Solar urticaria (SU) is characterized by an immediate onset of erythema and itchy wheals within 5–10min of exposure to solar radiation, which disappear in a few hours.1,2 Very uncommon isolated cases of delayed-onset SU have been described, in which the lesions appear several hours after sun exposure and may last up to 24h.3–7

Case reportA 58-year-old woman, with a personal history of asthma and allergic rhinitis, was referred to our dermatology department due to the appearance of delayed outbreaks of itchy wheals in photoexposed areas throughout the previous 8 years. The lesions appeared within 2–3h after sun exposure and faded after 24–48h. In addition, by the same time, she also had spontaneous outbreaks of wheals in any location unrelated to any activity or triggering physical factors. As previous treatments, she had undergone UVB narrowband phototherapy (34 sessions with a total dose of 17.15J/cm2) in other hospital, with frequent outbreaks of lesions that appeared 5h after treatment without achieving skin hardening.

Complementary tests included a general blood test with tryptase and autoimmunity that showed no alterations. Total IgE was 210UI/ml. Skin prick test was positive for 4 lines.

The patient had no relevant dermatological history, and denied consuming or using any medicines prior to the episodes. Her Fitzpatrick phototype was II and no lesions were present at the time of the consultation.

Exposure to solar light (face, neck, cleavage area and back of forearms) at 12.00 a.m. induced no lesions after 20min. Two hours after photo-exposure, asymptomatic erythematous lesions appeared in the cleavage area and disappeared in 3–4h.

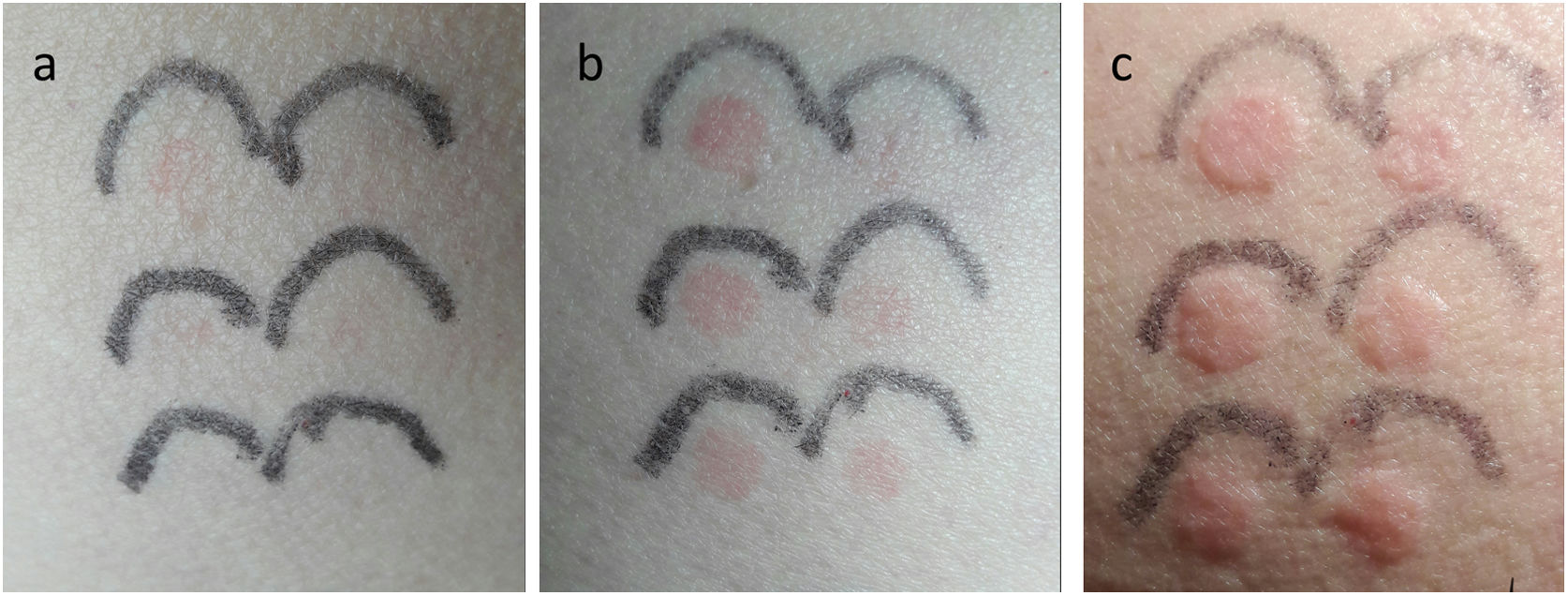

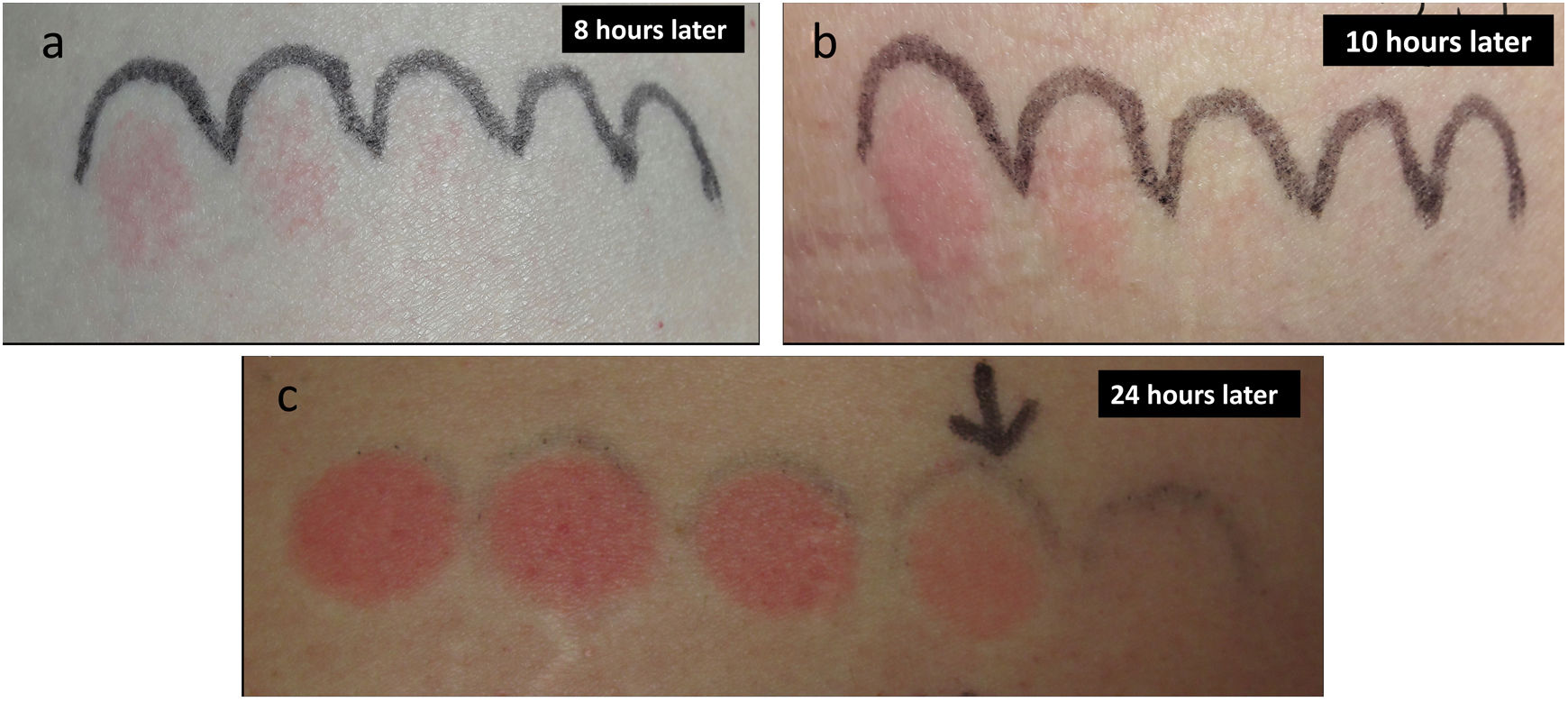

Phototest/photoprovocation using a UVB+UVA solar simulator (SS) (6 spot doses of 45.01, 33.31, 24.66, 18.25, 13, 51 and 10mJ/cm2; Multiport 601, Solar Light Co®, USA) broad-band UVA (5 spot series up to 8.9J/cm2; Gigatest, Medisun® 2008, Germany), broad-band UVB (5 spot series of 67, 56, 40, 22 and 5mJ/cm2; Gigatest, Medisun® 2008, Germany); and visible light (VL) (slide projector located 10cm away, with 8×8cm spot area, on the left dorsal area, for 30min) were all negative at immediate reading. However, 12h after the phototest was performed, the patient reported and self-photographed the appearance of wheals in the 6 spots exposed to the SS (Fig. 1).

Delayed response to SS exposure: (a) 6h, (b) 8h and (c) 10h after stimulation. Images show the appearance of wheals that disappeared after 24h. Irradiation doses with SS were (from upper left to lower left and then from lower left to upper right): 45.01, 33.31, 24.66, 18.25, 13, 51 and 10mJ/cm2.

In the 24-h reading, all wheals had disappeared and the minimal erythema dose (MED) was considered to be normal for her phototype (MED: 22mJ/cm2) (Fig. 2).

Several months later, the patient complained of an intense outbreak of itchy erythematous papules on the cleavage, arms and legs, which persisted for several days. The patient reported that she had similar lesions in previous summers. The lesions were considered to be clinically consistent with polymorphic light eruption (PLE). Further photoprovocation of PLE was not performed.

The patient was treated with seven doses of omalizumab 300mg s.c. every 4 weeks together with bilastine 20mg daily and progressive heliotherapy reaching total control of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and the pruritus within two weeks as well as improvement of sun tolerance.

DiscussionDelayed-onset SU is very rarely described in the medical literature.3–7 Wheals are elicited by high dose of UVA,3,5 low doses of UVA or UVB4,6 or only by UVB,7 as is the case in our patient. This fact suggests that delayed-onset SU is very rare and it is due in all cases to a spectrum of UV effects rather than to VL, unlike the non-delayed SU series reported in the literature.1,2,7–9 Co-occurrence of PLE and SU was reported to be as high as 23% in one case series of 87 patients,8 whereas PLE has only been reported in coexistence with delayed-onset SU in one case,7 as in our case. Lastly, only Ghigliotti et al. reported coexistence of CSU with delayed-onset SU in one patient.5

To conclude, we would like to point out that, in addition to CSU, SU can be also associated with other inducible chronic urticaria, making its diagnosis difficult. Although the association with other photodermatoses has been described, photobiological studies should be carried out in the cases in which a delayed form of SU overlaps with PLE.

Although delayed SU is very rare, it must be clinically considered in order to correctly perform and interpret photoprovocation tests. In our case, the patient collaboration was essential to assess the skin responses several hours later.

We present the first case of delayed-onset SU induced by UVB radiation, associated with PLE and CSU. The potential relationship between delayed-onset SU, PLE and CSU is unclear and should be investigated in the future.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.