A 52-year-old man with hypertension managed by dietary intervention, reported having itchy papular and vesicular lesions for 3 years. The intensity of these lesions varied but they had always been present on the forearms, and to a lesser extent on the cervicofacial region, abdomen, and legs. He received antihistamine treatment and prednisone (15 mg/d) without any improvement. He did not have any personal or family history of atopy. He worked in a factory handling car chassis parts with no clear improvement during vacations.

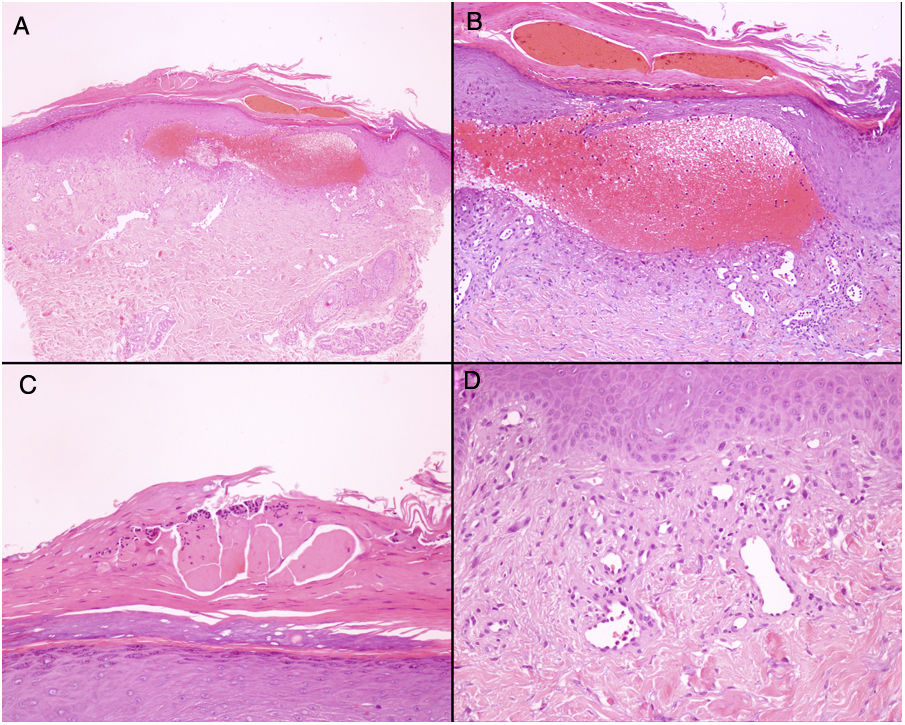

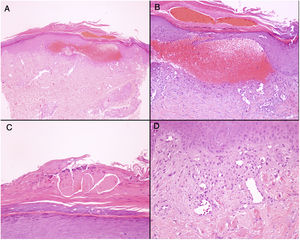

Physical ExaminationSkin examination showed the presence of extensive excoriation on an erythematous base. The lesions formed extensive chaffed plaques of eczematous appearance on the forearms, cervicofacial region, abdomen, and legs (Fig. 1). Skin biopsy samples from the lesions were taken. Adhesive tape stripping was performed, and the sample subsequently placed on a microscope slide for viewing under an optical microscope.

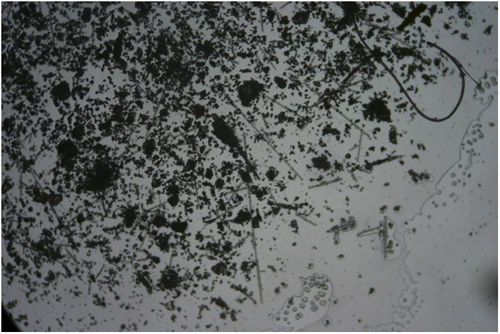

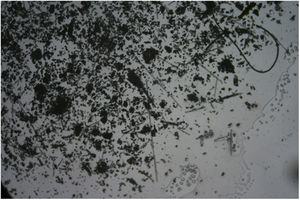

Additional TestsThe blood tests, which included IgE, did not show any significant abnormalities. Skin patch tests were performed with the standard battery of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group, with negative results. Biopsy showed the presence of a subepidermal hemorrhagic blister and hyperkeratosis with acanthosis, consistent with a lesion caused by scratching (Fig. 2). In the sample obtained by adhesive tape stripping, several linear fragments could be seen with a variable diameter under the microscope with polarized light, consistent with glass fibers (Fig. 3). [[?]]What was the diagnosis?

Fiberglass dermatitis (FGD)

Course and TreatmentThe patient confirmed close contact with fiberglass materials when handling chassis parts. He was recommended to use protective clothing when at work and was prescribed topical treatment with betamethasone and gentamycin, along with oral antihistamine agents. Given a suboptimal control of the clinical symptoms, the patient took several months sick leave, with substantial and sustained improvement in his condition. He finally obtained occupational disability, and remained completely asymptomatic.

CommentFiberglass is a widely used material in construction, although given its thermal, acoustic, and electrical insultation properties, it is also used outside that sector. Fiberglass is a clinically inert material that in itself does not lead to sensitization but this may sometimes occur because of resins and other additives used in the final fiberglass product, giving rise to cases of contact allergic eczema.1 Nevertheless, fiberglass dermatitis, first described in 1942 by Sulzberger and Baer,2 is an irritative contact dermatitis considered a frequent cause of occupational dermatitis. The pathogenic mechanism consists of penetration of glass fragments into the stratum corneum, leading to mechanical irritation.3 Although less frequently described, an airborne transportation mechanism is also possible.4 From the clinical point of view, presentation is in the form of chaffing caused by uncontrolled itching, which may ultimately resemble prurigo, within a broad spectrum of eczematous lesions. Of note is that the intensity of irritation is proportional to the diameter of the fragments, and inversely proportional to their length. Medical history is essential to identify exposure to glass fiber, and so it is important that dermatologists are aware of the existence of this disease. A further barrier to recognition of the condition is that prolonged exposure generates tolerance to the fiber, whereas patients with shorter durations of exposure are those who develop lesions.5 Contact tests are not useful for diagnosis, for the reasons highlighted above, although they may be of relevance for identifying concomitant sensitization to additives. Although histopathological study is of little use, as illustrated by our case, it could eventually identify birefringent fiberglass fragments embedded in the stratum corneum.3 A simple and noninvasive test is to obtain a skin sample from the area of the lesion using an adhesive strip. Fiberglass fragments can be observed among corneal remnants under an electron microscope,6 thus providing a definitive diagnosis.

Please cite this article as: Company-Quiroga J, Córdoba A, Borbujo J. Excoriaciones diseminadas de larga evolución. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:511–512.