We report 2 cases of cytokeratin-20 negative neuroendocrine tumors with skin involvement that were not Merkel cell carcinoma.

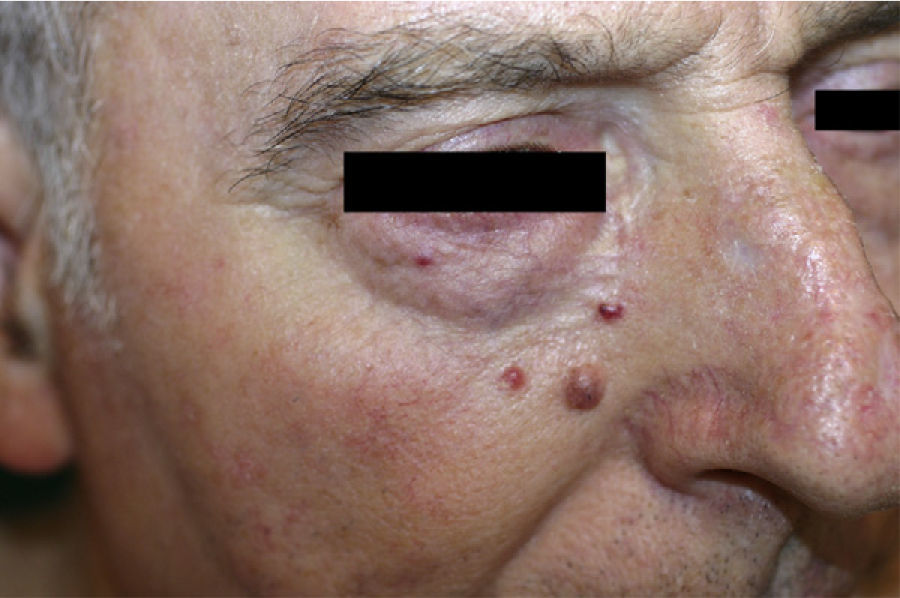

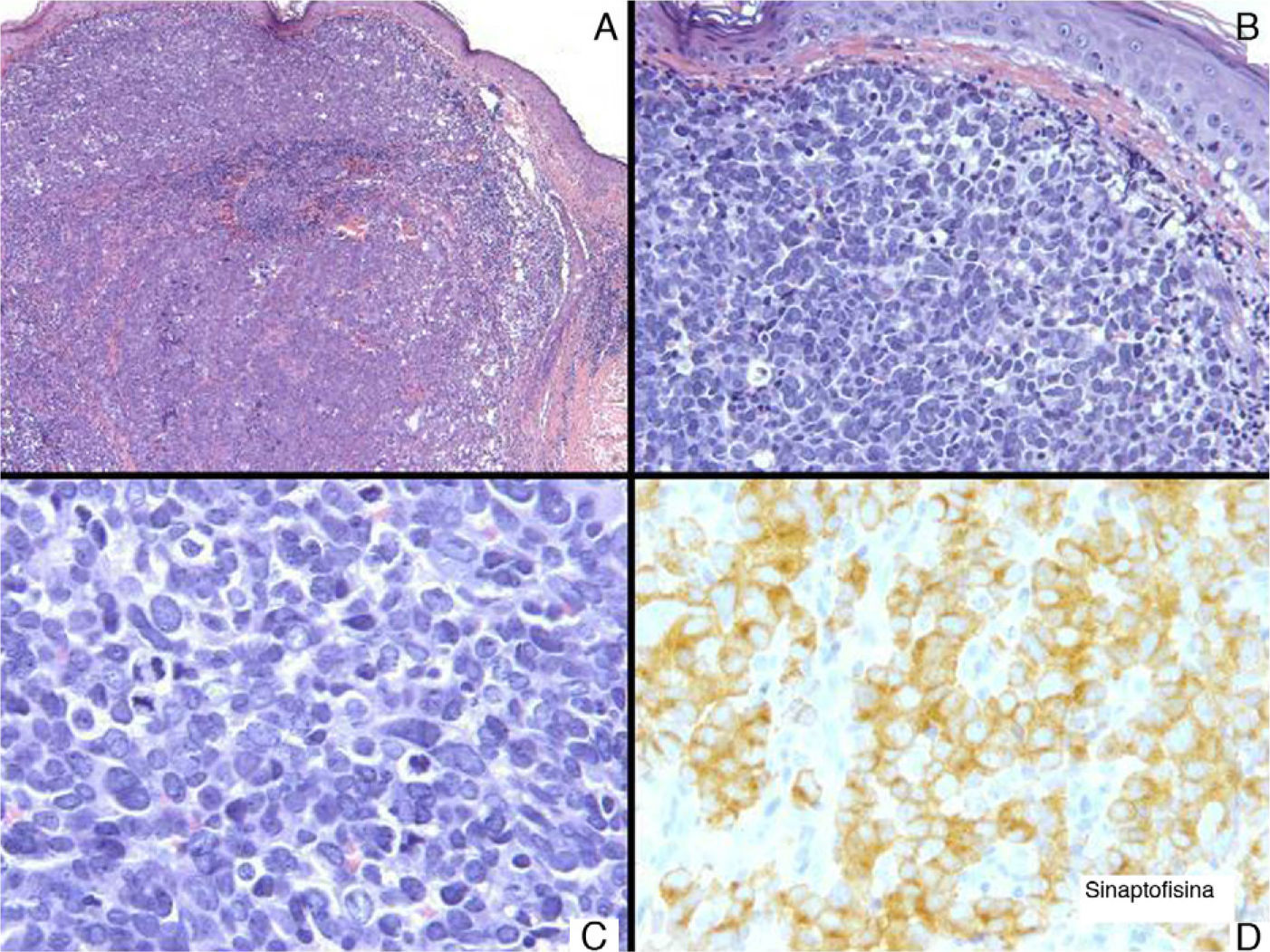

Patient 1. Patient 1 was a 72-year-old man with 3 asymptomatic papular, erythematous lesions measuring 2 to 3mm in the right paranasal region (Fig. 1). The lesions had appeared 20 days earlier. One of the lesions was excised to reveal a diffuse epithelial tumor consisting of solid nests of irregular, atypical polygonal cells with abundant mitotic figures. There was no sign of morphologic differentiation and the epidermis was not involved. The tumor was composed of keratin cells positive for AE1-AE3, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and neuron-specific enolase and negative for cytokeratin 20, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD30, S100, and human melanoma marker (HMB45) (Fig. 2). The tumor was diagnosed as intradermal carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation. Plasma levels of chromogranin A were elevated (124.2 ng/mL; normal range, 19.4-98.1mg/mL). Other hormones were normal in both blood and urine. Chest radiography, abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, 111In-labeled octreotide scintigraphy and positron electron imaging findings were normal. There were no significant findings in gastroscopy and colonoscopy revealed an adenomatous polyp. The 3 lesions were excised without any adjuvant therapy and chromogranin A levels returned to normal.

A, Tumor consisting of nests of polygonal cells (hematoxylin-eosin [H-E], original magnification ×5). B, These cells were irregular and atypical and there was no epidermal involvement (H-E, original magnification ×20). C, Abundant mitotic figures are apparent (H-E, original magnification ×40). D, These cells were positive for synaptophysin (H-E, original magnification ×40).

The patient has remained asymptomatic during 5 years of follow-up.

Patient 2. Patient 2 was a 62-year-old woman with a progressively growing sternal lesion that had appeared 2 years earlier. Examination revealed an erythematous-violaceous plaque measuring 3×2cm (Fig. 3). In the biopsy, a tumor was detected in the dermis in the form of disperse nests of monomorphic cells of epithelial appearance and few atypical cells. They had a poorly defined cytoplasm with occasional microcalcifications and limited mitotic activity. These cells were positive for AE1-AE3 keratins, cytokeratin 8, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and neuron-specific enolase and negative for S100, MELAN-A, HMB45, and cytokeratin 20. Histologic diagnosis was of cutaneous metastasis of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. Elevated levels of plasma somatostatin were found (27.3pmol/L; normal range, <16pmol/L). Other hormones were normal in both blood and urine. In view of a suspected diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of a somatostatin-secreting neuroendocrine tumor, octreotide scintigraphy was performed. Uptake was detected in the sternal region and the left axilla. In the other imaging tests, the only finding of note was biliary lithiasis and a hepatic lesion suggestive of hemangioma.

The sternal plaque was excised and 10 left axillary lymph nodes were dissected but no tumor infiltration was observed in any of these. After this procedure, somatostatin levels decreased to 19.9pmol/L (a decrease of 16pmol/L) but did not return to normal. Repeat octreotide scintigraphy still showed focal uptake in the upper external quadrant of the left breast, that is, the tail of the breast. Magnetic resonance imaging, X-ray radiography, and a breast ultrasound were requested to identify this lesion. The results were interpreted as corresponding to an intramammary lymph node measuring 9mm. On review of the patient's medical records, we found that a mammography had detected a lesion of 4mm in the same place 16 years earlier. At the time, benign lymph node enlargement had been diagnosed.

Under radiographic guidance, the lesion was excised to reveal infiltration by fibroadipose and lymph node tissue from a carcinoma of neuroendocrine origin. After excision, somatostatin levels returned to normal during the 2-year follow-up. During this time, the patient remained asymptomatic with no new lesions or increased uptake in octreotide scintigraphy.

Cutaneous neuroendocrine tumors can originate from many different organs. They are usually Merkel cell tumors. Cutaneous metastasis of endocrine tumors and primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumors of other origins are rare.1–4 These latter 2 types of tumor have certain neuroendocrine markers in common, such as synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin, and are negative for cytokeratin 20.5,6

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, hormone levels, and imaging. Of particular importance among the imaging tests is 111In-labeled octreotide scintigraphy. Octreotide is an analogue of somatostatin, and given that somatostatin receptors are expressed in most of these tumors, this test can detect between 67% and 91% of tumors. The technique can be used for diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of these patients.7,8 Some tumors may follow an aggressive course, although most are slow-growing and indolent.1

The main tumors to be included in the differential diagnosis are basal cell carcinoma and cutaneous lymphoma. Histologically, small cell tumors such as metastases from undifferentiated small cell carcinomas of the pulmonary oat cell carcinoma type and small cell neuroendocrine tumors such as Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and low-grade lymphomas should also be considered. Merkel cell carcinomas differ from neuroendocrine carcinomas with secondary cutaneous involvement in that their cells have basophilia and less cytoplasm, and often infiltrate the epidermis in the form of Bowen disease.

The treatment of choice for neuroendocrine tumors, whether or not there is cutaneous involvement, is surgery and indeed surgery is the only curative treatment.1

We reported 2 cases of neuroendocrine tumors with cutaneous involvement. In neither case did we find a primary neuroendocrine tumor at another site, though this does not mean that one might not be present because, for example, such a tumor might be too small to be detected in the imaging tests or endoscopy, as is the case with duodenal neuroendocrine tumors.9 Multidisciplinary study and long-term follow-up are therefore important with these patients.10

Please cite this article as: Arrue I, Arregui MA, Catón B, Soloeta R. Tumor neuroendocrino: descripción de 2 casos de evolución atípica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:94–96.

![A, Tumor consisting of nests of polygonal cells (hematoxylin-eosin [H-E], original magnification ×5). B, These cells were irregular and atypical and there was no epidermal involvement (H-E, original magnification ×20). C, Abundant mitotic figures are apparent (H-E, original magnification ×40). D, These cells were positive for synaptophysin (H-E, original magnification ×40). A, Tumor consisting of nests of polygonal cells (hematoxylin-eosin [H-E], original magnification ×5). B, These cells were irregular and atypical and there was no epidermal involvement (H-E, original magnification ×20). C, Abundant mitotic figures are apparent (H-E, original magnification ×40). D, These cells were positive for synaptophysin (H-E, original magnification ×40).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/15782190/0000010500000001/v1_201401220123/S1578219013002771/v1_201401220123/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w9/t1/zx4Q/XH5Tma1a/6fSs=)