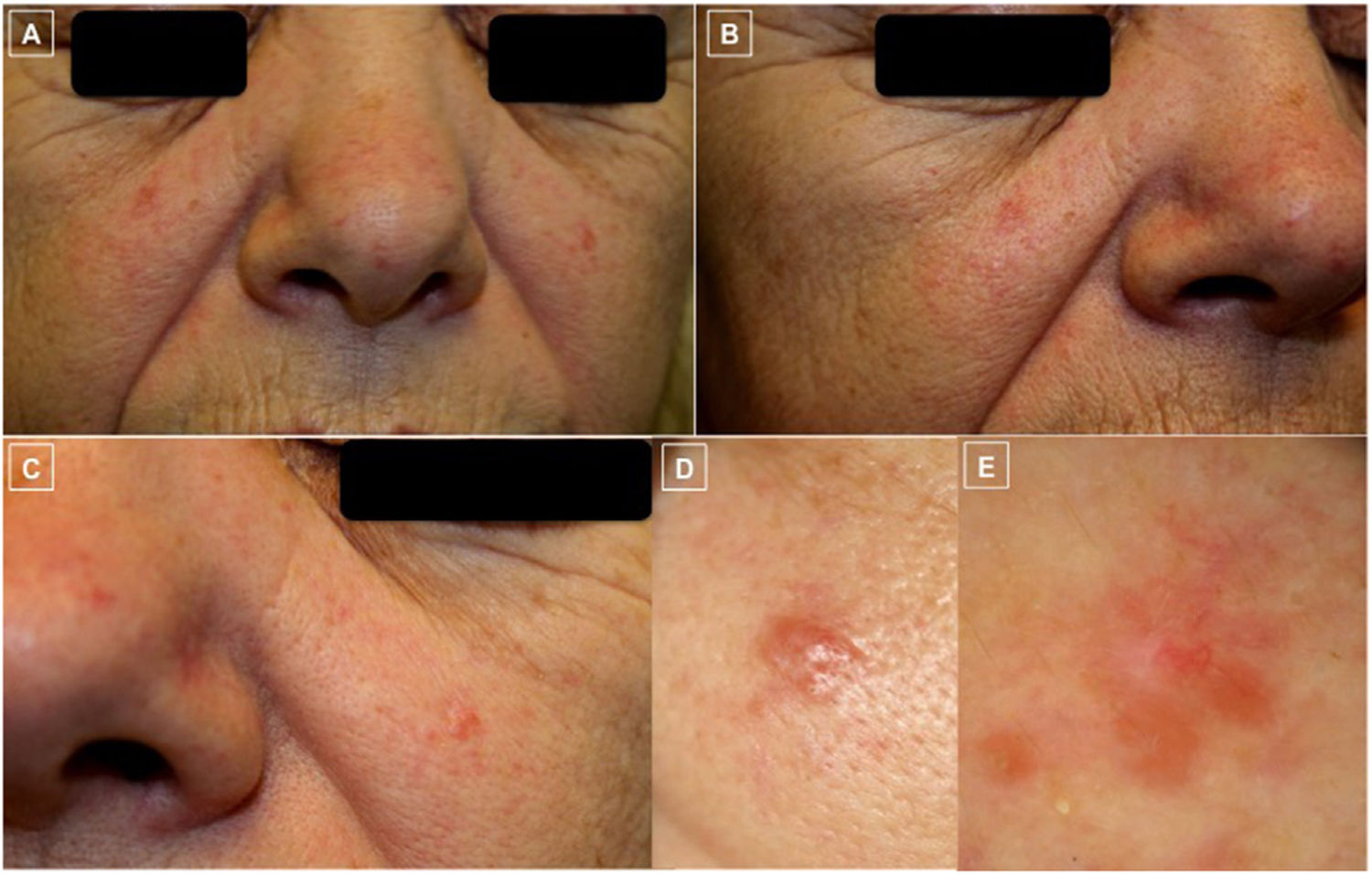

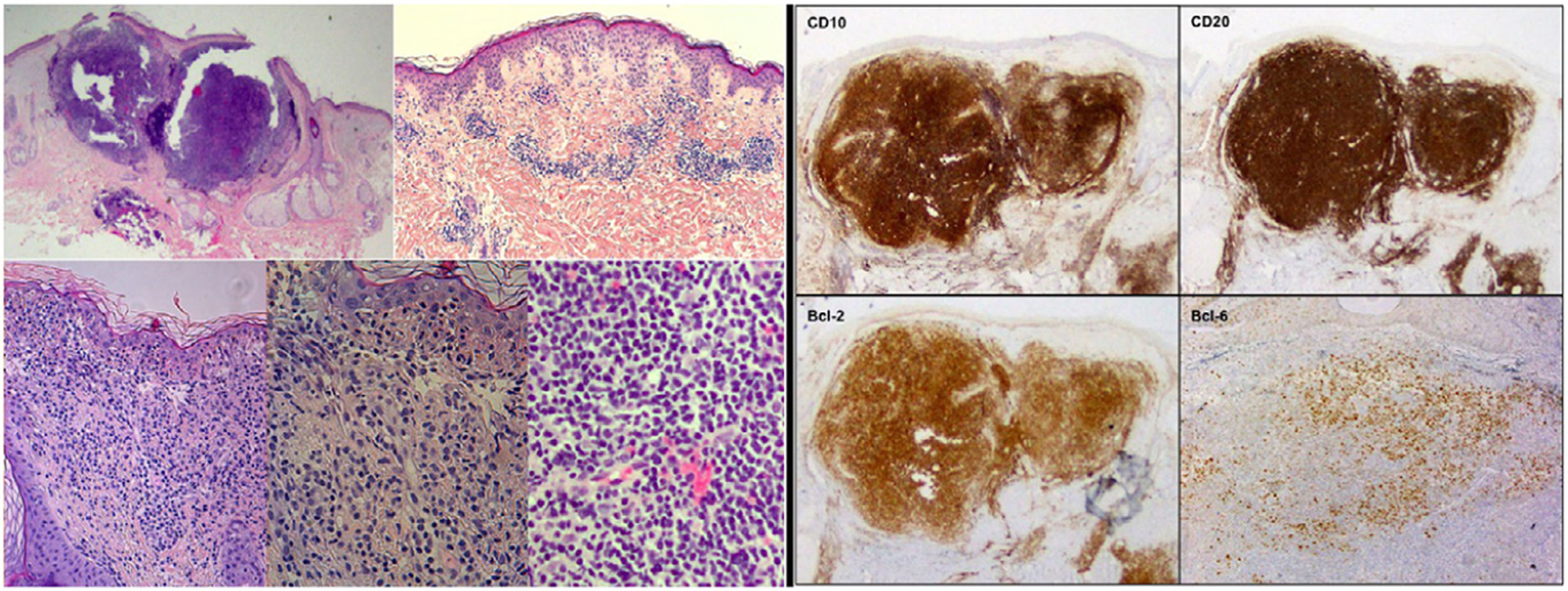

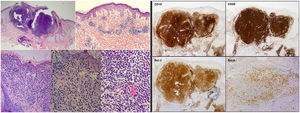

A 60-year-old woman with no past history of interest visited our dermatology clinic with multiple reddish lesions on both cheeks that had appeared a year earlier. Physical examination revealed disperse telangiectases and several erythematous-pink papules in the malar regions; one of the telangiectases was larger (6 × 5 mm) and it was decided to biopsy it (Fig. 1). Histopathology revealed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate located in the papillary and reticular dermis with a mixed nodular-diffuse growth pattern and cells with the appearance of centrocytes, together with other, slightly larger cells with the appearance of centroblasts (Fig. 2). Immune staining was positive for CD10, CD20, CD79a, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6, but negative for CD3 and cyclin D1 (Fig. 2).

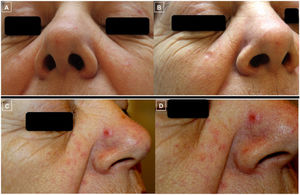

A-D, Clinical photographs. A-C, Clearly demarcated erythematous papules and disperse telangiectases on both cheeks and the tip of the nose. D, The largest papule, located on the left cheek was biopsied. E, Dermoscopic photograph corresponding to the previous lesion, showing, at the top, branching linear vessels on an unstructured salmon-colored area and the occasional whiteish region.

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of the skin biopsy. On the left, hematoxylin–eosin (H-E) staining with images from smallest to largest magnification under an optical microscope, showing the histological characteristics of cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma: lymphocyte infiltrate located in the middle and deep dermis with a mixed (nodular/diffuse) growth pattern and presence of cells of centrocytic and centroblastic appearance. On the right, immune-staining panel compatible with primary cutaneous center follicle lymphoma. The panel shows positive staining for CD10, CD20, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6 (hematoxylin–eosin, x2, x4, x10, x20, x20; IHQ, x2, x2, x2, x4).

Furthermore, monoclonal rearrangement of the gene IgH was detected using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and rearrangement of the gene Bcl-2 was detected using FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization). Flow cytometry was normal. An initial staging was performed using computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, and blood tests were carried out, including lactate dehydrogenase, but no evidence of systemic disease was found. The findings were thus compatible with primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma (PCFCL), which was confirmed following absence of systemic disease after 6 months. A bone-marrow biopsy was not performed due to the painless course of this disease and to the results of the additional tests.

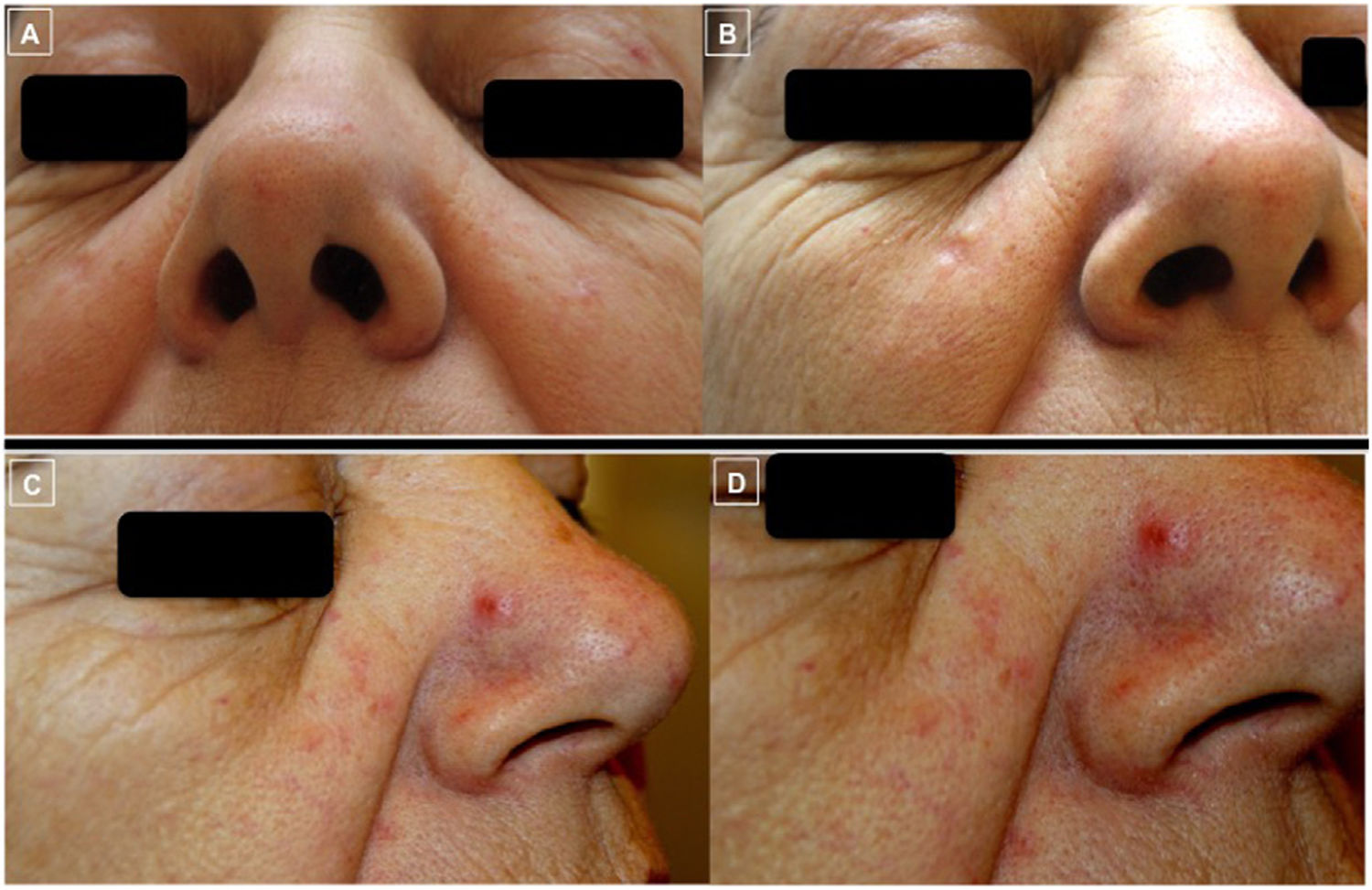

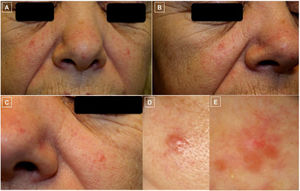

Treatment consisted of intralesional rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) on 6 occasions, with a good response (Figs. 3A and 3B). The patient subsequently developed a new erythematous papule on the side of the nose (Figs. 3C and 3D), which, together with the tendency of the patient’s skin toward redness and the presence of disperse telangiectases, produced a a rosaceiform appearance. Topical treatments such as metronidazole and ivermectin were therefore used. Given the lack of response, a new biopsy was taken, which revealed histopathologic findings compatible with PCFCL. The lesions were again treated with intralesional rituximab, a malar lesion and a lesion on the internal occular surface were surgically excised, and complete remission was observed. A watch-and-wait approach was subsequently adopted despite the appearance of new lesions. The patient is currently in joint follow-up with the dermatology and hematology departments, with persistent multiple facial lesions and no extracutaneous involvement.

Clinical photographs showing the course of the lesions (A-D). Photographs A and B show the good response of the lesions on both cheeks following treatment with intralesional rituximab. Photographs C and D, however, show worsening and the appearance of a clearly demarcated erythematous papule on the side of the nose (D) on skin with a tendency to redness and presence of telangiectases on the cheeks and tip of the nose, giving a rosaceaform appearance.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (PCBL) is a B-cell lymphoma that affects the skin with no signs of extracutaneous disease on diagnosis or in the following 6 months.1 According to records, the follicle center subtype (PCFCL) is the most common form of PCBL, together with primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.2 Both lymphomas present a painless chronic course, which leads to an approximate 5-year survival rate of ≥95%.1–4

Clinically, PCFCL presents firm, asymptomatic papules, plaques, or tumors, in isolation or in erythematous groups, predominantly on the head, neck, and torso.1,5–7 According to the bibliography described, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder may mimic a rosacea, although these are extremely rare cases.1,5–7 In 2012, Barzilai et al5 recorded 4 cases and in 2004, Seward et al7 contributed 1 further case, all of which were PCFCL with rosacea or rhinophyma-like clinical lesions. In 2011, Massone et al7 recorded a further 9 cases of PCFCL characterized by miliary or agminated lesions clinically compatible with rosacea.

Diagnosis of PCBL is based on histologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic findings.1,5 Classically, the lack of expression of Bcl-2 and of the t(14;18) chromosome translocation favors a diagnosis of PCFCL.1,3,4 Recent studies, however, show variable rates of positivity for expression of Bcl-2 (0%-86%) and t(14;18) in PCFCL. These include a retrospective comparative study8 that reports positive expression of Bcl-2 in 69% of cases of PCFCL and of t(14;18) in 9.1% of cases. Furthermore, the authors suggest that strong immune staining of Bcl-2 may be a predictor of the systemic nature of the disease.8 Thus, in light of these findings, it is necessary to achieve a staging that excludes systemic disease, and this should be maintained for at least 6 months to reach a definitive diagnosis of PCFCL.

With regard to treatment, we lack randomized clinical trials that allow us to establish clear evidence-based recommendations.9 In solitary or isolated lesion, the use of radiation therapy is recommended; otherwise, in small, clearly demarcated lesions, surgical excision is recommended.9 More disperse lesions may be treated with radiation therapy; nevertheless, in light of the chronic, painless course and the frequent recurrences of PCFCL, a watch-and-wait approach may be adopted.9 Intralesional rituximab is another option to consider.4,9,10 When the lesions are extensive, systemic rituximab is the treatment of choice, and chemotherapy (R-COP, R-CHOP) should be reserved for exceptional cases of extracutaneous disease or lack of response to rituximab in patients with progressive disease.9

In summary, PCFCL may mimic a granulomatous rosacea. The differential diagnosis of papulonodular eruptions on the face should therefore include B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, as well as adnexal tumors such as basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, and sebaceous hyperplasia, and inflammatory dermatoses such as sarcoidosis and cutaneous lupus. Knowledge of the clinical variability of PCFCL will facilitate early diagnosis and subsequent treatment, where necessary.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the patient, whose images are shown in our study, for providing written permission to publish those images.

Please cite this article as: Sarriugarte Aldecoa-Otalora J, Mitxelena Eceiza J, Córdoba Iturriagagoitia A, Viguria Alegría MC. Pápulas rojizas centrofaciales. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:668–670.