian patients; the aim was to collect empirical evidence to support the design of a national skin cancer prevention program based on local evidence.

Although it has been well established that the UV radiation dose to which individuals are exposed increases notably with altitude,12 we found no significant differences between cases and controls in terms of risk of BCC and lifetime residence at a given altitude. This is probably because although all the cases had lived most of their lives at the foothills of the Andes Mountains (average altitude of 2400m above sea level), most of the controls, despite having being recruited from the national referral center for skin diseases, were from Bogotá (2600m above sea level).

The average level of education was similar in both groups (incomplete secondary education) and there were no significant differences in the number of years studied. This is possibly a reflection of the fact that approximately 80% of the patients treated at the Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta E.S.E are from a middle socioeconomic background (levels 2 and 3). This might have led to an unintentional matching of cases and controls in this respect and obscured the association between BCC and socioeconomic status. This possible bias could be confirmed in a population-based study analyzing the risk of BCC in individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

It is widely accepted that UV radiation is the most important risk factor for the development of BCC,10,12,13,16,17 hence the importance of analyzing exposure levels during outdoor occupational and recreational activities. One of the most important findings of the present study is the increased risk of BCC observed in individuals whose work obliges them to spend long hours outdoors. This risk was observed in all the age groups analyzed but it was particularly noticeable in individuals who continued to work outdoors after the age of 30 years. Eighty percent of the cases in our series who worked outdoors were employed in agriculture; this risk factor is important in Colombia, as agricultural activities still account for large sectors of the country's economy. We found significant differences between individuals who had lived in a rural environment and those who had lived in an urban environment for the different age groups analyzed. Interestingly, we observed that continued residence in a rural environment after the age of 30 years may be a strong risk factor for BCC (adjusted OR [aOR], 2.96). Rural residence is closely linked to occupational exposure, partly because there is an increased risk of midday sun exposure. Nevertheless, the increased risk detected in individuals living in rural environments may also be related to other factors such as poor access to prevention campaigns, health services, and the media. It has also been reported that rural residents may have an increased risk of skin cancer because they are less likely to use sunscreen and other protective measures.18 Findings such as these are important for Colombia because they highlight the need for mass-media campaigns targeting people in rural areas, who have the greatest risk of developing skin cancer.

Our results confirm the findings related to sun protection behaviors described by Sánchez et al.,19 who showed an almost complete failure to use sunscreen in both patients with BCC and controls during the early years of their lives, with only a slight improvement observed after the age of 30 years (6% in cases and 10% in controls). Our observation that failure to wear a hat in childhood was associated with an aOR of 2.11 highlights the importance of protective measures such as this, particularly in the early years of life.

Other studies have highlighted the importance of protection campaigns targeting children and adolescents, as there is a clear trend towards a lack of protective measures in these age groups; targeting these audiences is particularly important as they are dependent on their parents and educators.20–23We observed a significant risk of BCC associated with lifetime practice of outdoor sports (aOR, 2.67). This association has been reported in various studies,13,24,25 but our results are important in that they highlight the need for lifetime campaigns that start at school and emphasize the importance of using protective clothing and avoiding exposure to UV radiation during work or leisure activities at midday, when the risk is greatest.12

BCC is caused by different molecular alterations in DNA, mostly related to UV radiation–induced damage,26 but other factors, such as tobacco use, might also have a role in the complex process that leads to this cancer. However, studies similar to ours have failed to find evidence of a significant association between BCC and tobacco use.27,28 Our bivariate analysis showed that a history of smoking 10 or more cigarettes a day was significantly associated with a risk of BCC, but the association lost its significance when potential confounders such as phototype and working outdoors were added to the model (OR, 1.3; P=.42).

Other authors have reported that a history of severe or blistering sunburn might be associated with the development of BCC13,17,28; in our study we found a strong association between BCC and a history of sunburn (aOR, 2.3) on comparing individuals with fewer than 10 episodes of sunburn burns and those with 10 episodes or more. It is also therefore important to stress the importance of preventing sunburn, of any severity, throughout one's life. Again, campaigns describing protection strategies for children, who are particularly vulnerable, are needed.

Several findings in the physical examination may also be predictors of BCC.13,17,27 The most noteworthy findings in our study were the presence of actinic conjunctivitis (aOR, 2.26) and a history of actinic keratosis (aOR, 3.3); both indicate a history of chronic sun exposure and therefore individuals with either of these findings should be monitored as they are strong predictors of the development of BCC.

Several studies that have evaluated risk factors in skin cancer have suggested that skin sensitivity to UV radiation (specifically phototypes I and II) might be associated with the development of this disease.27,29 The fact that we found significant associations between the risk of BCC and phototypes I, II, and III are particularly relevant as the vast majority of Colombians have phototypes II or III.15 Several Latin American studies have reported conflicting results with respect to phototype. In Brazil, for example, Bariani et al.30 found that only 3.5% of cases of BCC occurred in individuals with phototype III, while in Argentina, Ruiz Lascano et al.28 suggested that phototype III might be a risk factor for BCC (OR, 10). In our opinion, individuals with phototype III are a high-risk group as they have a false sense of security due to the fact that they develop mild to moderate sunburn during initial exposures but then tan. Considering the latitude at which Colombia lies and the intensity of UV radiation that reaches the surface, individuals with phototype III—and their doctors—need to be made aware that this population is extremely vulnerable to BCC (crude OR, 10.38; aOR for phototypes I-III, 15.4) as their false sense of security leads them to engage in risk behaviors (e.g., sunbathing for long hours and failure to use sunscreen or protective measures such as hats, sunglasses, and long sleeves).

In summary, despite the limitations of our case-control design, the present study offers important findings related to specific risk factors for BCC in the Colombian population. Our results should be taken into account when designing health promotion and BCC prevention strategies. These strategies should prioritize rural regions, agricultural workers, and children, in whom we detected a low use of sun protection measures, probably because of their dependent status. Individuals with a family history of skin cancer, a history of numerous episodes of sunburn or of actinic keratosis or actinic conjunctivitis should also be targeted as they need to be monitored by dermatology specialists. Finally, Colombians with phototype III should also be a priority in prevention and monitoring programs as they are particularly vulnerable to sunburn because of their false sense of security.

FundingThe present study was performed with the logistical and financial support of Centro Dermatológico Federico Lleras Acosta E.S.E. in Bogotá, Colombia.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez G, et al. Factores de riesgo de carcinoma basocelular. Un estudio del Centro Nacional de Dermatología de Colombia. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2012;103:294-300.