Annular lichenoid dermatitis of youth is a lichenoid dermatosis of unknown etiology. It mostly affects children and adolescents and has well-defined clinical and histological characteristics that permit a diagnosis. We present 2 new cases of annular lichenoid dermatitis of youth with classical clinical features in 2 girls, aged 2 and 4 years. The histologic findings, however, differed from those reported in the literature in that the lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate was located primarily at the top of the dermal papillae and not at the tips of the rete ridges. In both cases, the lesions regressed spontaneously without treatment.

La dermatitis anular liquenoide de la infancia es una entidad de etiología desconocida que forma parte del grupo de las dermatosis liquenoides. Afecta sobre todo a niños y adolescentes, mostrando unas características clinicopatológicas definidas que permiten su diagnóstico. Presentamos 2 nuevos casos de dermatitis liquenoide anular de la infancia en 2 niñas de 4 y 2 años y medio, respectivamente, que presentan las características clínicas clásicas de esta entidad. A diferencia del resto de casos publicados el examen histopatológico mostró un infiltrado inflamatorio liquenoide situado principalmente en el techo de las papilas dérmicas, y no en la punta de las crestas epidérmicas. En ambos casos las lesiones regresaron espontáneamente sin necesidad de tratamiento.

Annular lichenoid dermatitis of youth (ALDY) is an uncommon clinical and histopathological condition of unknown etiology and pathogenesis. Clinically, it is characterized by annular erythematous lesions with a whitish center located on the trunk; histologically, it is characterized by a lichenoid infiltrate with necrotic keratinocytes, found generally at the tip of the rete ridges. We present 2 new cases of this disease and review the literature to date.

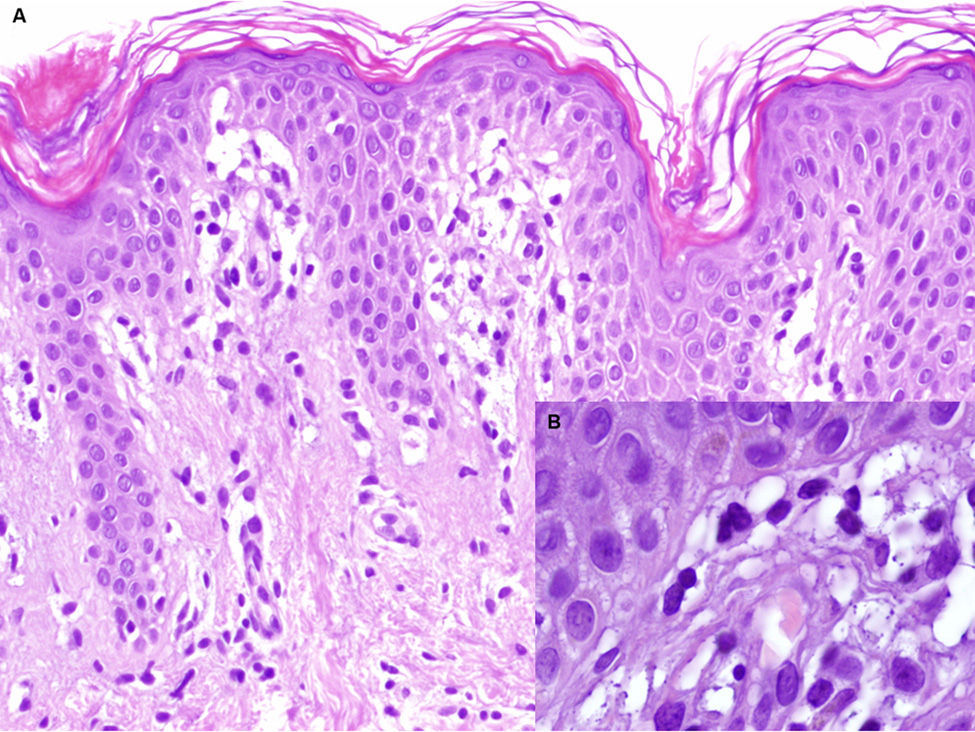

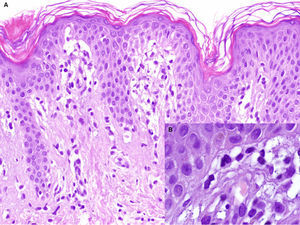

Patient 1A healthy 4-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of asymptomatic lesions on both flanks and groins and on her left axilla. The physical examination revealed well-defined annular plaques with a slightly palpable erythematous edge and hypopigmented center (Fig. 1). Analysis of a biopsy specimen from the edge of the lesion revealed elongated and quadrangular rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal layer, and a lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2 A and B). Immunohistochemistry revealed a predominance of CD3+ and CD4+ lymphocytes. No further tests were performed, and the patient was prescribed emollient creams. Five months later, the lesions returned spontaneously. No further relapses have been recorded after 2 years of follow-up.

A. Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification,×100. Biopsy of the edge of the lesion. Elongated rete ridges with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate at the top of the dermal papillae and vacuolization of the basal layer. B. Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification,×400. Greater detail showing multiple apoptotic keratinocytes.

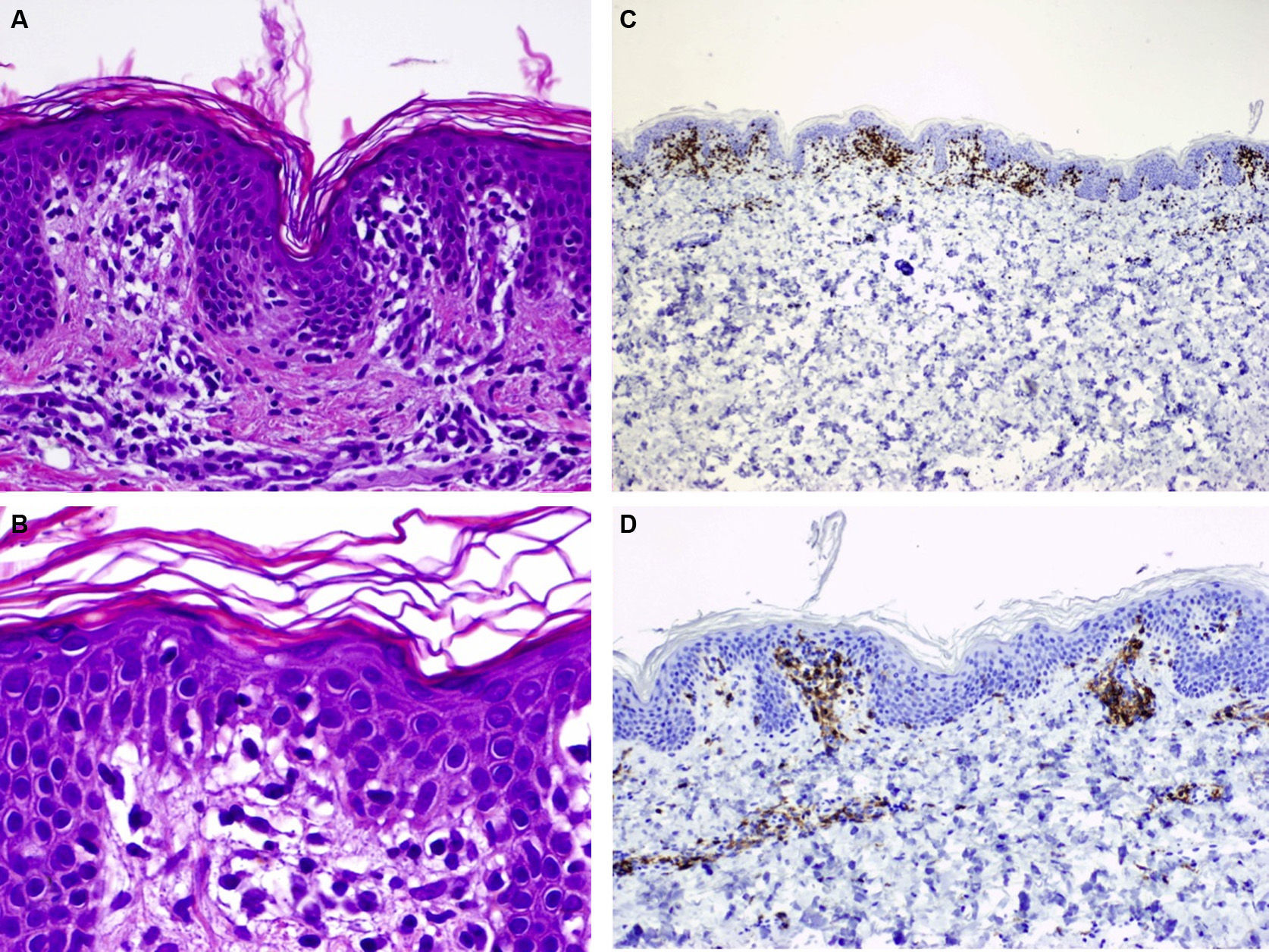

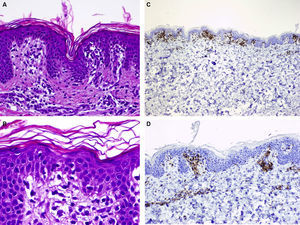

A healthy girl aged 2.5 years presented with a 3-month history of asymptomatic lesions on the left side of the abdomen and suprapubic region. The lesions took the form of annular plaques measuring 6 and 1.5cm, respectively, with a slightly palpable erythematous edge and a hypopigmented center (Fig. 3). Histopathology of the edge of one of the lesions revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, edema of the papillary dermis, and an lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate located mainly at the top of the dermal papillae (Fig. 4A and B). Immunohistochemistry revealed a predominance of CD3+ and CD4+ lymphocytes (Fig. 4C and D). The lesions regressed without treatment at 7 months. No relapses have been recorded after 3 years of follow-up.

A, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification,×100. Biopsy of the edge of one of the lesions showing basket weave hyperkeratosis, edema in the papillary dermis, and a lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate located mainly at the top of the dermal papillae. B, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification,×200. Greater magnification reveals edema in the papillary dermis and lymphocytes in the dermal papillae. C, Immunohistochemistry reveals an infiltrate formed by CD3+ lymphocytes (×40). D, CD4+ lymphocytes (×100).

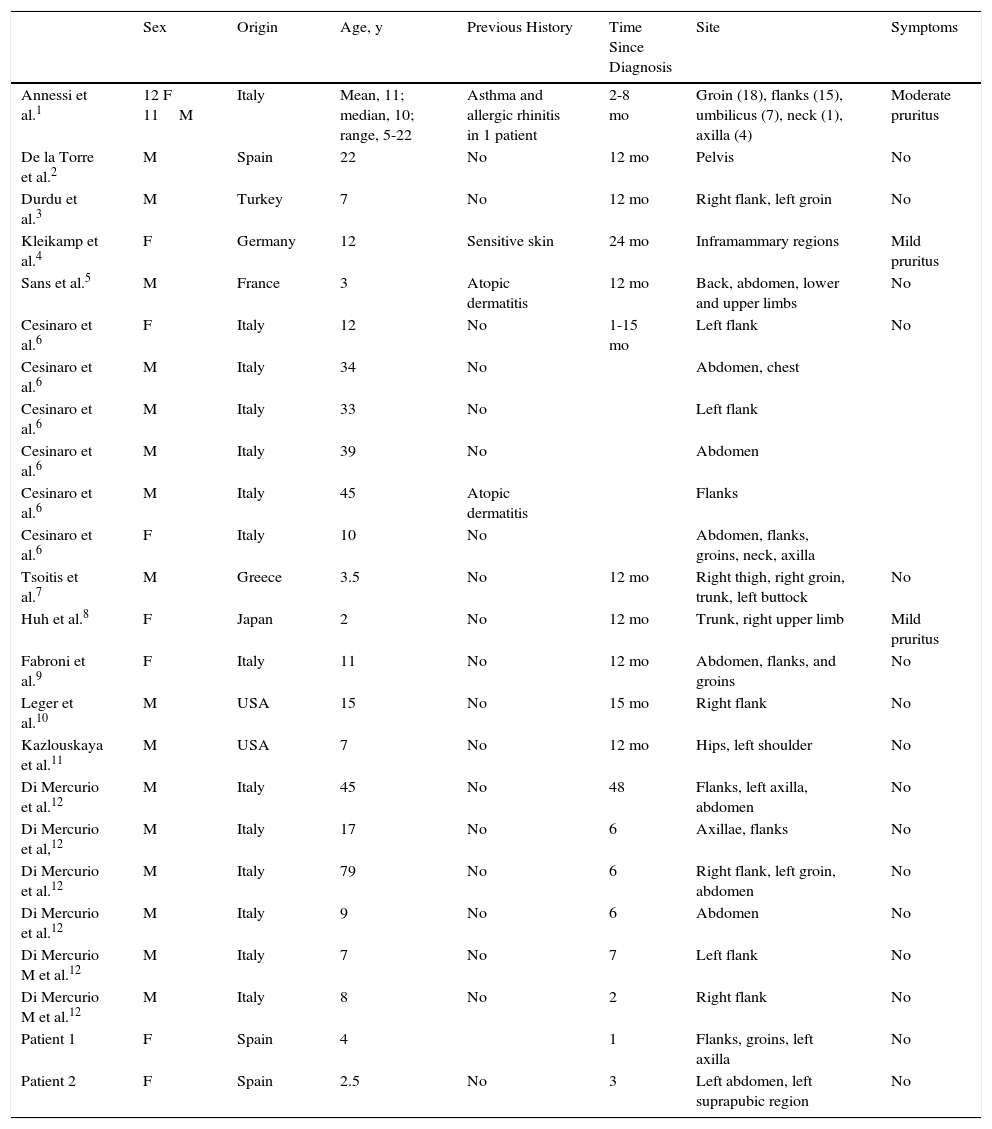

ALDY forms part of a wide group of lichenoid skin diseases. It was first reported in 2003,1 and since then 46 cases have been published (Table 1).1–12 Given its clinical and histopathological similarity to other skin diseases, especially mycosis fungoides, it is probably underdiagnosed, potentially leading to erroneous diagnosis and management.

Clinical and Epidemiological Data for Published Cases of Annular Lichenoid Dermatitis of Youth.

| Sex | Origin | Age, y | Previous History | Time Since Diagnosis | Site | Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annessi et al.1 | 12 F 11M | Italy | Mean, 11; median, 10; range, 5-22 | Asthma and allergic rhinitis in 1 patient | 2-8 mo | Groin (18), flanks (15), umbilicus (7), neck (1), axilla (4) | Moderate pruritus |

| De la Torre et al.2 | M | Spain | 22 | No | 12 mo | Pelvis | No |

| Durdu et al.3 | M | Turkey | 7 | No | 12 mo | Right flank, left groin | No |

| Kleikamp et al.4 | F | Germany | 12 | Sensitive skin | 24 mo | Inframammary regions | Mild pruritus |

| Sans et al.5 | M | France | 3 | Atopic dermatitis | 12 mo | Back, abdomen, lower and upper limbs | No |

| Cesinaro et al.6 | F | Italy | 12 | No | 1-15 mo | Left flank | No |

| Cesinaro et al.6 | M | Italy | 34 | No | Abdomen, chest | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | M | Italy | 33 | No | Left flank | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | M | Italy | 39 | No | Abdomen | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | M | Italy | 45 | Atopic dermatitis | Flanks | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | F | Italy | 10 | No | Abdomen, flanks, groins, neck, axilla | ||

| Tsoitis et al.7 | M | Greece | 3.5 | No | 12 mo | Right thigh, right groin, trunk, left buttock | No |

| Huh et al.8 | F | Japan | 2 | No | 12 mo | Trunk, right upper limb | Mild pruritus |

| Fabroni et al.9 | F | Italy | 11 | No | 12 mo | Abdomen, flanks, and groins | No |

| Leger et al.10 | M | USA | 15 | No | 15 mo | Right flank | No |

| Kazlouskaya et al.11 | M | USA | 7 | No | 12 mo | Hips, left shoulder | No |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | M | Italy | 45 | No | 48 | Flanks, left axilla, abdomen | No |

| Di Mercurio et al,12 | M | Italy | 17 | No | 6 | Axillae, flanks | No |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | M | Italy | 79 | No | 6 | Right flank, left groin, abdomen | No |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | M | Italy | 9 | No | 6 | Abdomen | No |

| Di Mercurio M et al.12 | M | Italy | 7 | No | 7 | Left flank | No |

| Di Mercurio M et al.12 | M | Italy | 8 | No | 2 | Right flank | No |

| Patient 1 | F | Spain | 4 | 1 | Flanks, groins, left axilla | No | |

| Patient 2 | F | Spain | 2.5 | No | 3 | Left abdomen, left suprapubic region | No |

| Serology Borrelia | Biopsy | Rearrangement | Treatment | Remission | Recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annessi et al.1 | Negative (23) | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, elongated rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal layer, necrotic keratinocytes at the tip of the epidermal ridges | Polyclonal (15 patients) | 1) Topical CCs (17); 2) PRD po 1mg/kg/d× 4 wk (1); 3) UV-A1 (60J/cm2) (1); 4) PUVA (1); 5) heliotherapy (3); 6) other: eosin 2%, topical and oral antibiotics | 1) Partial or complete; 2) Complete; 3) Complete; 4) Complete; 5) Partial; 6) No response | Chronic course in all patients, multiple recurrences |

| De la Torre et al.2 | Negative | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, apoptosis at the tip of the rete ridges | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Partial | Yes |

| Durdu et al.3 | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis, vacuolization of the basal layer, apoptotic keratinocytes, epidermal exocytosis | Topical CCs | Partial | Yes | ||

| Kleikamp et al.4 | Negative | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes at the tip of the rete ridges | Polyclonal | 0.03% tacrolimus | Complete | No |

| Sans et al.5 | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate in the papillary dermis, necrotic keratinocytes at the tip of the rete ridges | Topical CCs | No | Increased no. of lesions | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | CD8+ lichenoid infiltrate, cluster of lymphocytes at the tip of the rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal layer, elongated and quadrangular rete ridges | Polyclonal | No | Spontaneous regression | ||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | Topical CCs | No | Spontaneous regression | |||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | Topical CCs | No | Spontaneous regression | |||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | No | |||||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | Topical tacrolimus | No | Spontaneous regression | |||

| Cesinaro et al.6 | No | |||||

| Tsoitis et al.7 | Negative | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate in the papillary dermis with occasional MGCs, vacuolization of the basal layer, edema and colloid bodies in the papillary dermis | No | Spontaneous regression of some lesions | ||

| Huh et al.8 | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, vacuolization of the basal layer, elongated rete ridges, colloid bodies in the stratum spinosum and papillary dermis | Topical CCs | Partial | Persistence | ||

| Fabroni et al.9 | CD8+ lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate affecting the dermal-epidermal junction, mild hyperkeratosis | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Complete | No | |

| Leger et al.10 | Negative | CD4+ lichenoid infiltrate, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, quadrangular rete ridges, necrotic keratinocytes at the top of the rete ridges | Polyclonal | 1) Intralesional and systemic CCs; 2) Doxycycline (3 wk) | 1) Complete 2) No | Yes |

| Kazlouskaya et al.11 | CD8+ lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate affecting the tip of the rete ridges, apoptotic keratinocytes, foci of epidermotropism with occasional cerebriform nuclei | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Complete | No | |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | Negative | CD4+ lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary dermis, elongated and quadrangular rete ridges, apoptosis of keratinocytes at the tip of the rete ridges | Polyclonal | Phototherapy, topical CCs | Partial | Yes |

| Di Mercurio et al,12 | Negative | Polyclonal | Topical CCs, 0.1% tacrolimus | Complete | No | |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | Negative | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Complete | No | |

| Di Mercurio et al.12 | Negative | Polyclonal | Topical CCs, 0.1% tacrolimus | Complete | No | |

| Di Mercurio M et al.12 | Negative | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Complete | No | |

| Di Mercurio M et al.12 | Negative | Polyclonal | Topical CCs | Complete | No | |

| Patient 1 | CD4+ lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate, vacuolization of the basal layer at the top of the dermal papillae | No | Spontaneous regression | |||

| Patient 2 | CD4+ lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary dermis, basket weave hyperkeratosis, foci of spongiosis, edema in the papillary dermis | No | Spontaneous regression |

Abbreviations: CC, corticosteroid; MGC, multinucleated giant cell; F, female; M, male; PRD, prednisolone; PUVA, psoralen UV-A.

ALDY mainly affects young people (mean age, 14.7 years; median age, 10.5 years [range, 2-79 years]), although it has also been reported in adults; therefore, it has been suggested that the name of the disease be changed to annular lichenoid dermatitis. The disease affects slightly more males than females (27M/19F), mainly white persons of European origin, especially from the Mediterranean area,1–7,9,12 although the disease has been reported in 2 American males10,11 and a Japanese girl.8

Patients with ALDY do not have a relevant history, except for 2 patients who had atopic dermatitis5,6 and a patient with asthma and allergic rhinitis.1

Clinically, ALDY is characterized by the presence of 1 or more well-defined erythematous macules that grow slowly at the periphery to form larger annular plaques. The plaques usually have a slightly raised erythematous edge and hypopigmented center. The peripheral erythema becomes paler with time, leading to annular or arcuate brownish hyperpigmentation. In some cases, small lichenoid papules are visible at the periphery of the lesions.4,11 These lesions are located mainly on the trunk, especially the flanks and abdomen, with characteristic ptychotropism, ie, affinity for skin folds (groin, umbilicus, neck, and axillae). The lesions are usually asymptomatic, although mild to moderate pruritus has been reported.1,4,8

Histopathology findings depend on the time since diagnosis of the lesion. Early lesions are characterized by a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis and vacuolar degeneration at the dermal-epidermal junction. The infiltrate has been reported mainly at the tip of the rete ridges and causes necrosis of keratinocytes. However, the cases we report differ from other published cases1–12 in that the infiltrate mainly affected the top of the dermal papillae. Late lesions present as clusters of apoptotic keratinocytes that are sometimes located in the papillary dermis.7,8 The papillary dermis shows disperse lymphocytic infiltrates with the presence of melanophages. In some cases, fibroplasia has been reported in the papillary dermis and seems to be associated with the chronic nature of the lesions.11

Immunohistochemistry reveals disparate results. In most cases, including those we report here, there is an infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+/CD45RO+ lymphocytes.1–5,7,8,10,12 However, a predominance of CD8+ and TA1+ lymphocytes has been reported.6,9,11

A molecular workup carried out in 27 patients revealed polyclonal rearrangement in all 27, in contrast with the monoclonal lymphoid proliferation observed in 52%-75% of cases of mycosis fungoides.13 Therefore, in cases of uncertain diagnosis, it would seem appropriate to investigate clonal T-cell receptor γ gene rearrangements, since, even though the absence of monoclonal rearrangement does not rule out mycosis fungoides, it does constitute a factor that favors ALDY.

The precise etiology and pathogenesis of ALDY are unknown, although immunohistochemistry findings suggest that the condition could be caused by a cytotoxic T cell–mediated immune reaction, as is the case in other lichenoid skin diseases. The absence of signs of infection and the lack of a response to antibiotics rule out its association with an infectious disease process. Serology testing for Borrelia burgdorferi was negative in 33 cases, as was serology testing for parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus.4–12 Sans et al.5 reported an association between ALDY and hepatitis B vaccine; however, no such association was recorded in the remaining published cases. Similarly, no association was found with drugs, autoimmune disease, or neoplasm. The results of patch testing have also been shown to be negative.1,2

The differential diagnosis should be based mainly on mycosis fungoides, inflammatory morphea, vitiligo, and annular erythema (annular erythema of infancy and erythema annulare centrifugum).

ALDY can be considered to mimic mycosis fungoides, the lesions of which usually have a partially desquamative and velvety surface. Furthermore, the presence of erythematous or brownish edges makes it possible to distinguish between ALDY and the hypopigmented form of mycosis fungoides seen during childhood.14 A series of histopathological criteria seem to point to ALDY, as follows: (1) elongated and quadrangular rete ridges; (2) absence of parakeratosis; (3) presence of intraepidermal lymphocytes and necrotic keratinocytes at the tips of the rete ridges; (4) absence of epidermotropism and of atypical lymphocytes; (5) absence of fibrosis in the papillary dermis (present in up to 97% of early mycosis fungoides lesions).1,6,11,15

Inflammatory morphea can manifest as asymptomatic oval plaques with a whitish center and reddish-violet edges. However, the lesions usually present as an induration with a shiny and atrophic surface and no lichenoid infiltrate. However, where morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus overlap, we can find both sclerosis and a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate, which hinder the differential diagnosis.11

We can also observe a lichenoid infiltrate in inflammatory vitiligo, although the epidermis is usually flattened in comparison with the hyperplastic epidermis in ALDY. Furthermore, the presence of a normal melanocyte count in the hypopigmented areas and the rapid and homogeneous repigmentation observed after topical treatment make it possible to differentiate ALDY from vitiligo.11

The course of ALDY tends to be chronic, with frequent recurrences. Cases of spontaneous resolution, such as those described here, have been reported.6,7 The response to treatment has proven to be very variable. In some cases, topical corticosteroids and 0.03% tacrolimus ointment resolved the lesions completely, with no subsequent recurrence.4,11,12 However, in other cases, the authors only recorded variable responses with recurrence after suspension of therapy. Other treatments used include phototherapy (UV-A), photochemotherapy (psoralen-UV-A), systemic antibiotics (doxycycline,10 macrolides, and cephalosporins), topical antibiotics (gentamicin and mupirocin), and eosin 2%.1,12

ConclusionALDY is a lichenoid skin condition that is found in early stages of life. Its well-defined clinical and pathological characteristics facilitate diagnosis. Despite the excellent prognosis of ALDY, its clinical and histopathologic similarity to mycosis fungoides highlights the need for periodic follow-up.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Osorio I, González-Sabín M, Gonzalvo-Rodríguez P, Rodríguez-Díaz E. Dermatitis anular liquenoide de la infancia. Descripción de 2 casos y revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:e39–e45.