The recent availability of multiplex nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATS) allows for the identification of M. genitalium, an increasingly important bacterium with rising antibiotic resistances.1–3 The authors present data with laboratory confirmation of M. genitalium infections within the first 3 years (from January 2019 to December 2021) when this test was already available in Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, Lisbon, Portugal. Patients were tested with a multiplex real-time PCR assay (Allpex™ STI Essential Assay Q MH and UU, Seegene, South Korea) which screens M. genitalium, Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis.

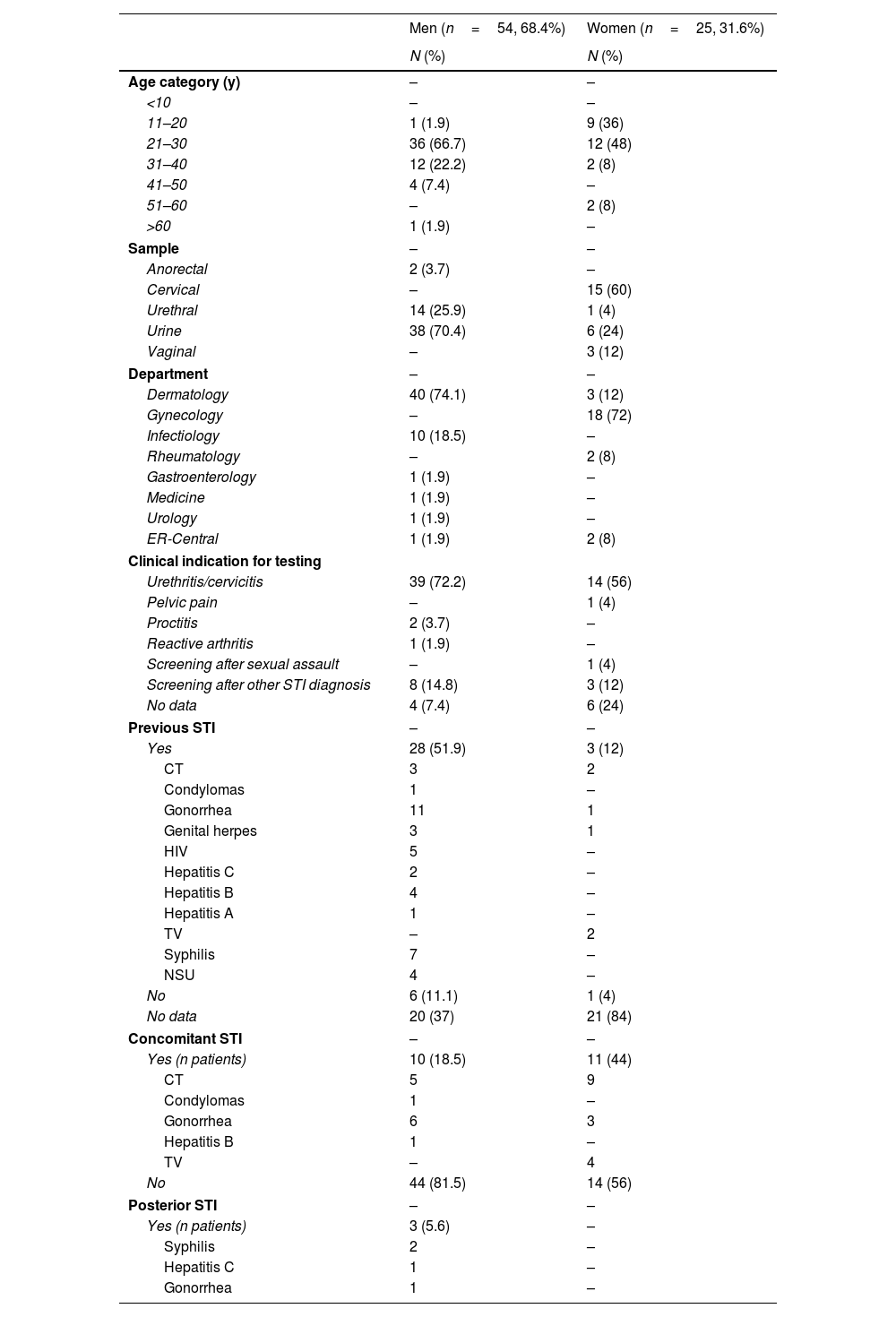

A total of 3206 samples were tested, resulting in 79 positive tests (corresponding to 78 patients) for M. genitalium (2.46%). Regarding the cases that tested positive, most were drawn from urine samples (n=45, 56.3%), followed by urethral and cervical swabs. The median age of participants was 27.5 years, and most were males (n=54, 68.4%). The most common indication for testing was urethritis and cervicitis (n=53, 67.9%), while there was no information available on the presence of symptoms in 10 patients. Most patients (64.3%) reported having heterosexual sex only, and 42.9% having 1 sexual partner in the past 6 months. Thirty-one (81.6%) out of the 38 patients with information available on their STI history, reported, at least 1 prior STI, and 13 (34.2%) 2 or more previous STIs. The most frequent previous diagnosis was gonorrhea (n=12, 31.6%). Concomitant STIs were present in 26.6% of the patients, including 8.9% with ≥2 concomitant STIs. If only women were considered, concomitant STIs were detected in 44%. The most frequent associations were chlamydia-induced genital infections (66.6%), and gonorrhea (38%). Four patients presented with ≥3 concomitant infections, and 6.3% of the patients were HIV-1 positive (Table 1).

Overview of the 78 patients included in the study regarding their age category, tested sample, department that made the diagnosis, and past, present, or posterior STIs.

| Men (n=54, 68.4%) | Women (n=25, 31.6%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age category (y) | – | – |

| <10 | – | – |

| 11–20 | 1 (1.9) | 9 (36) |

| 21–30 | 36 (66.7) | 12 (48) |

| 31–40 | 12 (22.2) | 2 (8) |

| 41–50 | 4 (7.4) | – |

| 51–60 | – | 2 (8) |

| >60 | 1 (1.9) | – |

| Sample | – | – |

| Anorectal | 2 (3.7) | – |

| Cervical | – | 15 (60) |

| Urethral | 14 (25.9) | 1 (4) |

| Urine | 38 (70.4) | 6 (24) |

| Vaginal | – | 3 (12) |

| Department | – | – |

| Dermatology | 40 (74.1) | 3 (12) |

| Gynecology | – | 18 (72) |

| Infectiology | 10 (18.5) | – |

| Rheumatology | – | 2 (8) |

| Gastroenterology | 1 (1.9) | – |

| Medicine | 1 (1.9) | – |

| Urology | 1 (1.9) | – |

| ER-Central | 1 (1.9) | 2 (8) |

| Clinical indication for testing | ||

| Urethritis/cervicitis | 39 (72.2) | 14 (56) |

| Pelvic pain | – | 1 (4) |

| Proctitis | 2 (3.7) | – |

| Reactive arthritis | 1 (1.9) | – |

| Screening after sexual assault | – | 1 (4) |

| Screening after other STI diagnosis | 8 (14.8) | 3 (12) |

| No data | 4 (7.4) | 6 (24) |

| Previous STI | – | – |

| Yes | 28 (51.9) | 3 (12) |

| CT | 3 | 2 |

| Condylomas | 1 | – |

| Gonorrhea | 11 | 1 |

| Genital herpes | 3 | 1 |

| HIV | 5 | – |

| Hepatitis C | 2 | – |

| Hepatitis B | 4 | – |

| Hepatitis A | 1 | – |

| TV | – | 2 |

| Syphilis | 7 | – |

| NSU | 4 | – |

| No | 6 (11.1) | 1 (4) |

| No data | 20 (37) | 21 (84) |

| Concomitant STI | – | – |

| Yes (n patients) | 10 (18.5) | 11 (44) |

| CT | 5 | 9 |

| Condylomas | 1 | – |

| Gonorrhea | 6 | 3 |

| Hepatitis B | 1 | – |

| TV | – | 4 |

| No | 44 (81.5) | 14 (56) |

| Posterior STI | – | – |

| Yes (n patients) | 3 (5.6) | – |

| Syphilis | 2 | – |

| Hepatitis C | 1 | – |

| Gonorrhea | 1 | – |

Note that in the previous, concomitant, and posterior STIs, the sum of all infections may be superior to the number in the “yes” row due to the presence multiple infections in some patients.

CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; HPV, human papillomavirus; MG, Mycoplasma genitalium; NG, Neisseria gonorrhea; NSU, non-specific urethritis; TV, Trichomomas vaginalis; y, years.

Concerning treatment, most patients (n=32, 40.5%) were treated before the microorganism identification, with a combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin, while 7 (8.9%) were treated with doxycycline. Due to failed empirical treatment, 5 patients (6.9%), were treated with a cycle of moxifloxacin, with complete symptom resolution and negative tests-of-cure 3 weeks after treatment completion. No treatment data was available for 46.8% of the patients. Almost half (48.8%) of the 43 confirmed cases of M. genitalium referred to the outpatient clinic of STIs, did not go to their appointment.

M. genitalium is an emerging microbe, with cumulative evidence for its role in non-gonococcal urethritis in men, and cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, preterm birth, and spontaneous abortions in women.2,4 Concomitant infections may act as confounding factors in understanding the percentage of symptomatic and asymptomatic M. genitalium infections. Most patients are treated empirically before organism identification. Ideally, after identification, antibiotic resistance testing should guide therapy. When macrolide resistance testing is not available, as it is the case with our center, the recommended regimen is a 100mg-course of doxycycline orally 2times/day for 7 days, which reduces the organism load and facilitates organism clearance, followed by moxifloxacin 400mg orally once a day for 7 days. An alternative regimen includes the substitution of moxifloxacin for azithromycin (1g orally on day 1+500mg once a day for 3 days) plus a test-of-cure 21 days after treatment completion.5

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, the inclusion of patients from multiple departments and, therefore, its heterogenous clinical context, and low percentage of complete clinical diaries (e.g., regarding sexual orientation). We should mention that screening and treatment of asymptomatic or extragenital M. genitalium infection is ill-advised.5,6 In our series, information on the presence of symptoms was not available in 10 patients. We should mention the high prevalence of M. genitalium infection in young adults, the frequency of previous STIs and co-infections, and the high percentage of patients lost to follow-up. The latter may halt the treatment of sexual contacts and overall patient management, including risk discussion, lab confirmation of cure, and referral to other departments (e.g., PrEP appointments).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.